V. THE CRUSADES (cont.)

V. THE CRUSADES (cont.) V. THE CRUSADES (cont.)

V. THE CRUSADES (cont.)The history of the Children's Crusade has been shrouded in mysterious silence, probably for a variety of reasons: in part, because the participants were mostly children with little or no education and of the lower social strata, and were thus unable to readily commit their experiences in writing; in part, because nearly two decades passed before anyone knew what had happened to many of them; in part, because the Children's Crusade is a conundrum, that is, something difficult to fully understand and explain without challenging our notions of "acceptable" conduct; and in part, because many of the chroniclers of the day would have had to stare straight into the face of their own "mea culpa," for their own failure to answer the call of Christ's Vicar on earth. Nevertheless, the sheer numbers of the participants and the incredible sacrifices made by them, cries out for their story to be told. Even though the historical evidence regarding this crusade is scant, below is believed to be an accurate account, based upon the best of this evidence.

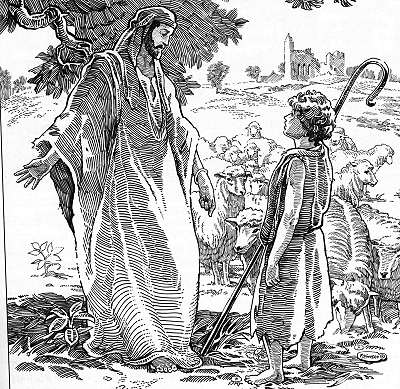

One

day in May 1212 there appeared at Saint-Denis, where King Philip of France was holding his

court, a shepherd-boy of about twelve years old called Stephen, from the small town of

Cloyes in France. We know little about him except that he was tall, thin, with bright blue

eyes and bushy brown hair. He walked barefoot and dressed in rags. He was an orphan whose

parents died in an epidemic when Stephen was about 5 years old.

One

day in May 1212 there appeared at Saint-Denis, where King Philip of France was holding his

court, a shepherd-boy of about twelve years old called Stephen, from the small town of

Cloyes in France. We know little about him except that he was tall, thin, with bright blue

eyes and bushy brown hair. He walked barefoot and dressed in rags. He was an orphan whose

parents died in an epidemic when Stephen was about 5 years old.

During the epidemics and plagues of the Middle Ages there were thousands of orphan children who had no place to go and no one to care for them. Some were taken in by the monasteries; some, like Stephen, worked as shepherds or farmhands in exchange for their meals and a place to sleep. But many of the children wandered around, begging, stealing, sleeping in fields, and dying of hunger and disease.

Stephen brought with him a letter for the King, which, he said, had been given to him by Christ in person, Who had appeared to him as he was tending his sheep and Who had bidden him go and preach the Crusade. King Philip was not impressed by the child and told him to go home.

Fifteen

years earlier the Muslims had recaptured Jerusalem and were pressing the Christians armies

against the Palestine coast. Pope Innocent III, fearing disaster, had sounded the alarm by

calling upon the knights of Europe to rescue their brethren and save the Holy Land; but

His call fell mainly on deaf ears. Against this backdrop, Stephen, whose enthusiasm had

been fired by his mysterious visitor, saw himself now as an inspired leader who would

succeed where his elders had failed.

Fifteen

years earlier the Muslims had recaptured Jerusalem and were pressing the Christians armies

against the Palestine coast. Pope Innocent III, fearing disaster, had sounded the alarm by

calling upon the knights of Europe to rescue their brethren and save the Holy Land; but

His call fell mainly on deaf ears. Against this backdrop, Stephen, whose enthusiasm had

been fired by his mysterious visitor, saw himself now as an inspired leader who would

succeed where his elders had failed.

It was easy for a boy to be infected with the idea that he too could be a preacher and could emulate the renowned preacher of the First Crusade, Peter the Hermit, whose prowess had during the past century reached a legendary grandeur. Undismayed by the King's indifference, he began to preach at the very entrance to the abbey of Saint-Denis and to announce that he would lead a band of children to the rescue of Christendom. He likened Jesus to a banished king, Jerusalem to a captive queen. He proclaimed that the seas would dry up before them, and they would pass, like Moses through the Red Sea, safe to the Holy Land. He was gifted with an extraordinary eloquence. Older folk were impressed, and children came flocking to his call. After his first success, he set out to journey around France summoning the children; and many of his converts went further afield to work on his behalf. They were all to meet together at Vendôme in about a month's time and start out from there to the East. Some parents refused to allow their children to join the crusade, but this did not always stop the young ones. One writer wrote: "The children left their mothers and fathers, their nurses and all their friends, singing just like Stephen. Bolted doors could not keep them in, nor could their parents call them back."

The extraordinary devotion of these children brings a stunned pause to those of lesser commitment. But not to be forgotten is the incredible sacrifice of the majority of the parents who released their beloved children with both blessing and tears. Their offering must have been tortuous and the excruciating pain of surrendering a child to the mysteries and dangers of this kind of pilgrimage can hardly be imagined.

So by June these unsuspecting lambs of Europe began to gather in flocks to begin their

"pilgrimage" southward; for crusades were often viewed as a special type of

pilgrimage rather than a military exercise (which would help explain the lack of weaponry

and finance that characterized this crusade). In an environment where good works were

believed to earn eternal salvation and earthly blessing, these children rallied in sincere

submission to a God whose Hands they gladly placed their trust. Many prepared to march

without provisions so that their faith might be proven pure and their utter dependency on

an all-powerful God proven.

So by June these unsuspecting lambs of Europe began to gather in flocks to begin their

"pilgrimage" southward; for crusades were often viewed as a special type of

pilgrimage rather than a military exercise (which would help explain the lack of weaponry

and finance that characterized this crusade). In an environment where good works were

believed to earn eternal salvation and earthly blessing, these children rallied in sincere

submission to a God whose Hands they gladly placed their trust. Many prepared to march

without provisions so that their faith might be proven pure and their utter dependency on

an all-powerful God proven.

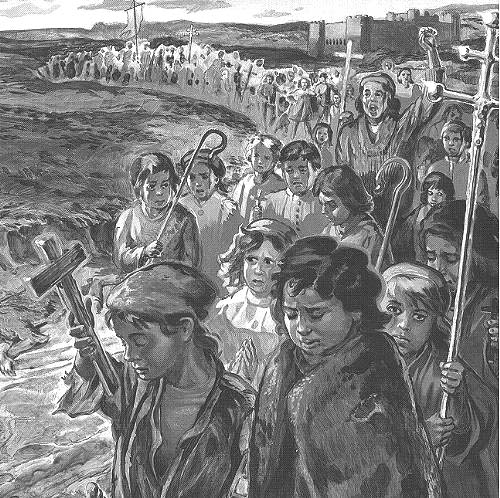

Towards the end of June the children massed at Vendôme. Awed contemporaries spoke of thirty thousand, not one over twelve years of age. There were certainly many thousands of them, collected from all parts of the country, some of them simple peasants, whose parents in many cases had willingly let them go on their great mission. But there were also boys of noble birth who had slipped away from home to join Stephen and his following of "minor prophets" as the chroniclers called them. There were also girls amongst them, a few young priests, some monks and nuns, and a few older pilgrims, some drawn by piety, others, perhaps, from pity, and others, certainly, to share in the gifts that were showered upon them all. The bands came crowding into the town, but the town could not contain them all, and they encamped in the fields outside.

When the blessing of friendly priests had been given, and when the last sorrowing parents had given leave, the expedition started out southward. Nearly all of them went on foot and looked quite different from the seasoned veterans who had marched in the previous crusades. Instead, this eager army of Christendom was an assembly of bold adolescents and spirited boys and girls holding waxed tapers and waving perfumed censers. And if asked how they would accomplish what grown men could not, they replied that they were equal to the will of God and whatever He might wish for them, that they would humbly and gladly accept.

Stephen, as he thought befitted the leader, insisted on having a gaily-decorated cart for himself, with a canopy to shade him from the sun. At his side rode boys of noble birth, each rich enough to possess a horse. No one resented the inspired prophet travelling in comfort. On the contrary, he was treated as a saint, and locks of his hair and pieces of his garments were collected as precious relics. They took the road past Tours and Lyons, making for Marseilles. It was a painful journey. The summer was unusually hot. They depended on charity for their food, and although most people were happy to help such a holy cause, the drought left little to spare in the country, and water was scarce. Many of the children died by the wayside. Others dropped out and tried to wander home. By the time the little Crusade reached Marseilles, their numbers had been reduced from 30,000 to 7,000 children, by one estimate!

The citizens of Marseilles greeted the children kindly. Many found houses in which to

lodge. Others encamped in the streets. The next morning the whole expedition rushed down

to the harbor to see the sea divide before them. When the miracle did not take place,

there was bitter disappointment. Some of the children turned against Stephen, crying that

he had betrayed them, and began to retrace their steps. But most of them stayed on by the

sea-side, expecting each morning that God would relent. After a few days, two agents of

Satan appeared, merchants by trade, who, according to tradition, were Hugo Ferreus and

William Porcus (i.e. Hugh the Iron and William the Pig). They offered to put ships at

their disposal and to carry them free of charge, for the "glory of God," to

Palestine. Stephen eagerly accepted the kindly offer. Seven vessels were hired by the

merchants, and the children were taken aboard and set out to sea, as the priests on the

deck sang "Veni Creator Spiritus." Eighteen years passed before there was any

further news of them.

The citizens of Marseilles greeted the children kindly. Many found houses in which to

lodge. Others encamped in the streets. The next morning the whole expedition rushed down

to the harbor to see the sea divide before them. When the miracle did not take place,

there was bitter disappointment. Some of the children turned against Stephen, crying that

he had betrayed them, and began to retrace their steps. But most of them stayed on by the

sea-side, expecting each morning that God would relent. After a few days, two agents of

Satan appeared, merchants by trade, who, according to tradition, were Hugo Ferreus and

William Porcus (i.e. Hugh the Iron and William the Pig). They offered to put ships at

their disposal and to carry them free of charge, for the "glory of God," to

Palestine. Stephen eagerly accepted the kindly offer. Seven vessels were hired by the

merchants, and the children were taken aboard and set out to sea, as the priests on the

deck sang "Veni Creator Spiritus." Eighteen years passed before there was any

further news of them.

* * * * *

Meanwhile tales of Stephen's preaching had reached the Rhineland. The children of Germany were not to be outdone. A few weeks after Stephen had started on his mission, a boy called Nicholas, from a Rhineland village, began to preach the same message before the shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne. Like Stephen, he declared that children could do better than grown men, by their simple dependence on God Himself. He proclaimed that the sea would open to give them a path and that they would achieve their aim by the conversion of the infidel. Nicholas had a natural eloquence and was able to find eloquent disciples to carry his preaching further up and down the Rhineland. Within a few weeks an army of children had gathered at Cologne, ready to start out for Italy and the sea. It seems that the Germans were on an average slightly older than the French and that there were more girls with them. There was also a larger contingent of boys of the nobility, and a number of disreputable vagabonds. A few adults, mostly priests and nuns, also joined the movement. Many took up the pilgrims' costume with wide brim hats, walking staffs, gray coats and a cross sewn on their breasts.

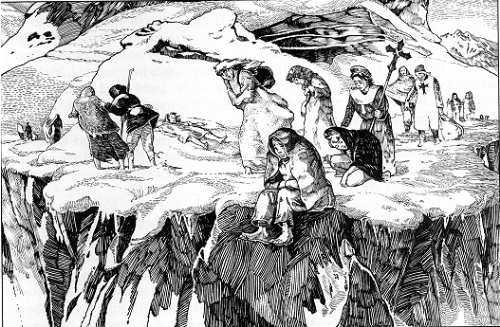

The expedition split into two parties. The first, numbering according to the chroniclers,

twenty thousand, was led by Nicholas himself; the second consisted in countless numbers of

smaller bands. Chronicles depicted the fair-haired army of little Germans as marching in

columns, singing the familiar Fairest Lord Jesus, otherwise titled, The

Crusaders' Hymn. It set out up the Rhine through western Switzerland, past

Geneva, to cross the treacherous Alps. It was an arduous journey for the children, and

their losses were heavy. As they began to climb to higher elevations, they encountered

frozen snows and freezing temperatures. Walking painfully, barefoot through the snow, many

suffered from frostbite. At night, the children huddled together to keep warm. Few carried

blankets, and at such high elevations, there was no wood to use for a fire. Weak from lack

of food, dozens died from exposure every night. With the frozen ground too hard for

digging graves, the survivors were left no choice but to leave the dead children where

they lay. The trails that led through the mountains were steep and rocky. The sharp rocks

cut the thinnest shoes to ribbons and slashed the children's feet. Some children

staggered off the trails and fell to their death down the steep canyon walls. Others sat

down to nurse their bleeding feet. Weak from continual hunger and a lack of oxygen at such

a high altitude, many never got up. They watched their comrades march on, then died in the

night as the cold overtook them. Less than a third of the company that left Cologne

appeared before the walls of Genoa, where they demanded a night's shelter within its

walls.

The expedition split into two parties. The first, numbering according to the chroniclers,

twenty thousand, was led by Nicholas himself; the second consisted in countless numbers of

smaller bands. Chronicles depicted the fair-haired army of little Germans as marching in

columns, singing the familiar Fairest Lord Jesus, otherwise titled, The

Crusaders' Hymn. It set out up the Rhine through western Switzerland, past

Geneva, to cross the treacherous Alps. It was an arduous journey for the children, and

their losses were heavy. As they began to climb to higher elevations, they encountered

frozen snows and freezing temperatures. Walking painfully, barefoot through the snow, many

suffered from frostbite. At night, the children huddled together to keep warm. Few carried

blankets, and at such high elevations, there was no wood to use for a fire. Weak from lack

of food, dozens died from exposure every night. With the frozen ground too hard for

digging graves, the survivors were left no choice but to leave the dead children where

they lay. The trails that led through the mountains were steep and rocky. The sharp rocks

cut the thinnest shoes to ribbons and slashed the children's feet. Some children

staggered off the trails and fell to their death down the steep canyon walls. Others sat

down to nurse their bleeding feet. Weak from continual hunger and a lack of oxygen at such

a high altitude, many never got up. They watched their comrades march on, then died in the

night as the cold overtook them. Less than a third of the company that left Cologne

appeared before the walls of Genoa, where they demanded a night's shelter within its

walls.

The Genoese authorities were ready at first to welcome the pilgrims, but on second thoughts they suspected a German plot, because Italy and Germany were at war. They would allow them to stay for one night only; but any who wished to settle permanently in Genoa were invited to do so. The children, expecting the sea to divide before them the next morning, were content. But the next morning the sea was as impervious to their prayers as it had been to the French at Marseilles. In their disillusion many of the children at once accepted the Genoese offer and became Genoese citizens, forgetting their pilgrimage. Several great families of Genoa later claimed to be descended from this alien immigration. But Nicholas and the greater number moved on. The sea would open for them elsewhere. A few days later they reached Pisa.

There they found two ships bound for Palestine, which agreed to take several of

the children, who embarked and who perhaps reached Palestine; but nothing is known of

their fate. Nicholas, however, still awaited a miracle, and trudged on with his faithful

followers to Rome. There the children met with Pope Innocent III. The leader of the

Catholic Church was amazed by the faith of the young Crusaders. "The children put

us to shame," Pope Innocent said. "They rush to recover the Holy Land

while we sleep." The pope did not encourage the young crusaders, however. He

could see from their tired faces and thin bodies that they could not go much further. And

He did not expect a miracle to open the way to the Holy Land. He told the children to go

home and wait for the day when He would call for their help in an adult crusade. The

children obeyed.

There they found two ships bound for Palestine, which agreed to take several of

the children, who embarked and who perhaps reached Palestine; but nothing is known of

their fate. Nicholas, however, still awaited a miracle, and trudged on with his faithful

followers to Rome. There the children met with Pope Innocent III. The leader of the

Catholic Church was amazed by the faith of the young Crusaders. "The children put

us to shame," Pope Innocent said. "They rush to recover the Holy Land

while we sleep." The pope did not encourage the young crusaders, however. He

could see from their tired faces and thin bodies that they could not go much further. And

He did not expect a miracle to open the way to the Holy Land. He told the children to go

home and wait for the day when He would call for their help in an adult crusade. The

children obeyed.

The second company of German crusaders was no more fortunate. They had travelled to Italy through central Switzerland and after great hardships reached the sea at Ancona. When the sea failed to divide for them they moved slowly down the east coast as far as Brindisi. At Brindisi the weary crusader children met greater cruelty than they endured anywhere else. Many of them were seized as slaves and abused cruelly. Hearing of the trouble, the local bishop did his best to stop the cruelties. He then met with the children and counseled them to return to their homes. Some of the children took the bishop's advice, but most stayed and waited for the promised miracle. There a few of them found ships sailing to Palestine and were given passages; but the others returned and began to wander slowly back again.

Little is known of the return journey. Those who had supported the Children's Crusade were disappointed by its outcome and felt foolish for having helped it. Some became angry, blaming their disappointment on the children, calling them "stupid children" or "an assembly of lunatic boys." As a result, the children received even less food, water, and shelter on their way home than they had on their crusade. One eyewitness told: "Many of the children died of hunger in the villages and on the roads, and nobody helped them."

Without a crusade to keep them together, the children's armies broke apart. Travelling alone or in small groups, the children had no defense against the people who wanted to enslave or abuse them. Another writer told: "They began to return. Those who had before traveled through countries in groups and parties, always singing, now returned alone and in silence, barefoot and hungry. Everyone laughed at them. Many were abused." Seeking safety, food and comfort, many of the children gave up on their ideas of returning home. Many decided to serve as monks and nuns at monasteries and convents along the way. Others were adopted by families. Less than one third of the more than 50,000 children who had joined the children's crusade ever returned home. At least 10,000 died.

Only a few stragglers found their way back next spring to the Rhineland. Nicholas was probably not amongst them. But the angry parents whose children had perished insisted on the arrest of his father, who had, it seems, encouraged the boy out of vainglory. He was taken and hanged.

* * * * *

Despite their miseries, they were perhaps luckier than the French. In the year

1230 a priest arrived in France from the East with a curious tale to tell. He had been, he

said, one of the young priests who had accompanied Stephen to Marseilles and had embarked

with them on the ships provided by the merchants. A few days out they had run into bad

weather, and two of the ships were wrecked on the island of San Pietro, off the south-west

corner of Sardinia, and all the passengers were drowned. The five ships that survived the

storm found themselves soon afterwards surrounded by a Muslim squadron from Africa; and

the passengers learned that they had been brought there by arrangement, to be sold into

captivity. They were all taken to the Algerian coast. Hundreds of the Christian children,

monks and nuns were sold to slave traders. Others, the young priest among them, were

shipped on to Egypt, where Frankish slaves fetched a better price. The sultan of Egypt

himself purchased 400 children and 80 priests. When they arrived at Alexandria the greater

part of the consignment was bought by the governor to work on his estates. According to

the priest, there were still about seven hundred of them living. A small company of

children was taken to the slave-markets of Baghdad and ordered by the Muslim princes to

accept the Islamic faith. The first child refused, so he was tortured. Still, he would not

deny his beliefs, so he was killed as an example to the rest. To the frustration of the

Muslim princes, the next child also refused to change his Faith. He, too, was tortured and

executed. The same for the third. And the fourth. In all, 18 children were killed before

the Muslim leaders gave up their diabolical plan to convert the Christian children by

force.

Despite their miseries, they were perhaps luckier than the French. In the year

1230 a priest arrived in France from the East with a curious tale to tell. He had been, he

said, one of the young priests who had accompanied Stephen to Marseilles and had embarked

with them on the ships provided by the merchants. A few days out they had run into bad

weather, and two of the ships were wrecked on the island of San Pietro, off the south-west

corner of Sardinia, and all the passengers were drowned. The five ships that survived the

storm found themselves soon afterwards surrounded by a Muslim squadron from Africa; and

the passengers learned that they had been brought there by arrangement, to be sold into

captivity. They were all taken to the Algerian coast. Hundreds of the Christian children,

monks and nuns were sold to slave traders. Others, the young priest among them, were

shipped on to Egypt, where Frankish slaves fetched a better price. The sultan of Egypt

himself purchased 400 children and 80 priests. When they arrived at Alexandria the greater

part of the consignment was bought by the governor to work on his estates. According to

the priest, there were still about seven hundred of them living. A small company of

children was taken to the slave-markets of Baghdad and ordered by the Muslim princes to

accept the Islamic faith. The first child refused, so he was tortured. Still, he would not

deny his beliefs, so he was killed as an example to the rest. To the frustration of the

Muslim princes, the next child also refused to change his Faith. He, too, was tortured and

executed. The same for the third. And the fourth. In all, 18 children were killed before

the Muslim leaders gave up their diabolical plan to convert the Christian children by

force.

>A less glorious fate awaited the young priests and the few others that were literate. The governor of Egypt, al-Adil's son al-Kamil, was interested in Western languages and letters. He bought them and kept them with him as interpreters, teachers and secretaries, and made no attempt to convert them to Islam. They stayed on in Cairo in a comfortable captivity; and eventually this one priest was released and allowed to return to France. He told the questioning parents of his comrades all that he knew, then disappeared into obscurity. A later story identified the two wicked merchants of Marseilles with two merchants who were hanged a few years afterwards for attempting to kidnap the Emperor Frederick on behalf of the Muslims, thus making them in the end pay the penalty for their crimes.

It was not the little children that would rescue Jerusalem, but many of them would set forth an example of courage, fortitude and zeal, that put to shame the adults of their day. Had these adults, particularly the nobles and other leaders, put aside their ceaseless fighting and squabbling over their temporal concerns (which they must necessarily abandon when they pass out of this world!) and answered the call of God given to them through the instrumentality of His Vicar on earth, Pope Innocent III, then these children would have been able to grow up in an atmosphere of normality. But that was not to be the case; and to credit of these young ones, if the adults were going to shirk their responsibilities, then they would take them upon themselves. In the eyes of man, they utterly failed; but in the eyes of God (which is all that matters), they were much beloved, and have no doubt reaped the reward so many of them have courageously earned.

* * * * *

Pope Gregory IX, who was pontiff between 1227 and 1241, groaned with

anguish when He learned of how these children suffered and died. He thought to raise a

memorial in their honor. The island of San Pietro, where the two ships foundered, was

deemed appropriate. Many small corpses had washed ashore during the storm and fishermen,

who sometimes visited the place, had buried them. His Holiness directed that a church

should be constructed and that the bodies of these children exhumed and reburied within.

Whether these bodies were found to be wondrously uncorrupted or not, has been a matter of

historical debate; however, some historians definitely state that their bodies were

incorruptible. It was called the Ecclesia Novorum Innocentium, the "Church of the New

Innocents," and a benefice supporting twelve monks was established for perpetual

prayer at the Church.

Pope Gregory IX, who was pontiff between 1227 and 1241, groaned with

anguish when He learned of how these children suffered and died. He thought to raise a

memorial in their honor. The island of San Pietro, where the two ships foundered, was

deemed appropriate. Many small corpses had washed ashore during the storm and fishermen,

who sometimes visited the place, had buried them. His Holiness directed that a church

should be constructed and that the bodies of these children exhumed and reburied within.

Whether these bodies were found to be wondrously uncorrupted or not, has been a matter of

historical debate; however, some historians definitely state that their bodies were

incorruptible. It was called the Ecclesia Novorum Innocentium, the "Church of the New

Innocents," and a benefice supporting twelve monks was established for perpetual

prayer at the Church.

For three centuries it was a favorite shrine until it fell out of favor and the monks left the island. In 1737, a party of Christian captives, escaping Muslim tyranny in Africa, landed there and found no trace of human habitation; only the ruins of the Church.

Thus concludes the story of the Children's Crusade.

Visit also: www.marienfried.com