Whereas the Greeks on this day are uniting in one solemnity the memory, as they express it, "of the illustrious Saints, the Twelve Apostles, worthy of all praise," let us follow in spirit the Roman people of former times, who would gather around the Successor of St. Peter and make the splendid Basilica of the Ostian Way—St. Paul outside the Walls—re-echo with songs of victory, while he offered to the Doctor of the Gentiles the grateful homage of the city and of the world.

On the 25th of January we beheld St. Stephen leading to Christ's Crib Saul, the once ravenous wolf of Benjamin (Gen. 49: 27), tamed at last, but who in the morning of his impetuous youth had filled the Church of God with tears and bloodshed. His evening did indeed come when, as Jacob had foreseen, Saul, the persecutor, would outstrip all his predecessors among Christ's disciples in giving increase to the fold, and in feeding the flock with the choicest food of his heavenly doctrine.

By an unexampled privilege, Our Lord, though already seated at the right hand of His Father, vouchsafed not only to call, but personally to instruct this new disciple, so that he might one day be numbered amongst His Apostles. The ways of God can never be contradictory one to another; hence this creation of a new Apostle may not be accomplished in a manner derogatory to the divine constitution already delivered to the Christian Church by the Son of God. Therefore, as soon as the illustrious convert emerged from those sublime contemplations during which the Christian dogma had been poured into his soul, he went to Jerusalem to see St. Peter, as he himself relates to his disciples in Galatia. "It behooved him," says Bossuet, "to collate his own Gospel with that of the Prince of the Apostles" (Sermon on Unity). From that moment, aggregated as a co-operator in the preaching of the Gospel, the Acts of the Apostles describes him at Antioch accompanied by St. Barnabas, presenting himself to the work of opening the Church to the Gentiles, the conversion of Cornelius having been already effected by St. Peter himself. He passes a whole year in this city, reaping an abundant harvest. After St. Peter's imprisonment in Jerusalem, at his subsequent departure for Rome, a warning from on high makes known to those who preside over the Church at Antioch, that the moment has come for them to impose hands on the two missionaries, and confer on them the sacred character of Ordination and Consecration.

From that hour St. Paul attains the full power of an Apostle, and it is clear that the mission for which he has been preparing is now opened. At the same time, in St. Luke's narrative, St. Barnabas almost disappears, retaining but a very secondary position. The new Apostle has his own disciples, and he henceforth takes the lead in a long series of pilgrimages marked by as many conquests. His first is to Cyprus, where he seals an alliance with ancient Rome, analogous to that which St. Peter contracted at Caesarea.

The Latin inscription reads: "Sergius Paulus, Proconsul of Asia, embraced the Christian Faith at the preaching of St. Paul."

In the year 43, when St. Paul landed in Cyprus, its proconsul was Sergius Paulus, illustrious for his ancestry, but still more so for the wisdom of his government. He wished to hear Sts. Paul and Barnabas: a miracle worked by St. Paul, under his very eyes, convinced him of the truth of his teaching; and the Christian Church counted that day among Her sons one who was heir to the proudest name among the noble families of Rome. Touching was the mutual exchange that took place on this occasion. The Roman patrician had just been freed by the Jew from the yoke of the Gentiles; in return, the Jew hitherto called Saul received and thenceforth adopted the name of Paul, as a trophy worthy of the Apostle of the Gentiles.

From Cyprus St. Paul travelled successively to Cilicia, Pamphylia, Pisidia, and Lycaonia, everywhere preaching the Gospel and founding churches. He then returned to Antioch in the year 47, and found the Church there in a state of violent agitation. A party of Jews, who had been converted to Christianity from the ranks of the Pharisees, whilst consenting indeed to the admission of Gentiles into the Church, were maintaining that this could only be on condition of their being likewise subjected to Mosaic practices, such as circumcision and the distinction of forbidden foods. The Christians who had been received from among the Gentiles were disgusted at this servitude to which St. Peter had not subjected them; and the controversy became so hot that St. Paul deemed it necessary to undertake a journey to Jerusalem, where St. Peter had lately arrived, a fugitive from Rome, and where the Apostolic College was at that moment further represented by St. John, as well as by St. James, the Bishop of that city. These being assembled to deliberate on the question, it was decreed, in the name and under the influence of the Holy Ghost, that to exact any observance relative to Jewish rites should be utterly forbidden in the case of Gentile converts. It was on this occasion, too, that St. Paul received from these Pillars, as he styles them, the confirmation of his apostolate superadded to that of the Twelve, and to be specially exercised in favor of the Gentiles. By this extraordinary ministry deputed to the nations, the Christian Church definitively asserted Her independence of Judaism, and the Gentiles could now freely come flocking into Her bosom.

St. Paul then resumed his course of apostolic journeys over all the provinces he had already evangelized, in order to confirm the Churches. Thence, passing through Phrygia, he came to Macedonia, stayed a while at Athens, and then on to Corinth, where he remained a year and a half. At his departure he left in this city a flourishing Church, whereby he excited against himself the fury of the Jews. From Corinth St. Paul went to Ephesus, where he stayed two years. So great was his success with the Gentiles there, that the worship of Diana was materially weakened (and the early converts burned their evil books—Acts 19: 19); whereupon a tumult ensuing, St. Paul thought the moment had come for his departure from Ephesus. During his abode there he made known to his disciples a thought that had long haunted him: "I must needs see Rome." The capital of the Gentile world was indeed calling the Apostle of the Gentiles.

St. Paul then resumed his course of apostolic journeys over all the provinces he had already evangelized, in order to confirm the Churches. Thence, passing through Phrygia, he came to Macedonia, stayed a while at Athens, and then on to Corinth, where he remained a year and a half. At his departure he left in this city a flourishing Church, whereby he excited against himself the fury of the Jews. From Corinth St. Paul went to Ephesus, where he stayed two years. So great was his success with the Gentiles there, that the worship of Diana was materially weakened (and the early converts burned their evil books—Acts 19: 19); whereupon a tumult ensuing, St. Paul thought the moment had come for his departure from Ephesus. During his abode there he made known to his disciples a thought that had long haunted him: "I must needs see Rome." The capital of the Gentile world was indeed calling the Apostle of the Gentiles.

The rapid growth of Christianity in the capital of the empire had brought face to face, in a manner more striking than elsewhere, the two heterogeneous elements which formed the Church of that day: the unity of Faith held together in one fold those that had formerly been Jews, and those that had been pagans. It so happened that some of both of these classes, too easily forgetting the gratuity of their common vocation to the Faith, began to go so far as to despise their brethren of the opposite class, deeming them less worthy than themselves of that Baptism which had made them all equal in Christ. On the one side, certain Jews disdained the Gentiles, remembering the polytheism which had sullied their past life with all those vices which came in its train. On the other side, certain Gentiles contemned the Jews, as coming from an ungrateful and blind people, who had so abused the favors lavished upon them by God as to crucify the Messias.

In the year 53, St. Paul, already aware of these debates, profited by a second journey to Corinth to write to the faithful of the Church in Rome that famous Epistle in which he emphatically sets forth how gratuitous is the gift of Faith; and maintains how Jew and Gentile alike being quite unworthy of the divine adoption, have been called solely by an act of pure mercy. He likewise shows how Jew and Gentile, forgetting the past, have but to embrace one another in the fraternity of the same Faith, thus testifying their gratitude to God through whom both of them have been alike prevented by grace. His apostolic dignity, so fully recognized, authorized St. Paul to interfere in this matter, though touching a Christian center not founded by him.

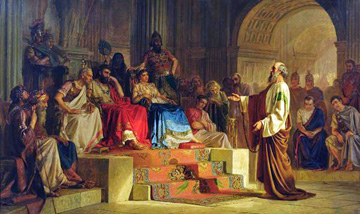

Whilst awaiting the day when he could behold with his own eyes the Queen of all Churches, lately fixed by St. Peter on the Seven Hills of Rome, the Apostle was once again anxious to make a pilgrimage to the City of David. Jewish rage was just at that moment rampant in Jerusalem against him; national pride being more specially piqued, in that he, the former disciple of Gamaliel, the accomplice of St. Stephen’s murder, should now invite the Gentiles to be coupled with the sons of Abraham, under the one same Law of Jesus of Nazareth. The tribune Lysias was scarce able to snatch him from the hands of these blood-thirsty men, ready to tear him to pieces. The following night, Christ appeared to St. Paul, saying to him: Be constant, for as thou hast testified of Me in Jerusalem, so must thou bear witness also at Rome.

It was not however, till after two years of captivity, that St. Paul, having appealed to Caesar, landed at Italy at the beginning of the year 56. Then at last the Apostle of the Gentiles made his entry into Rome: the trappings of a victor surrounded him not; he was but a humble Jewish prisoner led to the place where all appellants to Caesar were mustered; yet was he that Jew whom Christ Himself had conquered on the way to Damascus. No longer Saul, the Benjamite, he now presented himself under the Roman name of Paul; nor was this a robbery on his part, for after St. Peter, he was to be the second glory of Rome, the second pledge of her immortality. He brought not the Primacy with him indeed, as St. Peter had done, for that had been committed by Christ to one alone; but he came to assert in the very center of the Gentile world, the divine delegation which he had received in favor of the nations, just as an affluent flows into the main stream, which mingling its waters with its own, at last empties them united into the ocean. St. Paul was to have no successor in his extraordinary mission; but the element which he had deposited in Mother Church was of such value, that in the course of ages the Roman Pontiffs, heirs to St. Peter's monarchical power, have ever appealed to St. Paul's memory as well; pronouncing their mandates in the united names of the "Blessed Apostles Peter and Paul."

Instead of having to await in prison the day wherein his cause was to be heard, St. Paul was at liberty to choose a lodging place in the city. He was obliged, however, to be accompanied day and night by a soldier to whom, according to the usual custom, he was chained, but only in such a way as to prevent his escape; all his movements being otherwise left perfectly free, he could easily continue to preach the word of God. Towards the close of the year 57, in virtue of his appeal to Caesar, the Apostle was at last summoned to the praetorium; and the successful pleading of his cause resulted in his acquittal.

Instead of having to await in prison the day wherein his cause was to be heard, St. Paul was at liberty to choose a lodging place in the city. He was obliged, however, to be accompanied day and night by a soldier to whom, according to the usual custom, he was chained, but only in such a way as to prevent his escape; all his movements being otherwise left perfectly free, he could easily continue to preach the word of God. Towards the close of the year 57, in virtue of his appeal to Caesar, the Apostle was at last summoned to the praetorium; and the successful pleading of his cause resulted in his acquittal.

Being now free, St. Paul revisited the East, confirming on his Evangelical course the Churches he had previously founded. Thus Ephesus and Crete once more enjoyed his presence; in the one he left his disciple St. Timothy as Bishop, and in the other St. Titus. But St. Paul had not left Rome forever; marvelously illumined as she had been by his preaching, the Roman Church was yet to be gilded by his parting rays and empurpled with his blood. A heavenly warning, as in St. Peter's case, bade him also return to Rome where martyrdom was awaiting him. This fact is attested by St. Athanasius. We learn the same from St. Asterius of Amesius, who hereupon remarks that the Apostle entered Rome once more, "in order to teach the very masters of the world; and by their means to wrestle with the whole human race. There St. Paul found St. Peter engaged in the same work; he at once yoked himself to the same divine chariot with him, and set about instructing the children of the Law within the Synagogues, and the Gentiles outside."

At length Rome possessed her two Princes conjointly: the one seated on the eternal chair, holding in his hands the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven; the other surrounded by the sheaves he has garnered from the fields of the Gentile world. They would part no more; even in death, as the Church sings, they would not be separated. The period of their being together was necessarily short, for they must needs render to their divine Master the testimony of blood before the Roman world should be freed from the odious tyranny under which it was groaning. Their death was to be Nero's last crime; after that he was to fade from sight, leaving the world horror-stricken at his end, as shameful as it was tragic.

It was in the year 65 that St. Paul returned to Rome; once more signalizing his presence there by the manifold works of his apostolate. From the time of his first labors there, he had made converts even in the very palace of the Caesars: being now returned to this former theater of his zeal, he again found entrance into the imperial abode. A woman who was living in criminal intercourse with Nero, as likewise a cup-bearer of his, were both caught in the apostolic net, for it was hard indeed to resist the power of that mighty word. Nero, enraged at "this foreigner's" influence in his very household, was bent on St. Paul's destruction. Being first of all cast into prison, his zeal cooled not, but he persisted the more in preaching Jesus Christ. The two converts of the imperial palace having abjured, together with paganism, the manner of life they had been leading, this twofold conversion of theirs only hastened St. Paul's martyrdom. He was well aware that it would be so, as can be seen in these lines addressed to St. Timothy: "I labor even unto bonds as an evil-doer; but the word of God is not bound. Therefore I endure all things for the sake of the elect. For I am even now ready to be sacrificed, like a victim already sprinkled with the lustral water, and the time of my dissolution is at hand. I have fought the good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the Faith. As to the rest, there is laid up for me a crown of justice, which the Lord, the Just Judge, will render to me in that day." (2 Tim.)

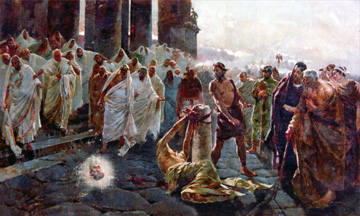

On the 29th day of June, in the year 67, while St. Peter, having crossed the Tiber by the Triumphal bridge, was drawing nigh to the cross prepared for him on the Vatican plain, another martyrdom was being consummated on the left bank of the same river. St. Paul, as he was led along the Ostian Way, was also followed by a group of the faithful who mingled with the escort of the condemned. His sentence was that he should be beheaded at the Salvian Waters. A march of two miles brought the soldiers to a path leading eastwards, by which they led their prisoner to the place fixed upon for the martyrdom of this, the Doctor of the Gentiles. St. Paul fell on his knees, addressing his last prayer to God; then having bandaged his eyes, he awaited the death-stroke. A soldier brandished his sword, and the Apostle's head, as it was severed from the trunk, made three bounds along the ground; three fountains immediately sprang up on these spots. Such is the local tradition; and to this day, three fountains are to be seen on the site of his martyrdom, over each of which an altar is raised.

On the 29th day of June, in the year 67, while St. Peter, having crossed the Tiber by the Triumphal bridge, was drawing nigh to the cross prepared for him on the Vatican plain, another martyrdom was being consummated on the left bank of the same river. St. Paul, as he was led along the Ostian Way, was also followed by a group of the faithful who mingled with the escort of the condemned. His sentence was that he should be beheaded at the Salvian Waters. A march of two miles brought the soldiers to a path leading eastwards, by which they led their prisoner to the place fixed upon for the martyrdom of this, the Doctor of the Gentiles. St. Paul fell on his knees, addressing his last prayer to God; then having bandaged his eyes, he awaited the death-stroke. A soldier brandished his sword, and the Apostle's head, as it was severed from the trunk, made three bounds along the ground; three fountains immediately sprang up on these spots. Such is the local tradition; and to this day, three fountains are to be seen on the site of his martyrdom, over each of which an altar is raised.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com