St. Ambrose, Bishop and Doctor of the Church (†397; Feast – December 7)

This illustrious pontiff was deservedly placed in the calendar of the Church side by side with the glorious Bishop of Myra. St. Nicholas confessed, at Nicaea, the divinity of the Redeemer; St. Ambrose, in his city of Milan, was the object of the hatred of the Arians, and, by his invincible courage, triumphed over the enemies of Christ. Let St. Ambrose, then, unite his voice, as Doctor of the Church, with that of St. Peter Chrysologus, and preach to the world the glories and the humiliations of the Messias. But, as Doctor of the Church, he has a special claim to our veneration: it is that among the bright luminaries of the Latin Church, four great masters head the list of sacred interpreters of the Faith: St. Gregory, St. Augustine, St. Jerome; and then our glorious St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, makes up the mystic number.

This illustrious pontiff was deservedly placed in the calendar of the Church side by side with the glorious Bishop of Myra. St. Nicholas confessed, at Nicaea, the divinity of the Redeemer; St. Ambrose, in his city of Milan, was the object of the hatred of the Arians, and, by his invincible courage, triumphed over the enemies of Christ. Let St. Ambrose, then, unite his voice, as Doctor of the Church, with that of St. Peter Chrysologus, and preach to the world the glories and the humiliations of the Messias. But, as Doctor of the Church, he has a special claim to our veneration: it is that among the bright luminaries of the Latin Church, four great masters head the list of sacred interpreters of the Faith: St. Gregory, St. Augustine, St. Jerome; and then our glorious St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, makes up the mystic number.

St. Ambrose owes his noble position in the calendar to the ancient custom of the Church, whereby, in the early ages, no Saint's feast was allowed to be kept in Lent. The day of his departure from this world and of his entrance into Heaven was the 4th of April, which, more frequently than not, comes during Lent; so that it was requisite that the memory of his sacred death should be solemnized on some other day, and the 7th of December naturally presented itself for such a feast, inasmuch as it was the anniversary of St. Ambrose's consecration as Bishop.

But, independently of these considerations, the road which leads us to Bethlehem could be perfumed by nothing so fragrant as this Feast of St. Ambrose. Does not the thought of this saintly and amiable Bishop impress us with the image of dignity and sweetness combined? Of the strength of the lion united with the gentleness of the dove? Time removes the deepest human impressions; but the memory of St. Ambrose is as vivid and dear in men's minds as though he were still among us. Who can ever forget the young, yet staid and learned governor of Liguria and Emilia, who comes to Milan as a simple catechumen, and finds himself forced, by the acclamations of the people, to ascend the Episcopal throne of this great city? And how indelibly impressed upon us are certain touching incidents of his early life! For instance, that beautiful presage of his irresistible eloquence—the swarm of bees coming round him as he was sleeping one day in his father's garden, and entering into his mouth, as though they would tell us how sweet that babe's words would be! And the prophetic gravity with which Ambrose, when quite a boy, would hold out his hand to his mother and sister, bidding them kiss it, for that one day it would be the hand of a bishop!

But what hard work awaited the neophyte of Milan, who was no sooner regenerated in the waters of Baptism, than he was ordained priest and consecrated Bishop! He had to apply himself, then and there, to close study of the Sacred Scriptures, that so he might prepare himself to become the defender of the Church, which was attacked, in the fundamental dogma of the Incarnation, by the false doctrine of the Arians. In a short time he attained such proficiency in the sacred sciences, as to become, like the prophet, a wall of brass, which checked the further progress of Arianism: moreover, the works written by St. Ambrose possess such plenitude and surety of doctrine, as to be numbered by the Church among the most faithful and authoritative interpretations of Her teaching.

But St. Ambrose had other and fiercer contests than those of religious controversy to encounter: his very life was more than once threatened by the heretics whom he had silenced. What a sublime spectacle was that—a Bishop blockaded in his church by the troops of the Empress Justina, and defended within by his people, day and night! Pastor and flock, both were admirable. How had St. Ambrose merited such fidelity and confidence on the part of his people? By a whole life spent for the welfare of his city and his country. He had never ceased to preach Jesus to all men; and now, the people saw their Bishop become, by his zeal, his devotedness, and his self-sacrificing conduct, a living image of Jesus.

In the midst of these dangers which threatened his person, his great soul was calm and seemingly unconscious of the fury of his enemies. It was on that very occasion that he instituted, at Milan, the choral singing of the psalms. Up to that time, the holy canticles had been given from the ambo by the single voice of a lector; but Ambrose, shut up in his basilica with his people, took the opportunity, and formed two choirs, bidding them respond to each other the verses of the psalms. The people forgot their trouble in the delight of this heavenly music; nay, the very howling of the tempest, and the fierceness of the siege they were sustaining, added enthusiasm to this first exercise of their new privilege. Such was the chivalrous origin of alternate psalmody in the western Church. Rome adopted the practice which St. Ambrose was the first to introduce, and which will continue to be observed to the end of time. During these hours of struggle with his enemies, the glorious Bishop had another gift wherewith to enrich the faithful people who were defending him at the risk of their own lives. St. Ambrose was a poet, and he had frequently sung, in verses full of sweetness and sublimity, the greatness of the true God, and the mysteries of man's salvation. He now gave to his devoted people these hymns, which he had composed only for his own private devotion. The basilicas of Milan soon echoed these accents of the sublime soul which first uttered them. Later on, the whole Latin Church adopted them; and in honor of the richest sources of the sacred liturgy, a hymn was, for a long time, called after him, an Ambrosian. The Divine Office thus received a new mode of celebrating the divine praise, and the Church, the Bride of Christ, possessed one more means of giving expression to the sentiments which animate Her.

Thus, our hymns and the alternate chanting of the psalms are trophies of St. Ambrose's victory. He had been raised up by God not for his own age alone, but also for those which were to follow. Hence, the Holy Ghost infused into him the knowledge of Christian jurisprudence, that he might be the defender of the rights of the Church at a period when paganism still lived, though defeated; and imperialism, or caesarism, had still the instinct, though not the uncontrolled power, to exercise its tyranny. St. Ambrose's law was the Gospel, and he would acknowledge no law which was in opposition to that. He could not understand such imperial policy as that of ordering a basilica to be given up to the Arians, for the sake of peace! He would defend the inheritance of the Church; and in that defense, was ready to shed the last drop of his blood. Certain courtiers dared to accuse him of tyranny: "No," answered the Saint, "Bishops are not tyrants, but have often to suffer from tyranny." The eunuch Calligonus, high chamberlain of the Emperor Valentinian II, had said to St. Ambrose: "What! Darest thou in my presence to care so little for Valentinian! I will cut off thy head!." "I would it might be so," answered St. Ambrose, "I should then die as a Bishop, and thou wouldst have done what eunuchs are wont to do."

Thus, our hymns and the alternate chanting of the psalms are trophies of St. Ambrose's victory. He had been raised up by God not for his own age alone, but also for those which were to follow. Hence, the Holy Ghost infused into him the knowledge of Christian jurisprudence, that he might be the defender of the rights of the Church at a period when paganism still lived, though defeated; and imperialism, or caesarism, had still the instinct, though not the uncontrolled power, to exercise its tyranny. St. Ambrose's law was the Gospel, and he would acknowledge no law which was in opposition to that. He could not understand such imperial policy as that of ordering a basilica to be given up to the Arians, for the sake of peace! He would defend the inheritance of the Church; and in that defense, was ready to shed the last drop of his blood. Certain courtiers dared to accuse him of tyranny: "No," answered the Saint, "Bishops are not tyrants, but have often to suffer from tyranny." The eunuch Calligonus, high chamberlain of the Emperor Valentinian II, had said to St. Ambrose: "What! Darest thou in my presence to care so little for Valentinian! I will cut off thy head!." "I would it might be so," answered St. Ambrose, "I should then die as a Bishop, and thou wouldst have done what eunuchs are wont to do."

This noble courage in the defense of the rights of the Church showed itself even more clearly on another occasion. The Roman senate, or rather that portion of the senate which, though a minority, was still pagan, was instigated by Symmachus, the prefect of Rome, to ask the Emperor for the rebuilding of the altar of victory in the Capitol, under the pretext of averting the misfortunes which threatened the Empire. St. Ambrose, who had said to these politicians, "I hate the religion of the Neros," vehemently opposed this last effort of idolatry. He presented most eloquent petitions to Valentinian, in which he protested against an attempt which aimed at bringing a Christian prince to recognize that false doctrines have rights, and which would, if permitted to be tried, rob the one only Master of nations of the victories which He had won. Valentinian yielded to these earnest remonstrances, which taught him "that a Christian Emperor can honor only one altar—the altar of Christ;" and when the senators had to receive their answer, the prince told them that Rome was his mother, and he loved her: but that God was his Savior, and he would obey Him.

If the Empire of Rome had not been irrevocably condemned by God to destruction, the influence which St. Ambrose had over such well-intentioned princes as Valentinian would probably have saved it. The Saint's maxim was a strong one; but it was not to be realized until new kingdoms, springing up out of the ruins of the Roman Empire, should be organized by the Catholic Church. "An Emperor's grandest title," said St. Ambrose, "is to be a son of the Church. An Emperor is in the Church, not over Her."

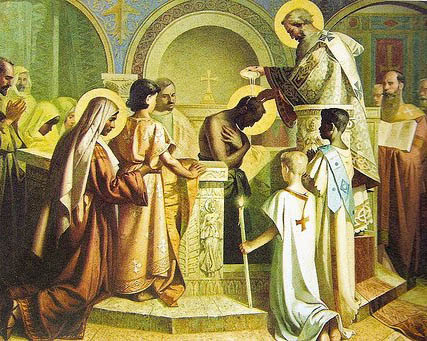

It is beautiful to see the affectionate solicitude of St. Ambrose for the young Emperor Gratian, at whose death he shed floods of tears. How tenderly, too, did he love Theodosius, that model Christian prince, for whose sake God retarded the fall of the Empire, by the uninterrupted victory over all its enemies! On one occasion, indeed, this son of the Church showed in himself the pagan Caesar; but his holy father Ambrose, by a severity which was inflexible because his affection for the culprit was great, brought him back to his duty and his God. "I loved," says the holy Bishop, in the funeral oration which he preached over Theodosius, "I loved this prince, who preferred correction to flattery. He stripped himself of his royal robes and publicly wept in the Church for the sin he had committed, and into which he had been led by evil counsel. In sighs and tears he sought to be forgiven. He, an Emperor, did what common men would be ashamed to do—he did public penance; and for the rest of his life, he passed not a day without bewailing his sin." (See image above.)

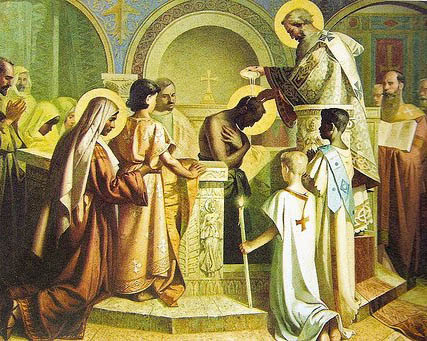

But we would have a very false idea of St. Ambrose if we thought that he turned his attention only to affairs of importance like these, which brought him before the notice of the world. No pastor could be more solicitous than he about the slightest detail which affected the interests of his flock. We have his life written by his deacon, Paulinus, who knew secrets which intimacy alone can know, and these fortunately he has revealed to us. Among other things, he tells us that when St. Ambrose heard confessions, he shed so many tears that the sinner was forced to weep: "You would have thought," says Paulinus, "that they were his own sins that he was listening to." We all know the tender interest he felt for St. Augustine, when he was a slave to error and to his own passions; and if we would have a faithful portrait of St. Ambrose, we must read in the Confessions of the Bishop of Hippo the fine passage where he expresses his admiration and gratitude for his spiritual father. St. Ambrose had told St. Monica that her son St. Augustine, who gave her so much anxiety, would be converted. That happy day at last came; it was St. Ambrose's hand which immersed in the cleansing waters of Baptism him who was to be the prince of the Doctors of the Church.

But we would have a very false idea of St. Ambrose if we thought that he turned his attention only to affairs of importance like these, which brought him before the notice of the world. No pastor could be more solicitous than he about the slightest detail which affected the interests of his flock. We have his life written by his deacon, Paulinus, who knew secrets which intimacy alone can know, and these fortunately he has revealed to us. Among other things, he tells us that when St. Ambrose heard confessions, he shed so many tears that the sinner was forced to weep: "You would have thought," says Paulinus, "that they were his own sins that he was listening to." We all know the tender interest he felt for St. Augustine, when he was a slave to error and to his own passions; and if we would have a faithful portrait of St. Ambrose, we must read in the Confessions of the Bishop of Hippo the fine passage where he expresses his admiration and gratitude for his spiritual father. St. Ambrose had told St. Monica that her son St. Augustine, who gave her so much anxiety, would be converted. That happy day at last came; it was St. Ambrose's hand which immersed in the cleansing waters of Baptism him who was to be the prince of the Doctors of the Church.

A heart thus loyal in its friendship could not but be affectionate to those who were related by ties of blood. He tenderly loved his brother Satyrus, as we may see from the two funeral orations which he has left us upon this brother, wherein he speaks his praises with all the warmth of enthusiastic admiration. He had a sister, too, named Marcellina, who was equally dear to her saintly brother. From her earliest years, she had spurned the world and its pomps, and the position which she might expect to enjoy in it, being a patrician's daughter. She had received the veil of virginity from the hands of Pope Liberius, but lived in her father's house at Rome. Her brother St. Ambrose was separated from her, but he seemed to love her the more for that; and he communicated with her in her holy retirement by frequent letters, several of which are still extant. She deserved all the esteem which St. Ambrose had for her; she had a great love for the Church of God, and she was heart and soul in all the great undertakings of her brother the Bishop. The very heading of these letters shows the affection of the Saint: "The brother to the sister;" or "To my sister Marcellina, dearer to me than mine own eyes and life." Then follows the letter, in an energetic and animated style, well suited to the soul-stirring communications he had to make to her about his struggles. One of them was written in the midst of the storm, when the courageous Pontiff was besieged in his basilica by Justina’s soldiers. His discourses to the people of Milan, his consolations and his trials, the heroic sentiments of his great soul, all is told in these dispatches to his sister, where every line shows how strong and holy was the attachment between them. The great basilica of Milan still contains the tombs of the brother and sister.

Such was St. Ambrose, of whom Theodosius was one day heard to say: "There is but one Bishop in the world." Let us glorify the Holy Ghost, Who has vouchsafed to produce this sublime model in the Church, and let us beg of the holy Pontiff to obtain for us, by his prayers, a share in that lively faith and ardent love which he himself had, and which he has left us on the mystery of the Incarnation. During these days, which are preparing us for the Birth of our Incarnate Lord, St. Ambrose is one of our most powerful patrons.

His love toward the Blessed Mother of God teaches us what admiration and love we ought to have for Mary. St. Ephrem and St. Ambrose are the two Fathers of the fourth century who are the most explicit upon the glories of the office and the person of the Mother of Jesus. To confine ourselves to St. Ambrose, he has completely mastered this mystery, which he understood, appreciated, and defined in his writings. Mary's exemption from every stain of sin; Mary's uniting Herself, at the foot of the Cross, with Her Divine Son for the salvation of the world; Jesus' appearing, after His Resurrection, to Mary first of all—on these and so many other points St. Ambrose has spoken so clearly as to deserve to be considered one of the most prominent witnesses of the primitive traditions respecting the privileges and dignity of the Holy Mother of God.

This his devotion to Mary explains St. Ambrose's enthusiastic admiration for the holy state of Christian virginity, of which he might justly be called the Doctor. He surpasses all the Fathers in the beautiful and eloquent manner in which he speaks of the dignity and happiness of virginity. Four of his writings are devoted to the praises of this sublime state. The pagans would fain have an imitation of it by instituting the seven Vestal virgins, whom they loaded with honors and riches, and to whom they in due time restored liberty. St. Ambrose shows how contemptible these were, compared with the innumerable virgins of the Christian Church, who filled the whole world with the fragrance of their humility, constancy, and disinterestedness. But on this magnificent subject, his words were even more telling than his writings; and we learn from his contemporaries, that when he went to preach in any town, worldly mothers would frequently not allow their daughters to be present at his sermons, for fear that this irresistible panegyrist of the eternal nuptials with the Lamb would convince them that this was the better part, and persuade them to make it the object of their desires.

It is time to read the account of the virtues of the great Saint of Milan, given us by the Church:

St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, was the son of a Roman citizen, whose name was also Ambrose, and who held the office of Prefect of Cisalpine Gaul. It is related that when the Saint was an infant, a swarm of bees rested on his lips; it was a presage of his future extraordinary eloquence. He was educated in the liberal arts at Rome, and not long after was appointed, by the Prefect Probus, to be Governor of Liguria and Emilia, whence, later on, he was sent, by order of the same Probus, to Milan, with power of Judge; for the people of that city were quarrelling among themselves about the successor of the Arian Bishop, Auxentius, who had died. Wherefore, Ambrose, having entered the Church that he might fulfill the duty that had been imposed on him, and quell the disturbance that had arisen, delivered an eloquent discourse on the advantages of peace and tranquility in a State. Scarcely had he finished speaking, than a boy exclaimed: "Ambrose, bishop!" The whole multitude shouted: "Ambrose, bishop!"

On his refusing to accede to their entreaties, the earnest request of the people was presented to the Emperor Valentinian, who was gratified that they whom he selected as judges were thus sought after to be made priests. It was also pleasing to the Prefect Probus, who, as though he foresaw the event, had said to St. Ambrose on his setting out: "Go, act not as judge, but as bishop!" The desire of the people being thus seconded by the will of the Emperor, St. Ambrose was baptized (for he was only a catechumen), and was admitted to Sacred Orders, ascending by all the degrees of Orders as proscribed by the Church; and on the eighth day, which was the seventh of the Ides of December (December 7), he received the burden of the episcopacy. Being made Bishop, he most strenuously defended the Catholic Faith and ecclesiastical discipline. He converted to the true Faith many Arians and other heretics, among whom was that brightest luminary of the Church, St. Augustine, the spiritual child of St. Ambrose in Jesus Christ.

On his refusing to accede to their entreaties, the earnest request of the people was presented to the Emperor Valentinian, who was gratified that they whom he selected as judges were thus sought after to be made priests. It was also pleasing to the Prefect Probus, who, as though he foresaw the event, had said to St. Ambrose on his setting out: "Go, act not as judge, but as bishop!" The desire of the people being thus seconded by the will of the Emperor, St. Ambrose was baptized (for he was only a catechumen), and was admitted to Sacred Orders, ascending by all the degrees of Orders as proscribed by the Church; and on the eighth day, which was the seventh of the Ides of December (December 7), he received the burden of the episcopacy. Being made Bishop, he most strenuously defended the Catholic Faith and ecclesiastical discipline. He converted to the true Faith many Arians and other heretics, among whom was that brightest luminary of the Church, St. Augustine, the spiritual child of St. Ambrose in Jesus Christ.

When the Emperor Gratian was killed by Maximus, St. Ambrose was twice deputed to go to the murderer and insist on his doing penance for his crime; when he refused to do so, St. Ambrose refused to have communion with him. The Emperor Theodosius having made himself guilty of the massacre at Thessalonica was forbidden by the Saint to enter the church. On the Emperor's excusing himself by saying that King David had also committed murder and adultery, St. Ambrose replied: "Thou hast imitated his sin; now imitate his repentance." Upon which Theodosius humbly performed the public penance which the Bishop imposed upon him. The holy Bishop having thus gone through the greatest labors and solicitudes for God's Church, and having written several admirable books, foretold the day of his death, before he was taken with his last sickness. Honoratus, the Bishop of Vercelli, was thrice admonished by the voice of God to go to the dying Saint: he went, and administered to him the Sacred Body of Our Lord. St. Ambrose having received Viaticum, prayed with his hands in the form of a cross, and yielded his soul up to God on the eve of the Nones of April (April 4), in the year of Our Lord 397. (St. Ambrose is buried along with the relics of Ss. Gervase and Protase which he had miraculously discovered—see image above.)

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Back to Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

This illustrious pontiff was deservedly placed in the calendar of the Church side by side with the glorious Bishop of Myra. St. Nicholas confessed, at Nicaea, the divinity of the Redeemer; St. Ambrose, in his city of Milan, was the object of the hatred of the Arians, and, by his invincible courage, triumphed over the enemies of Christ. Let St. Ambrose, then, unite his voice, as Doctor of the Church, with that of St. Peter Chrysologus, and preach to the world the glories and the humiliations of the Messias. But, as Doctor of the Church, he has a special claim to our veneration: it is that among the bright luminaries of the Latin Church, four great masters head the list of sacred interpreters of the Faith: St. Gregory, St. Augustine, St. Jerome; and then our glorious St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, makes up the mystic number.

This illustrious pontiff was deservedly placed in the calendar of the Church side by side with the glorious Bishop of Myra. St. Nicholas confessed, at Nicaea, the divinity of the Redeemer; St. Ambrose, in his city of Milan, was the object of the hatred of the Arians, and, by his invincible courage, triumphed over the enemies of Christ. Let St. Ambrose, then, unite his voice, as Doctor of the Church, with that of St. Peter Chrysologus, and preach to the world the glories and the humiliations of the Messias. But, as Doctor of the Church, he has a special claim to our veneration: it is that among the bright luminaries of the Latin Church, four great masters head the list of sacred interpreters of the Faith: St. Gregory, St. Augustine, St. Jerome; and then our glorious St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, makes up the mystic number. Thus, our hymns and the alternate chanting of the psalms are trophies of St. Ambrose's victory. He had been raised up by God not for his own age alone, but also for those which were to follow. Hence, the Holy Ghost infused into him the knowledge of Christian jurisprudence, that he might be the defender of the rights of the Church at a period when paganism still lived, though defeated; and imperialism, or caesarism, had still the instinct, though not the uncontrolled power, to exercise its tyranny. St. Ambrose's law was the Gospel, and he would acknowledge no law which was in opposition to that. He could not understand such imperial policy as that of ordering a basilica to be given up to the Arians, for the sake of peace! He would defend the inheritance of the Church; and in that defense, was ready to shed the last drop of his blood. Certain courtiers dared to accuse him of tyranny: "No," answered the Saint, "Bishops are not tyrants, but have often to suffer from tyranny." The eunuch Calligonus, high chamberlain of the Emperor Valentinian II, had said to St. Ambrose: "What! Darest thou in my presence to care so little for Valentinian! I will cut off thy head!." "I would it might be so," answered St. Ambrose, "I should then die as a Bishop, and thou wouldst have done what eunuchs are wont to do."

Thus, our hymns and the alternate chanting of the psalms are trophies of St. Ambrose's victory. He had been raised up by God not for his own age alone, but also for those which were to follow. Hence, the Holy Ghost infused into him the knowledge of Christian jurisprudence, that he might be the defender of the rights of the Church at a period when paganism still lived, though defeated; and imperialism, or caesarism, had still the instinct, though not the uncontrolled power, to exercise its tyranny. St. Ambrose's law was the Gospel, and he would acknowledge no law which was in opposition to that. He could not understand such imperial policy as that of ordering a basilica to be given up to the Arians, for the sake of peace! He would defend the inheritance of the Church; and in that defense, was ready to shed the last drop of his blood. Certain courtiers dared to accuse him of tyranny: "No," answered the Saint, "Bishops are not tyrants, but have often to suffer from tyranny." The eunuch Calligonus, high chamberlain of the Emperor Valentinian II, had said to St. Ambrose: "What! Darest thou in my presence to care so little for Valentinian! I will cut off thy head!." "I would it might be so," answered St. Ambrose, "I should then die as a Bishop, and thou wouldst have done what eunuchs are wont to do." But we would have a very false idea of St. Ambrose if we thought that he turned his attention only to affairs of importance like these, which brought him before the notice of the world. No pastor could be more solicitous than he about the slightest detail which affected the interests of his flock. We have his life written by his deacon, Paulinus, who knew secrets which intimacy alone can know, and these fortunately he has revealed to us. Among other things, he tells us that when St. Ambrose heard confessions, he shed so many tears that the sinner was forced to weep: "You would have thought," says Paulinus, "that they were his own sins that he was listening to." We all know the tender interest he felt for St. Augustine, when he was a slave to error and to his own passions; and if we would have a faithful portrait of St. Ambrose, we must read in the Confessions of the Bishop of Hippo the fine passage where he expresses his admiration and gratitude for his spiritual father. St. Ambrose had told St. Monica that her son St. Augustine, who gave her so much anxiety, would be converted. That happy day at last came; it was St. Ambrose's hand which immersed in the cleansing waters of Baptism him who was to be the prince of the Doctors of the Church.

But we would have a very false idea of St. Ambrose if we thought that he turned his attention only to affairs of importance like these, which brought him before the notice of the world. No pastor could be more solicitous than he about the slightest detail which affected the interests of his flock. We have his life written by his deacon, Paulinus, who knew secrets which intimacy alone can know, and these fortunately he has revealed to us. Among other things, he tells us that when St. Ambrose heard confessions, he shed so many tears that the sinner was forced to weep: "You would have thought," says Paulinus, "that they were his own sins that he was listening to." We all know the tender interest he felt for St. Augustine, when he was a slave to error and to his own passions; and if we would have a faithful portrait of St. Ambrose, we must read in the Confessions of the Bishop of Hippo the fine passage where he expresses his admiration and gratitude for his spiritual father. St. Ambrose had told St. Monica that her son St. Augustine, who gave her so much anxiety, would be converted. That happy day at last came; it was St. Ambrose's hand which immersed in the cleansing waters of Baptism him who was to be the prince of the Doctors of the Church. On his refusing to accede to their entreaties, the earnest request of the people was presented to the Emperor Valentinian, who was gratified that they whom he selected as judges were thus sought after to be made priests. It was also pleasing to the Prefect Probus, who, as though he foresaw the event, had said to St. Ambrose on his setting out: "Go, act not as judge, but as bishop!" The desire of the people being thus seconded by the will of the Emperor, St. Ambrose was baptized (for he was only a catechumen), and was admitted to Sacred Orders, ascending by all the degrees of Orders as proscribed by the Church; and on the eighth day, which was the seventh of the Ides of December (December 7), he received the burden of the episcopacy. Being made Bishop, he most strenuously defended the Catholic Faith and ecclesiastical discipline. He converted to the true Faith many Arians and other heretics, among whom was that brightest luminary of the Church, St. Augustine, the spiritual child of St. Ambrose in Jesus Christ.

On his refusing to accede to their entreaties, the earnest request of the people was presented to the Emperor Valentinian, who was gratified that they whom he selected as judges were thus sought after to be made priests. It was also pleasing to the Prefect Probus, who, as though he foresaw the event, had said to St. Ambrose on his setting out: "Go, act not as judge, but as bishop!" The desire of the people being thus seconded by the will of the Emperor, St. Ambrose was baptized (for he was only a catechumen), and was admitted to Sacred Orders, ascending by all the degrees of Orders as proscribed by the Church; and on the eighth day, which was the seventh of the Ides of December (December 7), he received the burden of the episcopacy. Being made Bishop, he most strenuously defended the Catholic Faith and ecclesiastical discipline. He converted to the true Faith many Arians and other heretics, among whom was that brightest luminary of the Church, St. Augustine, the spiritual child of St. Ambrose in Jesus Christ.