James Spencer Northcote was a convert to Catholicism, having been a married Anglican minister. At the death of his wife, also a convert, he entered the Catholic priesthood and eventually became president of St. Mary’s College at Oscott. Between the years 1856 and 1860 he gave a series of lectures to refute the Protestant claim that, according to the Bible, the Blessed Virgin Mary is nothing but an ordinary woman. They were later published, and furnish some of the best rebuttals in print against those who attack Catholic devotion to our Beloved Mother Mary. We present them in a slightly condensed form.

Pray one for another that you may be saved; for the continual prayer of a just man availeth much (James 5: 16).

We have spoken of the duty of honoring our Blessed Lady by celebrating Her praises and imitating Her virtues; but there remains yet another part of Catholic devotion towards Her which requires to be explained and justified—I mean our frequent invocations of Her, our continual appeals to Her intercession with God in our behalf. These, it is said, involve a practical denial of the sovereign power or goodness of God, to Whom alone we should have recourse in our necessities. What, then, is invocation, and why do we invoke the Blessed Virgin and all the Saints? To invoke is to call to our aid, when some want, or danger, or difficulty oppresses us, to which we feel our own weakness to be unequal. A poor man invokes, or calls out for, the help of the rich man; the weak, of the strong; the ignorant, of the learned. Do they err in so doing? Are they justly chargeable with impiety and denial of God's goodness or power when they do these things? After all, it is certain that every good gift comes from God; that He alone is abundantly sufficient to supply our wants, and that He is ever more ready to give than we to ask. Why, then, does not the beggar turn only to Him in his distress, and ask Him to supply his needs, as He supplied those of Elias of old? Or why does not the sick man look only to Him, Who is the author of life and death, and Who could heal by a single word? Surely because all mankind, while fully acknowledging that "no man can receive anything except it be given him from Heaven" (John 3: 27), yet recognize this other truth also, that it is God's good pleasure, in the ordinary way of His Providence, to distribute His gifts, not immediately from His own hand, but through the instrumentality of others; thus making us dependent on one another and uniting all together in the closest bonds of fellowship as one body.

But it is objected, though this may be very true with reference to the goods of this life, health of body, food, clothing, and the like, yet in all spiritual matters we depend on God alone; none can intervene here between man and his Maker; or, at least, there can be no necessity for such intervention. But how can you be sure of this? The same God is the Author of nature and of grace, and why should they not be subject to the same laws? Is it not more reasonable to expect that they should be so than that they should not? But—better than any mere speculation and conjecture—let us look into Holy Scripture, and see whether we cannot there find some direct information on the subject. Open the very first book of the Bible (Genesis 20), and you will find the story of a king who offends God by taking another man's wife. It is true, indeed, that he did not know that Sarah was Abraham's wife; so far, he had acted with a sincere heart; nevertheless there was that in his conduct which offended God, and which He determined to punish. But "Abimelech prayed to God, and said, 'Lord, wilt Thou slay a nation that is ignorant and just?' And God said, 'Restore the man his wife, for he is a prophet'."—I have already told you it was Abraham—and God adds, " 'And Abraham shall pray for thee, and thou shalt live'." And by-and-by at the end of the chapter we read, "When Abraham prayed, God healed Abimelech and his wife." What is this but intercession of the Saints in patriarchal times? If you ask why it is that God did not choose to grant Abimelech's own prayer taken alone, but insisted that it should be strengthened by the prayer of Abraham, we are silent, for "Who hath known the mind of the Lord, or who hath been His counselor?" (Rom. 11: 34) We are only concerned to show the fact that God made the intercession of the prophet an essential condition of His forgiveness of the king.

Nor is this the only instance of the same law which has been recorded for our instruction. You remember the history of Job and his three comforters—what was the end of that history? "The Lord said to Eliphaz, 'My wrath is kindled against thee and against thy two friends, because you have not spoken the thing that is right before Me, as my servant Job hath. Take unto you, therefore, seven oxen and seven rams, and go to My servant Job, and offer for yourselves a holocaust; and My servant Job shall pray for you; his face I will accept, that folly be not imputed to you...' So they did as the Lord had spoken to them, and the Lord accepted the face of Job. The Lord also was turned at the penance of Job, when he prayed for his friends" (Job 42: 7, 8, 10).

Again, God laments, by the mouth of His prophet Ezechiel, that there is no Saint to intercede for His people, to intervene between their sins and His just anger (Ezech. 22: 30); and at another time He says that even though there were Saints to intercede, yet so great is His anger, He would not forgive (Ezech. 14: 14-16; Jer. 15: 1).

But why multiply examples? A single undoubted instance of God's will is sufficient; for "He is not a man that He should change, nor the son of man that He should repent;" and since it is quite clear that under the Old Law God attributed much weight to the prayers of holy men interceding for others, we are sure that it must be so still, unless we are told to the contrary. Accordingly we find St. Paul earnestly soliciting the prayers of the early Christians, saying, "I beseech you, brethren, through Our Lord Jesus Christ, and by the charity of the Holy Ghost, that you help me in your prayers for me to God" (Rom. 15: 30), and again to the Thessalonians (2 Thes. 3: 1), "Brethren, pray for us." And indeed, who is there among non-Catholics, who fancies himself in earnest about his salvation, who has not asked for the prayers of his friends whom he believed to be good and holy men, acceptable to God? And in proportion to his estimation of their piety is the value he sets upon their intercession. And does he fear that by so doing he is offending God; robbing Him of any honor and glory that is His due? On the contrary, he knows that he is obeying God's own command, Who expressly bids us "pray one for another, that you may be saved; because the continual prayer of a just man availeth much."

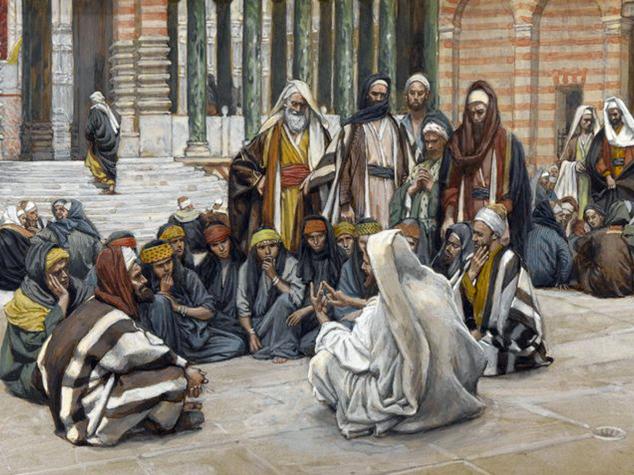

But if this be so, if it is clearly God's will that we should ask the prayers of our fellow-men, who are still affected by the infirmities of the flesh, and therefore liable to fall away from grace and to lose their souls, why should we hesitate to ask the prayers also of the Saints in Heaven who see God face to face? Is it because the Saint is not living but dead? To give such a reason as this would be, in fact, to express a doubt as to the immortality of the soul. The Church teaches us to call the day of a Saint's death or departure out of this world his birthday, implying that he only then truly begins to live. God is called the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; "He is not the God of the dead, but of the living," as Our Lord taught in the temple (Matt. 22; 32). We do not lose our friends when they die; we gain them, and gain them forever, if they die in the Lord. Not for us do the glorious army of Martyrs, the bright choir of Virgins and purified souls who honored their Lord in the flesh, sleep now in the cold grave, or lie torpid in some unknown indefinite place. They are already full of life, a life of joy, contentment, and power, in comparison with which what we call life is only a living death.

But if this be so, if it is clearly God's will that we should ask the prayers of our fellow-men, who are still affected by the infirmities of the flesh, and therefore liable to fall away from grace and to lose their souls, why should we hesitate to ask the prayers also of the Saints in Heaven who see God face to face? Is it because the Saint is not living but dead? To give such a reason as this would be, in fact, to express a doubt as to the immortality of the soul. The Church teaches us to call the day of a Saint's death or departure out of this world his birthday, implying that he only then truly begins to live. God is called the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; "He is not the God of the dead, but of the living," as Our Lord taught in the temple (Matt. 22; 32). We do not lose our friends when they die; we gain them, and gain them forever, if they die in the Lord. Not for us do the glorious army of Martyrs, the bright choir of Virgins and purified souls who honored their Lord in the flesh, sleep now in the cold grave, or lie torpid in some unknown indefinite place. They are already full of life, a life of joy, contentment, and power, in comparison with which what we call life is only a living death.

Is it then that the Saints have ceased to love us? "We ought not to fear," says St. Augustine, "that the Saints will forget us, now that they drink of Thee, O God, Who art ever mindful of us" (Confessions 9: 3). "Far be from us," says St. Bernard, "the thought that that love which we have seen so active upon earth should be lessened or destroyed in Heaven, where the Saints drink at the very source and fountain-head of that love of which here upon earth they had only a few drops. The love of those who have gone before us and passed through the valley of the shadow of death cannot fail, for love is stronger than death. Yes, my brethren, the breadth of Heaven enlarges men's hearts, not contracts them; fills them with more love, not empties them of what they had before. In the light of God, the memory is brightened and strengthened, not obscured; what was not known is now learned; not what was known, unlearned. In a word, it is Heaven and not earth" (De Obitu Malachiae); and Heaven is not a land of separation or of forgetfulness. There is but one Body of the faithful, whether in Heaven or upon earth, and Jesus Christ is their Head, and through Him there is a communion between all the members of His Mystical Body. Those who have entered into their rest have not thereby ceased to be our brethren and to love us. Neither have they ceased, on the other hand, to love God and to have an interest in all that concerns His honor and glory, and the salvation of men's souls.

Is it then that they have lost their power, and that, now they are perfected in glory, God will no longer hear their prayers and accept their intercession? What more absurd! We have seen that it is not dead men that we invoke, when we invoke the Saints, but living men; and they are shorn of none of their powers by being beatified in Heaven, but rather have all their powers increased and multiplied a hundredfold. They were pleasing to God and had power with Him by their prayers, whilst yet they were struggling here upon earth: are they less pleasing to Him now because they are more perfect? Are they weaker because they have conquered and are crowned?

But it is their knowledge you doubt? You think they cannot see or know your wants. Whilst here upon earth, though separated by thousands of miles perhaps, yet the genius of man had invented means of communication whereby the requests of distant friends might be made known to one another; but now that they are in Heaven and released from the bonds of the body, has God no power to reveal to them what they desire to know? Whilst here upon earth, it was given to many of them to have visions of Heaven; but now that they are in Heaven, have they no means of having visions of earth? Whilst here upon earth, they "saw through a glass in a dark manner;" but now that they are in Heaven, they "see face to face" (1 Cor. 13: 12): nevertheless, though now they see and know God so perfectly, and God sees and knows all things—yea, and all things are in God—yet do they remain blind and ignorant? Whilst here upon earth, it was given to prophets to know the future; in Heaven, is it denied the Saints to know the present? Whilst here upon earth, Eliseus, though absent in the body, knew all that his servant Giezi was doing at a distance, and he gave the king of Israel information of all that passed in the Syrian camp (4 Kings 5: 6); but now that he is in Heaven and is no longer affected by all those accidents of time and space which so cramp and hinder the operations of our minds through the weakness of our bodies, has he no such power and is he incapable of receiving it?

Need we say more to expose the strange unreasonableness of Protestant opinion upon this subject? If anything is still wanting to the cogency of our arguments, it is to be found surely in the distinct testimony of Holy Scripture, which teaches us in one place that the Angels in Heaven know and rejoice at the sight of a penitent sinner upon earth; and in another, that in the next world we shall be "like the Angels" (Matt. 22: 30); so that it is hard to understand why any so-called Christians should take so perverse a pleasure in setting the narrowest possible limits to the knowledge and power of the glorified Saints. It is not thus that St. John speaks of them; he cannot find words to express their glory, or rather, he confesses that we do not know what it is, because it is so exceeding great; only what we do know goes far beyond anything we have yet said of them, for he says that they are "like God"—not like the Angels only, the Archangels, the Seraphim, the Cherubim, or the "spirits which are before His throne," but like to God Himself. "Dearly beloved, we are now the sons of God; and it hath not yet appeared what we shall be. We know that when He shall appear, we shall be like to Him, because we shall see Him as He is" (1 John 3: 2). To the Saints God has already appeared; they have entered into His presence, and rejoice in the Beatific Vision. Shall we deny them this slight resemblance to Him Whom they behold—the power of knowing all that concerns them here below? The Psalmist tells us that "they shall be inebriated with the plenty of Thy house, and Thou shalt make them drink of the torrent of Thy pleasure. For with Thee is the fountain of life, and in Thy light we shall see light" (Ps. 35: 10). But shall this light be insufficient for the discernment of their brethren's needs? They are the companions of Angels, "and are before the throne of God, and serve Him day and night," and "the smoke of the incense of the prayers of the Saints [i.e. of the faithful on earth] ascends up before God from the hand of the Angel" (Apoc. 7: 15; 8: 4). Are these prayers then known to the Angels, but unknown to the other citizens of the Heavenly Jerusalem, the "spirits of the just made perfect" (Heb. 12: 23)?

There is but one answer, I think, possible, to enable a man to escape from the conclusion to which all these considerations tend; and that is, that the invocation of Saints is forbidden in Holy Scripture. And accordingly this assertion is made, but it can never be proved. What the Bible and the Church forbid is the offering of supreme worship to any but God alone; and supreme worship does not consist in prayer but in sacrifice. Thus runs the Mosaic Law: "Thou shalt fear the Lord thy God and shalt serve Him alone;" and "He that sacrificeth to the gods shall be put to death, save only to the Lord" (Deut. 6: 13; Exod. 22: 20). And the Church speaking by the Council of Trent says the same thing: "Sacrifice may not be offered to the Saints, but only to God Who crowned the Saints; wherefore the priest does not say, I offer sacrifice to thee, O Peter, or Paul, but giving thanks to God for the victories they have won, he implores their help, that those whose memory we celebrate on earth would vouchsafe to intercede for us in Heaven;" and again, "We must pray to God to give us all good and deliver us from all evil, but to the Saints, as God's friends, to intercede for us with Him for the obtaining of all our petitions" (Sess. 22 c. 3, de Sacr. Mis.; Catech. Pars 4 c. 4 q. 3).

There is but one answer, I think, possible, to enable a man to escape from the conclusion to which all these considerations tend; and that is, that the invocation of Saints is forbidden in Holy Scripture. And accordingly this assertion is made, but it can never be proved. What the Bible and the Church forbid is the offering of supreme worship to any but God alone; and supreme worship does not consist in prayer but in sacrifice. Thus runs the Mosaic Law: "Thou shalt fear the Lord thy God and shalt serve Him alone;" and "He that sacrificeth to the gods shall be put to death, save only to the Lord" (Deut. 6: 13; Exod. 22: 20). And the Church speaking by the Council of Trent says the same thing: "Sacrifice may not be offered to the Saints, but only to God Who crowned the Saints; wherefore the priest does not say, I offer sacrifice to thee, O Peter, or Paul, but giving thanks to God for the victories they have won, he implores their help, that those whose memory we celebrate on earth would vouchsafe to intercede for us in Heaven;" and again, "We must pray to God to give us all good and deliver us from all evil, but to the Saints, as God's friends, to intercede for us with Him for the obtaining of all our petitions" (Sess. 22 c. 3, de Sacr. Mis.; Catech. Pars 4 c. 4 q. 3).

The very idea of a sacrifice implies that He to Whom it is offered is the Sovereign Lord and Master, that the thing offered is His, not only as to the use of it, but also as to its very substance and being, so that He has a right to change or destroy it according to His good pleasure; and for this reason things offered in sacrifice under the Old Law were either altogether destroyed, or where this was impossible, so changed as in fact to amount to destruction.

But prayer has no such meaning at all; prayer is only another name for asking, and all men daily ask one another for such assistance as they need and others are able to supply, whether in things temporal or spiritual: nor was it ever heard that God forbade or disapproved of such petitions. Once, indeed, the base flatterers of a heathen king procured an edict to be published, that no man should ask any petition of any god or man for thirty days, save only of himself, the king; and doubtless, God might, had He so willed, have made us similarly dependent upon Himself, and wholly independent of one another. But such has not been His action towards us either in civil or religious matters; on the contrary, He has knit us together in the closest bonds of fellowship and mutual dependence. More especially as Christians, He has made us members of one Body, which "being compacted and fitly joined together by what every joint supplieth, according to the operation in the measure of every part, maketh increase of the Body unto the edifying of itself in charity" (Eph. 4: 16). And the same charity which bids us supply the wants of those of our brethren upon earth who are in need, so far as we have the power, bids the Saints in Heaven to assist us, so far as they have the power; and their power is prayer.

We ask them to pray for us, not instead of praying for ourselves, but in addition to our prayers, and this, not because we mistrust God’s mercy, but because we mistrust our own unworthiness. God accepts prayer and answers it, according to the dispositions with which it is offered. He has Himself taught us to value especially the prayer of a just man, and He has even commanded such men at various times to intercede for sinners whom His justice would have otherwise punished. We know ourselves to be sinners, and therefore we seek help of just men, to intercede for us; as in matters of the world, when we wish to obtain some grace from one on whom we doubt whether we have sufficient claims to insure a favorable hearing, we try to avail ourselves of the friendly offices of another more nearly connected or more influential than we are, with him on whose will our petition really depends.

The Invocation of Saints then, and of Mary as their Queen, is so natural a thing in itself, and so manifestly in harmony with the teaching of God’s word and His government of the world, that we need say no more in its justification. It is necessary, however, that we should notice certain prayers which the Church sometimes uses both to our Blessed Lady and to other Saints, which seem to go beyond that power of intercession that we have been vindicating to them. Ordinarily, the burden of our prayers to all the Saints is Ora pro nobis—Pray for us; and in the Litanies, the difference between prayer to God and prayer to His Saints is very clearly brought out, and impressed upon the mind by the change from Miserere nobis—Have mercy upon us, following each address of the Three Persons of the Holy Trinity, to Ora pro nobis, after each name or title of a Saint. But there are some other hymns or antiphons addressed to our Blessed Lady, in which we do not scruple to ask Herself immediately for gifts which we more commonly ask Her to obtain for us, through Her intercession, from God; using therein a very pardonable license, such as men daily avail themselves in their conversation with one another, and which cannot possibly be misunderstood, where the first elements of Christian doctrine are once received and established.

Indeed, if it be an error, we may justly plead that Holy Scripture itself has betrayed us into it, since it frequently uses a similar ellipsis, attributing to men what is absolutely not theirs, but only in a certain sense, and under certain limitations. When the lame beggar, sitting at the Beautiful Gate of the Temple, asked alms of St. Peter, the Saint boldly answered, "Silver and gold I have none, but what I have I give thee. In the Name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, arise and walk" (Acts 3: 2). Had he therefore this power of himself, or did he by this form of speech imply a denial of his dependence on God? Again, St. Paul is not more guarded in his speech than St. Peter. He writes to the Romans (11: 13) that as long as he is the Apostle of the Gentiles, he will honor his ministry, "if by any means I may save some of them;" and to the Corinthians (1 Cor. 9: 22), "I became all things to all men, that I might save all." Nor is it of himself only that he so speaks; but he attributes similar power to all believers. "How knowest thou, O wife, whether thou shalt save thy husband? Or how knowest thou, O man, whether thou shalt save thy wife?" (1 Cor. 7: 16) Had any Catholic used such language now for the first time, about our Blessed Lady for example, and spoken of Her as having saved such and such a one, there would have not been wanting those who would have raised a cry of blasphemy against such a form of speech. Through a mistaken and ignorant zeal, men, more jealous of God's honor than He is of His own, would have said that such a mode of speaking robs Jesus of something that belongs exclusively to Himself. The Church is not more cautious than Holy Scripture; or rather, Holy Scripture and the Church teach precisely the same truth, when they speak in this way; and it is an important truth which they teach; but one which finds no place in the imperfect theological systems of man's invention. It would take us too far away from our subject fully to state and develop it here; nor is it necessary. The explanation already given is abundantly sufficient for "men of good will;" the captious and those that love contention refuse to be persuaded.

Indeed, if it be an error, we may justly plead that Holy Scripture itself has betrayed us into it, since it frequently uses a similar ellipsis, attributing to men what is absolutely not theirs, but only in a certain sense, and under certain limitations. When the lame beggar, sitting at the Beautiful Gate of the Temple, asked alms of St. Peter, the Saint boldly answered, "Silver and gold I have none, but what I have I give thee. In the Name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, arise and walk" (Acts 3: 2). Had he therefore this power of himself, or did he by this form of speech imply a denial of his dependence on God? Again, St. Paul is not more guarded in his speech than St. Peter. He writes to the Romans (11: 13) that as long as he is the Apostle of the Gentiles, he will honor his ministry, "if by any means I may save some of them;" and to the Corinthians (1 Cor. 9: 22), "I became all things to all men, that I might save all." Nor is it of himself only that he so speaks; but he attributes similar power to all believers. "How knowest thou, O wife, whether thou shalt save thy husband? Or how knowest thou, O man, whether thou shalt save thy wife?" (1 Cor. 7: 16) Had any Catholic used such language now for the first time, about our Blessed Lady for example, and spoken of Her as having saved such and such a one, there would have not been wanting those who would have raised a cry of blasphemy against such a form of speech. Through a mistaken and ignorant zeal, men, more jealous of God's honor than He is of His own, would have said that such a mode of speaking robs Jesus of something that belongs exclusively to Himself. The Church is not more cautious than Holy Scripture; or rather, Holy Scripture and the Church teach precisely the same truth, when they speak in this way; and it is an important truth which they teach; but one which finds no place in the imperfect theological systems of man's invention. It would take us too far away from our subject fully to state and develop it here; nor is it necessary. The explanation already given is abundantly sufficient for "men of good will;" the captious and those that love contention refuse to be persuaded.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com