Adapted from The Liturgical Year by Abbot Gueranger

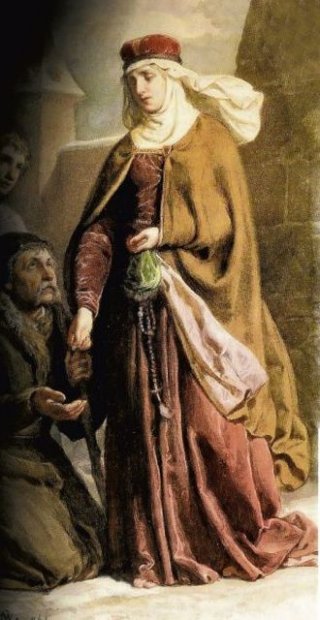

Saint Hedwig, Widow († 1243; Feast – October 16)

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the plateau of upper Asia poured down a fresh torrent of barbarians, more terrible than all their predecessors. The one fragile barrier, Ruthenia, which the Greco-Slavonian civilization could oppose to the Mongols, had been swept away by the first wave of the invasion; not one of the States formed under the protection of the Byzantine Church had any prospect for the future. But to the west of this land, which had fallen into dissolution before being conquered, the Roman Church had formed a brave and generous people—so that when the hour arrived, Poland was ready. The Mongols were already inundating Silesia, when, in the plains of Liegnitz, they found themselves confronted by an army of thirty thousand warriors, headed by the Duke of Silesia, Heinrich the Pious. The encounter was terrible; the victory remained long undecided, until at length, by the odious treason of some Ruthenian princes, it turned in favor of the barbarians. Duke Heinrich and the flower of the Polish knighthood were left dead upon the battlefield (April 8, 1241). But their defeat was equal to a victory. The Mongols retired exhausted, for they had measured their strength with the soldiers of the Latin Christianity.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the plateau of upper Asia poured down a fresh torrent of barbarians, more terrible than all their predecessors. The one fragile barrier, Ruthenia, which the Greco-Slavonian civilization could oppose to the Mongols, had been swept away by the first wave of the invasion; not one of the States formed under the protection of the Byzantine Church had any prospect for the future. But to the west of this land, which had fallen into dissolution before being conquered, the Roman Church had formed a brave and generous people—so that when the hour arrived, Poland was ready. The Mongols were already inundating Silesia, when, in the plains of Liegnitz, they found themselves confronted by an army of thirty thousand warriors, headed by the Duke of Silesia, Heinrich the Pious. The encounter was terrible; the victory remained long undecided, until at length, by the odious treason of some Ruthenian princes, it turned in favor of the barbarians. Duke Heinrich and the flower of the Polish knighthood were left dead upon the battlefield (April 8, 1241). But their defeat was equal to a victory. The Mongols retired exhausted, for they had measured their strength with the soldiers of the Latin Christianity.

It is Poland's happy lot, that at each decisive epoch in its history a Saint appears to point out the road to the attainment of its glorious destiny. Over the battlefield of Liegnitz shines the gentle figure of St. Hedwig, mother of Duke Heinrich the Pious. She had retired, in her widowhood, into the Cistercian monastery of Trebnitz founded by herself. Three years before the coming of the barbarians, she had had a revelation touching the future fate of her son. She offered her sacrifice in silence; and far from discouraging the young Duke, she was the first to animate him to resistance.

The night following the battle, she awoke one of her companions, and said to her: "Demundis, know that I have lost my son. My beloved son has fled from me, like a bird on the wing; I shall never see my son again in this life." Demundis endeavored to console her—no courier had arrived from the army, her fears were in vain. "It is but too true," replied the Duchess, "but mention it to no one."

Three days later the fatal news was confirmed. "It is the will of God," said St. Hedwig. "What God wills, and what pleases Him, must please us also." And rejoicing in the Lord: "I thank Thee, O my God," said she, raising her hands and eyes to Heaven, "for having given me such a son. He loved me all his life, always treated me with great respect, and never grieved me. I much desired to have him with me on earth, but I congratulate him with my whole soul, for that by the shedding of his blood he is united with Thee in Heaven, with Thee his Creator. I recommend his soul to Thee, O Lord my God." No less an example was needed to sustain Poland under the new task it had just accepted.

At Liegnitz it had raised up again the sword of Christendom, fallen from the feeble hands of Ruthenia. It became henceforth as a watchful sentinel, ever ready to defend Europe against the barbarians. Ninety-three times did the Tartars rush upon Christendom, thirsting for blood and rapine: ninety-three times Poland repulsed them at the edge of the sword, or had the grief to see the country laid waste, the towns burned down, the flower of the nation carried into captivity. By these sacrifices it bore the brunt of the invasion, and deadened the blow for the rest of Europe. As long as blood and tears and victims were required, Poland gave them unstintedly; while the other European nations enjoyed the security purchased by this continual immolation (Dom Guépin, S. Josaphat et l’Eglise grecque unie en Pologne, Intro.)

This touching page will be completed by the Church's story, where the part played by the saintly Duchess is so well brought forward:

St. Hedwig was illustrious for her royal descent, but still more for the innocence of her life. She was maternal aunt to St. Elizabeth, the daughter of the King of Hungary; and her parents were Berthold and Agnes, Duke and Duchess of Moravia (and Count and Countess of Andechs, her birthplace). From childhood she was remarkable for her self-control, for at that tender age she refrained from all childish games. At the age of twelve, her parents gave her in marriage to Heinrich, Duke of Poland (Silesia). She was a faithful and holy wife and mother, and brought up her children in the fear of God. In order the more freely to attend to God, she persuaded her husband to make with her a mutual vow of continency. After his death, she was inspired by God, Whose guidance she had earnestly implored, to take the Cistercian habit; which she did with great devotion in the monastery of Trebnitz. Here she gave herself up to divine contemplation, spending the whole time from sunrise till noon in assisting at the Divine Office and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. She utterly despised the old enemy of mankind (Satan).

St. Hedwig was illustrious for her royal descent, but still more for the innocence of her life. She was maternal aunt to St. Elizabeth, the daughter of the King of Hungary; and her parents were Berthold and Agnes, Duke and Duchess of Moravia (and Count and Countess of Andechs, her birthplace). From childhood she was remarkable for her self-control, for at that tender age she refrained from all childish games. At the age of twelve, her parents gave her in marriage to Heinrich, Duke of Poland (Silesia). She was a faithful and holy wife and mother, and brought up her children in the fear of God. In order the more freely to attend to God, she persuaded her husband to make with her a mutual vow of continency. After his death, she was inspired by God, Whose guidance she had earnestly implored, to take the Cistercian habit; which she did with great devotion in the monastery of Trebnitz. Here she gave herself up to divine contemplation, spending the whole time from sunrise till noon in assisting at the Divine Office and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. She utterly despised the old enemy of mankind (Satan).

She would neither speak of worldly affairs nor hear them spoken of, unless they affected the interests of God or the salvation of souls. All her actions were governed by prudence, and it was impossible to find in them anything excessive or disorderly. She was full of gentleness and affability towards all. She triumphed completely over her flesh by afflicting it with fasting, watching, and rough garments. She was adorned moreover with the noblest Christian virtues; she was exceedingly prudent in giving counsel; pure and tranquil in mind; so as to be a model of religious perfection. Yet she ever strove to place herself below all the nuns; eagerly choosing the lowest offices in the house. She would serve the poor on her knees and wash and kiss the feet of lepers, so far overcoming herself as not to be repulsed by their loathsome ulcers.

Her patience and strength of soul were admirable; especially at the death of her dearly beloved son, Heinrich Duke of Silesia, who fell fighting against the Tartars; for she thought rather of giving thanks to God, than of weeping for her son. Miracles added to her renown. A child that had fallen into a millstream and was bruised and crushed by the wheels, was immediately restored to life when the Saint was invoked. Many other miracles wrought by her having been duly examined, Pope Clement IV enrolled her among the Saints; and allowed her feast to be celebrated on the fifteenth of October, in Poland, where she is very greatly honored as a patroness of the country. Pope Innocent XI extended her Office to the whole Church, fixing it on the seventeenth of October. (In 1929 it was moved to the sixteenth of October, the seventeenth being appointed for the feast of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque.)

St. Hedwig, daughter of Abraham according to the Faith, thou didst imitate his heroism. Thy first reward was to find a worthy son in him whom thou didst offer to the Lord. Thy example is most welcome in this month, wherein the Church sets before us the death of Judas Machabeus. The death of thy son, Heinrich, was as glorious as his; but it was also a fruitful death. Of thy six children he alone, the Isaac offered and immolated to God, was permitted to propagate thy race. And yet what a posterity is thine, since all the royal families of Europe can claim to be of thy lineage! "I will make thee increase exceedingly, and I will make nations of thee, and kings shall come out of thee" (Gen. 17: 6). This promise, made to the Father of the faithful, is fulfilled once more on thy behalf, O St. Hedwig. God never changes; He has no need to make a new engagement; a like fidelity in any age earns from Him a like reward. Mayest thou be blest by all, O Mother of nations! Extend over all thy powerful protection; but above all others, by God's permission, may unfortunate Poland find by experience that thy patronage is never invoked in vain!

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Back to Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the plateau of upper Asia poured down a fresh torrent of barbarians, more terrible than all their predecessors. The one fragile barrier, Ruthenia, which the Greco-Slavonian civilization could oppose to the Mongols, had been swept away by the first wave of the invasion; not one of the States formed under the protection of the Byzantine Church had any prospect for the future. But to the west of this land, which had fallen into dissolution before being conquered, the Roman Church had formed a brave and generous people—so that when the hour arrived, Poland was ready. The Mongols were already inundating Silesia, when, in the plains of Liegnitz, they found themselves confronted by an army of thirty thousand warriors, headed by the Duke of Silesia, Heinrich the Pious. The encounter was terrible; the victory remained long undecided, until at length, by the odious treason of some Ruthenian princes, it turned in favor of the barbarians. Duke Heinrich and the flower of the Polish knighthood were left dead upon the battlefield (April 8, 1241). But their defeat was equal to a victory. The Mongols retired exhausted, for they had measured their strength with the soldiers of the Latin Christianity.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the plateau of upper Asia poured down a fresh torrent of barbarians, more terrible than all their predecessors. The one fragile barrier, Ruthenia, which the Greco-Slavonian civilization could oppose to the Mongols, had been swept away by the first wave of the invasion; not one of the States formed under the protection of the Byzantine Church had any prospect for the future. But to the west of this land, which had fallen into dissolution before being conquered, the Roman Church had formed a brave and generous people—so that when the hour arrived, Poland was ready. The Mongols were already inundating Silesia, when, in the plains of Liegnitz, they found themselves confronted by an army of thirty thousand warriors, headed by the Duke of Silesia, Heinrich the Pious. The encounter was terrible; the victory remained long undecided, until at length, by the odious treason of some Ruthenian princes, it turned in favor of the barbarians. Duke Heinrich and the flower of the Polish knighthood were left dead upon the battlefield (April 8, 1241). But their defeat was equal to a victory. The Mongols retired exhausted, for they had measured their strength with the soldiers of the Latin Christianity. St. Hedwig was illustrious for her royal descent, but still more for the innocence of her life. She was maternal aunt to St. Elizabeth, the daughter of the King of Hungary; and her parents were Berthold and Agnes, Duke and Duchess of Moravia (and Count and Countess of Andechs, her birthplace). From childhood she was remarkable for her self-control, for at that tender age she refrained from all childish games. At the age of twelve, her parents gave her in marriage to Heinrich, Duke of Poland (Silesia). She was a faithful and holy wife and mother, and brought up her children in the fear of God. In order the more freely to attend to God, she persuaded her husband to make with her a mutual vow of continency. After his death, she was inspired by God, Whose guidance she had earnestly implored, to take the Cistercian habit; which she did with great devotion in the monastery of Trebnitz. Here she gave herself up to divine contemplation, spending the whole time from sunrise till noon in assisting at the Divine Office and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. She utterly despised the old enemy of mankind (Satan).

St. Hedwig was illustrious for her royal descent, but still more for the innocence of her life. She was maternal aunt to St. Elizabeth, the daughter of the King of Hungary; and her parents were Berthold and Agnes, Duke and Duchess of Moravia (and Count and Countess of Andechs, her birthplace). From childhood she was remarkable for her self-control, for at that tender age she refrained from all childish games. At the age of twelve, her parents gave her in marriage to Heinrich, Duke of Poland (Silesia). She was a faithful and holy wife and mother, and brought up her children in the fear of God. In order the more freely to attend to God, she persuaded her husband to make with her a mutual vow of continency. After his death, she was inspired by God, Whose guidance she had earnestly implored, to take the Cistercian habit; which she did with great devotion in the monastery of Trebnitz. Here she gave herself up to divine contemplation, spending the whole time from sunrise till noon in assisting at the Divine Office and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. She utterly despised the old enemy of mankind (Satan).