Adapted from The Liturgical Year by Abbot Gueranger

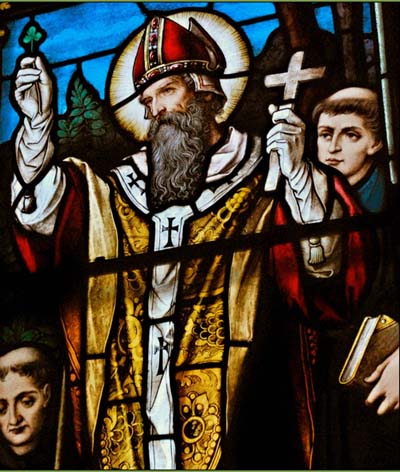

Saint Patrick, Bishop and Apostle of Ireland († 464; Feast – March 17)

Saint Patrick, according to his Confession (his autobiography), was born in a village called Bonaven Taberniae, which would appear to be the town of Killpatrick, on the mouth of the river Cluyd, in Scotland, between Dunbriton and Glasgow. He calls himself both a Briton and a Roman, or perhaps of a mixed extraction, and says his father was of a good family named Calphurnius, who not long after abandoned Britain, in 409. Some writers call his mother Conchessa, and say she was a niece to St. Martin of Tours. At fifteen years of age he committed a fault, which appears not to have been a great crime, yet was to him a subject of tears during the remainder of his life. He says that when he was sixteen, he lived "still ignorant of God," meaning of the devout knowledge and fervent love of God, for he was always a Christian: he never ceased to bewail this neglect, and wept when he remembered that he had been one moment of his life insensible of divine love.

Saint Patrick, according to his Confession (his autobiography), was born in a village called Bonaven Taberniae, which would appear to be the town of Killpatrick, on the mouth of the river Cluyd, in Scotland, between Dunbriton and Glasgow. He calls himself both a Briton and a Roman, or perhaps of a mixed extraction, and says his father was of a good family named Calphurnius, who not long after abandoned Britain, in 409. Some writers call his mother Conchessa, and say she was a niece to St. Martin of Tours. At fifteen years of age he committed a fault, which appears not to have been a great crime, yet was to him a subject of tears during the remainder of his life. He says that when he was sixteen, he lived "still ignorant of God," meaning of the devout knowledge and fervent love of God, for he was always a Christian: he never ceased to bewail this neglect, and wept when he remembered that he had been one moment of his life insensible of divine love.

In his sixteenth year he was carried into captivity by certain barbarians, together with many of his father's vassals. They took him to Ireland, where he was obliged to keep cattle on the mountains and in the forests, in hunger and nakedness, amidst snows, rain, and ice. Whilst he lived in this suffering condition, God had pity on his soul, and quickened him to a sense of duty by the impulse of a strong interior grace. The young man had recourse to Him with his whole heart in fervent prayer and fasting; and from that time faith and the love of God acquired continually new strength in his tender soul. He prayed often in the day, and also many times in the night, breaking off his sleep to return to the divine praises. His afflictions were to him a source of heavenly benedictions, because he carried his cross with Christ—that is, with patience, resignation, and holy joy.

St. Patrick, after six months spent in slavery under the same master, was admonished by God in a dream to return to his own country and informed that a ship was then ready to sail thither. He was at first refused passage, but God answered his prayers and the sailors, although pagans, called him back and took him on board. After three days' sail, they made land, probably in the north of Scotland: but wandered many days through deserted lands, and were a long while distressed for want of provisions, finding nothing to eat. St. Patrick had often spoken to the company about the infinite power of God: they therefore asked him why he did not pray for relief. Animated by a strong faith, he assured them that if they would address themselves with their whole heart to the true God, He would hear and assist them. They did so, and on the same day met with a herd of swine. From that time provisions never failed them, till on the twenty-seventh day they came into a country that was cultivated and inhabited.

Some years later he was again led captive; but recovered his liberty after two months. When he was at home with his parents, God manifested to him by visions that he destined him to the great work of the conversion of Ireland. He thought he saw all the children of that country from the wombs of their mothers stretching out their hands, and piteously crying to him for relief. (Historical documents indicate that Christianity had made some inroads into Ireland before St. Patrick; but the general conversion of the inhabitants of this island was reserved for our Saint.)

Some think he had travelled into Gaul (France) before he undertook his mission, and we find that, while he preached in Ireland, he expressed a great desire to visit his brethren in Gaul, and to see those whom he calls the saints of God, having been formerly acquainted with them. These probably include St. Martin of Tours and St. Germanus of Auxerre. It seems, from his Confession, that he received Holy Orders in his own country of Scotland. But he is said to have travelled to Rome to see Pope Celestine, from whom he received his mission, the apostolic benediction, and perhaps Episcopal Consecration.

In this disposition he passed into Ireland to preach the Gospel, where the worship of idols still generally reigned. He devoted himself entirely for the salvation of these barbarians, to be regarded as a stranger, to be condemned as the last of men, to suffer from the infidels imprisonment and all kinds of persecution, and to give his life with joy, if God should deem him worthy to shed his blood in His cause. He travelled over the whole island, penetrating into the remotest corners without fearing any dangers, and often visited each province. Such was the fruit of his preaching and suffering, that he consecrated to God, by Baptism, an infinite number of people, and labored effectually that they might be perfected in His service by the practice of virtue.

In this disposition he passed into Ireland to preach the Gospel, where the worship of idols still generally reigned. He devoted himself entirely for the salvation of these barbarians, to be regarded as a stranger, to be condemned as the last of men, to suffer from the infidels imprisonment and all kinds of persecution, and to give his life with joy, if God should deem him worthy to shed his blood in His cause. He travelled over the whole island, penetrating into the remotest corners without fearing any dangers, and often visited each province. Such was the fruit of his preaching and suffering, that he consecrated to God, by Baptism, an infinite number of people, and labored effectually that they might be perfected in His service by the practice of virtue.

He ordained everywhere clergymen, induced women to live in holy widowhood and continency, consecrated virgins to Christ, and instituted monks. Great numbers embraced these states of perfection with extreme ardor. Many desired to confer earthly riches on him, who had communicated to them the goods of Heaven; but he made it a capital duty to decline all self-interest, and whatever might dishonor his ministry. He took nothing from the many thousands whom he baptized, and often gave back the little presents which some laid on the altar, choosing rather to mortify the fervent than to scandalize the weak or the infidels. On the contrary, he gave freely of his own, both to pagans and Christians, distributed large alms to the poor in the provinces where he passed, made presents to the kings—judging that necessary for the progress of the Gospel, and maintained and educated many children whom he trained up to serve at the altar. He always gave till he had no more to bestow, and rejoiced to see himself poor, with Jesus Christ, knowing poverty and afflictions to be more profitable to him than riches and pleasures. The happy success of his labors cost him many persecutions.

A certain prince named Corotick—a Christian, though in name only, disturbed the peace of his flock. It appears that he reigned in some part of Wales, after the Britons had been abandoned by the Romans. This tyrant, as the Saint calls him, having made a descent into Ireland, plundered the country where St. Patrick had been just conferring Confirmation on a great number of Neophytes, who were yet in their white garments after Baptism. Corotick, without paying any regard to justice, or to the holy Sacraments, massacred many and carried away others, whom he sold to the infidel Picts or Scots. This probably happened at Easter or Pentecost. The next day the Saint sent the barbarian a letter by a holy priest whom he had brought up from his infancy, entreating Corotick to restore the Christian captives, and at least part of the booty he had taken, that the poor might not perish for want; but he was answered by railleries, as if the Irish could not be the same Christians as the Britons. The Saint therefore, to prevent the scandal which such a flagrant enormity gave to his new converts, wrote with his own hand a public circular letter. In it he calls himself a sinner and an ignorant man—for such is the humility of the Saints (most of all when they are obliged to exercise any acts of authority), contrary to the pompous titles which the world affects. He declares, nevertheless, that he is established Bishop of Ireland, and pronounces Corotick and the other parricides and accomplices separated from him and from Jesus Christ, Whose place he holds, forbidding any even to eat with them or to receive their alms, till they should have satisfied God by the tears of sincere penance, and restored the servants of Jesus Christ to their liberty. This letter expresses his most tender love for his flock, and his grief for those who had been slain, yet mingled with joy, because they reign with the Prophets, Apostles, and Martyrs. Historians assure us that Corotick was overtaken by the divine vengeance.

St. Patrick wrote his Confession, as a testimony of his mission, when he was old. It is solid, full of good sense and piety, expresses an extraordinary humility and a great desire of martyrdom, and is written with spirit. The author was perfectly versed in the Holy Scriptures. He confesses everywhere his own faults with a sincere humility, and extols the great mercies of God towards him in this world, Who had exalted him, though the most undeserving of men—yet, to preserve him in humility, afforded him the advantage of meeting with extreme contempt from others, that is, from the heathens. He confesses, for his humiliation, that among other temptations, he felt a great desire to see again his own country, and to visit the "saints" of his acquaintance in Gaul—but he dared not to abandon his people; and he says that the Holy Ghost had declared to him that to do so would be criminal. He tells us that a little before he had written this, he himself and all his companions had been plundered and laid in irons, for his having baptized the son of a certain king against the will of his father—but were released after fourteen days. He lived in daily expectation of such accidents, and of martyrdom; but feared nothing, having his hope as a firm anchor fixed in Heaven, and reposing himself with an entire confidence in the Almighty. He says that he had lately baptized a very beautiful young lady of high birth, who some days later came to tell him that she had been admonished by an angel to consecrate her virginity to Jesus Christ, that she might render herself the more acceptable to God. He gave God thanks, and she made her vows with extraordinary fervor six days before he wrote this letter.

St. Bernard and the tradition of the country testify that St. Patrick fixed his metropolitan See at Armagh. He established some other Bishops, as appears by his Council and other monuments. He not only converted the whole country by his preaching and wonderful miracles, but also cultivated this vineyard with so fruitful a benediction and increase from Heaven, as to render Ireland a most flourishing garden in the Church of God, and a country of Saints. And those nations, which had for many ages esteemed all others barbarians, did not blush to receive from the utmost extremity of the uncivilized or barbarous world—from Ireland, their most renowned teachers and guides in the greatest of all sciences, that of the Saints. (An example of this is the fact that archeological finds have proven that Irish missionaries achieved considerable success throughout Bavaria as early as the 6th century.)

St. Bernard and the tradition of the country testify that St. Patrick fixed his metropolitan See at Armagh. He established some other Bishops, as appears by his Council and other monuments. He not only converted the whole country by his preaching and wonderful miracles, but also cultivated this vineyard with so fruitful a benediction and increase from Heaven, as to render Ireland a most flourishing garden in the Church of God, and a country of Saints. And those nations, which had for many ages esteemed all others barbarians, did not blush to receive from the utmost extremity of the uncivilized or barbarous world—from Ireland, their most renowned teachers and guides in the greatest of all sciences, that of the Saints. (An example of this is the fact that archeological finds have proven that Irish missionaries achieved considerable success throughout Bavaria as early as the 6th century.)

Nennius, Abbot of Bangor in 620, in his History of the Britons, published by the learned Thomas Gale, says that St. Patrick took that name only when he was consecrated Bishop, being before called Maun; that he continued his missions over all the provinces of Ireland, during forty years; that he restored sight to many blind, health to the sick, and raised nine dead persons to life. He died and was buried at Down, in Ulster, around the year 464. His body was found there in a church of his name in 1185, and translated to another part of the same church. His festival is marked on the 17th of March in the Martyrology of St. Bede and in other sources.

The apostles of nations were all interior men, endowed with a sublime spirit of prayer. The salvation of souls being a supernatural end, the instruments ought to bear a proportion to it and preaching proceed from a grace which is supernatural. To undertake this holy function, without a competent stock of sacred learning and without the necessary precautions of human prudence and industry, would be to tempt God. But sanctity of life and the union of the heart with God, are a qualification far more essential than science, eloquence, and human talents. Many almost kill themselves with studying to compose elegant sermons, which flatter the ear yet reap very little fruit. Their hearers applaud their parts, but very few are converted. Interior humility, purity of heart, recollection, and the spirit and assiduous practice of holy prayer, are the principal preparation for the ministry of the word, and the true means of acquiring the science of the saints. A short devout meditation and fervent prayer, which kindle a fire in the affections, furnish more thoughts proper to move the hearts of the hearers, and inspire them with sentiments of true virtue, than many years employed solely in reading and study. St. Patrick, and other apostolic men, were dead to themselves and the world, and animated with the spirit of perfect charity and humility, by which they were prepared by God to be such powerful instruments of His grace, that they, by the miraculous change of so many hearts, planted in entire barbarous nations not only the Faith, but also the spirit of Christ. Preachers who have not attained to a disengagement and purity of heart, suffer the petty interests of self-love secretly to mingle themselves in their zeal and charity, and have reason to suspect that they inflict deeper wounds in their own souls than they are aware, and produce not in others the good which they imagine.

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Back to Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

Saint Patrick, according to his Confession (his autobiography), was born in a village called Bonaven Taberniae, which would appear to be the town of Killpatrick, on the mouth of the river Cluyd, in Scotland, between Dunbriton and Glasgow. He calls himself both a Briton and a Roman, or perhaps of a mixed extraction, and says his father was of a good family named Calphurnius, who not long after abandoned Britain, in 409. Some writers call his mother Conchessa, and say she was a niece to St. Martin of Tours. At fifteen years of age he committed a fault, which appears not to have been a great crime, yet was to him a subject of tears during the remainder of his life. He says that when he was sixteen, he lived "still ignorant of God," meaning of the devout knowledge and fervent love of God, for he was always a Christian: he never ceased to bewail this neglect, and wept when he remembered that he had been one moment of his life insensible of divine love.

Saint Patrick, according to his Confession (his autobiography), was born in a village called Bonaven Taberniae, which would appear to be the town of Killpatrick, on the mouth of the river Cluyd, in Scotland, between Dunbriton and Glasgow. He calls himself both a Briton and a Roman, or perhaps of a mixed extraction, and says his father was of a good family named Calphurnius, who not long after abandoned Britain, in 409. Some writers call his mother Conchessa, and say she was a niece to St. Martin of Tours. At fifteen years of age he committed a fault, which appears not to have been a great crime, yet was to him a subject of tears during the remainder of his life. He says that when he was sixteen, he lived "still ignorant of God," meaning of the devout knowledge and fervent love of God, for he was always a Christian: he never ceased to bewail this neglect, and wept when he remembered that he had been one moment of his life insensible of divine love. In this disposition he passed into Ireland to preach the Gospel, where the worship of idols still generally reigned. He devoted himself entirely for the salvation of these barbarians, to be regarded as a stranger, to be condemned as the last of men, to suffer from the infidels imprisonment and all kinds of persecution, and to give his life with joy, if God should deem him worthy to shed his blood in His cause. He travelled over the whole island, penetrating into the remotest corners without fearing any dangers, and often visited each province. Such was the fruit of his preaching and suffering, that he consecrated to God, by Baptism, an infinite number of people, and labored effectually that they might be perfected in His service by the practice of virtue.

In this disposition he passed into Ireland to preach the Gospel, where the worship of idols still generally reigned. He devoted himself entirely for the salvation of these barbarians, to be regarded as a stranger, to be condemned as the last of men, to suffer from the infidels imprisonment and all kinds of persecution, and to give his life with joy, if God should deem him worthy to shed his blood in His cause. He travelled over the whole island, penetrating into the remotest corners without fearing any dangers, and often visited each province. Such was the fruit of his preaching and suffering, that he consecrated to God, by Baptism, an infinite number of people, and labored effectually that they might be perfected in His service by the practice of virtue. St. Bernard and the tradition of the country testify that St. Patrick fixed his metropolitan See at Armagh. He established some other Bishops, as appears by his Council and other monuments. He not only converted the whole country by his preaching and wonderful miracles, but also cultivated this vineyard with so fruitful a benediction and increase from Heaven, as to render Ireland a most flourishing garden in the Church of God, and a country of Saints. And those nations, which had for many ages esteemed all others barbarians, did not blush to receive from the utmost extremity of the uncivilized or barbarous world—from Ireland, their most renowned teachers and guides in the greatest of all sciences, that of the Saints. (An example of this is the fact that archeological finds have proven that Irish missionaries achieved considerable success throughout Bavaria as early as the 6th century.)

St. Bernard and the tradition of the country testify that St. Patrick fixed his metropolitan See at Armagh. He established some other Bishops, as appears by his Council and other monuments. He not only converted the whole country by his preaching and wonderful miracles, but also cultivated this vineyard with so fruitful a benediction and increase from Heaven, as to render Ireland a most flourishing garden in the Church of God, and a country of Saints. And those nations, which had for many ages esteemed all others barbarians, did not blush to receive from the utmost extremity of the uncivilized or barbarous world—from Ireland, their most renowned teachers and guides in the greatest of all sciences, that of the Saints. (An example of this is the fact that archeological finds have proven that Irish missionaries achieved considerable success throughout Bavaria as early as the 6th century.)