Celebrated Sanctuaries of the Madonna

Fourth in a Series

In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

While some material covered in this and other chapters of Fr. Northcote's book have already been discussed in past articles (Our Lady of Loreto), Fr. Northcote adds many interesting facts, as well as his usual excellent apologetics. This is the book's longest chapter, so we present it in a somewhat more abridged form.

The Holy House of Loreto

"On a hillside on the east coast of Italy, at a distance of about three miles from the sea and eighteen miles south of Ancona, stands the city of Loreto. On the summit of the hill, towering far above the surrounding buildings, rises the magnificent cathedral church, with its great dome and campanile... From its great height and from its position, it may be seen, and the music of its bells is often heard, at a considerable distance out at sea. On entering the church, there is seen, beneath the dome, a singular rectangular edifice, of no great height, constructed apparently of white marble, and richly adorned with statues and sculptures. On entering this building, the contrast between the poverty of the interior—at least so far as the walls are concerned—and the richness of the marble exterior is astonishing. The walls, as seen from the interior, are the plain rough walls of a cottage, and evidently of great antiquity" (Loreto and Nazareth, W. A. Hutchison). This is the famous Holy House of Loreto, concerning which the following words appear in the Roman Martyrology under the date of December 10: In Piceno the Translation of the Holy House of Mary, the Mother of God, in which the Word was made Flesh; and in the Missal and Breviary, there are a proper Mass and Office commemorating the miraculous event which these words record.

"On a hillside on the east coast of Italy, at a distance of about three miles from the sea and eighteen miles south of Ancona, stands the city of Loreto. On the summit of the hill, towering far above the surrounding buildings, rises the magnificent cathedral church, with its great dome and campanile... From its great height and from its position, it may be seen, and the music of its bells is often heard, at a considerable distance out at sea. On entering the church, there is seen, beneath the dome, a singular rectangular edifice, of no great height, constructed apparently of white marble, and richly adorned with statues and sculptures. On entering this building, the contrast between the poverty of the interior—at least so far as the walls are concerned—and the richness of the marble exterior is astonishing. The walls, as seen from the interior, are the plain rough walls of a cottage, and evidently of great antiquity" (Loreto and Nazareth, W. A. Hutchison). This is the famous Holy House of Loreto, concerning which the following words appear in the Roman Martyrology under the date of December 10: In Piceno the Translation of the Holy House of Mary, the Mother of God, in which the Word was made Flesh; and in the Missal and Breviary, there are a proper Mass and Office commemorating the miraculous event which these words record.

"Now the Church," says St. Augustine (contra Faustum, lib. 32, c. 12), "makes an annual commemoration of those things which took place on certain days, and of which, by reason of their remarkable excellence, She deems it useful and necessary that the recollection should be observed by a festal celebration;" and again, the same learned Doctor says in another place (De Civ. Dei, 10, 3), "that we set apart and consecrate certain days to the commemoration of God’s benefits, in order that they may not, by the lapse of time, be lost sight of and forgotten." If then the Bishop of Hippo may be taken as a true exponent of the mind and motives of the Church in the institution of Her festivals, the translation of the Holy House of Loreto is an act of the loving-kindness of God, which it is both right and proper in itself, and also good for our souls' health, that we should not forget.

The ridicule of one half the world, and the devotion of the other half, has made everyone acquainted with the strange history of this translation, which is written in all the languages of Europe round the walls of the sanctuary; how the House in which our Blessed Lady was living in Nazareth when the Angel Gabriel was sent to Her from God, or rather the particular chamber of that House in which She then was, and in which the ineffable mystery of the Incarnation was accomplished; in which also Jesus was brought up and was subject to His parents; from which He went forth to the Jordan to be baptized by John before He began His public ministry; that this house, or chamber, was miraculously transported by the hands of angels, first from Galilee to Dalmatia (now part of Croatia), and afterwards from Dalmatia to Italy, towards the end of the thirteenth century, where it has ever since remained, an object of the deepest veneration to all the faithful.

Such is the event of which the Church of God solemnly preserves the memory by an annual commemoration, and which we must therefore conclude that She considers a benefit which demands our gratitude, and which is worthy of being held in our everlasting remembrance. Let us consider the matter for a moment from this point of view before we proceed to examine it in the light of history.

The whole history of this famous sanctuary may be said to be contained in a summary, or as in a promise or prophecy, in those words which the Church annually repeats in Her celebration of the Feast: "I will glorify the house of My majesty and the place of My feet" (Ant. ad Vsp.; Is. 60: 13; Ps. 131: 7). For certainly never was there a house so glorified, its name so made to resound from one end of the world to the other, as this humble chamber. "It is undoubtedly the most frequented sanctuary in Christendom," says an impartial witness (Dr. Stanley, writing in the 19th century prior to the Apparitions at Lourdes). "The devotion of pilgrims even on ordinary weekdays exceeds anything that can be witnessed at the holy places in Palestine, if we except the Church of the Holy Sepulcher at Easter. Every morning while it is yet dark, the doors of the Church are opened. A few lights round the sacred spot break the gloom, and disclose the kneeling Capuchins, who have been there through the night. Two soldiers, sword in hand, take their place by the entrance of the House, to guard it from injury. One of the hundred priests who are in daily attendance commences at the high altar the first of the 120 Masses that are daily repeated. The Santa Casa itself is then lighted, the pilgrims crowd in, and from that hour till sunset come and go in a perpetual stream. The House is crowded with kneeling or prostrate figures, the pavement round it is deeply worn by the passage of devotees, who, from the humblest peasant of the Abruzzi up to the King of Naples, crawl round it on their knees, while the nave is filled with bands of worshipers, who, having visited the sacred spot, are retiring from it backwards, as from some royal presence."

And whence comes all this—what is its cause? Precisely that spoken of by the prophet, because this Santa Casa is believed to be "the house of God's majesty and the place of His feet." Mount Sinai has ever been accounted a sacred spot, because the Lord once came down upon it with fire and in the darkness of a cloud, and gave to Moses there the two tablets of testimony, written with His own finger; but in the place of which we are now speaking, the Son of God "came down from Heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made Man;" "the Word was made Flesh, and dwelt among us." The temple of Solomon was wonderful and glorious and very holy, because of "the glory of the Lord which filled it;" but "great is the glory of this last house more than of the first" (Agg. 2: 10), by reason of the continued corporal and visible presence therein of Him Who was the "brightness of His Father's glory, and the very figure of His substance" (Heb. 1: 3). The city of Bethlehem in Juda became the subject of inspired praise and prophecy, because it was chosen to be the birthplace of the Son of God; but it was from Nazareth, and not from Bethlehem, that He received His Name, and "that was fulfilled which was said by the prophets, He shall be called a Nazarene" (Matt. 2: 6, 23). Or again, Mount Thabor witnessed the Transfiguration of Our Lord, Mount Calvary His Crucifixion, and Mount Olivet His Ascension; but with what place was He ever so intimately and so permanently connected as with this humble cottage, where He "came in and went out" among the children of men for so many years, before He was baptized by John in the Jordan?

"The Angel Gabriel was sent from God into a city of Galilee, called Nazareth, to a Virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph... and the Virgin's name was Mary" (Luke 1: 27). This was the beginning and the foundation of the "glory" of this house, the Annunciation of our Blessed Lady therein, and the consequent Conception within Her sacred womb of the Eternal Son of God. Presently She "rose up and went into the hill country," and was absent about three months, after which "She returned to Her own house" (Luke 1: 56); thereby again “glorifying” this humble cottage by the presence of Almighty God, since, where Mary was, there was God Incarnate. After the Flight into Egypt, "being warned in sleep, they retired into the quarters of Galilee," and once more returned to their ancient home; neither is there any reason to suppose that their residence there was any more interrupted, save only by the annual visits to Jerusalem, until the time when Jesus began His public ministry. Thus we see that the house of our Blessed Lady in Nazareth was the "house of God's majesty and the place of His feet" for the greater part of thirty years. As long as Jesus had any place "where to lay His head," that place was the house of His Mother in the city of Nazareth; it was there that "He was brought up" (Luke 4: 16). His neighbors and acquaintances spoke of Him as "the Son of Joseph of Nazareth," or more simply as "Jesus of Nazareth."

In a word then, Nazareth was preeminently "the city of Jesus," and the house of the Blessed Virgin in that city was His home, the earthly home of God Incarnate. And when once we have realized this simple, yet stupendous, fact, no exercise of Almighty power, however marvelous, whereby He may have been pleased in after ages to glorify it, ought to seem strange or improbable in our eyes.

It is a feeling natural to the human breast, that men should set a value on their paternal homes, and take pleasure in preserving them; whole societies have been formed, and still exist, with the avowed object of watching over the continual preservation of the house of some famous patriot or philosopher, some immortal bard or triumphant warrior, and the destruction of these memorials would have been resented as indicating a want of respect for the memory of the departed. Why then should it be counted a strange thing that the home of One Who was Perfect Man as well as God, should have been preserved by the almighty Hand of Him Who occupied it, through a series of more than 2000 years, so as still to remain amongst us even at the present day? Surely such preservation would have been naturally attempted—and there is nothing impossible in supposing it might have been effected, had such been the good pleasure of God—by merely human means, the devout care and watchfulness of the Christian flock. And to the Catholic mind, accustomed to realize the intimate communion which exists between the visible and the invisible world, the fact that this preservation has not really been accomplished without a miraculous interposition of Divine power, does not present even a momentary difficulty. A Catholic, believing rightly in the Incarnation of Our Lord Jesus Christ, would think it naturally probable, or certainly not improbable, that the sacred spot in which that stupendous mystery was wrought should have been preserved to the devotion of the faithful throughout all ages. Whether the means by which it was so preserved were natural or supernatural, or partly one and partly the other, would be merely a question of history, in the solution of which he would be guided only by the evidence, which might be alleged.

It is a feeling natural to the human breast, that men should set a value on their paternal homes, and take pleasure in preserving them; whole societies have been formed, and still exist, with the avowed object of watching over the continual preservation of the house of some famous patriot or philosopher, some immortal bard or triumphant warrior, and the destruction of these memorials would have been resented as indicating a want of respect for the memory of the departed. Why then should it be counted a strange thing that the home of One Who was Perfect Man as well as God, should have been preserved by the almighty Hand of Him Who occupied it, through a series of more than 2000 years, so as still to remain amongst us even at the present day? Surely such preservation would have been naturally attempted—and there is nothing impossible in supposing it might have been effected, had such been the good pleasure of God—by merely human means, the devout care and watchfulness of the Christian flock. And to the Catholic mind, accustomed to realize the intimate communion which exists between the visible and the invisible world, the fact that this preservation has not really been accomplished without a miraculous interposition of Divine power, does not present even a momentary difficulty. A Catholic, believing rightly in the Incarnation of Our Lord Jesus Christ, would think it naturally probable, or certainly not improbable, that the sacred spot in which that stupendous mystery was wrought should have been preserved to the devotion of the faithful throughout all ages. Whether the means by which it was so preserved were natural or supernatural, or partly one and partly the other, would be merely a question of history, in the solution of which he would be guided only by the evidence, which might be alleged.

What then is the evidence upon which a Catholic believes in the story of the translation of the Holy House? I suppose that the great majority of Catholics, if they were questioned upon this subject, would immediately reply that though they have never looked into the matter for themselves, yet they believe it to be true, because they have always been told so, and because they know that their Holy Mother the Church is far too wise and prudent to lend the sanction of Her name to tales of miraculous events without careful examination, and without at least probable grounds for the truth of Her decision. And who shall say that this answer would not be most just and reasonable? For life is not long enough for sifting and inquiring into everything, and there are a great many things which we must needs take, and which may safely be taken upon the credit of others. Moreover the Church is cautious in Her decisions on matters of this kind—so cautious, that we need not fear to trust Her when She breaks Her usual silence, and commends any particular miracle to the admiration of Her children by so solemn an act as the institution of a yearly festival for its commemoration. There are others, however, in the Catholic world... who would give a different answer; who would say... "I am now satisfied of its truth… upon the same grounds on which I believe any other fact in history about which there is a question—the arguments in favor of its truth seem to me infinitely stronger than any that can be urged against it, or (to state the same conclusion under another form) the difficulties in the way of believing it to be false seem to me infinitely stronger than the difficulties in the way of believing it to be true."

In the following pages then it is proposed to lay before the reader such an account of the evidence as we think abundantly warrants the conclusion which we have stated, with the earnest hope that some at least of our Protestant fellow-countrymen may be induced to study it with the same diligence and impartiality with which we have endeavored to write it. We know indeed that there are but too many amongst them, who, unwilling to allow to Almighty God the power of doing anything whose reasonableness and utility cannot be established satisfactorily to their own understandings, consider themselves privileged to reject the whole story at once and without any examination whatever, as manifestly absurd and false; men who do not scruple to trust to this prejudgment of theirs as though it were necessarily infallible, and more than sufficient to counter-balance the opposite belief of millions of Catholics of every nation under Heaven, including hundreds of thousands of men of learning and ability who have believed, not on tradition, but on their own personal conviction. For such as these it is useless to write; for even though it were possible to make the proof of the history as clear and cogent as that of a mathematical demonstration, yet they would still continue to speak of it as though it were an exploded fable, a matter on which there could not possibly be any difference of opinion, and which deserves to be remembered only that it may be quoted in controversy, as a striking specimen of the infamous "impositions of priestcraft," and the "ignorant superstitions" of Catholics generally...

When we come to examine in detail the evidence that can be alleged for the translation of the Holy House, there seem to be three points to which our attention should be especially called, or rather three principal epochs into which our inquiry will naturally divide itself. First, the evidence there is for supposing that the house of the Blessed Virgin, which it is certain from Holy Scripture was once in Nazareth, remained there undestroyed during more than 1200 years; secondly, the evidence for the fact of its translation from Nazareth into Dalmatia; and thirdly, the evidence for its translation from Dalmatia into Italy. We propose to arrange our remarks as far as may be, according to this triple division, as being the most simple and convenient.

To begin, then, with the important question of the preservation of our Blessed Lady's house in Nazareth during the first twelve centuries of the Christians era. It is an old tradition (Adrichomius, Teatrum Terrae Sanctae), and conformable to everything we know of the habits of the early Christians, that this building, which had been consecrated by the continual presence of the Incarnate Son of God during a space of nearly thirty years, had been set aside even by the Apostles themselves to sacred uses; but be this as it may, ancient authorities tell us, that when the Empress St. Helena visited the Holy Land, she raised churches and oratories in all the spots which had witnessed the principal events of Our Lord's life in Palestine (Paulinus, Ep. xi ad Severum—in which he specifically mentions the Incarnation), and we cannot suppose that she overlooked this one spot in particular, where the first foundations, as it were, of our salvation had been laid. Eusebius indeed dwells especially on the magnificence of the churches she built at Bethlehem and Mount Olivet, as the scenes of the Nativity and the Ascension; but Nicephorus Callistus gives us particulars of many other churches also, and especially says that she "went down to Nazareth, and having found there the House of the Angelic Salutation, built a very beautiful church to the Mother of God" (Niceph. H. E. viii, 30). Of course, testimony of this (later) author is not so satisfactory as that of Eusebius (a contemporary) would have been; nevertheless "a tradition is not upset," says Pope Benedict XIV, "by the circumstance that there are no contemporary monuments of the fact handed down, when other later monuments of great weight are not wanting." Indeed it has been well said that the opposite assumption—that no tradition is ancient or trustworthy whose continuous existence is not vouched by contemporary documents—expunges half the history of the world in one blow.

In the seventh century we have the evidence of Adamnan (De Locis Sanctis ii, 6), which is repeated also by our own Venerable Bede (De Loc. Sanc. c. 16, t. iv), that there were two churches in Nazareth; one erected where formerly had stood the house in which Our Lord was brought up as a child; the other where the house had been in which the Angel Gabriel came to the Blessed Mary. And some writers, who deny the truth of the alleged miraculous translation of the House to Loreto in the thirteenth century, ground their denial in great measure upon the language of these writers: they acknowledge that it was in existence in the days of St. Helena in the fourth century, but they say that she destroyed it, and built a church in its stead. We may accept the former part of their statement, but reject the latter; for although it is true that St. Helena built a church there, it by no means follows that she would therefore have destroyed the house. (Image at left: Grotto of the Annunciation Church in Nazareth; Foundations of the Holy House.)

In the seventh century we have the evidence of Adamnan (De Locis Sanctis ii, 6), which is repeated also by our own Venerable Bede (De Loc. Sanc. c. 16, t. iv), that there were two churches in Nazareth; one erected where formerly had stood the house in which Our Lord was brought up as a child; the other where the house had been in which the Angel Gabriel came to the Blessed Mary. And some writers, who deny the truth of the alleged miraculous translation of the House to Loreto in the thirteenth century, ground their denial in great measure upon the language of these writers: they acknowledge that it was in existence in the days of St. Helena in the fourth century, but they say that she destroyed it, and built a church in its stead. We may accept the former part of their statement, but reject the latter; for although it is true that St. Helena built a church there, it by no means follows that she would therefore have destroyed the house. (Image at left: Grotto of the Annunciation Church in Nazareth; Foundations of the Holy House.)

St. Cecilia's house in Rome was given to the Christians and converted into a church; but the room which was the special scene of the virgin-martyr's sufferings and triumph, remained unaltered, and may be seen to this day. In like manner the place of infamy in which St. Agnes was exposed became a church; but the sacred interest which attached to those particular chambers caused them to be retained as they still are. The Mamertine prisons in the same city, in which St. Peter was detained; the cave of St. Benedict at Subiaco; the little church of St. Francis of Assisi; and a hundred other places that might be named, are all instances of the same principle. In all these places the piety of Christians has caused churches to be built with a greater or less degree of magnificence, but always without destroying those particular spots which were in a more special manner the object of their devotion; and why should not St. Helena have done the same here also? Even if history were altogether silent upon the subject, there would still have been a strong a priori probability in favor of those who have maintained that while the first Christian Empress raised a temple (as it was only natural that she should) in this most holy place, yet she was careful not to destroy that part of it which may justly be called the holy of holies—that chamber in which the Word was made Flesh.

John Phocas, a Greek priest, who visited the Holy Land in the year 1185—that is to say, a whole century before the alleged translation—and wrote an account of his travels, expressly mentions, in his description of this church—the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth—that on the left-hand side, near the high altar, there is "an opening, through which you descend by a few steps into the ancient house of Joseph, in which the Archangel made the joyful annunciation to the Blessed Virgin on Her return from the fountain" (Apud Acta SS. Bolland. Maii 2, tom. ii). We need not allow ourselves to be perplexed because this author happens to have called it the house of Joseph instead of the house of Mary, for of course it might truly be called the house of either indifferently; neither again are we at present concerned with the Oriental tradition to which he alludes as to the occupation of our Blessed Lady at the precise moment of the Angel's visit; his testimony is quoted in this place, only for the sake of the information which he gives as to the position of the spot which was the scene of the Annunciation with reference to the general plan of the whole church; and upon this point his testimony is most important. Our Blessed Lady's chamber, the sancta sanctorum of this church, was somewhat below the level of the rest of the building; it was necessary to go down to it by a few steps; it was also on one side of the main building. The reader will see at once that this circumstance (which in a town like Nazareth, built on the brow of a hill (Luke 4: 29), was a very natural one) lends the strongest confirmation to what we have said as to the possibility of St. Helena's church having included within itself, and not destroyed, the particular spot to which she desired to do honor; in fact, it is not too much to say that it distinctly proves it.

Of course, this is not the only writer from which we derive our knowledge of the interior of Our Lady's church in Nazareth; on the contrary we might quote a similar description from the pens of innumerable other travelers; such as Zuallard the Belgian, who accompanied the Baron de Marode in his visit to those parts in the year 1586, who says that "to go to the place where the Annunciation was made, which is below the level of the church, you descend twelve steps... There are the foundations of the house of Joseph, in which it is said that Our Lord was brought up when He was a child; but the remainder of the house has been miraculously transported by angels into Christendom, and is at present in Italy, in a city called St. Mary of Loreto" (Il devotissimo Viaggio di Gerus, lib. iv, p. 281, Romae 1587)... We have chosen the testimony of the Greek, however, because it is the only one that belongs to a date anterior to that of the alleged removal of the house, so that any coincidence which may be discovered between it and the miraculous history that is to follow is especially valuable. On the whole therefore it is perfectly certain that there is not the slightest inconsistency in supposing St. Helena to have built a church in honor of the Annunciation, and in the place where it happened, and yet to have left the chamber itself undisturbed; and for many reasons which the reader will presently recognize, it is important that this point be clearly established.

Grotto of the Annuncation (viewed from above).

Before resuming the thread of our history, it will be well to make yet another remark upon the evidence of St. Adamnan and St. Bede. They speak, as we have seen, of two churches in Nazareth—one built where the Angel appeared to Mary, the other where the house had been in which Our Lord was brought up as a child; and as both of these high prerogatives are usually claimed for the House of Loreto, it is necessary that we should observe that the second church appears to have been built on the place where St. Joseph carried on his business as a carpenter, and in which therefore Our Lord may be said to have been brought up quite as truly as in His Mother's dwelling-house. The Père Geramb tells us that it is at a distance of 130 or 140 paces from the first church, and that it still retains the name of St. Josph's workshop. I only mention this for the sake of removing a difficulty which otherwise might perplex those who have an opportunity for consulting the original authorities to which we refer.

About a hundred years later than St. Bede, the church is again spoken of by the biographer of St. Willibald, the first Bishop of Eichstätt, who lived A.D. 775; or rather by the author of his "Itinerary," supposed by some to be his sister (St. Walburga, or rather, by a nun of her monastery named Huneberc). "Having performed their devotions," it says, "they went on to Galilee, to the place where Gabriel first came to Holy Mary. Here there is now a church, in the village of Nazareth. And for this church Christians have often paid money to the heathens, to prevent them from executing their purpose of destroying it" (Apud Canis. Thesaur. ii, p. 110). William Archbishop of Tyre tells us that it was visited in the twelfth century by Tancred, and endowed by him with such magnificence, that it became the metropolitan church of all Galilee.

A hundred years later still, it was watered by the tears of St. Francis of Assisi; and in the same century by those of St. Louis of France. The biographer of this royal Saint has recorded that, as soon as he came in sight of Nazareth, he dismounted from his horse and kissed the ground; that he then went on to "the place of the Incarnation," heard Mass and received the Holy Eucharist there, "in the very chamber where the Virgin Mary, Our Lady, was saluted by the Angel, and declared the Mother of God;" after which he heard another Mass celebrated "at the high altar of the Church" by Odo the Cardinal-Bishop of Frascati and Legate of the Holy See (Storia di S. Luigi IX del Pietro Mattei, p. 171, lib. iii, Venice 1628). Nothing can be more precise and distinct than this testimony, which belongs to the autumn of 1253, six months before St. Louis left the Holy Land to return to his own kingdom, and forty years before the alleged translation of the chamber from Galilee to Dalmatia.

Church of the Annuncation (19th century depiction).

It happens however that it is just during this interval of forty years that some critics think they can find the surest proof of the destruction of the sacred building, and therefore of the nonentity of its subsequent translation. In the year 1263—that is, ten years after this visit of St. Louis—Pope Urban IV wrote him a letter, in which he complains that the enemy have "not only seized upon that venerable church in Nazareth, beneath whose roof the Virgin of Virgins received the salutation of the Angel and conceived of the Holy Ghost, but have even destroyed it; their wicked and sacrilegious ministers have in their fury levelled it to the very ground and altogether destroyed it." This language is certainly very strong and plain; yet even though every word of it were strictly and literally true, it would still be possible that the chamber itself, ipsissimus locus Incarnationis, had survived the wreck, because, as we have already seen, it was upon a lower level, and on one side of the main building; just as if anyone had said of the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli at Assisi, that it was destroyed by the earthquake of 1832 (as it was), and yet the chapels, which are the principal objects of devotion there, escaped unhurt. However there is good reason to suppose that Pope Urban had received a somewhat exaggerated account of the mischief that had been done—for the infidels were rapidly regaining the ground they had lost, and it was only natural, therefore, that those Christians who still remained in the Holy Land should send to Europe, and especially to Rome, as sad a tale as they could, so that the flame of Christian zeal might be once more enkindled, and the chivalry of France and England once more persuaded to come forth and do battle to rescue the holy places. And there is some evidence that it really was so; for first there is an ancient tradition (P.F.Q. di Lodi, Historica, Theologica et Moralis Terrae Sanctae Elucidatio, tom. ii lib. vii c. 3 § 3), that when the main body of the Crusaders had abandoned the Holy Land, the Archbishop of Nazareth, together with the larger portion of his flock, made their peace with the Turks at the price of apostasy, and that it was on this occasion that the Church of the Annunciation was pulled down; only the northern part of it was preserved, because to that side was attached the Episcopal residence, the same which was afterwards occupied as a Franciscan monastery. Now since, as we have seen, it was precisely under this part that the Santa Casa lay, it is only reasonable to conclude that this also need not have been destroyed.

Secondly, William de Bandensel, a German nobleman, and a Knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, who traveled in those parts with a private chaplain and a numerous retinue about the year 1336, in speaking of this place, says only that there had been here a large and beautiful church, but that it was now almost destroyed (Canisii 'Thesaurus Monum.' tom. iv). If, after more than seventy years of unavoidable neglect on the one hand, and of exposure to the wanton injuries of malicious enemies on the other, a traveler could use such moderate language as this, we may be sure that the words of Pope Urban's letter do not really denote quite as much as at first sight they might seem to imply... certainly we need not waste time in proving that a church that was "almost destroyed" in 1336 cannot have been "altogether destroyed" in 1263; and that it is quite possible, therefore, that a particular portion of that church which we know to have been in existence in 1253, may also have been in existence in 1291, which is the date of the alleged translation.

We need not hesitate, therefore to pass on to an examination of the second object of our inquiry—the evidence for its translation from Galilee into Dalmatia; but first we would just notice by the way how exactly the date of this event tallies with the known history of the times. I mean that, supposing it to have been God's will that the House should be preserved from destruction, we cannot conceive a more fitting time, or even, if we may use such an expression, a more necessary time, for His immediate interference in order to effect this purpose, than that which tradition has assigned. It is said to have taken place on May 10, 1291, just when the Christian rule in Palestine had received its death-blow by the fall of Acre, its last bulwark, on April 18 in that very year. Henceforward the Christian sanctuaries were exposed to all the injuries which the most inveterate malice could devise, and the most unlimited license execute; and as to the nature and extent of those injuries, one may form a tolerably correct idea from the letter of Pope Urban IV, which has already been quoted. If then it was in the counsels of Divine Wisdom that the chamber, in which the Second Person of the Most Holy Trinity took upon Himself the nature of man in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, should be preserved to all succeeding ages as a monument to confirm their faith and excite their devotion towards that most adorable mystery, the interposition of a supernatural power seems now to have been imperatively called for...

We need not hesitate, therefore to pass on to an examination of the second object of our inquiry—the evidence for its translation from Galilee into Dalmatia; but first we would just notice by the way how exactly the date of this event tallies with the known history of the times. I mean that, supposing it to have been God's will that the House should be preserved from destruction, we cannot conceive a more fitting time, or even, if we may use such an expression, a more necessary time, for His immediate interference in order to effect this purpose, than that which tradition has assigned. It is said to have taken place on May 10, 1291, just when the Christian rule in Palestine had received its death-blow by the fall of Acre, its last bulwark, on April 18 in that very year. Henceforward the Christian sanctuaries were exposed to all the injuries which the most inveterate malice could devise, and the most unlimited license execute; and as to the nature and extent of those injuries, one may form a tolerably correct idea from the letter of Pope Urban IV, which has already been quoted. If then it was in the counsels of Divine Wisdom that the chamber, in which the Second Person of the Most Holy Trinity took upon Himself the nature of man in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, should be preserved to all succeeding ages as a monument to confirm their faith and excite their devotion towards that most adorable mystery, the interposition of a supernatural power seems now to have been imperatively called for...

It is said then—and be it remembered that it is so far said by the Catholic Church as that She permitted an addition to that effect to be inserted in the Roman Martyrology under the date of December 10 (by a decree of the Congregation of Rites, August 31, 1669), and a lesson embodying the whole history to be added to the Office provided for that day in the Roman Breviary (i.e., as a particular feast—yet found in nearly all breviaries, approved by a similar decree, September 16, 1699)—that the House of our Blessed Lady in Nazareth was miraculously translated by the ministry of angels from Galilee to Dalmatia in the month of May, 1291, and that it was again removed and transported into Italy on December 10, 1294. Now the first idea that strikes one in considering the authenticity of this history is this: supposing it not to be true, how exceedingly improbable it is that it should ever have been invented! Let us concede for a moment that it was possible, when first the House appeared at Loreto, to invent some story of its having been brought there by a miracle; yet what could have induced the inventors to pretend that it was brought from a place in Dalmatia, rather than immediately from Galilee itself? This would not only have thrown an apparent doubt upon its genuineness, upon its being really what they asserted it to be, the House in which Our Lord had been conceived in Nazareth, but also it would have afforded additional facility for detecting the imposture; since it was far easier to go or to send to Dalmatia and ascertain the truth of the report, than to run the risk of being murdered or imprisoned by the Turks in the course of a dangerous pilgrimage to Palestine.

But in the next place, even if we allowed that for some inconceivable reason the inventors of the story were stupid enough to clog it with this most clumsy and untoward circumstance, yet how did they persuade the people of Dalmatia to lend themselves to the fraud? The people of Loreto, we will imagine, were so proud of the high honor which would attach to them as being supposed to be the chosen guardians of a very sacred treasure, that they were not likely to inquire too minutely into the history upon which such a supposition was based; all inconvenient criticism would be prevented by a very natural and pardonable vanity. But how came the natives of Dalmatia to exercise the same forbearance without the same motive, or rather in spite of every motive naturally urging them to the most severe and rigid scrutiny?

The sacred House had been transported from the Holy Land (so said the story), because that land had fallen into the hands of the enemies of the Christian Faith, who would insult and perhaps destroy it; it had been brought into a Christian land, to an eminence between the towns of Tersatto and Fiume (about sixty miles south of Trieste, on the eastern side of the Adriatic Gulf), and it remained there for the space of three years and a half, when it was again removed and carried into Italy. Did not this second removal seem to speak the same language as the first—to cast an imputation upon the character of those from whom the House was taken? To imply that they were not worthy of it any more than the Turks had been? We are not presuming ourselves to pry into the hidden counsels of God, and to assign this as the real motive of the second translation; but we say that this is what would naturally occur to any man as soon as he heard of it. Nay more, this is what the earliest historians of the sanctuary actually said; and we ask whether the Dalmatians were likely, without good reason, to acknowledge a fact which seemed so manifestly to redound to their discredit, and silently to acquiesce in a tradition which could not fail to be so interpreted by the great majority of those to whose knowledge it might be brought?

Surely it does not require any intimate knowledge of human nature to feel confident that such a tradition could never have taken deep root among a people unless it had been founded on fact. And yet not only is the tradition recorded by some of their own authors; not only was its memory preserved by a church, in imitation of the original House, built upon the spot from which it had been removed, with an inscription engraved upon its walls declaring that "this is the place where was formerly the most Holy House of our Blessed Lady, which is now at Recanati" (Rainaldi, Annales ad A.D. 1294); not only has it been perpetuated by the establishment, by Pope Gregory XIII, in Loreto itself, of a college, which still remains, for students from the Illyrian nation (Dalmatia); not only, I say, is the existence of such a tradition attested in these and other ways, but also still more unequivocally (because more popularly) by the fact of innumerable pilgrims having come year after year, century after century, from that part of Dalmatia to the sanctuary of Loreto, there to lament over their heavy loss, and to entreat our Blessed Lady to return to them.

Modern Shrine of Our Lady of Loreto in Croatia—"World's Largest Loreto Statue."

"I was sitting in the Church of Loreto, hearing confessions," writes Fr. Riera in the year 1559, "when I heard a most unusual disturbance and the sound of much crying and groaning; I came out of the confessional to inquire into its cause, and there at the threshold of the church I saw kneeling from four to five hundred Dalmatians—men, women and children—divided into different companies, each company under the direction of a priest, and all crying out with sighs and tears, 'Return, return to us, O Mary! O most Holy Mary, return to Fiume!' Touched with compassion for their distress, I drew near to a venerable priest who was amongst them, and asked the cause of their sorrow. With a deep sigh he answered, 'Ah! they have only too much cause;' and again he repeated with still greater energy, 'Return, return to us O Mary!' When they advanced within the church, and arrived where they could see the entrance to the Holy House, their cries and sobs grew yet louder. I tried as well as I could to assuage their grief, and to direct them to look for consolation from Heaven, but the old man interrupted me and said, 'Suffer them to weep, Father; their lamentations are only too reasonable; that which you possess was once ours.' At last I was obliged to exert my authority to restore order and enforce silence; and, indeed, their prayers were so earnest, that I could not but fear that God would listen to their request." He tells us that this was only in an extraordinary degree a specimen of what he had witnessed every year that he was at Loreto, and had happened (so he was told) every year from time immemorial—persons from Fiume and its neighborhood, only not usually in such great numbers, coming over the sea to visit the Holy House of Loreto, and to entreat the Blessed Virgin to restore it to them.

The testimony of Fr. Torsellino forty years later, that is, 300 years after the supposed loss, is equally distinct; he says that "these pilgrims came every year in shoals, and quite as much to lament over their own loss, as to do honor to the House of Mary." Fr. Renzoli repeats the same at the end of the next century; and we learn from the Archdeacon Gaudenti that it still continued in the year 1784.

Now, although of course the "impositions of priestcraft" are quite as possible on one side of the Adriatic as on the other, still it is worthwhile to wonder what kind of motives could it possibly have appealed to, what passions of the human heart could it have enlisted on its side, when it first devised this "deceit" and it imposed it upon the people. For let "priestcraft" be as clever and as potent as the most ignorant or the most zealous Protestant can imagine, still, as long as it is only natural—not miraculous, as long as it is something short of magic, it can only influence others by means of the ordinary motives and principals of human action, roused into activity by false appearances perhaps, and aiming at wrong ends, but still the same motives. But which of these motives can be imagined in the present instance powerful enough to have produced the result that has been described? Not vain-glory—for, as has been already said, the story was manifestly to the general discredit of the inhabitants of that country, whether clergy or laity; not sordid interest—for how could it profit the priests of Fiume and Tersatto that their flock should go on pilgrimage and make offerings to the distant shrine of Loreto? Not a mere love of the marvelous—for this might have been quite as effectually gratified by applying the same story to the shrine which they still had at home; not even a desire to gain spiritual privileges and indulgences—for these had been bestowed with a most generous hand upon their own sanctuary by many successive Popes, from Urban V in the 14th century down to Clement XI at the beginning of the 18th. In a word, it is difficult to conceive what could have persuaded the Dalmatians to depreciate a church of their own country, singularly enriched both temporally and spiritually, to confess that it was a mere memorial and imitation of a marvelous original which they had once had and now had lost, and to put themselves to great inconvenience to go and visit that lost original elsewhere, excepting only a deep and settled conviction that the history of the two churches was precisely such as it is commonly supposed to be. Is it possible that such a conviction could have been created, so as to become a living and powerful source of action in the mind of a whole people, by anything short of the truth? At any rate, it is impossible to deny that the Dalmatian tradition furnishes reasonable evidence of as much as this—that a building which was believed to be the House in which the Word was made Flesh in Nazareth, was once in their country, and is now in Italy...

The tradition goes on to say that at the end of about three and a half years after its original appearance in Dalmatia, that is, on December 10, 1294, the Holy House was miraculously transported across the sea, and set down in a forest about a mile from the shore, on the opposite coast of Italy (this forest belonging to one whose name was Laureta—hence Loreto); that it was visited there by innumerable persons, but that wicked men took advantage of the vicinity of the wood to conceal themselves in it and to commit acts of violence upon the pilgrims, so that it was very soon removed to an eminence at some little distance; here also it attracted the public devotion so powerfully, that the two brothers to whom the hill belonged soon began to quarrel as to the proper way to dispose of the numerous offerings which were made; and finally, after another short interval, it was again removed, without human help, to a spot on the highway of Recanati, where it has ever since remained. We have to enquire whether this story is a true narration of facts, or merely a fabulous invention.

Here again, the first reflection which occurs to a thoughtful and candid mind is this—if the story be false, why did the inventor make it so extremely clumsy? We presume he wished it to be believed, and did his best therefore to secure its being believed; why then did he multiply the chances of detection by pretending three translations instead of one? How had he not the wit to see that three translations within the distance of a few miles and in the space of a single year, wrought by superhuman agency, would be looked upon with most keen suspicion by everybody jealous for the honor and glory of God? Would it not seem, if we may be allowed to use such language with reverence, as if Almighty God had not from the first thoroughly known His own mind, what He proposed to do with the House, or as if He had not foreseen, or had been unable to provide against, the inconveniences and dangers to which it proved to be exposed in each of its successive resting-places? Surely everybody must admit that the whole story is as far from being probable... as far as being likely to deceive people and to win their uninquiring assent by its plausibility... as anything that could possibly be imagined. And yet the people were "deceived;" the story has gained universal credence; and the spots which were consecrated by the merely temporary presence of the sacred building have always been known and pointed out.

Here again, the first reflection which occurs to a thoughtful and candid mind is this—if the story be false, why did the inventor make it so extremely clumsy? We presume he wished it to be believed, and did his best therefore to secure its being believed; why then did he multiply the chances of detection by pretending three translations instead of one? How had he not the wit to see that three translations within the distance of a few miles and in the space of a single year, wrought by superhuman agency, would be looked upon with most keen suspicion by everybody jealous for the honor and glory of God? Would it not seem, if we may be allowed to use such language with reverence, as if Almighty God had not from the first thoroughly known His own mind, what He proposed to do with the House, or as if He had not foreseen, or had been unable to provide against, the inconveniences and dangers to which it proved to be exposed in each of its successive resting-places? Surely everybody must admit that the whole story is as far from being probable... as far as being likely to deceive people and to win their uninquiring assent by its plausibility... as anything that could possibly be imagined. And yet the people were "deceived;" the story has gained universal credence; and the spots which were consecrated by the merely temporary presence of the sacred building have always been known and pointed out.

Of course, if the story is true, all these difficulties instantly disappear—facts are stubborn things, and when they are proved, supersede the necessity of arguments. And so, if the triple translation was a fact, it is not strange that it should have been believed; but if, on the other hand, it was a human invention, we can neither comprehend the stupidity of him who devised it, nor the simplicity of those who received it. We may also still further observe that, supposing the triple translation to be true, we can see at once what a powerful effect it must have had on the minds of all who were witnesses of it in the way of predisposing them to believe the extraordinary story, which they were presently to hear, as to what this House or chamber really was, and whence it originally came. We are told that it made its appearance on the shores of Italy towards the very end of the year 1294, and that it was not until some time in 1296 that it was known to be the House of our Blessed Lady from Nazareth. From the first it was recognized as a sacred building, belonging in a special manner to the Holy Virgin, because it contained an image of Her, carved in cedar-wood, and an altar, and because of the many favors which were received there by those who called upon Her name. But more than a year was permitted to elapse before it was made known to them (by means of a vision granted to some pious soul) that it was the very chamber of the Incarnation, which had once been in Nazareth, afterwards translated to Dalmatia, and now brought to Italy. This was a most marvelous history; yet who could say that it was too marvelous to be true, when they had themselves been witnesses of its repeated removal, even within the limits of their own territory, and knew therefore that it was certainly something very sacred, and in a special manner the object of Divine care? Moreover, these repeated translations, if they be true, had the effect of multiplying witnesses of the miracle, or at least evidence of its truth, to an almost indefinite extent. On the whole, therefore, turn the legend which way we will, its texture is such, that what appear at first sight to be its extravagances and extreme improbabilities, on a more minute investigation prove to be real arguments in its favor—on the theory of its falsehood, they are inexplicable; on the theory of its truth, they receive a rational solution.

But let us not dwell any longer on these preliminary considerations... although it would hardly be too much to say that they form the principal part of our subject, for I suppose it is undeniable that the reasons for which the whole story is so laughed to scorn by the whole Protestant world consist entirely in its antecedent improbabilities and apparent strangeness... Whenever a Protestant writer has condescended to enter on any critical examination of the evidence, he has always found it necessary to first apologize to his readers for the insult he may seem to be offering to their understanding by treating the subject with any seriousness at all, as though the idea of a house being carried through the air for any religious purpose were not a self-evident absurdity. And yet it is hard to see why it should be so thought by any who profess to believe in Him Who once said, "If you have faith as a grain of mustard seed, and shall say to this mountain, Remove from hence thither,' it shall remove" (Matt. 17: 19).

We will now proceed to enumerate the principal authors to whom we are indebted for the preservation of the legend of the Holy House, as we at present have it. The earliest authentic account, of which we have a sufficiently distinct notice to make it worth while to mention it in this place, was drawn up by the Bishop of Recanati, though at the time he wrote it he was only the rector of the Sanctuary. Peter George Tolomei had come from Teramo in the Abruzzi to serve in this Church of Santa Maria di Loreto as early as the year 1430, and was promoted to the highest rank in it twenty years afterwards. He compiled a short history for the use of the innumerable pilgrims who came there; and he executed his task so well, that Pope Gregory XIII selected this account a hundred years later to be translated into Arabian, Greek, Illyrian, German, French, Spanish, and Latin, for the same purpose. He seems to have taken great pains in collecting the testimony of the inhabitants. Of course it was impossible that any of that generation should have been himself an eye-witness of the miracle; they could only say what they had been told by others before them. He found two persons in particular (whom he names, and who could be identified therefore and examined by any who had chosen to do so at the time he wrote) whom he examined upon oath. The first swore that he had often heard his grandfather say that his grandfather had seen with his own eyes the House of Loreto coming over the sea like a ship, and that he saw it land in the midst of the forest which ran along the coast. The second swore that he had often heard his grandfather (who lived to the extraordinary age of 120) say that he himself had frequently visited the shrine whilst yet it remained in that wood, and that during this time the angels removed it and carried to the hill belonging to the two brothers...

Six years after the death of Teramano, as this author, from the place of his birth, is generally called—that is, in the year 1479—there came to Loreto a very learned and distinguished ecclesiastic from Mantua, the Provincial of the Carmelite Order, and he too wrote a history, which he dedicated to the Cardinal della Rovere—at that time, Bishop of Recanati—in which he professes to follow the authentic narration of Teramano; only he quotes an additional authority for it—which Teramano too had very probably seen and made use of, though he does not mention it—a very old tablet hung up in the chapel itself. He describes this tablet as almost rotten and consumed with age; so that it may have been written not very long after the first arrival of the House.

Basilica of Loreto.

About forty or fifty years later, the history was rewritten with still greater care and minuteness by Girolamo Angelita, a great antiquary, and enjoying by reason of his official situation—which had also been held by his father and grandfather before him, and seems to have been almost hereditary in his family, the chancellorship of the city of Recanati—many singular advantages for the thorough execution of his task. He tells us that he had sifted, with the most faithful and diligent accuracy, all the ancient annals of the Republic, of whose archives he was the appointed guardian; he had examined also the records which had been received during his lifetime from Fiume and Tersatto, and had been sent to Pope Leo X at Rome; and he dedicated the result of his research to the reigning Pontiff, Clement VII. Copies of this work are still extant, and the only important circumstance which it contains that is wanting in earlier histories is the exact date of the two translations, which are precisely the facts that his situation and the documents that had been sent from Dalmatia might have enabled him to establish with greater certainty.

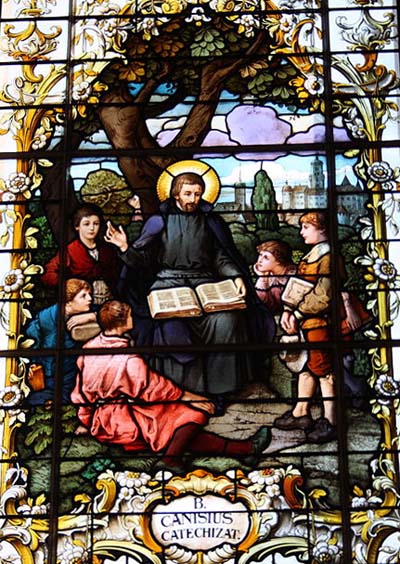

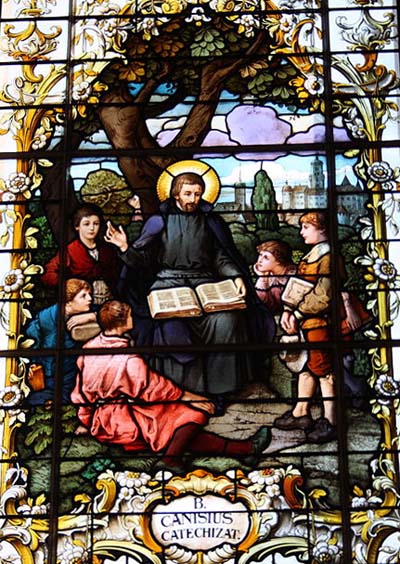

As a matter of evidence, we need hardly examine in detail the writers of later date, because of course they differ in nothing essential from those who have gone before them… As a matter of authority, however, we may enumerate a few of the most distinguished names that appear amongst the list of writers who have defended the authenticity of the miraculous translation, such as Baronius, Rainaldi, St. Peter Canisius, Suarez, Cornelius a Lapide, Noel Alexander, the Bollandists, and Pope Benedict XIV; and since, as Melchior Canus says, “whatever historian the Church has given credit to we need not fear to trust,” it may be worthwhile to add that the whole history of the quadruple translation, together with the causes of each, is incorporated in a Brief of Pope Julius II, bearing the date of November 1, 1502…

We believe the story of the translation of the Holy House, and our fathers before us for many generations have always believed it, on tradition. By tradition is meant what has ever been said, as far as we know, though we do not know how it came to be said, and for that very reason think it true, because else it would not be said... The burden of proof lies with those who wish to destroy the existing belief. We may use the same argument here, then, as has before now been used for the defense of Christianity itself; we may say, in the very words of the author to whom we often allude in this series, "the existence of this testimony is a phenomenon; the truth of the fact solves the phenomenon. If we reject this solution, we ought to have some other to rest in; and none, even by our adversaries, can be admitted which is consistent with the principles that regulate human affairs and human conduct at present, or which make men then to have been a different kind of being from what they are now" (William Paley, 'Evidences for Christianity'). Let the scoffers, then, at the miraculous translation of the House of Loreto come forward and explain to us the origin and history of the evidence that has been adduced; let them tell us how it arose, how it came to be believed; or, if they cannot show by positive accounts how it did, yet let them allege some probable hypothesis how it might have arisen. For myself, I cannot conceive, and I do not remember ever to have heard of, any other answer to this challenge than one of these two: either the building must have been raised in some extraordinary manner is a single night, or if in a longer time, at least in the deepest secrecy, without a single human witness that was not a participant in the deception, and with such consummate skill that when the story was circulated, it looked not like a thing of yesterday, but like a building nearly 1300 years old; or the building must have been old, well known to the neighborhood and always held in veneration, yet its real history is lost, and then this lying fable substituted in its stead.

The first of these hypotheses is so preposterously absurd, that it is difficult to believe that it can ever have been seriously entertained by any reasonable being; and, indeed, when first I met with it in the pages of an English Annual, I imagined that the writer had himself invented it for the purpose of enlivening his pages and making his readers laugh... however, he goes on to allege that, "it very well might so happen, for that the Jesuits (wonderful Jesuits, to have had a hand in this business only two or three centuries before they were in existence!) have been accused before now of building an entire mill in one night near Granada in Spain, in comparison with which the holy cottage is but a trifle;" and (by way of further corroboration), "the walls of the holy cottage are built much as other walls, but the bricks are ill joined and clumsily put together, which plainly evinces that the structure has been raised with greater expedition than skill" (and yet it stands for centuries without any foundation!) The writer of these silly lines probably thought that this fungus-like origin of a famous Catholic sanctuary was a capital joke. We certainly need not be at pains to refute it; a single observation will suffice, viz. that the House does not happen to be built of the bricks that most of the buildings in that neighborhood are, but of a fine-grained limestone, the like of which is not to be found within thirty or forty miles of the place.

The first of these hypotheses is so preposterously absurd, that it is difficult to believe that it can ever have been seriously entertained by any reasonable being; and, indeed, when first I met with it in the pages of an English Annual, I imagined that the writer had himself invented it for the purpose of enlivening his pages and making his readers laugh... however, he goes on to allege that, "it very well might so happen, for that the Jesuits (wonderful Jesuits, to have had a hand in this business only two or three centuries before they were in existence!) have been accused before now of building an entire mill in one night near Granada in Spain, in comparison with which the holy cottage is but a trifle;" and (by way of further corroboration), "the walls of the holy cottage are built much as other walls, but the bricks are ill joined and clumsily put together, which plainly evinces that the structure has been raised with greater expedition than skill" (and yet it stands for centuries without any foundation!) The writer of these silly lines probably thought that this fungus-like origin of a famous Catholic sanctuary was a capital joke. We certainly need not be at pains to refute it; a single observation will suffice, viz. that the House does not happen to be built of the bricks that most of the buildings in that neighborhood are, but of a fine-grained limestone, the like of which is not to be found within thirty or forty miles of the place.

The second hypothesis is this: that the building had been always a sacred one, perhaps even originally built in imitation of the House at Nazareth, in consequence, says Dean Stanley, "of some peasant's dream, or the return of some Croatian chief from the last Crusade, or the story of some Eastern voyager landing on the coast," but that its history was subsequently lost, or at least so far corrupted, as that the building came to be accounted the original of that of which it was in truth only a copy. This hypothesis is, as far as I know, the only one which has ever been adopted by any Catholic writer who has refused to believe the miraculous translation (Calmet—who subsequently retracted this rash conjecture); certainly it is the only one which bears even a semblance of probability; but when it is looked into more carefully, even this semblance disappears. In the first place, how does this supposition account for the several successive translations from Dalmatia to Italy, and from one place to another, more than once, even in Italy itself? "Very probably," it has been said (by Calmet, before his retraction), "all these various translations were only different houses built after the form and fashion of the House at Nazareth, just as we see in many places sepulchers built in imitation of the Holy Sepulcher at Jerusalem." But wherefore could there have been three such within the space of a single mile, and yet so rarely met with elsewhere that not even Calmet himself mentions another instance? Above all, how does this supposition account for the keen sense of loss, the memory of which still lives among the Dalmatians? If they had once had a similar copy and it had been destroyed, yet why should they grudge to the Italians a memorial which, if they pleased, they might so easily renew for themselves—nay which, in point of fact, if this theory were true, they had already renewed—for from an early period in the 14th century they had a church built more or less according to the model of that at Loreto (see image, above right).

But secondly, if we look at the building itself, we shall easily see that it can only be either the original, or designed to be mistaken for such—there is no middle term. Either it is truth or it is a gross imposture; there is no room for a mistake. For first, the House (or chamber, as it might more properly be called) has no foundations. One bent upon practicing a deceit might have done this; or if the translation of the House were miraculous, it might have been so brought; but surely such a thing could never have happened to a shrine built expressly as a memorial, and intended to endure as such to succeeding ages. The fact that the House of Loreto really is without foundations cannot be doubted; it is mentioned by all the earliest historians of the sanctuary; it was formally examined by several persons prior to the raising of the new outer wall in the reign of Pope Clement VII, amongst the rest by Angelita himself, who has left an account of it; and again in the reign of Pope Benedict XIV, when the pavement of the House was taken up and renewed. On this last occasion five bishops were present, three architects, and three master-masons, besides others; and all fully satisfied themselves of the truth of the popular belief on this matter... Moreover, Teramano, Angelita, and the rest tell us that the people of Recanati sought to provide against the consequences which might naturally be apprehended from this essential defect by building a wall around the House, which however could never be brought to attach itself to the original wall of the House itself. This fact too is attested by the same clear evidence as the lack of foundations; for it rests on the testimony of Nerucci, the architect employed by Pope Clement VII, and many others, amongst whom may be specially mentioned John Eck, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ingolstadt, and the well-known opponent of Luther, who at that time examined the building and ascertained that the space between the two walls was such as to admit of a boy walking all round the House between them. Angelita was there when the boy did it; and 60 years afterwards, 1580, when Riera was compiling his history, many persons were still living who had known the boy and had heard him say that he had done it (Torsellino, Storia etc., p. 40). When, under Pope Leo X, the old outer wall, which was of bricks, was removed, and they proceeded to build a stronger one to be encrusted with marble in its stead (see image, below left), we are expressly told that the architect, Rainerius Nerucci, who had beheld the prodigy with his own eyes, left the same interval in order that the memory of so signal a wonder might not perish (Ibid. p. 100).

Another circumstance may be very properly insisted upon in this place, although it has been already mentioned—that the materials of which the building is composed are not to be found within 30 or 40 miles of Loreto, whereas one of the three prelates whom Clement VII sent to Dalmatia and to Palestine for the express purpose of testing the truth of the tradition, as far as might be, by an examination of the various localities, brought away with him two stones of the kind generally used in the buildings of Nazareth, and they were found to exactly correspond with the stones of the Holy House... A short time after the publication of Dean Stanley’s work, Cardinal Wiseman, knowing that Msgr. Bartolini was about to make a pilgrimage to Nazareth, sent him the passages from the book which related to Nazareth and Loreto, and begged him to make a special examination on the points referred to in those passages. As he was a person of consideration in Rome, he was enabled to obtain from the Holy Father permission to remove small portions of stone from the walls of the Holy House, and to have them analyzed. Such a permission was probably never before granted, and the prelate availed himself of it to good purpose. He enclosed in separated papers some specimens of stone which he had brought from Nazareth; also two stones from the Holy House of Loreto which were in the possession of the Cardinal-Vicar of Rome, and some others which he himself removed from the same walls. He then sent all these to the Professor of Chemistry at the Sapienza in Rome, in order that he might analyze them. The Professor was not told where the respective parcels came from. He submitted them to analysis, and reported that all were limestone—the stone of Nazareth, not the volcanic stone of Loreto—and that there was no material difference between them.

Another circumstance may be very properly insisted upon in this place, although it has been already mentioned—that the materials of which the building is composed are not to be found within 30 or 40 miles of Loreto, whereas one of the three prelates whom Clement VII sent to Dalmatia and to Palestine for the express purpose of testing the truth of the tradition, as far as might be, by an examination of the various localities, brought away with him two stones of the kind generally used in the buildings of Nazareth, and they were found to exactly correspond with the stones of the Holy House... A short time after the publication of Dean Stanley’s work, Cardinal Wiseman, knowing that Msgr. Bartolini was about to make a pilgrimage to Nazareth, sent him the passages from the book which related to Nazareth and Loreto, and begged him to make a special examination on the points referred to in those passages. As he was a person of consideration in Rome, he was enabled to obtain from the Holy Father permission to remove small portions of stone from the walls of the Holy House, and to have them analyzed. Such a permission was probably never before granted, and the prelate availed himself of it to good purpose. He enclosed in separated papers some specimens of stone which he had brought from Nazareth; also two stones from the Holy House of Loreto which were in the possession of the Cardinal-Vicar of Rome, and some others which he himself removed from the same walls. He then sent all these to the Professor of Chemistry at the Sapienza in Rome, in order that he might analyze them. The Professor was not told where the respective parcels came from. He submitted them to analysis, and reported that all were limestone—the stone of Nazareth, not the volcanic stone of Loreto—and that there was no material difference between them.

These facts then being so, we might have a right to reject the explanation suggested by Calmet as insufficient and false. This Holy House of Loreto was certainly not an ordinary building, whose real history being lost, an attempt was made in later ages to connect it by a marvelous tale with the scene of the Incarnation. Such an explanation, while getting rid of one miracle, substitutes a dozen others in its stead; it leaves, that is, a dozen facts utterly inexplicable on any ordinary principles of human reasoning. In a word, we may confidently say that all the facts and circumstances which we have enumerated are utterly incompatible with any theory whatever, save only that one which history has recorded and monuments attest, which Popes have sanctioned and the faithful universally received, and to which God Himself has seemed to have set His seal by the innumerable wonders He has wrought there.

History and monuments—in other words, the evidence of authors and facts—have already been sufficiently examined; and the general belief of the faithful is too notorious to stand in need of any proof; in fact it is the very thing with which our adversaries upbraid us. A few words, however, will not be out of place upon the other two points that have been here alluded to: the sanction of the Church through the declaration of the Popes, and the sanction of Almighty God through the instrumentality of miracles or other special outpourings of His grace.

Of all the Popes who have filled the Chair of Peter since the miraculous translation, more than forty have in one way or another given their sanction to the story; some by the grant of indulgences or other privileges, some by the introduction or confirmation of new lessons in the Breviary, some by making pilgrimages there themselves, some even to writing in its defense. Pope Paul II, in 1471, speaks of "the House and Image..." (for within the House there was brought, and has always remained, a very ancient Image of Our Lady, carved in cedar wood. This Image was carried away by the French in 1797, venerated for a time at Notre Dame in Paris, and finally returned to Pope Pius VII, at his urgent request, by Napoleon. When it arrived in Rome, the Pope had it placed first in his chapel at the Quirinal, then exposed for three days in a church in the city, and finally restored to Loreto in December, 1802) "...of the glorious and Blessed Virgin Mary, having been, according to the assertion of persons who may be depended on, translated by a company of the angelic host, and by the wonderful goodness of God set down at Loreto, without the walls of Recanati; and that great and stupendous and innumerable miracles had been wrought there by means of the same most merciful Virgin, as We in our own persons have experienced." He was cured of the plague there, and also our Blessed Lady appeared and announced to him that he would be chosen Pope. Marcellus II had a similar revelation whilst offering Mass in the Holy House. St. Pius V had the Agnus Dei, which he consecrated, stamped with a representation of the Holy House. Benedict XIV enumerates, as the proofs of its authenticity, ancient monuments, unbroken tradition, the declarations of Popes, the common belief of the faithful, and continual miracles...

Although it is quite true that a belief in the identity of the Holy House of Loreto with that in which the Incarnation was accomplished, and in its miraculous translation from Galilee to Italy, is no article of faith, and a man may deny it, if he will, without thereby becoming a heretic, nevertheless it would be well for anyone who is tempted to do so to realize what he is doing. He is assuming that he is more intelligent than the great body of the faithful, who for centuries have venerated this sanctuary and have regarded its history as true. He is assuming that he is more sagacious than the saints, wiser than the Supreme Pontiffs, who have rendered such magnificent testimonies to the truth of its history, and more prudent than the Sacred Congregation of Rites, who have approved the Office of the Translation. Perhaps also it would be well for them to weigh the full significance of the following remarks, written by a very bitter enemy when examining this very subject: "There are individuals in the Roman Church who look upon certain parts of their system as matters in which they are free to please themselves; but, whether in consequence or not, they are certainly none of the holiest... We have discovered that belief and disbelief in the story of the Holy House amongst Roman Catholics go hand in hand respectively with ardent piety and indifferentism" (Christian Remembrancer, No. lxxxiv. N.S.) In other words, a man cannot throw off the spirit of dutifulness and submission to authority from a profound conviction of his own superior knowledge, without suffering spiritual loss.

And yet once more, it may truly be said that the man who rejects the Church's tradition, and resolves within himself that the Holy House is nothing more than any other house, turns a deaf ear to the voice of God Himself, Who has spoken here by means of signs and wonders during more than 700 years. The miracles which He has wrought at this place, says St. Peter Canisius (De M. V. lib. v, c. 25), are so many, that they cannot possibly be numbered; so open and notorious, that none but the most shameless can dare to deny them; of so extraordinary and stupendous a character, that not even the most practiced orator could adequately describe and illustrate them. From far and near men crowd to this sanctuary, men of all ranks and conditions of life, making or paying their vows to the Blessed Virgin, each according to his several necessities: all are animated by the same motive, and aim at one only end, to show forth their devotion or their gratitude to the Mother of God. Some come to give Her thanks because they feel that to Her, after God, they owe their deliverance from grievous diseases, or from dreadful perils by land, by fire, or by water; that from Her, under God, they have received unlooked-for relief in the depths of their distress, when their affairs seemed altogether desperate; by Her they are conscious that they have been tenderly watched and guarded both at home and abroad, amongst friends and amongst enemies, from dangers which they had foreseen, as well as from others of which they knew not. Again, others come because they have near at heart the success of some favorite plan, or because they propose to change their state of life, or because they are weighed down by some heavy affliction, or because they apprehend some evil; and the innumerable offerings that are made, the votive tablets that are suspended, sufficiently attest the fact that their prayers are heard.