Celebrated Sanctuaries of the Madonna

Fifth in a Series

In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author

succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

This chapter was written some ten or more years after the first Apparition of Our Lady at Lourdes. The opening remarks of the author

make it clear that it was the last chapter written for this book; and indeed it is not found in the book's first edition.

Our Lady of Lourdes

Equally celebrated at the present day with the sanctuaries of our Blessed Lady at Loreto, Genazzano (Our Lady of Good Counsel), and La Salette, is the

famous shrine in Her honor at Lourdes in the southwest part of France, whither countless multitudes of the faithful flock from all parts of the Christian world

as in former ages they did to the shrines in Einsiedeln in Switzerland and Walsingham in England. We therefore append a brief sketch of this cherished spot

where Our Lady has so powerfully deigned to intercede with Her Divine Son in the various needs of Her devoted children, in order to properly round out this

volume with a complete list of Our Lady's more celebrated shrines.

Equally celebrated at the present day with the sanctuaries of our Blessed Lady at Loreto, Genazzano (Our Lady of Good Counsel), and La Salette, is the

famous shrine in Her honor at Lourdes in the southwest part of France, whither countless multitudes of the faithful flock from all parts of the Christian world

as in former ages they did to the shrines in Einsiedeln in Switzerland and Walsingham in England. We therefore append a brief sketch of this cherished spot

where Our Lady has so powerfully deigned to intercede with Her Divine Son in the various needs of Her devoted children, in order to properly round out this

volume with a complete list of Our Lady's more celebrated shrines.

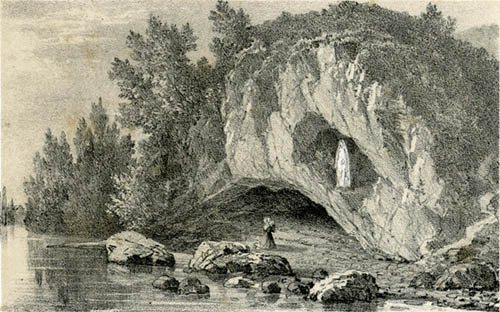

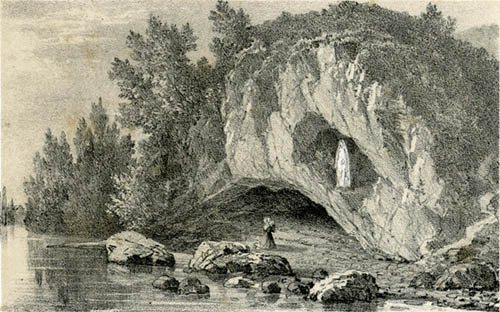

The little town of Lourdes is situated amidst the Pyrenees, near the banks of the river Gave. Its houses scattered irregularly over an uneven

surface are grouped at the base of a huge rock entirely isolated, on whose summit rises like an eagle’s eyrie a castle which in olden times was a formidable

seat of feudal power, and the key of the Pyrenees. Saracen and Christian had in turn kept the stronghold, and in the days of Charlemagne its inmates were

noted for devotion to Our Lady. The people of this out-of-the-way place were and are characterized by the healthy traits of mountaineering races, gifted

with keen, practical, good sense, and still retaining a deep reverence for Faith, which the havoc of the French revolution and the succeeding apathy of

its neighbors was unable to dim. Lourdes was in fact almost singular amidst a people so singularly attached as the French in its strong principle of

organization; patriotic, submissive to the State, they formed altogether a brotherhood of citizens. Societies of beneficence or religion thrived among them,

confraternities of husbandmen, of slaters, of masons and cabinet makers, of tailors and seamstresses, of quarry men, of church wardens, of all classes and

professions or trades; the principle of philanthropy really founded there a shrine. Such was the sterling sense of this good people that to belong to a

society was esteemed an honor—to be discarded, a social stain.

Such was the state of Lourdes (before the apparitions), the railroad did not then pass by it, nor was it indeed in contemplation.

The whole of the town and the fortress was situated on the right bank of the Gave, which breaks against the enormous rock that serves as a pedestal to

the castle. Beyond the river, meadows rolled by its banks—a pasture for the numerous herds of cows. In 1858 there was scarcely a wilder, more savage, or

solitary spot in the environs of the busy little town we have described, than the Rocks of Massabielle, at the foot of which the mill-stream rejoined the Gave.

A few paces above this juncture, on the bank of the stream, the abrupt rock was pierced at its base by three irregular caverns, curiously

placed above each other. The first was on a level with the ground. It had the appearance of a booth at a country fair, or of a badly shaped and very high oven.

An eglantine or wild rose springing from a fissure in the rock, trailed its long branches at the base of the grotto. These caverns were called the Grotto of

Massabielle, from the name of the rocks of which it formed a part. In the dialect of the country, Massabielle means old rocks. At the approach of a storm the

grotto served the poor wayfarer as a shelter, as also the fishermen who were wont to fish with nets in this part of the Gave. As in all caverns of this nature,

the rock was dry in fine weather and slightly humid when it rained. This occasional humidity was only observable on one side, the right on entering—the left

side and the bottom were always as dry as the floor of a drawing-room.

A few paces above this juncture, on the bank of the stream, the abrupt rock was pierced at its base by three irregular caverns, curiously

placed above each other. The first was on a level with the ground. It had the appearance of a booth at a country fair, or of a badly shaped and very high oven.

An eglantine or wild rose springing from a fissure in the rock, trailed its long branches at the base of the grotto. These caverns were called the Grotto of

Massabielle, from the name of the rocks of which it formed a part. In the dialect of the country, Massabielle means old rocks. At the approach of a storm the

grotto served the poor wayfarer as a shelter, as also the fishermen who were wont to fish with nets in this part of the Gave. As in all caverns of this nature,

the rock was dry in fine weather and slightly humid when it rained. This occasional humidity was only observable on one side, the right on entering—the left

side and the bottom were always as dry as the floor of a drawing-room.

On February 11th, 1858, there was inaugurated as usual a season of profane enjoyment which precedes the austerities of Lent. The weather was

cold but very calm. It was eleven o'clock in the morning by the parish church of Lourdes, when two children of a poor but worthy Christian couple were sent

by their parents to gather some small fagots of wood on the common or on the banks of the Gave. The elder of the two has chiefly to do with our story.

A sickly child from birth, she had few opportunities for the enjoyments common to her age. She was about fourteen years old, and to help eke out the

poverty of her parents was early put to service tending sheep, among which she usually passed her days in solitude on the lonely declivities where her

humble flock grazed. Her knowledge was confined to the saying of a few simple prayers of the Church—the Our Father, Hail Mary, and Creed, with the Rosary

(chapelet) of Our Lady, were the sum of her devotional doctrines. Whether because it had been recommended to her, or because it was the simple want

of her innocent soul, everywhere and at all times while engaged in watching her flock, she was in the habit of reciting this prayer of the humble.

It was, as we have said, the 11th of February at eleven in the morning when Bernadette, for so she was named, a younger sister Marie, and a

neighbor's child named Jeanne Abadie set out to gather wherewith to cook their frugal midday meal. Bernadette was named at baptism in honor of the great

St. Bernard, the author of the Memorare. The little ones started out and reached the place where the wood was to be gathered at about noon.

They were near the rocks and, as Bernadette related, she heard the sound as of a blast of wind; she turned around instinctively, believing it to be a storm,

but to her great surprise the poplars which bordered the Gave were perfectly motionless. Not the slightest breeze disturbed their still branches.

Again the roaring began to be audible afresh. Bernadette raised her head, gazed in front of her and uttered, or strove to utter, a cry, which was

stifled in her throat, she shuddered in all her limbs, and confounded, dazzled, bowed down at what she saw before her, she sank to the earth on her knees.

A truly unheard-of spectacle had just met her gaze, but the child must now in her own clear language tell the story, which neither years, nor the artful

interrogatories of countless sharp and curious adversaries, could ever make her vary a single iota.

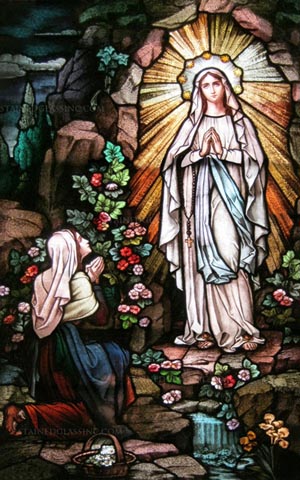

Above the grotto, in a niche formed by the rock, a woman of incomparable splendor stood upright in the midst of superhuman brightness.

She was of middle height, appeared to be quite young, but had the grace of young adulthood. Her garments were of an unknown material and were as white

as the stainless mountain snow; Her robe long and trailing, falling in modest folds around Her, allowed Her feet to appear reposing on the rock, and lightly

pressing the wild rose which trailed there. On each of them expanded the mystic rose of a bright gold color. In front, a girdle, blue as the heavens, was

knotted half way round Her body and fell in two long bands, reaching within a short distance of Her feet. Behind, a white veil, fixed around Her head and

enveloping in its ample folds Her shoulders and the upper part of Her arms, descended as far as the hem of Her robe.

Above the grotto, in a niche formed by the rock, a woman of incomparable splendor stood upright in the midst of superhuman brightness.

She was of middle height, appeared to be quite young, but had the grace of young adulthood. Her garments were of an unknown material and were as white

as the stainless mountain snow; Her robe long and trailing, falling in modest folds around Her, allowed Her feet to appear reposing on the rock, and lightly

pressing the wild rose which trailed there. On each of them expanded the mystic rose of a bright gold color. In front, a girdle, blue as the heavens, was

knotted half way round Her body and fell in two long bands, reaching within a short distance of Her feet. Behind, a white veil, fixed around Her head and

enveloping in its ample folds Her shoulders and the upper part of Her arms, descended as far as the hem of Her robe.

She wore neither rings, nor necklaces, nor diadem, or jewels of any description. A Rosary, with beads as white as milk strung on a chain of

the golden hue of the harvest, hung from Her hands, which were fervently clasped. The beads of the Rosary glided one after the other through Her fingers.

The lips, however, of the Queen of Virgins remained motionless. She was silent.

This marvelous apparition gazed on

Bernadette, who in the first shock of amazement, had, as we have said, sunk down, and without assigning any reason to herself prostrated herself on her knees.

The child in the first moment of astonishment had seized her Rosary, and holding it up between her fingers, wished to make the Sign of the Cross, and carry

it to her bosom. But she trembled to such a degree that she had not the power of raising her arm, and it fell powerless on her bended knee. With a grave

and sweet gesture, which had the air of an all-powerful benediction for earth and Heaven, the Virgin made the Sign of the Cross, as with the view of reassuring

the child. The hand of Bernadette raising itself by degrees, as if invisibly lifted by Her who is called the Help of Christians, made the sacred sign at the

same moment. The child was no longer afraid. Dazzled, fascinated, having nevertheless occasional doubts about herself, and rubbing her eyes, her gaze constantly

attracted by this celestial apparition, she humbly recited her Rosary. At the moment of her concluding it, the Virgin, so radiant with light, all of a sudden

disappeared.

Bernadette being completely restored to herself rejoined her companions. Marie and Jeanne had observed her falling on her knees, and engaging

in prayer, but this, thank God, was not an event of rare occurrence among the pious children of the mountains, and being occupied with their task they had

not paid any attention to the circumstance. Bernadette was surprised at the complete calmness of her sister and Jeanne, who having just then finished their work,

had entered the grotto to play. Have you seen nothing?

she asked. They then remarked that she appeared agitated and excited. No,

they replied.

Have you seen anything?

If you have seen nothing, I have nothing to tell you,

replied Bernadette.

The little bundles were soon made up, and the three maidens started on their return to Lourdes. Bernadette, however, was not able to conceal

her troubled state of mind. On their way home Marie and Jeanne urged her to tell them what she had seen. The little shepherd girl gave way to their entreaties,

having first exacted of them a pledge of secrecy. I have seen,

she said, something clothed in white,

and she described to them in the best

language she could her marvelous vision. Now you know what I have seen,

she said at the termination of her narration, but I beg of you not to say

anything about it.

Marie and Jeanne had no doubts on the subject, but they were terrified. It is perhaps something to do us harm,

they observed,

do not let us go there again, Bernadette.

The confidantes of the little shepherd girl had scarcely reached home, when they found themselves unable to keep the secret any longer.

Marie related all the circumstances to her mother. It is all nonsense,

said the mother. What is this your sister is telling me?

she continued

addressing Bernadette. The girl recounted her vision, and her mother shrugged her shoulders. You are deceived. It was nothing at all. You fancied you

saw something and you have seen nothing. It is all mere folly and nonsense.

Still Bernadette persisted. At all events,

rejoined the mother,

do not go there any more, I forbid you to do so.

Now the prohibition weighed very heavily, for Bernadette had the greatest desire to see the Apparition again. However, she submitted and made

no reply. Two days passed by, and the extraordinary event formed the constant subject of conversation for the three children. An ardent desire of again

seeing the incomparable Lady, for the name of Lady

was the one she had given Her, filled Bernadette's soul.

So on the following Sunday,

Bernadette begged her sister Marie, Jeanne, and some other girls to urge her mother to remove her prohibition and permit them to again visit the Rocks of

Massabielle. The children demanded this in a body after the midday repast, and the mother, after raising many objections, which were all swept away by the

enthusiastic believers, ended by giving assent. The little group first proceeded to the church and devoted a few moments to prayer. One of Bernadette's

companions had taken the precaution to bring with her a bottle of holy water, under the apprehension that the vision might prove to be a snare of the evil spirit.

On their arrival at the grotto, Bernadette said,

So on the following Sunday,

Bernadette begged her sister Marie, Jeanne, and some other girls to urge her mother to remove her prohibition and permit them to again visit the Rocks of

Massabielle. The children demanded this in a body after the midday repast, and the mother, after raising many objections, which were all swept away by the

enthusiastic believers, ended by giving assent. The little group first proceeded to the church and devoted a few moments to prayer. One of Bernadette's

companions had taken the precaution to bring with her a bottle of holy water, under the apprehension that the vision might prove to be a snare of the evil spirit.

On their arrival at the grotto, Bernadette said, Let us pray.

The children accordingly knelt down and commenced to recite the Rosary.

All at once the countenance of Bernadette appeared to be transfigured, an extraordinary emotion was depicted on her countenance, the marvelous

Apparition had just become manifest to her eyes, Her feet resting on the rock, and clothed as on the former occasion. Look,

she said, She is there.

But the other girls looked in vain; they perceived naught but the solitary rock, and the branches of the wild rose, which descended to the base of the

mysterious niche, in which Bernadette was contemplating the unknown Being. Bernadette, after a brief interval, took fresh heart, and bade the Lady approach,

if She came on the part of God. This She did, smiling on the child with affection as if to encourage her, but after a short while She disappeared.

When this second apparition of the vision had been told to her parents, it was not long before the story was circulated among the townspeople

and the peasants. Some believed it, others disputed it, thinking it merely an illusion of the little girl. Others suggested to her to interrogate it should

the vision appear again, and discover what and who it was. It is doubtless some soul from Purgatory,

thought they, which entreats for Masses.

And they went in search of Bernadette. Ask this Lady who She is and what She wishes,

they said to Bernadette, let Her explain this to you, or,

as you may not be able to understand Her will, let Her commit it to writing, which would be better still.

Bernadette obtained fresh permission from her parents to visit the grotto, though they were sorely puzzled at the child's persistence.

She went there the following morning at about six o’clock, after having first assisted at early Mass. Again she said her Rosary, when all of a sudden

the Apparition beamed on her. Her companions saw nothing except the intensely gratified expression of their favored little companion. The Apparition

spoke to her; it bade her approach. She drew near with a paper in her hand ready to take down the behests of the heavenly Visitor. Bernadette was not afraid,

but filled with ecstatic bliss at the condescension of the wonderful Lady. O Lady,

said the child, if You have anything to communicate to me,

would You have the kindness to inform me in writing who You are and what You want.

The divine Virgin smiled at the artless simplicity of the little girl's request. There is no occasion,

She replied, to commit to

writing what I have to tell you. Only do me the favor to come here every day for fifteen days.

I promise You this,

said Bernadette.

And I,

rejoined the Lady, promise to render you happy, not in this but in the other world.

On being asked by Bernadette, if it would

be displeasing to Her if the other children were to accompany Her every day for the fifteen days, they may return with you,

replied the Virgin,

and others beside. I desire to see many persons here.

Saying these words She disappeared.

On her return to Lourdes, Bernadette had to inform her parents of the promise she had made to the mysterious Lady, and of the fifteen days

in which she was to repair to the grotto.

The wonder grew. Everybody spoke about it. The news spread in the mountains and valleys in all directions and in the nearest towns.

On the 19th of February, 1858, a hundred persons were assembled at the grotto. Some irresistible power seemed to have aroused everyone at the word of an

ignorant shepherd girl. In the workshops and yards, in the interior of families, at the parties of the higher classes, among clergy and laymen, at the

houses of the rich and poor, at the club, in the cafes and hotels, on the squares, in the streets, evening and morning, in public and in private, nothing

else was talked about.

Popular instinct recognized the Apparition. It is beyond doubt the Blessed Virgin,

they said. The savants declared against its being

supernatural. The child is under a hallucination, a strong fancy—it is a nervous malady, there is nothing at all in it, was their voice. The newspapers of

the day sapiently explained it on natural grounds; they called Bernadette a visionary.

Such were the observations of all. They had seen enough to know at least that Bernadette was not acting a part. All these facts had made a

strong impression on the clergy, but with wonderful tact and good sense, they had from the very first occasion maintained the most prudent and reserved attitude.

The parish priest, the Abbé Peyramale—a worthy guide of the people, gifted with much native piety, but withal with a strong fund of shrewd common sense,

especially kept aloof from the grotto. Let us remain quiet,

he said, possibly it is a work of God; let us not interfere—His ways are mysterious,

we often do not understand them. Let us await the wise decision of the Bishop—if these facts proceed from the Almighty, He will mark the moment for us to act;

now let Providence follow His way.

The clergy among themselves were

busily engaged in determining the nature of the apparition. The Voltairians of the place admitted only one solution of the fact as possible; the clergy

perceived several. The child was entirely unknown to them. The entire body of the clergy, without a single exception, kept aloof from the child, and did

not make their appearance even at the grotto. They waited.

The clergy among themselves were

busily engaged in determining the nature of the apparition. The Voltairians of the place admitted only one solution of the fact as possible; the clergy

perceived several. The child was entirely unknown to them. The entire body of the clergy, without a single exception, kept aloof from the child, and did

not make their appearance even at the grotto. They waited.

The magistrates were very wise—in their own minds. They must stop this business, it might raise a revolution against the government,

might spread contagion, etc. Bernadette was cited before the commissary of police in presence of the town physician, and was put to a long and subtle

examination. The child never varied a jot in her replies; she was threatened with imprisonment, her father even was menaced if he did not keep Bernadette

at home.

Father,

the poor child said, when I go there, it is not altogether of myself. At a certain moment there is something which calls

me and attracts me.

But the subtleties and menaces proved fruitless. At the next visit to the grotto, the Lady addressed her in sweet tones. Bernadette,

said the Divine Mother, I have a secret to tell you, for yourself alone, and you are never to repeat it to anyone in this world.

Then after telling it,

She said to the child, Go to the priests and tell them to raise a chapel to Me here.

And She disappeared.

What did the Vision say to you?

was the question which escaped from the lips of all. Bernadette astonished on this, as on the preceding

visits, that everyone had not heard the dialogue and seen the Lady, replied: She told me two things—the one for myself alone, and the other for the priests,

and I am going immediately to tell them.

And in haste she took the road to deliver her message. On her arrival in the town, Bernadette—humble and simple

in appearance, her poor garments patched in many places, her head and shoulders covered with her little white capulet of the coarsest material, entered the

abode of the good Abbé Peyramale, to deliver to the representative of the Church her mission from Heaven.

Father,

said the little ambassadress, I come on the part of the Lady who appears to me in the grotto of Massabielle. She has not told

me who She is. I know not whether She is the Blessed Virgin, but I see Her as I now see you, and She speaks to me as you are doing now, and I came to tell you

from Her, that She wishes a chapel to be erected to Her at the Rocks of Massabielle, where She appears to me.

The venerable and prudent ecclesiastic

determined to put the vision to another test. Go,

he said to Bernadette, the Apparition you tell me, has under Her feet a wild-rose—an eglantine—which

grows out of the rock. We are now in the month of February; go, tell Her from me, if She wishes the chapel, She may cause the wild-rose to bloom.

Saying which he dismissed the child.

But the Abbé was doomed to disappointment. Bernadette on her return from the visit to the grotto reported that the Lady smiled when she told

Her that her parish priest requested the wild-rose to bloom; and that She bade her to pray for sinners, and then, imparting to her a second secret,

disappeared.

Again did Bernadette visit her beloved grotto—the child could not keep from it long—she was mysteriously drawn to it in the hopes of again seeing

the beautiful Lady. Go,

said this Consoler of Christians, when Bernadette had come to the grotto on leaving the parish priest, go; drink from and wash

yourself in the Fountain, and eat of the herb which is growing at its side.

Bernadette, at this word Fountain,

gazed around her. There never had

been a spring in the grotto; it had always been perfectly dry. So she went towards the river Gave, which was running not many paces off, when the Apparition

hailed her again, do not go there,

She said. I have not spoken of the Gave; go to the Fountain, it is here,

and with a gesture She pointed out

to the child the right side of the grotto—a dry piece of ground—where Bernadette, after some moments' surprise, spied a tuft of an herb belonging to the

saxifrage family, of which she ate a bit, and in obedience to the Vision, stooping down and scratching away the ground with her tiny hands, began to scoop

out the earth—and lo! in a few moments water appeared, a few drops at first, then a more copious flow, and then enough to fill the cavity and run over the

grotto floor towards the Gave. Bernadette drank of this and the Vision disappeared.

This Fountain was certainly something new. It at least was visible. None could explain it any more than the mysterious Vision. How could

water spring forth from the dry rock, where water had never been seen before? The Fountain grew larger, the stream broadened and deepened. Instead of a

few drops, it poured forth a current the size of a child's arm. This was on the 25th of February, the third Thursday of the month—a great market-day at Tarbes,

a town near Lourdes, whence the people excited out of their natural course at the singular and wonderful reports of what was taking place near the Rocks of

Massabielle, came to Lourdes in multitudes to see for themselves the child who was so singularly favored by Heaven, and the Fountain that had sprung forth

from a dry rock.

The enthusiasm grew. There

was in the town a poor workman known by everyone. His name was Louis Bourriette. He had from twenty years back completely lost the use of his right eye.

But after a single application of the water from the Fountain, he recovered his sight fully. Everyone knew of the misfortune that once was his, everyone in

Lourdes now was witness to his restoration.

The enthusiasm grew. There

was in the town a poor workman known by everyone. His name was Louis Bourriette. He had from twenty years back completely lost the use of his right eye.

But after a single application of the water from the Fountain, he recovered his sight fully. Everyone knew of the misfortune that once was his, everyone in

Lourdes now was witness to his restoration.

Yet the clergy still kept aloof. Let us wait patiently,

they said. In human affairs it is enough to be prudent once. In things

pertaining to God, our prudence should be seventy-fold.

Not a single priest appeared among the throngs of people that almost unceasingly went in

procession to the wonderful grotto. But among the people burned the greatest enthusiasm, the deepest curiosity. They carried their sick to the waters

for cure; they brought them back healed. Soldiers from the neighboring posts got leave to visit Lourdes. Hither, too, flocked their officers, with groups

of public functionaries, lawyers, physicians, scholars, all with varying motives, some to doubt, and some to revere the mysterious ways of Providence,

Who had deigned to speak so marvelously through a poor, ignorant shepherd girl.

On the 2nd of March, Bernadette returned again to the residence of the parish priest of Lourdes, and spoke to him a second time in the name

of the Apparition. She wishes a chapel to be erected, and processions to the grotto to be organized,

said the child. The priest had no further proofs

to demand, and he demanded none. His conviction was settled, and thenceforth no doubt could touch his heart. He had acted prudently, neither he nor his brother

ecclesiastics could in any manner be said to have taken so far any step whatever in the matter. They had prayed—that was their business; they had withheld from

every demonstration looking like an approval of what Bernadette had recounted. But the publicity now of the marvel, the witnessing of thousands, the cures

effected, justified a change in their hitherto prudent inactivity. I believe you,

said the Abbé to Bernadette, but what you demand of me in the

name of the Apparition does not depend on myself—it depends on the Bishop; I will go to him—he alone can act in this affair.

This was enough.

The Abbé Peyramale explained to the Bishop the surprising events of which the grotto of Massabielle and the town of Lourdes had been the scene for

nearly the last three weeks. He recounted the visions of Bernadette, the words uttered by the Apparition, the gushing forth of the spring, the sudden

cures effected, and the excitement which pervaded the whole community.

The Bishop at first would not pronounce any opinion. It is not yet time for the episcopal authority to busy itself with this affair.

We must proceed slowly, give time for reflection, and request to be enlightened, in order to have a careful investigation of facts.

Such was the

language used by the Bishop.

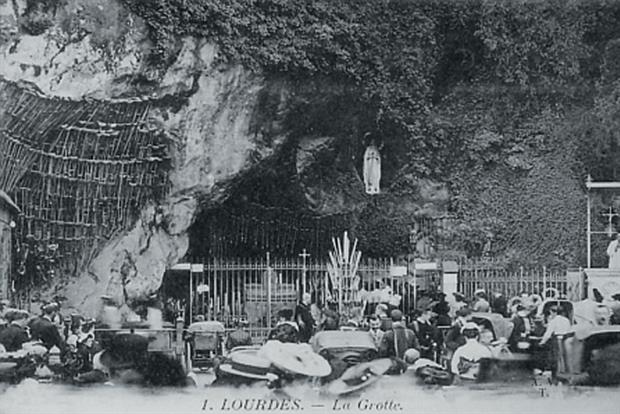

Thursday, the 4th of March, came around. When daybreak began to silver the horizon, the approaches to the grotto were more densely crowded

than on any of the preceding days. A painter such as Raphael or Michelangelo might have derived from the living spectacle a subject for an admirable picture.

Here were all classes of people—old mountaineers with their families, ancient matrons, maidens, youths, peasants from the districts of Bearn and the Basque

provinces, men of all professions, magistrates, shepherds, notaries, lawyers, doctors, clerks, ladies and shopkeepers. There could not have been fewer than

twenty thousand persons. Around about this crowd came and went the police, but their services were not required. All seemed to be filled with the love of order;

nearly all were believers—only a few were skeptics. When Bernadette prostrated herself, everyone by a unanimous movement knelt down. What a scene!

Here in the cool, refreshing air of a lovely spring morning, the beams of the rising sun gilding the tips of the rocks of Massabielle, the crowds firm

in their Faith, yet harrowed with suspense, surrounding silently and reverently, yet curiously, the chief figure in their midst—a little peasant girl

of Lourdes, anxious to learn through her what Heaven designed to tell them. The Apparition, as on the preceding days, had commanded the child to drink

at and wash herself in the Fountain, and to eat of the plant to which we have referred; She had afterwards renewed Her order to go and tell the priests

that She desired a chapel built on the spot and processions to repair to it.

The child had besought

the Apparition to inform her of Her name, but the radiant Lady had not returned any answer to the question.

The moment for doing so had not yet arrived. So the child returned to her home, and although on the intervening days she made, as usual, several

visits to the grotto, she heard no voice, saw no apparition until the 25th of March, the Feast of Our Lady's Annunciation. On this day the crowd

surrounded the child all anxious, all confident that something singular would take place. Bernadette, too, was filled with a joyful presentiment

of some yet unknown bliss. As soon as she had fallen on her knees at the hallowed spot, the Apparition made Herself manifest. Bernadette,

plunged in ecstasy, forgot earth in the presence of the Spotless Beauty.

The child had besought

the Apparition to inform her of Her name, but the radiant Lady had not returned any answer to the question.

The moment for doing so had not yet arrived. So the child returned to her home, and although on the intervening days she made, as usual, several

visits to the grotto, she heard no voice, saw no apparition until the 25th of March, the Feast of Our Lady's Annunciation. On this day the crowd

surrounded the child all anxious, all confident that something singular would take place. Bernadette, too, was filled with a joyful presentiment

of some yet unknown bliss. As soon as she had fallen on her knees at the hallowed spot, the Apparition made Herself manifest. Bernadette,

plunged in ecstasy, forgot earth in the presence of the Spotless Beauty. O Lady,

she said to Her, would You have the goodness to inform

me who You are and what is Your name?

The queenly Apparition at first made no reply, but moved at the insistence of Bernadette, who again and

again with childish pleading urged her request, the Queen of Heaven at last yielded to the innocent worshiper, and raising Her hands towards the heavens,

pronounced these words: I am the Immaculate Conception.

Thus saying, She disappeared, and the child, like the multitude, found herself opposite

a solitary rock, at her side the miraculous Fountain soothing the ear with the peaceful flow of its waters, and naught around to disturb the blissful

recollections in her heart.

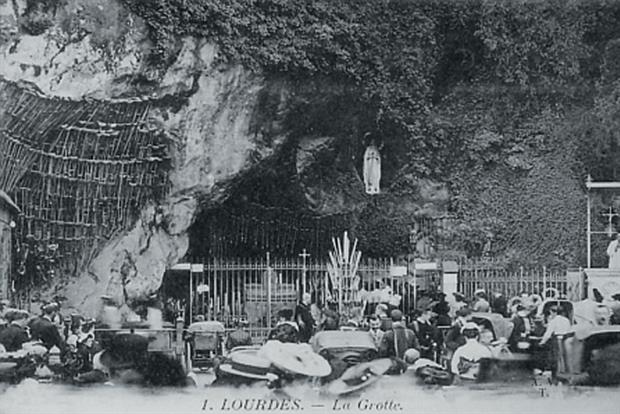

The unbelievers of the day attempted in vain to stem the tide of religion, but they could find no law in the code against miracles.

The Bishop was at first in a quandary how to act—whether to formally recognize the Apparition as a Divine manifestation, or to formally interdict

all credence in Bernadette as a mere visionary.

The roads to Massabielle continued to be thronged, miracles were wrought by bathing in the

water of the fountain, persons living at a distance had bottles of it brought to them, even some dead were said to be raised to life. The pious

townspeople and artisans made a road to the shrine, crimes ceased in the neighborhood, an air of religion diffused itself around the valleys of Lourdes.

What could the Bishop do, but yield to the manifest will of Providence? So he authorized the Abbé Peyramale to begin a chapel on the site of the healing

pool, to Her who wished the place dedicated to Her name.

Eighteen times had the Blessed Virgin appeared to Bernadette since her first vision on February 11, 1858, and on January 18, 1862,

an appeal was made by the prudent and venerable Bishop of Tarbes to the faithful everywhere throughout Christian lands to concur in the founding

of a temple at Lourdes. Now one may see a superb church proudly seated on the Rocks of Massabielle. As to Bernadette, she became a Sister of Charity,

among the good nuns at Nevers, and took the name in religion of Sister Marie-Bernarde. (St. Marie-Bernarde Soubirous was canonized by Pope Pius XI

on December 8, 1933.)

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

Equally celebrated at the present day with the sanctuaries of our Blessed Lady at Loreto, Genazzano (Our Lady of Good Counsel), and La Salette, is the

famous shrine in Her honor at Lourdes in the southwest part of France, whither countless multitudes of the faithful flock from all parts of the Christian world

as in former ages they did to the shrines in Einsiedeln in Switzerland and Walsingham in England. We therefore append a brief sketch of this cherished spot

where Our Lady has so powerfully deigned to intercede with Her Divine Son in the various needs of Her devoted children, in order to properly round out this

volume with a complete list of Our Lady's more celebrated shrines.

Equally celebrated at the present day with the sanctuaries of our Blessed Lady at Loreto, Genazzano (Our Lady of Good Counsel), and La Salette, is the

famous shrine in Her honor at Lourdes in the southwest part of France, whither countless multitudes of the faithful flock from all parts of the Christian world

as in former ages they did to the shrines in Einsiedeln in Switzerland and Walsingham in England. We therefore append a brief sketch of this cherished spot

where Our Lady has so powerfully deigned to intercede with Her Divine Son in the various needs of Her devoted children, in order to properly round out this

volume with a complete list of Our Lady's more celebrated shrines. A few paces above this juncture, on the bank of the stream, the abrupt rock was pierced at its base by three irregular caverns, curiously

placed above each other. The first was on a level with the ground. It had the appearance of a booth at a country fair, or of a badly shaped and very high oven.

An eglantine or wild rose springing from a fissure in the rock, trailed its long branches at the base of the grotto. These caverns were called the Grotto of

Massabielle, from the name of the rocks of which it formed a part. In the dialect of the country, Massabielle means old rocks. At the approach of a storm the

grotto served the poor wayfarer as a shelter, as also the fishermen who were wont to fish with nets in this part of the Gave. As in all caverns of this nature,

the rock was dry in fine weather and slightly humid when it rained. This occasional humidity was only observable on one side, the right on entering—the left

side and the bottom were always as dry as the floor of a drawing-room.

A few paces above this juncture, on the bank of the stream, the abrupt rock was pierced at its base by three irregular caverns, curiously

placed above each other. The first was on a level with the ground. It had the appearance of a booth at a country fair, or of a badly shaped and very high oven.

An eglantine or wild rose springing from a fissure in the rock, trailed its long branches at the base of the grotto. These caverns were called the Grotto of

Massabielle, from the name of the rocks of which it formed a part. In the dialect of the country, Massabielle means old rocks. At the approach of a storm the

grotto served the poor wayfarer as a shelter, as also the fishermen who were wont to fish with nets in this part of the Gave. As in all caverns of this nature,

the rock was dry in fine weather and slightly humid when it rained. This occasional humidity was only observable on one side, the right on entering—the left

side and the bottom were always as dry as the floor of a drawing-room. Above the grotto, in a niche formed by the rock, a woman of incomparable splendor stood upright in the midst of superhuman brightness.

She was of middle height, appeared to be quite young, but had the grace of young adulthood. Her garments were of an unknown material and were as white

as the stainless mountain snow; Her robe long and trailing, falling in modest folds around Her, allowed Her feet to appear reposing on the rock, and lightly

pressing the wild rose which trailed there. On each of them expanded the mystic rose of a bright gold color. In front, a girdle, blue as the heavens, was

knotted half way round Her body and fell in two long bands, reaching within a short distance of Her feet. Behind, a white veil, fixed around Her head and

enveloping in its ample folds Her shoulders and the upper part of Her arms, descended as far as the hem of Her robe.

Above the grotto, in a niche formed by the rock, a woman of incomparable splendor stood upright in the midst of superhuman brightness.

She was of middle height, appeared to be quite young, but had the grace of young adulthood. Her garments were of an unknown material and were as white

as the stainless mountain snow; Her robe long and trailing, falling in modest folds around Her, allowed Her feet to appear reposing on the rock, and lightly

pressing the wild rose which trailed there. On each of them expanded the mystic rose of a bright gold color. In front, a girdle, blue as the heavens, was

knotted half way round Her body and fell in two long bands, reaching within a short distance of Her feet. Behind, a white veil, fixed around Her head and

enveloping in its ample folds Her shoulders and the upper part of Her arms, descended as far as the hem of Her robe. So on the following Sunday,

Bernadette begged her sister Marie, Jeanne, and some other girls to urge her mother to remove her prohibition and permit them to again visit the Rocks of

Massabielle. The children demanded this in a body after the midday repast, and the mother, after raising many objections, which were all swept away by the

enthusiastic believers, ended by giving assent. The little group first proceeded to the church and devoted a few moments to prayer. One of Bernadette's

companions had taken the precaution to bring with her a bottle of holy water, under the apprehension that the vision might prove to be a snare of the evil spirit.

On their arrival at the grotto, Bernadette said,

So on the following Sunday,

Bernadette begged her sister Marie, Jeanne, and some other girls to urge her mother to remove her prohibition and permit them to again visit the Rocks of

Massabielle. The children demanded this in a body after the midday repast, and the mother, after raising many objections, which were all swept away by the

enthusiastic believers, ended by giving assent. The little group first proceeded to the church and devoted a few moments to prayer. One of Bernadette's

companions had taken the precaution to bring with her a bottle of holy water, under the apprehension that the vision might prove to be a snare of the evil spirit.

On their arrival at the grotto, Bernadette said,  The clergy among themselves were

busily engaged in determining the nature of the apparition. The Voltairians of the place admitted only one solution of the fact as possible; the clergy

perceived several. The child was entirely unknown to them. The entire body of the clergy, without a single exception, kept aloof from the child, and did

not make their appearance even at the grotto. They waited.

The clergy among themselves were

busily engaged in determining the nature of the apparition. The Voltairians of the place admitted only one solution of the fact as possible; the clergy

perceived several. The child was entirely unknown to them. The entire body of the clergy, without a single exception, kept aloof from the child, and did

not make their appearance even at the grotto. They waited. The enthusiasm grew. There

was in the town a poor workman known by everyone. His name was Louis Bourriette. He had from twenty years back completely lost the use of his right eye.

But after a single application of the water from the Fountain, he recovered his sight fully. Everyone knew of the misfortune that once was his, everyone in

Lourdes now was witness to his restoration.

The enthusiasm grew. There

was in the town a poor workman known by everyone. His name was Louis Bourriette. He had from twenty years back completely lost the use of his right eye.

But after a single application of the water from the Fountain, he recovered his sight fully. Everyone knew of the misfortune that once was his, everyone in

Lourdes now was witness to his restoration. The child had besought

the Apparition to inform her of Her name, but the radiant Lady had not returned any answer to the question.

The moment for doing so had not yet arrived. So the child returned to her home, and although on the intervening days she made, as usual, several

visits to the grotto, she heard no voice, saw no apparition until the 25th of March, the Feast of Our Lady's Annunciation. On this day the crowd

surrounded the child all anxious, all confident that something singular would take place. Bernadette, too, was filled with a joyful presentiment

of some yet unknown bliss. As soon as she had fallen on her knees at the hallowed spot, the Apparition made Herself manifest. Bernadette,

plunged in ecstasy, forgot earth in the presence of the Spotless Beauty.

The child had besought

the Apparition to inform her of Her name, but the radiant Lady had not returned any answer to the question.

The moment for doing so had not yet arrived. So the child returned to her home, and although on the intervening days she made, as usual, several

visits to the grotto, she heard no voice, saw no apparition until the 25th of March, the Feast of Our Lady's Annunciation. On this day the crowd

surrounded the child all anxious, all confident that something singular would take place. Bernadette, too, was filled with a joyful presentiment

of some yet unknown bliss. As soon as she had fallen on her knees at the hallowed spot, the Apparition made Herself manifest. Bernadette,

plunged in ecstasy, forgot earth in the presence of the Spotless Beauty.