Celebrated Sanctuaries of the Madonna

Sixth in a Series

In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author

succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

While some the material covered in this and other chapters of Fr. Northcote’s book have already been discussed in past articles

(see Salve Maria Regina Issue No. 148), Fr. Northcote adds many interesting facts, as well as his usual excellent apologetics.

Our Lady of Good Counsel, Genazzano

Genazzano is a town of some importance in the diocese of Palestrina, very prettily situated on the left of the high road to Naples,

at a distance of about thirty miles to the south-east of Rome. From time immemorial, the Feast of St. Mark the Evangelist was celebrated

there as a very special holiday; in fact, it was the day of the great fair or market of the year. Moreover, there was a very old church

in the city, dedicated to the Madonna of Good Counsel—built, as it would appear, upon a part of the territory that Pope Sixtus III

had conveyed as an endowment to St. Mary Major's in Rome, on the occasion which has been already mentioned (in

Issue No. 189) of his rebuilding that Basilica.

Genazzano is a town of some importance in the diocese of Palestrina, very prettily situated on the left of the high road to Naples,

at a distance of about thirty miles to the south-east of Rome. From time immemorial, the Feast of St. Mark the Evangelist was celebrated

there as a very special holiday; in fact, it was the day of the great fair or market of the year. Moreover, there was a very old church

in the city, dedicated to the Madonna of Good Counsel—built, as it would appear, upon a part of the territory that Pope Sixtus III

had conveyed as an endowment to St. Mary Major's in Rome, on the occasion which has been already mentioned (in

Issue No. 189) of his rebuilding that Basilica.

This church was in the hands of the Augustinians, to whom it had been given, in the year 1356, by some member of the Colonna family,

the feudal lords of the place. It was neither large nor comely; and about the middle of the 15th century, a devout old woman named

Petruccia da Janeo, a native of Genazzano and a member of the Third Order of St. Augustine, declared her determination to rebuild it

on a scale of greater magnificence. Her means were wholly unequal to the task; nevertheless, such as they were, she devoted them entirely

to the work. She went and sold all that she had, and the undertaking was begun. Her friends and neighbors laughed her to scorn, as one

who had begun to build without having first sat down and reckoned the charges that were necessary, whether she had wherewithal to finish it

(Luke 14: 28). Her relatives—not without some suspicion of a selfish regard to their own interests as the motive of their

interference—rebuked her sharply for her improvidence, in thus voluntarily depriving herself of those means of support with which

God had blessed her in the time of her greatest necessity; she was old and infirm, they said, and who would undertake the burden

of her support, since her impoverishment had been the result of a foolish indulgence of her own fancy? Her answer to these objections

was always the same: The work will be finished and that right soon, because it is not my work, but God's; the Madonna and St. Augustine

will do it before I die;

and she continually repeated, with an air of confidence, what may have seemed the ravings of madness to those

who heard her, Oh, what a Gran Signora (what a Noble Lady) will soon come and take possession of this place!

Meanwhile the work proceeded, and the walls had already risen high above the ground, close to the old church which they were

intended to enclose. But by and by the builders ceased; and now there arose a far greater obstacle than the mere insufficiency of means.

Petruccia had in fact declared that she had begun her undertaking, and was encouraged to persevere with it mainly in reliance upon some

secret inspiration, vision, or revelation (it does not clearly appear which), that she believed herself to have received from God;

and the Church, in order to guard against abuses which had sometimes arisen from giving heed to pretended supernatural messages of this kind,

had now issued a law forbidding such things to be attended to, unless they were corroborated by some other external and independent testimony;

the mere assertion of a dream, a vision, or a revelation, was on no account to be obeyed. Petruccia's work, therefore, was not only suspended

for want of means, it was also canonically prohibited. Her own substance had been exhausted, and an appeal to the assistance of others

the ecclesiastical authorities could not permit.

Matters were in this state in

the spring of 1467. On Saturday, April 25, in that year, the usual fair had been held; crowds of people had passed and repassed the old church,

and the imperfect walls of the new; and we cannot doubt but that some at least amongst those who saw them had begun to mock, saying,

Matters were in this state in

the spring of 1467. On Saturday, April 25, in that year, the usual fair had been held; crowds of people had passed and repassed the old church,

and the imperfect walls of the new; and we cannot doubt but that some at least amongst those who saw them had begun to mock, saying,

This woman began to build, and was not able to finish.

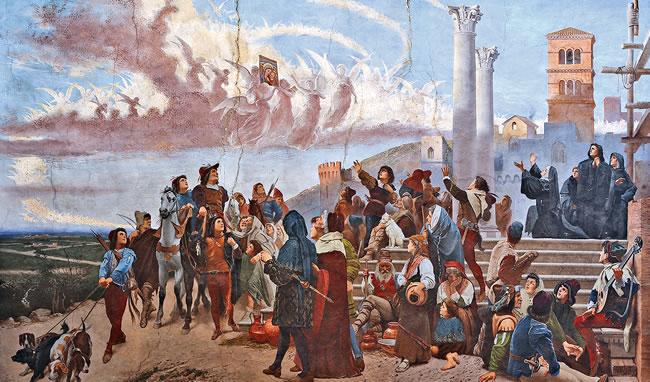

Evening was fast approaching, the gayest, brightest hour of the fair,

when, business being ended, the pleasure of the day began. All were devoting themselves to amusement, each in his own way,

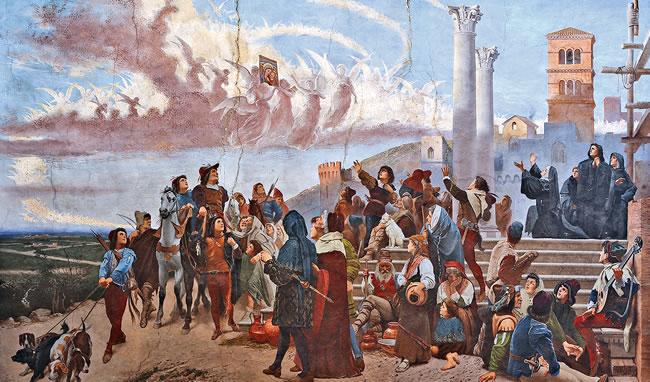

when presently some who stood in the piazza saw something like a thin cloud floating in the air, and then settling on one of the walls

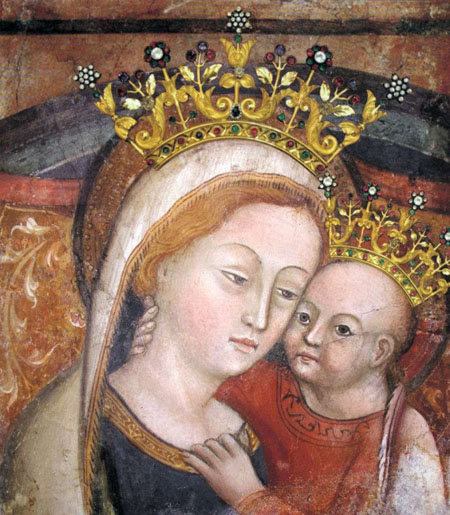

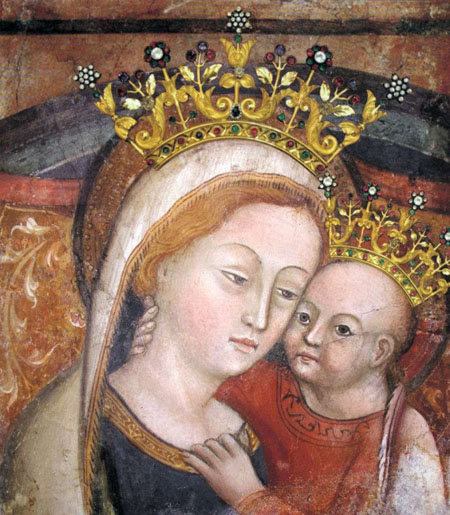

of the unfinished building. Here the cloud seemed to divide and disappear, and there remained upon the wall a picture of the Madonna and Child,

which had not been there before—a picture which was new to all the bystanders, and which they could not in any way account for.

At the same moment the bells of the church, and of all the other churches in the town, began to sound, yet no human hand was seen to touch them.

People ran from their houses to ask the cause of this general alarm; and indistinct rumors spread rapidly amongst them that

something wonderful had happened in the Piazza della Madonna. Those who were nearest to the spot arrived just in time to see the aged

Petruccia come out from the church, to inquire like the rest what had happened. When she had seen the picture, she threw herself on her knees

and saluted it with outstretched arms; then she arose, and turning round to the people, told them with a voice half choked with tears of joy

and gratitude, that this was the Gran Signora whom she had so long expected—that She was now come to take possession of the church

that ought to have been prepared for Her, and that the bells were sounding in this miraculous way only to do Her honor.

At this intelligence the people fell upon their knees, and began to pour forth their prayers before this marvelous painting,

which they knew not how otherwise to designate than as the Madonna del Paradiso.

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of the adjacent villages, alarmed by the unusual sound of the bells, accompanied

(as was the custom in many parts of Italy on all festive occasions) by the discharge of firearms, imagined that some disturbance

must have broken out in the city, and began to feel no little anxiety for those of their relations and friends who were absent at the fair.

Some, indeed, had already returned, but these were as much at a loss as the rest; for when they came away they had seen no symptoms of a riot,

neither had they heard of any extraordinary cause of rejoicing. Others, again, had left the city, and were in the act of returning homewards,

when their steps were arrested by these noises; and of these, some whose prudence was stronger than their curiosity only hurried home the faster,

whilst others turned back to investigate the cause. These, however, tarried so long to gaze at the wondrous sight, to hear its history,

and to see the marvelous effects that followed, that the public anxiety of the neighborhood was still unrelieved.

At length, at a very late hour

of the night, some few stragglers returned, and told so strange a tale, that long before daybreak on the following morning multitudes of the

country people might be seen taking advantage of the day of rest (it was the Fourth Sunday after Easter) and hurrying towards the town to see

and inquire for themselves. And not only the strong and the active, but even the aged and infirm, the dumb and the blind, the lame, the maimed,

and many others, came or were brought to this new pool of Bethsaida; for it was part of the intelligence which reached them that many persons

had been miraculously healed of their infirmities in the presence of this Madonna. So great was the number of these miraculous cures,

that with a methodical caution and prudence most unusual in a Catholic country, and at a time when Protestantism was yet unknown,

a notary was appointed to register the principal cases, and to have them attested by the signatures of competent witnesses,

and of the very parties themselves. This register was begun on the second day after the Apparition—i.e. on April 27, and continued until August 14.

It contains the narration of 171 reputed miracles, which had taken place during this period of 110 days; and it was stopped at last,

not because the marvels had ceased, but because enough had now been done to silence the mouths of the most obstinate of gainsayers,

and to establish the right of this picture to be considered an Immagine miracolosa.

At length, at a very late hour

of the night, some few stragglers returned, and told so strange a tale, that long before daybreak on the following morning multitudes of the

country people might be seen taking advantage of the day of rest (it was the Fourth Sunday after Easter) and hurrying towards the town to see

and inquire for themselves. And not only the strong and the active, but even the aged and infirm, the dumb and the blind, the lame, the maimed,

and many others, came or were brought to this new pool of Bethsaida; for it was part of the intelligence which reached them that many persons

had been miraculously healed of their infirmities in the presence of this Madonna. So great was the number of these miraculous cures,

that with a methodical caution and prudence most unusual in a Catholic country, and at a time when Protestantism was yet unknown,

a notary was appointed to register the principal cases, and to have them attested by the signatures of competent witnesses,

and of the very parties themselves. This register was begun on the second day after the Apparition—i.e. on April 27, and continued until August 14.

It contains the narration of 171 reputed miracles, which had taken place during this period of 110 days; and it was stopped at last,

not because the marvels had ceased, but because enough had now been done to silence the mouths of the most obstinate of gainsayers,

and to establish the right of this picture to be considered an Immagine miracolosa.

But it is time that we should inquire somewhat more particularly whence this picture had really been brought, and by what means.

The inhabitants of Genazzano would fain believe that it was the work of angels and had been brought from Heaven, and for this reason they had

given it the name of the Madonna del Paradiso. It was no welcome news to them, therefore, a few days afterwards, to be told that two

strangers from a foreign land had just arrived from Rome, who professed to know the picture, and to be able to tell its history.

One of these strangers was a Slavonian, the other an Albanian; and the story which they told was this:

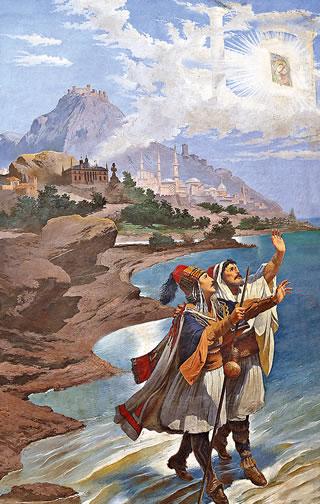

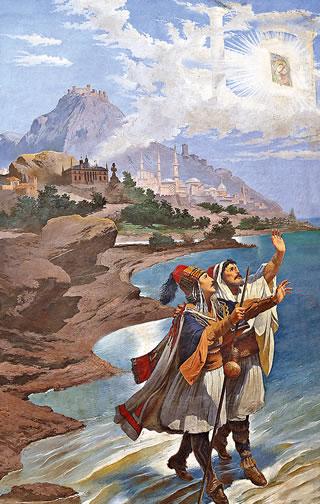

They had been residing together in Scutari, a city of Albania, on the eastern coast of the Adriatic, about twenty miles distant

from the sea. On a little hill outside that city there was a church, in which this Madonna—painted upon the wall—was well known, and much venerated,

as the Madonna del Buon Officio. It was a picture to which there had always been a very great devotion; and lately, in the disturbed

miserable condition of the country, the inhabitants had been more than usually frequent in their visits to it, entreating the Madonna's

interference to defend them from their dangerous enemies, the Turks, who, they had reason to apprehend, were meditating a fresh invasion,

and who, as a matter of fact, did, not many years afterwards, lay waste the whole country, and destroy many cities with fire and sword.

Numbers of the citizens had already fled from the impending calamity; and, as contemporary historians tell us, took refuge, some in Venice,

others in different cities of Romagna (an area of northeastern Italy comprising the cities of Ravenna, Rimini, San Marino, etc.—to the south of

Venice). Amongst the rest, our two strangers at length determined to expatriate themselves like their neighbors; but before doing so,

they went out to bid a last farewell to their favorite shrine, and to pray the Mother of God that as She with Her Divine Son had been forced

to flee from the face of one of the kings of the earth who was plotting mischief against Them, so She would vouchsafe to guide and accompany

these Her humble clients, in their no less compulsory flight.

Whilst they were yet praying the picture disappeared from their sight, and in its stead a white cloud seemed to detach itself

from the wall, to float through the air and to pass out through the doors of the church. Attracted by an impulse which they could not resist,

they followed; presently they found themselves caught up in some mysterious manner along with it, and carried forward in its company.

The manner of their transit who shall explain, save He Who alone can tell how the Angel of the Lord set Habacuc in Babylon over the lion's den

where Daniel was imprisoned, in the force of His Spirit

(Dan. 15: 35), and how He presently set him again in his own place in Judea;

or how, when Philip and the eunuch were come up out of the water, the Spirit of the Lord took away Philip, and the eunuch saw him no more;

and he went on his way, rejoicing, but Philip was found at Azotus

(Acts 8: 36, 40). The men themselves could only testify that

they had been transported—they knew not how—from one place to another; that they had been taken across the Adriatic, whose waves had borne

them up, as the Sea of Galilee had borne St. Peter when Jesus bade him come to Him upon the waters; that, as evening drew on, that which

had seemed a pillar of cloud by day became, as it were, a pillar of fire; and that finally, when they had been brought to the gates of Rome,

it entirely disappeared.

Entered into the Eternal City,

the travelers sought diligently for traces of their lost guide; they went from one church to another,

inquiring for the picture which they had watched so long, and then so suddenly lost sight of; but all their inquiries were in vain.

At length, at the end of two or three days, they heard of a picture having appeared in a very strange way at Genazzano, and that its appearance

was followed by many miracles. Immediately they set out to visit it; there they recognized it and proclaimed its identity.

However, the people of Genazzano lent no willing ear to this strange history—it detracted somewhat from the heavenly origin

which they would have assigned to their newly-gotten treasure and it gave them some uneasiness too as to the ultimate security

of their possession of it; for, should this story be authenticated, the picture might one day be reclaimed and carried away.

In the course of a few days, however, as the story got noised abroad, other Albanians, who were scattered abroad in different parts of Italy,

came to see it; and these too confirmed its identity. At a later date, this fact was still more clearly ascertained

(as in the somewhat similar case of the Holy House of Loreto) by the testimony of persons who spoke upon oath,

not only to the exact shape and size, as corresponding to a blank space that was then still to be seen upon the

walls of the church at Scutari, but also to the coloring and style of art, as precisely the same with that which characterized

all the other parts of the church. For it must be remembered that this was no painting executed upon board or canvas, and thus

capable of easy removal, and leaving no trace behind—it was a mere fresco upon a very thin coating of plaster, which no human skill

could have detached from the wall in a single piece, still less have transported from one place to another without injury.

Entered into the Eternal City,

the travelers sought diligently for traces of their lost guide; they went from one church to another,

inquiring for the picture which they had watched so long, and then so suddenly lost sight of; but all their inquiries were in vain.

At length, at the end of two or three days, they heard of a picture having appeared in a very strange way at Genazzano, and that its appearance

was followed by many miracles. Immediately they set out to visit it; there they recognized it and proclaimed its identity.

However, the people of Genazzano lent no willing ear to this strange history—it detracted somewhat from the heavenly origin

which they would have assigned to their newly-gotten treasure and it gave them some uneasiness too as to the ultimate security

of their possession of it; for, should this story be authenticated, the picture might one day be reclaimed and carried away.

In the course of a few days, however, as the story got noised abroad, other Albanians, who were scattered abroad in different parts of Italy,

came to see it; and these too confirmed its identity. At a later date, this fact was still more clearly ascertained

(as in the somewhat similar case of the Holy House of Loreto) by the testimony of persons who spoke upon oath,

not only to the exact shape and size, as corresponding to a blank space that was then still to be seen upon the

walls of the church at Scutari, but also to the coloring and style of art, as precisely the same with that which characterized

all the other parts of the church. For it must be remembered that this was no painting executed upon board or canvas, and thus

capable of easy removal, and leaving no trace behind—it was a mere fresco upon a very thin coating of plaster, which no human skill

could have detached from the wall in a single piece, still less have transported from one place to another without injury.

But to adhere more closely to the chronological order of our facts, it is necessary that we should return to Rome.

It was scarcely possible that so marvelous a story, circulated in the immediate neighborhood of the Holy See, should fail to attract

the attention of that ever-watchful, jealous tribunal. The translation of the picture is said to have taken place late on the evening

of the 25th of April; on the 15th of May, and following days, the names of certain Albanians appear in the register which has been

already mentioned, as having received remarkable grazie at the shrine, and these were they who confirmed one part of the strangers'

tale by identifying the picture; and before the middle of July, we find Pope Paul II sending two bishops to examine upon the very spot into

all the circumstances of the case. The Bishop of Palestrina, whose duty it would naturally have been to institute this examination,

was Cardinal Cortin, a Frenchman; but as he was absent at Avignon, the Pope appointed in his stead another French bishop,

who happened to be in Rome, and must have been well known to the Cardinal, being the Bishop of Gap in Dauphiny, Msgr. Gaucer;

and with him was joined Msgr. Nicolo de Crucibus, Bishop of Lesina, one of the islands in the Adriatic near the coast of Dalmatia,

whose familiarity as well with the language as with the localities could not fail to be of the utmost service in the investigation

of this matter. The mission of these bishops is not only recorded by contemporary writers (e.g. M. Canesius, in his Life of Pope Paul II,

written in the year 1469), it is also curiously attested by the records of the Papal Treasury, which are still extant, and where we read,

under the date of the 24th of July of that year, an item of 22 florins and 60 bolognini paid for the expenses of two bishops

sent to Genazzano.

It is much to be regretted that the report which these bishops presented upon their return to Rome has nowhere been preserved to us;

its general character, however, is unmistakable, if we consider the facts which followed. Had not their report been favorable,

the register of miracles would not have been continued, as we know it was, until the middle of the succeeding month,

and then its separate sheets collected together, and the whole copied de novo into a single volume by another notary,

with a title in which the miraculous appearance of the picture is expressly mentioned. Again, had not their report been favorable,

those two strangers, who would then have been convicted of imposture, could not have dared to establish themselves, as they undoubtedly did,

in the very town which they had attempted to deceive. (The family of the Albanian remained for centuries; the other became extinct.)

But above all, had not their report been favorable, the work of the new church would not have been resumed and completed in less than

three years; and then bearing among its ornaments inscriptions, paintings, and sculptures, many of which still remain, and all distinctly

commemorate the same wonderful story.

The entire history of this sanctuary, and of the miracles which have been wrought there, of the devotional visits of Popes,

Cardinals, and other princes, and of the offerings which they have sent or left behind them, is very interesting.

The visit of Pope Urban VIII is specially worth mentioning, because that Pope set his face so resolutely against

the sanctioning in any way of miraculous stories resting on no sufficient foundation; yet he came to this church in 1630

on purpose that he might pray before this picture for the averting of the plague, then raging in other parts of Italy,

from his own dominions. We may add also that in 1777 the Congregation of Rites approved a proper Office, commemorating this history,

to be used by all the Augustinian Order; and that the devotion towards the picture is very far from having died away,

as sometimes happens by the lapse of years.

It has always been a favorite place of pilgrimage for the ecclesiastical students in the English College at Rome,

and Cardinal Acton had a special devotion towards it. On occasion of his visit to it in the Autumn of 1845, he met with an accident

which might well have proved fatal both to himself and his companions. He was traveling from Palestrina with his chaplain and servants,

and three students of the English College (a party of eight in all), when the carriage was upset in a very dangerous part of the road.

Carriage, horses, and passengers were precipitated over a bank to the depth of twenty feet;

It has always been a favorite place of pilgrimage for the ecclesiastical students in the English College at Rome,

and Cardinal Acton had a special devotion towards it. On occasion of his visit to it in the Autumn of 1845, he met with an accident

which might well have proved fatal both to himself and his companions. He was traveling from Palestrina with his chaplain and servants,

and three students of the English College (a party of eight in all), when the carriage was upset in a very dangerous part of the road.

Carriage, horses, and passengers were precipitated over a bank to the depth of twenty feet; yet,

as one of the party writes,

not one of us had so much as a scratch, as far as I know, and I never heard mention of injury to anyone, except that the butler,

who was more frightened than hurt, complained of being much shaken. Of course, he and the others outside were flung some way into the field;

we who were inside fell on one another, the Cardinal being immediately below me. The carriage windows were thrown up by the fall,

but were unbroken until men came and broke them to drag us out. The carriage was not much injured; some of the iron-work twisted,

and the pole broken, which caused a deep flesh-wound in one of the horses. We walked on, saying the Rosary, to the neighboring town,

where the Bishop received us, and sent us on to Genazzano. On our arrival there, the Rector and students and the religious community

all joined us in the Te Deum, which was repeated on the following morning, for the miraculous deliverance which a good God had given us.

The Cardinal had a copy of the painting executed, which he always retained for his own private devotion,

and which is now in the sacristy of the Church of Our Lady of the Angels, Stoke-upon-Trent. Another copy, or rather a very beautiful

painting (by Seitz), suggested by it, and retaining the same general idea and attitude of the Mother and Child, is in the chapel

of the Convent of St. Catharine, at Clifton. Very many copies may be seen, not only in the churches of Rome and other states of Italy,

but in Spain and Portugal, in Istria (a peninsula now shared by Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia) and Dalmatia, and even in Africa and America.

As to the title of this painting, it was for some time a subject of considerable dispute, some wishing to retain that which had been

given at first by the devotion of the people—Madonna del Paradiso; others again, advocating the more historical

description—Madonna da Scutari. Since the beginning of the 17th century, however, the revival of the ancient

title—Our Lady of Good Counsel—has universally prevailed; and those of our readers who are familiar either with the

picture itself or with any of its copies, will agree with us in considering it a most happy selection. There is something in the

attitude of the Mother and Child that renders the title particularly appropriate and impressive.

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

Genazzano is a town of some importance in the diocese of Palestrina, very prettily situated on the left of the high road to Naples,

at a distance of about thirty miles to the south-east of Rome. From time immemorial, the Feast of St. Mark the Evangelist was celebrated

there as a very special holiday; in fact, it was the day of the great fair or market of the year. Moreover, there was a very old church

in the city, dedicated to the Madonna of Good Counsel—built, as it would appear, upon a part of the territory that Pope Sixtus III

had conveyed as an endowment to St. Mary Major's in Rome, on the occasion which has been already mentioned (in

Issue No. 189) of his rebuilding that Basilica.

Genazzano is a town of some importance in the diocese of Palestrina, very prettily situated on the left of the high road to Naples,

at a distance of about thirty miles to the south-east of Rome. From time immemorial, the Feast of St. Mark the Evangelist was celebrated

there as a very special holiday; in fact, it was the day of the great fair or market of the year. Moreover, there was a very old church

in the city, dedicated to the Madonna of Good Counsel—built, as it would appear, upon a part of the territory that Pope Sixtus III

had conveyed as an endowment to St. Mary Major's in Rome, on the occasion which has been already mentioned (in

Issue No. 189) of his rebuilding that Basilica. Matters were in this state in

the spring of 1467. On Saturday, April 25, in that year, the usual fair had been held; crowds of people had passed and repassed the old church,

and the imperfect walls of the new; and we cannot doubt but that some at least amongst those who saw them had begun to mock, saying,

Matters were in this state in

the spring of 1467. On Saturday, April 25, in that year, the usual fair had been held; crowds of people had passed and repassed the old church,

and the imperfect walls of the new; and we cannot doubt but that some at least amongst those who saw them had begun to mock, saying,

At length, at a very late hour

of the night, some few stragglers returned, and told so strange a tale, that long before daybreak on the following morning multitudes of the

country people might be seen taking advantage of the day of rest (it was the Fourth Sunday after Easter) and hurrying towards the town to see

and inquire for themselves. And not only the strong and the active, but even the aged and infirm, the dumb and the blind, the lame, the maimed,

and many others, came or were brought to this new pool of Bethsaida; for it was part of the intelligence which reached them that many persons

had been miraculously healed of their infirmities in the presence of this Madonna. So great was the number of these miraculous cures,

that with a methodical caution and prudence most unusual in a Catholic country, and at a time when Protestantism was yet unknown,

a notary was appointed to register the principal cases, and to have them attested by the signatures of competent witnesses,

and of the very parties themselves. This register was begun on the second day after the Apparition—i.e. on April 27, and continued until August 14.

It contains the narration of 171 reputed miracles, which had taken place during this period of 110 days; and it was stopped at last,

not because the marvels had ceased, but because enough had now been done to silence the mouths of the most obstinate of gainsayers,

and to establish the right of this picture to be considered an Immagine miracolosa.

At length, at a very late hour

of the night, some few stragglers returned, and told so strange a tale, that long before daybreak on the following morning multitudes of the

country people might be seen taking advantage of the day of rest (it was the Fourth Sunday after Easter) and hurrying towards the town to see

and inquire for themselves. And not only the strong and the active, but even the aged and infirm, the dumb and the blind, the lame, the maimed,

and many others, came or were brought to this new pool of Bethsaida; for it was part of the intelligence which reached them that many persons

had been miraculously healed of their infirmities in the presence of this Madonna. So great was the number of these miraculous cures,

that with a methodical caution and prudence most unusual in a Catholic country, and at a time when Protestantism was yet unknown,

a notary was appointed to register the principal cases, and to have them attested by the signatures of competent witnesses,

and of the very parties themselves. This register was begun on the second day after the Apparition—i.e. on April 27, and continued until August 14.

It contains the narration of 171 reputed miracles, which had taken place during this period of 110 days; and it was stopped at last,

not because the marvels had ceased, but because enough had now been done to silence the mouths of the most obstinate of gainsayers,

and to establish the right of this picture to be considered an Immagine miracolosa. Entered into the Eternal City,

the travelers sought diligently for traces of their lost guide; they went from one church to another,

inquiring for the picture which they had watched so long, and then so suddenly lost sight of; but all their inquiries were in vain.

At length, at the end of two or three days, they heard of a picture having appeared in a very strange way at Genazzano, and that its appearance

was followed by many miracles. Immediately they set out to visit it; there they recognized it and proclaimed its identity.

However, the people of Genazzano lent no willing ear to this strange history—it detracted somewhat from the heavenly origin

which they would have assigned to their newly-gotten treasure and it gave them some uneasiness too as to the ultimate security

of their possession of it; for, should this story be authenticated, the picture might one day be reclaimed and carried away.

In the course of a few days, however, as the story got noised abroad, other Albanians, who were scattered abroad in different parts of Italy,

came to see it; and these too confirmed its identity. At a later date, this fact was still more clearly ascertained

(as in the somewhat similar case of the Holy House of Loreto) by the testimony of persons who spoke upon oath,

not only to the exact shape and size, as corresponding to a blank space that was then still to be seen upon the

walls of the church at Scutari, but also to the coloring and style of art, as precisely the same with that which characterized

all the other parts of the church. For it must be remembered that this was no painting executed upon board or canvas, and thus

capable of easy removal, and leaving no trace behind—it was a mere fresco upon a very thin coating of plaster, which no human skill

could have detached from the wall in a single piece, still less have transported from one place to another without injury.

Entered into the Eternal City,

the travelers sought diligently for traces of their lost guide; they went from one church to another,

inquiring for the picture which they had watched so long, and then so suddenly lost sight of; but all their inquiries were in vain.

At length, at the end of two or three days, they heard of a picture having appeared in a very strange way at Genazzano, and that its appearance

was followed by many miracles. Immediately they set out to visit it; there they recognized it and proclaimed its identity.

However, the people of Genazzano lent no willing ear to this strange history—it detracted somewhat from the heavenly origin

which they would have assigned to their newly-gotten treasure and it gave them some uneasiness too as to the ultimate security

of their possession of it; for, should this story be authenticated, the picture might one day be reclaimed and carried away.

In the course of a few days, however, as the story got noised abroad, other Albanians, who were scattered abroad in different parts of Italy,

came to see it; and these too confirmed its identity. At a later date, this fact was still more clearly ascertained

(as in the somewhat similar case of the Holy House of Loreto) by the testimony of persons who spoke upon oath,

not only to the exact shape and size, as corresponding to a blank space that was then still to be seen upon the

walls of the church at Scutari, but also to the coloring and style of art, as precisely the same with that which characterized

all the other parts of the church. For it must be remembered that this was no painting executed upon board or canvas, and thus

capable of easy removal, and leaving no trace behind—it was a mere fresco upon a very thin coating of plaster, which no human skill

could have detached from the wall in a single piece, still less have transported from one place to another without injury. It has always been a favorite place of pilgrimage for the ecclesiastical students in the English College at Rome,

and Cardinal Acton had a special devotion towards it. On occasion of his visit to it in the Autumn of 1845, he met with an accident

which might well have proved fatal both to himself and his companions. He was traveling from Palestrina with his chaplain and servants,

and three students of the English College (a party of eight in all), when the carriage was upset in a very dangerous part of the road.

Carriage, horses, and passengers were precipitated over a bank to the depth of twenty feet;

It has always been a favorite place of pilgrimage for the ecclesiastical students in the English College at Rome,

and Cardinal Acton had a special devotion towards it. On occasion of his visit to it in the Autumn of 1845, he met with an accident

which might well have proved fatal both to himself and his companions. He was traveling from Palestrina with his chaplain and servants,

and three students of the English College (a party of eight in all), when the carriage was upset in a very dangerous part of the road.

Carriage, horses, and passengers were precipitated over a bank to the depth of twenty feet;