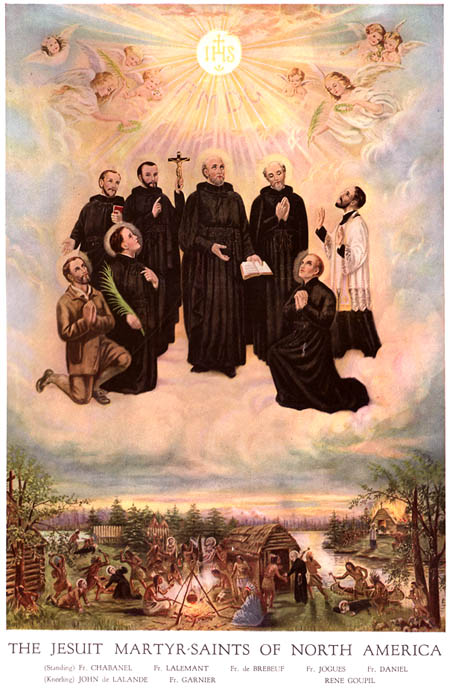

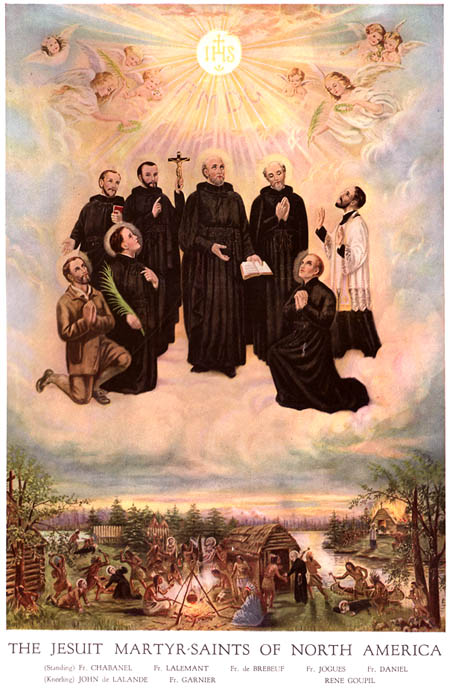

The North American Martyrs (†1642-9; Feast – September 26)

Part I – Mission to the Hurons

Precious to God are His missionaries, those heroic souls who, in imitation of the Twelve Apostles,

Precious to God are His missionaries, those heroic souls who, in imitation of the Twelve Apostles, go forth and teach all nations

the way of salvation. Yet, in this present age of heretical religious tolerance and indifferentism, it is unfortunate,

but not surprising, to find the ancient apostolic spirit gone. What need is there for missionaries if, as many today erroneously contend,

the only requirement for salvation is personal sincerity in whatever one believes? Indeed, the driving force behind all genuine

apostolic labor is Our Lord's command to teach

every human creature the truths necessary for their salvation.

Our Lord added to this commission, He that believeth and is baptized, shall be saved: but he that believeth not shall be condemned.

Members of the Society of Jesus who dedicated themselves to the conversion of the American Indians took Christ's words

literally. They journeyed from comfortable Renaissance France to the frontiers of North America that they might preach and baptize.

After pouring the saving waters of Baptism on a dying Indian child, Saint Jean de Brébeuf, the great pioneer of this mission,

exclaimed with joy, For this one single occasion I would travel all the way from France; I would cross the great ocean to win

one little soul for Our Lord!

And so pleased was God with the genuine zeal and the extraordinary sacrifices of these

generous apostles that He bestowed upon Father Brébeuf and seven of his fellow missionaries the glorious crown of martyrdom.

The following is the incredible tale of the eight North American Martyrs:

The Society of Jesus had been founded by Saint Ignatius of Loyola during the turbulent times following the

Protestant Revolution. By the dawning of the seventeenth century the Jesuits had won renown as zealous missionaries and

ardent defenders of the Catholic Faith. The Order was still at the peak of its power, prestige, and holiness when a new

mission field began to unfold. Catholic France was beginning to colonize North America, and the vast untamed regions of

the New World were inhabited by pagan natives who had never before been evangelized.

FATHER JEAN DE BRÉBEUF, a giant of a man in stature and in holiness, was destined by God to be the impetus,

the strength and the inspiration of the new Jesuit mission efforts in North America.

Early Years

Brébeuf was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, March 25, 1593, at Condé, about seven miles from Sainte Lô in

Eastern Normandy. In his youth he was a strong, outdoor-loving boy and an industrious worker on his family's extensive farm.

The young Brébeuf towered above his peers. He often referred to his family name, which means "ox" in French, and jokingly

professed that he was meant only to carry heavy burdens. But Jean had been blessed with a pious nature and a good mind

as well as broad shoulders, and instead of gathering crops from the fields of Normandy, it was God's will that he should

reap the harvest of souls abounding in New France. He responded to God's calling and was received into the Society of Jesus in 1617.

Before long, he became very ill. The sickness reduced Jean's huge frame to that of a skeleton, and it was believed that the young

Jesuit had not long to live. Following his ordination to the Priesthood in 1622, however, his health seemed to return miraculously,

and he soon regained his former vigor.

The newly ordained Priest had often dreamed of becoming a missionary, and upon recovering his health,

his desires of being sent to the New World increased. He was very much aware of the recent attempts to evangelize the

North American Indians. Through the assistance of the devout Catholic explorer Samuel de Champlain, the Franciscan

Recollets had arrived at Québec in 1615. The Recollets had labored heroically for over ten years, but had encountered

many problems from the rabidly anti-Catholic Huguenots (French Calvinists), who controlled the settlement.

In addition to this, the Recollets were far too few in number to effect any lasting result in the conversion of the savages.

Therefore, in 1624 they had petitioned help from the Jesuits, who were eager to accept the invitation to that part of

North American known as "New France."

Arrival in the New World

It was in June, 1625, that the future martyr first set foot on the shores of the New World. The thirty-two year old missionary was

the youngest of the three Jesuit priests on the expedition. Upon arrival they joined the Recollets at their little friary on the

Saint Charles River, not far from the settlement of Québec.

It was in June, 1625, that the future martyr first set foot on the shores of the New World. The thirty-two year old missionary was

the youngest of the three Jesuit priests on the expedition. Upon arrival they joined the Recollets at their little friary on the

Saint Charles River, not far from the settlement of Québec.

Brébeuf knew that his formal education offered little, if any, of the training needed for the work he was about to

undertake. He spent his first days in New France acquiring from the Recollets as much knowledge as he could about the savages

he had come to convert. Among other things, he learned that the largest Indian nation was the Algonquin, which inhabited an

extensive territory, including Nova Scotia, and the area north of the Saint Lawrence River. They were a nomadic people,

and it was clear to the Recollets that such tribes as the Algonquins could be converted only when induced to stop their wandering.

There was a good possibility, however, of evangelizing the Hurons, who lived in permanent

well-fortified settlements in the distant western regions north of Lake Ontario. The Hurons, thus named by the French expression

hure, meaning a disheveled head of hair, called themselves the Wyandot nation. They were more docile than

the Indians who frequented Québec. Their population was about thirty thousand.

Greatly impressed were the Indians with the size and bearing of the bearded "Blackrobe" who smiled so amiably at them.

Unable to properly pronounce his name, they dubbed him Echon, and Echon he would be from that time on among

all the Indians.

Father Brébeuf spent the following winter with a tribe of Algonquins known as the Montagnais,

in order to grow more accustomed to the Indian way of living. During this five-month hunting venture the saint beheld

everything the Recollets had related about these primitive people. The suffocating fires and foul odors within made the

huts most uncomfortable. The savages were rough, impatient, and thoroughly given over to every impurity. Their "divinities"

were the sun, the moon, and almost any material object. Sorcerers led wild feasts and orgies to appease the evil spirits,

and superstition accompanied all that they did. Father Brébeuf, convinced of Satan's dominion over these poor souls,

prayed fervently for their conversion to the True Faith.

To the Hurons

Rather than dampening his spirit, the events of Father Jean's winter sojourn only increased his already ardent zeal. His desire

now was to live with the Hurons. To his great delight, in the summer of 1626, Father Brébeuf and a Franciscan Recollet,

Father Joseph de la Roche Daillon, were selected for the important assignment of establishing a Mission in the midst of

this distant tribe. In July, the two priests met a Huron trading party at Cap de la Victoire, and departed with them on

their homeward journey to Huronia.

With Echon, the Hurons were very pleased. With the diligence and zeal of a disciplined Religious,

he paddled the canoe and shouldered heavy burdens as well as any Indian brave. In order to gain the advantage in converting them,

it was important to win the savages' respect on the journey for, as Father Brébeuf would one day write to inform future missionaries,

...the savages will retain the same opinion of you in their own country that they will have formed on the way...

After they had navigated the Ottawa River, Lake Nipissing, the French River, and numerous smaller waterways in between,

the weary travelers, having covered nine hundred miles in one month, finally arrived at the land of the Hurons.

The Huron villages offered a striking contrast to the crude, temporary dwellings Father Brébeuf had seen

while living with the nomadic Algonquins. A typical Huron settlement contained many well-built cabins, and was usually

surrounded by a palisade fence. Each cabin or long-house, as it was called, was from thirty to ninety feet long and up

to thirty feet wide. Constructed of poles lashed together and covered with bark, it curved up to a height of about twenty feet.

The Mission

A monumental task confronted Father Brébeuf and those who would one day follow him to the Huron mission.

Great obstacles had to be overcome before an effective apostolate could be launched.

A monumental task confronted Father Brébeuf and those who would one day follow him to the Huron mission.

Great obstacles had to be overcome before an effective apostolate could be launched.

First, the language barrier had to be broken down. This was quite a challenge to any European, especially since

the Indians completely lacked a written language. Moreover, their words were uttered without the use of the lips, and required

voice inflection, as well as sound, to convey their proper meaning. To the untrained ear an Indian sentence resembled nothing

more than a series of guttural grunts. Nor did they have words to describe abstract thoughts. This meant that the truths of

the Faith would have to be taught in terms of material things alone. The Recollets had made remarkable progress in compiling

a valuable list of Huron words and phrases, which gave Father Brébeuf hope that, through perseverance, the language could be mastered.

Then, too, there were the more serious problems of diabolical superstition, sorcery, promiscuity, war, and cannibalism.

It would require more than perseverance alone to deliver these savages from such complete dominance by the powers of Hell.

When Father Daillon was recalled by his Superiors to Québec in 1628, Father Brébeuf remained an entire year longer

among the Hurons, becoming virtually an accepted member of the tribe. Despite the frantic opposition of the demonic "medicine men,"

the saintly missionary aroused the interest of many of the savages in the One True God. As he became more fluent in the Huron language,

he was able to speak at their councils, promising them happiness after death, if they were Baptized.

But towards the end of his third year among the Hurons, Father Brébeuf's great hopes for the future were suddenly dashed.

He received word that Québec had been cut off from all supplies by an English fleet—commanded by the Kirk brothers,

who were little more than marauding pirates—under the flag of the British Protestant Crown. The colony was on the verge

of starvation and there was imminent danger of an English attack. He was ordered to return to Québec as soon as possible.

In obedience to his Superiors, Echon made immediate preparations for his departure. He was keenly disappointed

that he had to leave the Hurons but he accepted the distressing news as the permissive will of God. The seed of the Faith

had been planted and he was certain that, in due season, it would bring forth fruit a hundredfold.

A Brief Interruption, 1629-33

By July 1629, Father Brébeuf was back in Québec, having brought with him a good supply of Huron corn for the

starving colony. More than food was needed, however. Champlain's militia was far too small and ill-equipped to withstand an attack.

The only alternative was to hand over the Catholic settlement to the British. With the assurance of safe passage back to France

for everyone in the colony, Champlain formally surrendered. The threat of starvation and of an English massacre were both over,

but unfortunately, so were the present mission labors in New France. Heartbroken, Brébeuf and the other Religious were forced

to board English ships and to sail the great Atlantic home to France.

Much to the frustration of the British marauders, it was discovered upon returning to England, that their seizure of

Québec had come months after both France and England had signed the Treaty of Susa, which prohibited it. Even then they refused

to relinquish possession of the Catholic settlement. However, thanks to the militant zeal of the redoubtable Samuel Champlain,

who began arming warships to retake the colony, by the spring of 1632, an agreement had been reached allowing the French to

reoccupy Québec.

Meanwhile, Father Brébeuf, in the peace of his daily religious exercises at the College of Rouen,

deepened his inner life through constant prayer and mortification. He also pronounced his final religious vows at this time,

which made him, until death, a son of Saint Ignatius. He added to these solemn vows, the oblation to Our Lord of everything

he possessed, including life itself, if it so pleased God to accept it.

In 1633 he left France for the last time to commence again the labors he had been forced to abandon.

The remaining sixteen years of his life would be spent in the arduous task of evangelizing the savages of New France.

Return to the Missions

At first Father Brébeuf was assigned to labor again among Québec's neighboring savages, the Montagnais, and while his efforts

failed to produce any tangible success, it gave the veteran missionary a chance to teach some of his new assistants the basics

of the apostolate. One of the ablest young missionaries proved to be an intelligent thirty-two year old Jesuit from Dieppe,

FATHER ANTOINE DANIEL. Daniel had studied law before entering the Society of Jesus in 1621. He possessed the inherent qualities

of faith, zeal, and humility, so essential for the formation of a good apostle... and a future martyr.

At first Father Brébeuf was assigned to labor again among Québec's neighboring savages, the Montagnais, and while his efforts

failed to produce any tangible success, it gave the veteran missionary a chance to teach some of his new assistants the basics

of the apostolate. One of the ablest young missionaries proved to be an intelligent thirty-two year old Jesuit from Dieppe,

FATHER ANTOINE DANIEL. Daniel had studied law before entering the Society of Jesus in 1621. He possessed the inherent qualities

of faith, zeal, and humility, so essential for the formation of a good apostle... and a future martyr.

The discomforts of a long journey to Huronia, at this time, were a genuine test of patience for even the most

virtuous among Brébeuf's companions. Thirty days of grueling travel were made especially tiresome by the constant insolence

and cruelty inflicted on the Frenchmen by the extremely irritable savages, still half-sick from a recent epidemic of influenza.

With the completion of their cabin in the village of Ihonataria, the missionaries made more frequent attempts

to teach their prospective converts the Faith. Their crude dwelling became also their temporary chapel, where often they

would invite the villagers to assemble. These meetings were very important and Father Brébeuf wasted no words in his

initial instruction. He wrote: We began our catechism by this memorable truth, that their souls, which are immortal,

all go after death either to Paradise or to Hell... I added that they had the choice during life, to participate after death

in the one or the other—which one, they ought now to consider. Whereupon one honest old man said to me, 'Let him who will go

to the fires of Hell; I want to go to Heaven!' All the others followed, making use of the same answer, and begged us to

show them the way...

But years would elapse before the Hurons would sincerely accept the way

of salvation. For two years,

except for the consolation of baptizing some of the Indian children and the dying, the missionaries had to be content with

simply refuting the bizarre savage superstitious beliefs and explaining, as best they could, the true religion.

Speaking of the mature Hurons, Father Brébeuf said, They know the beauty of the truth, they approve of it,

but they don't embrace it.

Baptism, therefore, was wisely withheld from healthy adults unless the candidate

was proved to be truly steadfast in the Faith and worthy of that holy Sacrament.

The Indian children, however, were quite receptive to what the Blackrobes taught, and soon competed

with one another in answering catechism questions. The youngsters took a special liking to Father Daniel,

who became their teacher. Antoine Daniel, known as Antwen, had made considerable progress in learning the Huron

language and before long had produced a Huron translation of the Our Father, which many of the Indian children learned to recite.

In 1636 Father Daniel returned to Québec with six Huron lads, and established the first school for the instruction of the Huron

children in New France.

Father Brébeuf remained in Huronia tirelessly laboring as both priest and infirmarian for the inhabitants of

Ihonataria and its neighboring villages. In the midst of this rigorous schedule, the Saint somehow found time to record

his experiences with the Hurons. It was a common requirement for the Jesuit missionaries to write detailed reports about

the people they evangelized and the significant events of their missions. These accounts, known as the Jesuit Relations,

were often published to stimulate, among European readers, interest in and enthusiasm for the Jesuit foreign missions.

Father Brébeuf's writings, far from being merely historical or cultural documents, were packed with edifying meditations

and practical advice for future missionaries to the Hurons. He concluded his Relation of July, 1636, with these thoughts:

Jesus Christ is our true greatness; it is He alone and His Cross that should be sought in following after these people.

For if you strive for anything else, you will find nothing but bodily and spiritual affliction. But having found Jesus Christ

in His Cross, you have found the roses in the thorns, sweetness in bitterness, all in nothing.

It was becoming more evident to Echon, at this time, that a very great cross and perhaps and unequaled obstacle

in the path of converting the Hurons would be their fierce enemies, the Iroquois. Iroquois warriors had been

making well-planned forays on unsuspecting villages, particularly in southern Huronia; but the entire Huron nation,

including Ihonataria and other northern settlements, was in a state of alert and fear.

Neither native nor missionary was safe in Huron country. But in spite of such prevailing danger, Echon

had resolved to remain with these Indians, cost what it may, to bring them to a knowledge of the Truth.

August, 1636

Father Brébeuf had not long to wait for the much-needed recruits he had been praying to receive.

Within two years after his return to the Hurons he had five zealous priests laboring with him. Among those selected

by the Jesuit superiors to be Echon's assistants were two priests chosen also by God to be martyrs,

FATHER CHARLES GARNIER and FATHER ISSAC JOGUES.

Charles Garnier, called Ouracha by the Indians, came to Huronia in August, 1636. The Parisian-born Jesuit

was thirty years old at the time and had just been ordained the previous year. Although physically rather frail,

Garnier was to survive fourteen years of exhausting mission efforts among the Hurons and the neighboring Petun tribe.

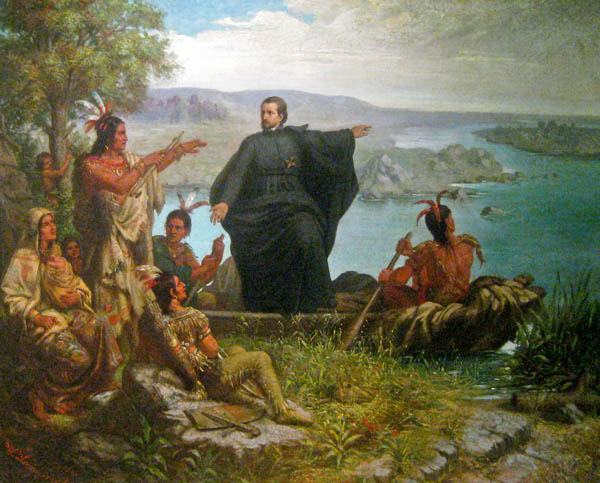

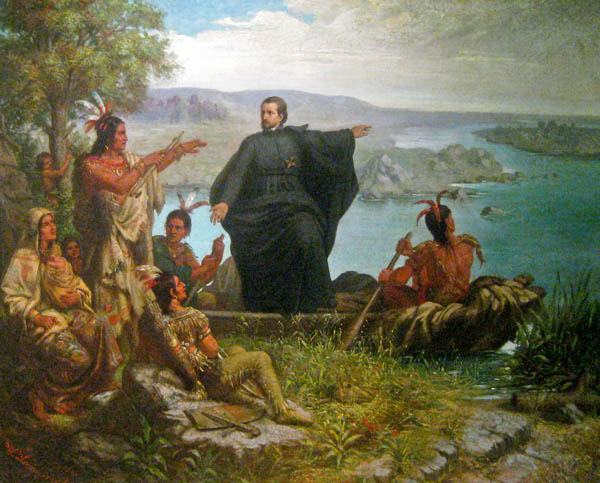

Isaac Jogues (image left), a native Orleans, was twenty-nine when he arrived at the Huron mission in September, 1636—a month

after Garnier. Jogues had entered the Jesuit novitiate at seventeen, and had become a professor of literature before being

selected the missions in Canada. His ordination preceded his departure for the New World by only two months.

Ondessonk, as the Indians named him, was to become an intrepid pioneer who, in addition to working with the Hurons,

would one day teach the Gospel to tribes near Lake Superior and would also become the first apostle to the Iroquois.

Isaac Jogues (image left), a native Orleans, was twenty-nine when he arrived at the Huron mission in September, 1636—a month

after Garnier. Jogues had entered the Jesuit novitiate at seventeen, and had become a professor of literature before being

selected the missions in Canada. His ordination preceded his departure for the New World by only two months.

Ondessonk, as the Indians named him, was to become an intrepid pioneer who, in addition to working with the Hurons,

would one day teach the Gospel to tribes near Lake Superior and would also become the first apostle to the Iroquois.

Echon's new assistants were just getting acclimated to their surroundings in Huronia when the influenza

flared up into epidemic proportions once again. The French had been spared, so far, from contracting the dreadful disease

but they were apprehensive of losing this immunity. A few weeks after his arrival, Father Jogues fell very ill with the

sickness. And soon, one by one, all the French, except Father Brébeuf, were stricken. Brébeuf nursed his patients without

the benefit of medicines. Though some of them, including Father Jogues, were at death's door, all gradually began to recover

after several weeks of confinement in their cabin. That none of the French perished with the contagion was clearly a miracle.

Once recovered, the Jesuits busied themselves in caring for the ailing savages. But the Fathers grew alarmed

when the Indians, instead of expressing their gratitude, began to display signs of suspicion. The savages had been aroused

by their sorcerers, who suspected that the Blackrobes had survived the illness because they were secretly practicing their

own form of sorcery. The medicine men added to this accusation that the Blackrobes had caused the pestilence in the first

place so that the French could thereby kill all the Hurons and take their land.

Mysterious are the ways of God's Providence that He should allow the first years of this mission to coincide

with the devastating malady which was afflicting the Huron nation. The Jesuits were undoubtedly confronted with problems

as a result of the disease, but ultimately good was being derived from it.

Most important was the fact that the missionaries were populating Heaven with the souls of the dying savages

whom they baptized. Also, surrounded with death as they were, the Indians were less preoccupied with temporal concerns

and more willing to listen to Echon and his fellow Blackrobes teach them about the eternity of happiness or misery

that awaits all men after death.

Echon, during this period, was often allowed to address the Huron councils. He proposed that they

abandon their superstitious practices and begin to obey the commandments of the "One-Who-made-all." Even though the sorcerers

continued viciously to oppose the FathersEchon, with his logic and eloquence, won many of the chiefs and elder Hurons,

who at least verbally agreed to obey the commandments of the Blackrobe's God. Such promises, although encouraging,

were by no means genuine conversions. For, while the savages longed for the joys of Heaven and feared eternal hellfire,

they still were not ready to accept the Catholic Faith nor its morality.

By the early months of 1637 the epidemic had greatly receded and with it the haranguing of the sorcerers

and the suspicions of the other natives.

By the summer, significant progress was made in overcoming the superstitious misconception about the

Holy Sacrament of Baptism. First, a prominent Huron, Tsiouendaenthana, middle-aged chief of Ihonataria,

renounced all immoral and superstitious practices and asked to be received into the Faith of the Blackrobes.

In June, without dropping dead on the spot, as many of the savages believed he would, he was baptized and given the name of Peter.

Two months later, at Ossossané, a young chieftan about thirty-five years old, Chihwatenhwa, approached Echon and asked

to be baptized. Father Brébeuf was astonished to find that Chihwatenhwa had but one wife and had been living a virtuous life

separated from the feasts, orgies, and superstitious beliefs of the Indian world surrounding him. The new convert received

the name Joseph. Both of these men became an edification to the missionaries and a source of great wonder to their fellow Hurons.

They took their Faith very seriously. Father Brébeuf had anticipated for a long time the first fruits of the Huron mission,

and at last they had been harvested.

New Dangers

The sweetness of these victories was short-lived, however, for by early autumn the influenza was again raging

among the Hurons. This time those who suspected the cause of the disease to be the Jesuits exhibited outright hostility

toward them. Father Brébeuf bade his companions to be ready for death at any moment and ordered a Novena of Masses

to be started in honor of St. Joseph. He composed a letter to be sent to his superior in Québec. Dated October 28, 1637,

it reads in part: We are perhaps upon the point of shedding our blood and of sacrificing our lives in the service of our

Good Master, Jesus Christ. It seems that His Goodness is willing to accept this sacrifice from me for the expiation of my

great innumerable sins, and to crown from this hour forward the past services and the great and ardent desires of all our

priests who are here... But we are all grieved over this—that these barbarians, through their own malice, are closing

the door to the Gospel and to Grace… Whatever conclusion they reach, and whatever treatment they accord us, we will try,

by the Grace of Our Lord, to endure it patiently for His service. It is a singular favor that His Goodness gives us,

to allow us to endure something for the love of Him...

That same day Echon, following an Indian tradition of feasting just prior to one's own death,

invited the savages to his death banquet. The Jesuit residence was filled to capacity by a mob of hungry Hurons,

who glutted themselves with sagamité while Echon chanted his death song in the Huron tongue.

He vividly depicted the eternal joys of the blessed in Heaven and the torments of the damned in Hell—a death chant

the savages had never heard before. The Indians were moved by this convincing presentation and departed from the

feast with contented stomachs but troubled minds. Suddenly, their condemnation of the Blackrobes had become indecisive.

The Fathers, knowing that any display of fear on their part would be a sign of guilt, went about their

duties in the village as if no serious dangers existed. They were neither molested nor threatened in any way.

In fact, when the Novena to St. Joseph was completed a week later, a tranquility pervaded Huronia, which even the savages

could not help but notice. The Blackrobes marveled at God's protection and the powerful intercession of their faithful guardian,

St. Joseph.

Within a few months the epidemic had finally subsided and cases of harassment had become rare.

Any such incidents were usually the acts of crazed sorcerers rather than of dangerous mobs. Moreover, some of the Huron chiefs,

intrigued by the mysteries of the Catholic Faith, began to invite the Blackrobes to councils for the sole purpose of

discussing religion. Eager to advance the message of salvation, the Blackrobes, in turn, held special feasts wherein

they preached to throngs of savages. Although most of the listeners came as a result of curiosity, a small but noticeable element,

including chiefs and elders, was becoming genuinely interested in what the missionaries had to say. Before long,

a few of the Hurons at Ossossané were asking the Blackrobes for private instructions in the Faith, and the number of

adult baptisms began to increase.

A Growing Apostolate

This unexpected turn of events at Ossossané encouraged Echon to extend the mission to other Huron settlements. Echon

had often petitioned to be relieved of the great responsibility of being Superior, preferring the life of a simple missionary.

Besides, with the pioneer days of the mission drawing to a close, he humbly urged that a more qualified leader should be sent

to command the mission. Brébeuf was therefore pleased when Father Jerome Lalemant was appointed to succeed him as Superior in

August, 1638.

This unexpected turn of events at Ossossané encouraged Echon to extend the mission to other Huron settlements. Echon

had often petitioned to be relieved of the great responsibility of being Superior, preferring the life of a simple missionary.

Besides, with the pioneer days of the mission drawing to a close, he humbly urged that a more qualified leader should be sent

to command the mission. Brébeuf was therefore pleased when Father Jerome Lalemant was appointed to succeed him as Superior in

August, 1638.

Lalemant was the uncle of the future martyr, GABRIEL LALEMANT, who would join the Jesuits in New France

ten years later. The new Superior was a zealous missionary and an able administrator. While he depended much on the invaluable

advice of the veteran Brébeuf, Lalemant brought with him to the mission a few innovations.

The Jesuits had always had laymen to help them with the manual labor in their missions, but under Lalemant's

direction a new force of devoted volunteers emerged, called donnés, or oblates. Bound by promises of poverty,

chastity, and obedience, but not by the religious vows of the Society, the donnés became a tremendous asset,

for in addition to offering their talents as domestic laborers they became auxiliary catechists and missionaries.

Lalemant also introduced the idea of building a French station apart from all Huron villages which could serve as

the mission's headquarters. This first exclusively French settlement in Huronia was called Mission Sainte Marie (image right).

Hardships Increase

War with the Iroquois and disease, however, were taking their toll on the Huron people. A census taken

by the Jesuits revealed that the thirty-two Huron villages were then inhabited by approximately twenty thousand Indians,

a drastic decline from the estimated population of over thirty thousand just four years earlier. In September 1639,

another epidemic arose in the midst of the suffering Huron nation. This time it was the dreadful smallpox.

Within weeks the contagious disease spread to almost every Huron village, leaving hundreds dead in its wake.

The Fathers were consequently suspected, threatened, and even expelled from every village they visited.

Father Brébeuf and all the Jesuit priests in New France sensed that the hardships borne by them thus far

were but a foretaste of the still greater sufferings which were to come. We have sometimes wondered,

wrote Lalemant,

whether we could hope for the conversion of this country without the shedding of blood...

For in the words of the

ancient axiom, The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.

And indeed the years of the Huron mission,

filled as they were with extraordinary sacrifices, were as so many steps along the Way of the Cross,

leading the Jesuit missionaries up the Mount of Calvary, where a chosen few among them would shed their blood

in imitation of Our Lord. (To be continued...)

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Back to Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

Precious to God are His missionaries, those heroic souls who, in imitation of the Twelve Apostles,

Precious to God are His missionaries, those heroic souls who, in imitation of the Twelve Apostles,  It was in June, 1625, that the future martyr first set foot on the shores of the New World. The thirty-two year old missionary was

the youngest of the three Jesuit priests on the expedition. Upon arrival they joined the Recollets at their little friary on the

Saint Charles River, not far from the settlement of Québec.

It was in June, 1625, that the future martyr first set foot on the shores of the New World. The thirty-two year old missionary was

the youngest of the three Jesuit priests on the expedition. Upon arrival they joined the Recollets at their little friary on the

Saint Charles River, not far from the settlement of Québec. A monumental task confronted Father Brébeuf and those who would one day follow him to the Huron mission.

Great obstacles had to be overcome before an effective apostolate could be launched.

A monumental task confronted Father Brébeuf and those who would one day follow him to the Huron mission.

Great obstacles had to be overcome before an effective apostolate could be launched. At first Father Brébeuf was assigned to labor again among Québec's neighboring savages, the Montagnais, and while his efforts

failed to produce any tangible success, it gave the veteran missionary a chance to teach some of his new assistants the basics

of the apostolate. One of the ablest young missionaries proved to be an intelligent thirty-two year old Jesuit from Dieppe,

FATHER ANTOINE DANIEL. Daniel had studied law before entering the Society of Jesus in 1621. He possessed the inherent qualities

of faith, zeal, and humility, so essential for the formation of a good apostle... and a future martyr.

At first Father Brébeuf was assigned to labor again among Québec's neighboring savages, the Montagnais, and while his efforts

failed to produce any tangible success, it gave the veteran missionary a chance to teach some of his new assistants the basics

of the apostolate. One of the ablest young missionaries proved to be an intelligent thirty-two year old Jesuit from Dieppe,

FATHER ANTOINE DANIEL. Daniel had studied law before entering the Society of Jesus in 1621. He possessed the inherent qualities

of faith, zeal, and humility, so essential for the formation of a good apostle... and a future martyr. Isaac Jogues (image left), a native Orleans, was twenty-nine when he arrived at the Huron mission in September, 1636—a month

after Garnier. Jogues had entered the Jesuit novitiate at seventeen, and had become a professor of literature before being

selected the missions in Canada. His ordination preceded his departure for the New World by only two months.

Ondessonk, as the Indians named him, was to become an intrepid pioneer who, in addition to working with the Hurons,

would one day teach the Gospel to tribes near Lake Superior and would also become the first apostle to the Iroquois.

Isaac Jogues (image left), a native Orleans, was twenty-nine when he arrived at the Huron mission in September, 1636—a month

after Garnier. Jogues had entered the Jesuit novitiate at seventeen, and had become a professor of literature before being

selected the missions in Canada. His ordination preceded his departure for the New World by only two months.

Ondessonk, as the Indians named him, was to become an intrepid pioneer who, in addition to working with the Hurons,

would one day teach the Gospel to tribes near Lake Superior and would also become the first apostle to the Iroquois. This unexpected turn of events at Ossossané encouraged Echon to extend the mission to other Huron settlements. Echon

had often petitioned to be relieved of the great responsibility of being Superior, preferring the life of a simple missionary.

Besides, with the pioneer days of the mission drawing to a close, he humbly urged that a more qualified leader should be sent

to command the mission. Brébeuf was therefore pleased when Father Jerome Lalemant was appointed to succeed him as Superior in

August, 1638.

This unexpected turn of events at Ossossané encouraged Echon to extend the mission to other Huron settlements. Echon

had often petitioned to be relieved of the great responsibility of being Superior, preferring the life of a simple missionary.

Besides, with the pioneer days of the mission drawing to a close, he humbly urged that a more qualified leader should be sent

to command the mission. Brébeuf was therefore pleased when Father Jerome Lalemant was appointed to succeed him as Superior in

August, 1638.