Celebrated Sanctuaries of the Madonna

Seventh in a Series

In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author

succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

Madonna della Quercia, Viterbo

At a short distance from the walls of Viterbo, on a spot formerly known as the Campo Grazzano, stands the celebrated Convent of

La Quercia, with its beautiful campanile, rising above the trees which line the road leading to the Porta Santa Lucia.

The church with its adjacent cloister, designed by Bramante, is considered a masterpiece by that artist, and its situation

would seem as if chosen in order to command the most magnificent view. The woody heights of Mount Cimino rise on the south;

on the north appear the town and hills of Montefiascone; the Appenines are on the east; whilst in the opposite direction you

look over a richly variegated country towards the distant Mediterranean. However the site of the convent was not fixed in

consequence of its picturesque beauty; it was determined by what may be called accidental circumstances, unless our readers

are willing to believe that, as is affirmed of so many other sanctuaries of Our Lady, She Herself made choice of the spot whence

She had determined to dispense Her graces.

At a short distance from the walls of Viterbo, on a spot formerly known as the Campo Grazzano, stands the celebrated Convent of

La Quercia, with its beautiful campanile, rising above the trees which line the road leading to the Porta Santa Lucia.

The church with its adjacent cloister, designed by Bramante, is considered a masterpiece by that artist, and its situation

would seem as if chosen in order to command the most magnificent view. The woody heights of Mount Cimino rise on the south;

on the north appear the town and hills of Montefiascone; the Appenines are on the east; whilst in the opposite direction you

look over a richly variegated country towards the distant Mediterranean. However the site of the convent was not fixed in

consequence of its picturesque beauty; it was determined by what may be called accidental circumstances, unless our readers

are willing to believe that, as is affirmed of so many other sanctuaries of Our Lady, She Herself made choice of the spot whence

She had determined to dispense Her graces.

It was in the year 1417, during that lamentable period known as the Great Schism, that a certain artist named

Baptista Juzzante fastened a picture of the Madonna painted on a tile to an oak tree, which then grew on the Campo Grazzano.

The picture represents the half-figure of Our Lady dressed in a crimson vest, and wearing a blue mantle, supporting Her Divine Son,

Who appears in a yellowish-colored tunic, and holds a little bird in His right hand. Baptista is said to have placed it in the tree

by Divine Inspiration,

but in point of fact there was nothing very extraordinary in this circumstance.

Pictures and images of Our Lady were very commonly placed thus for the devotion of wayfarers, like the Virgin of the Oak

at

Norwich, and in some cases have been discovered embedded in the wood, which in process of time has grown over and concealed them

from view.

For several years the picture of which we are speaking did not attract any particular attention, though the peasants,

who sometimes paid their devotions before it on their way to and from the city, affirmed in their simplicity that however often it

was blown down by the wind, it was always replaced uninjured on the oak without the aid of human hands, and they noticed what they

deemed the marvelous way in which the branches of the tree interlaced one another, so as gradually to form a sort of niche,

thoroughly overarching and protecting the Madonna from the wind, rain, and snow. However, it did not long remain undisturbed

in its oaken tabernacle. Not far from the spot, on one of the heights of Mount Cimino, known as Mount Saint Angelo, there live a

hermit named Pier Domenico Alberti. He was a Siennese by birth, but had abandoned the world, and taken up his abode in this solitude,

whence it was his pious custom to come almost daily, in order to pay his devotions before the picture, which was by this time almost

hidden by the luxuriant branches. At last the thought occurred to him of removing it to the chapel of his own hermitage, which he

accordingly did, but that night as he slept, he seemed to see in his dreams the picture hanging, as before, in the tree, and when

he woke he found, to his astonishment, that it was actually gone from the place where he had carefully fixed it the night before.

Hastening to the Campo Grazzano in some perplexity, his wonder was yet further increased on finding the Madonna restored to Her

former position, and supported in the tree by the hands of two angels. With many tears he hastened to implore Our Lady's pardon

for his boldness in having removed Her from Her chosen home, and without openly declaring what had happened, he was from that time

observed constantly to allude to some great treasure which existed between Viterbo and Bagnaia—a treasure, he said, which no one

as yet knew or cared for; and when some of those to whom he thus spoke proposed to go and dig for it, he would shake his head and

tell them their labor would be useless, for that the treasure was not hidden underground.

Meanwhile, some devout women of Viterbo had also discovered the picture, and one of them, named Bartolomea,

conceived such a devout affection for it that, after one day praying before it for a long time, she resolved, as the hermit had done,

to remove it to her own house. But it very soon found its way back to the oak, to the surprise of Bartolomea, who did not however

at first perceive anything miraculous in the circumstance, but imagined that some of her family had been playing her a trick.

She therefore again removed it, and this time to keep it more securely she locked it up in a box. But her precautions proved vain,

for the first time she opened the box, she found the picture was no longer there, and hurrying to the oak tree, she was stupefied

with surprise and admiration on beholding the Madonna hanging in Her sylvan tabernacle as before. She no longer doubted of the

supernatural character both of this and the former removal, and persuaded that the Blessed Virgin had made choice of this tree for

Her residence, and that She did not choose Her picture to be venerated in any other place, she not only left it where it was,

but hastened to exhort her neighbors to visit the picture, before which she assured them she had received many graces.

A certain devotion toward the Madonna of the Oak had thus sprung up among the people of Viterbo, who were suffering

from many calamities—as well as from factions and civil wars with which Italy was at that time distracted, as from the assaults of

pestilence. In July of the year 1467, the misery of the people seemed at its height, the mortality was daily increasing,

when many of those who had been attacked by the pestilence were suddenly restored to health while praying before the

Madonna della Quercia.

On the 8th of the same

month, a citizen of Viterbo flying from the pursuit of some of the opposite faction who sought his life, was overtaken by them just

as he came up to

On the 8th of the same

month, a citizen of Viterbo flying from the pursuit of some of the opposite faction who sought his life, was overtaken by them just

as he came up to Our Lady's Oak,

and seeing no way of escape he raised his eyes to the picture and, invoking the aid of the

Blessed Virgin, was not disappointed in his confidence. His pursuers, who a moment before believed themselves sure of their prey,

suddenly lost sight of him; they sought him everywhere around and even in the tree—but in vain; and they were forced to retrace

their steps, disappointed and somewhat terrified by what seemed his supernatural disappearance. Meanwhile the citizens who had

beheld the discomfiture of his enemies, could only explain it by supposing, as was indeed the case, that Our Lady had rendered

him invisible to them, and entering Viterbo, he published his miraculous escape to all his neighbors. The affair was much talked of,

and the hermit explaining his former obscure hints, declared that the treasure he had so often spoken of was no other than Our Lady's

picture, and made known its miraculous removal both from his hermitage and the house of Bartolomea. The people of Viterbo determined

in consequence solemnly to invoke Our Lady's intercession against the pestilence, which before the end of July entirely ceased.

This almost instantaneous answer to their prayers filled them with devout gratitude, and crowds amounting to forty thousand persons

poured out of the city to return thanks to Our Lady before Her picture in the oak.

On the first Sunday in August an immense procession, including fourteen religious communities, visited this new

Sanctuary of the Madonna. The Bishop of Viterbo, at the head of all his clergy, secular and regular, and all the magistrates of

the city, came hither and celebrated Mass on a very simple wooden altar erected under the tree, and during this and the following

month similar scenes were constantly repeated. The fame of the Madonna della Quercia soon spread beyond Viterbo.

The hermit Pier Dominico constituted himself the Apostle of the new devotion, and on occasion of a terrible series of earthquakes

which about the same time threatened the ruin of the city of Siena, he exhorted the terrified people to make a vow to the

Madonna della Quercia, and recommend themselves to Her protection. The immediate cessation of this scourge proved the

reward of their faith, and as a token of gratitude, a deputation of Sienese citizens was dispatched to Viterbo,

bringing with them as their votive offering a silver tablet, on which was engraved a representation of the city.

I shall not pause here to enumerate the miracles wrought before the Holy Image. Their number and variety were

expressed by the votive offerings of all kinds suspended before the oak, among which were to be seen the chains of more than

one captive in Africa and Constantinople who attributed his deliverance from a Turkish dungeon to the intercession of Our Lady.

But the votaries of the Madonna often affirmed that the picture itself was in reality the greatest miracle. Exposed for fifty

years to every inclemency of weather under a tree, the branches of which formed its sole protection, its colors were fresh and

uninjured as on the first day it had been placed there. The majesty of Our Lady's countenance, and the life-like expression

with which the Holy Child appeared to be looking down on His worshipers, struck all who gazed on it. Moreover, as they said,

it excited different sentiments in the beholders, according to their different dispositions—it struck fear into the hearts of sinners,

kindled compunction in others, inspired the timid with hope, and the devout with fervor. And its miraculous powers were believed

to extend even to the oil burnt before the picture, and the wood of the tree on which it hung—several well-attested examples

of cures wrought by their use being on record.

The throng of pilgrims who constantly visited the Madonna rendered it necessary to take some steps for providing

priests to minister to their spiritual wants, and in 1467 a small chapel was erected for the celebration of Mass, the superiors of

the Dominican, Franciscan, Augustinian, and Servite convents being each severally requested to send one Father to hear the

confessions of the people. Even this was not found to be sufficient, and in the October of the same year the Bishop appointed

four parish priests to fulfill the same ministry, other officers, chosen from the nobles of Viterbo, being named to receive the

offerings of the pilgrims. At last he determined to establish some religious community on the spot, and a colony of the Gesuati,

recently founded by St. John Colombini, were chosen for the purpose. But as they found themselves unequal to the work,

which constantly increased, they resigned their post, and a council of the city authorities was called to determine who should

be their successors. The Dominican Fathers were thought by many the best suited for the charge, but as they already had one convent

in Viterbo, that of Sta. Maria in Gradi, there appeared an objection to founding two of the same Order in such close vicinity.

To settle the point, it was at last agreed to send the priors, or city magistrates, to the Porta Santa Lucia, on the road which

leads to Florence; they were to watch for the first religious coming into the city by that road, and they determined that the

Order to which he might happen to belong, whatever it were, should be selected as the guardians of the Madonna. Hardly had the

priors taken their post at the gate, when three friars appeared in sight, coming along the road from the direction of Florence.

They were Fr. Martial Auribelli, Master-General of the Dominicans, accompanied by his socii, returning from the visitation of the

northern provinces. When the priors had accosted the strangers and ascertained their dignity and character, they were filled with

a certain assurance that this was indeed the Order chosen by Our Lady, who appeared to have conducted hither the head of one of

the principal Orders dedicated in the Church to Her special honor, that Her will in the matter might be manifested beyond the

power of contradiction.

The care of the holy

image, and the missionary labors thereby entailed, were accordingly offered by the citizens of Viterbo to the Master-General of the

Friars Preachers, and by him willingly accepted; and a bull confirming this arrangement was obtained from Pope Paul II,

wherein faculties were granted for the erection of a church and convent. The foundations of the church were laid in the

July of 1470, and such was the ardor of those engaged in the work, and the zeal with which the people contributed the necessary means,

that the walls were roofed in by the following December; a fact considered sufficiently remarkable to be commemorated on a tablet

still preserved.

The care of the holy

image, and the missionary labors thereby entailed, were accordingly offered by the citizens of Viterbo to the Master-General of the

Friars Preachers, and by him willingly accepted; and a bull confirming this arrangement was obtained from Pope Paul II,

wherein faculties were granted for the erection of a church and convent. The foundations of the church were laid in the

July of 1470, and such was the ardor of those engaged in the work, and the zeal with which the people contributed the necessary means,

that the walls were roofed in by the following December; a fact considered sufficiently remarkable to be commemorated on a tablet

still preserved.

To the church was added a spacious cloister and monastery, a hospital (house of hospitality) for the reception

of pilgrims, and other buildings for the accommodation of the merchants and others, who assembled at the annual fairs held there

twice a year. Roads were opened and planted with avenues of trees, and considerable lands enclosed as vineyards and oliveyards.

Fountains and even aqueducts for the service of the friars and the public were constructed at vast expense, and the spot formerly

so wild and solitary was rapidly changed into a handsome and flourishing suburb.

The Roman Pontiffs have vied one with another in their testimonies of devotion towards the Madonna della Quercia,

and the privileges they have granted to this favored sanctuary. Pope Paul III was accustomed to visit it every year of his pontificate,

saying Mass at the Altar of Our Lady, and directed his statue should be place before the holy picture, where it may still be seen.

He even instituted a new order of knighthood under the particular protection of Our Lady, called the Order of the Lily,

the members of which wore a golden collar and medal, on one side of which appeared a representation of the Madonna della Quercia.

St. Pius V, himself a member of the Dominican Order, often visited the convent, and granted many indulgences to those who should pay

their devotions to the Madonna. When the fleet of the Christian allies was about to set sail for Lepanto, and extraordinary prayers

were being made to Our Lady for its success, St. Pius dispatched very special orders to the religious of La Quercia not to desist

from their appeals to their holy Patroness that She would obtain victory for the Christian forces. This was so well known at the

time that, after the victory of Lepanto, an immense number of the combatants visited La Quercia to hang up votive offerings of

thanksgiving, such as silver galleys and the like, wherein the Madonna della Quercia, who had been invoked by many of those engaged,

appears protecting Her votaries. The escape of one soldier, named Tomaso Roberti, had been specially remarkable. He had already

fallen severely wounded, and was being rapidly covered over with the bodies of the dead, when he caught the sound of his comrades'

voices shouting victory,

and, summoning his remaining strength, he invoked the aid of the Madonna della Quercia,

whereupon he felt his wounds staunched and anointed as it seemed by some unseen hand, and in a few moments found himself

perfectly restored; so that he was able to rise and free himself from the mass of corpses under which he lay buried.

He made a pilgrimage of gratitude to La Quercia, where he left a small statue of himself as a votive offering.

We might give a long list of the sovereign Pontiffs, Cardinals, and princes, whose names are to be found

enrolled among the pilgrims of La Quercia, and whose votive offerings, in the shape of silver tablets and statuettes,

enriched the church before it was plundered in the 16th century by the sacrilegious ruffians under the command of the

Constable de Bourbon. Or again we might speak of the great servants of God who refreshed their devotion before the altar of Mary,

such as the Blessed Colomba of Rieti, Blessed Lucy of Narni, and St. Hyacintha Marescotti, the latter of whom had a very special

love of the Madonna della Quercia, and being unable, as an cloistered religious woman, to visit Her sanctuary in person,

was wont very often to do so by deputy, and sometimes engaged a number of young children to visit the church barefoot

and receive Holy Communion there for her intention. Sometimes she obtained leave for some devout person to be shut up

in the holy chapel three days and three nights, in order to uninterruptedly implore for her divine grace and the powerful

intercession of the Madonna.

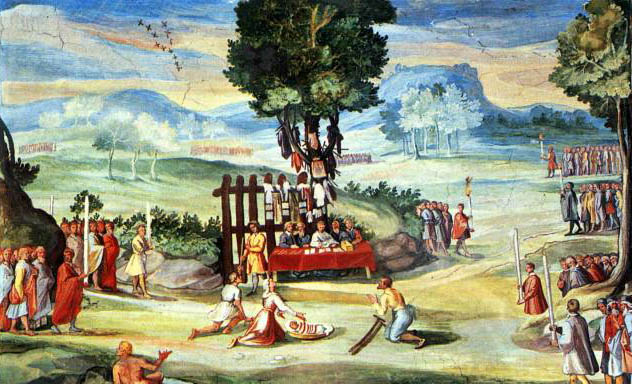

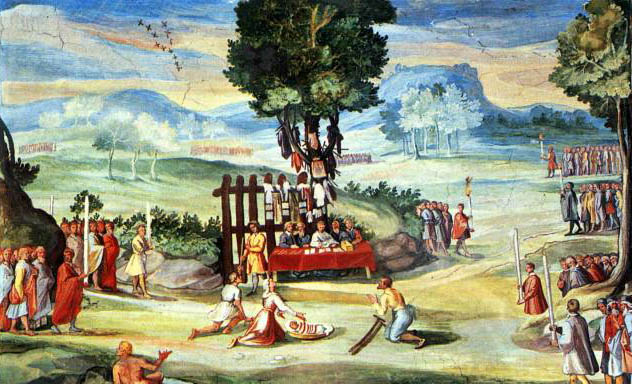

The history of the

graces and miracles obtained at this sanctuary fill an entire volume. The circumstances of many of them are painted on the walls

of the cloisters or represented in tablets, statues, and other offerings. These graces are of every variety,

including miraculous cures, deliverances from wild beasts, fire, tempests, and earthquakes, restoration of the deaf and dumb,

and escapes from Turkish slavery. Thus, a certain knight of Viterbo, named Papirio Buffi, being taken prisoner by the Moors,

and kept in slavery in Africa, made his vows to Our Lady della Quercia, and soon after found means of escaping in a little skiff,

which, altogether unsuited as it was for such a voyage, brought him safely to Civita Vecchia, in a wonderfully short space of time.

To manifest his gratitude for this deliverance, and his firm faith that he was indebted for it to Our Lady, Papirio set out at once

for La Quercia, wearing the same clothes in which he had landed, namely, the linen shirt and trousers of an African slave,

and afterwards as his thank-offering erected the marble chapel in which we see painted the appropriate subject of the escape of

St. Raymond Pennafort.

The history of the

graces and miracles obtained at this sanctuary fill an entire volume. The circumstances of many of them are painted on the walls

of the cloisters or represented in tablets, statues, and other offerings. These graces are of every variety,

including miraculous cures, deliverances from wild beasts, fire, tempests, and earthquakes, restoration of the deaf and dumb,

and escapes from Turkish slavery. Thus, a certain knight of Viterbo, named Papirio Buffi, being taken prisoner by the Moors,

and kept in slavery in Africa, made his vows to Our Lady della Quercia, and soon after found means of escaping in a little skiff,

which, altogether unsuited as it was for such a voyage, brought him safely to Civita Vecchia, in a wonderfully short space of time.

To manifest his gratitude for this deliverance, and his firm faith that he was indebted for it to Our Lady, Papirio set out at once

for La Quercia, wearing the same clothes in which he had landed, namely, the linen shirt and trousers of an African slave,

and afterwards as his thank-offering erected the marble chapel in which we see painted the appropriate subject of the escape of

St. Raymond Pennafort.

Another class of miracles includes those who have invoked Our Lady’s intercession when condemned to death,

and whose subsequent release has been attributed to Her intercession. I will give but one example of these, which rests

upon the evidence of a multitude of eye-witnesses. In the year 1503 a certain citizen of Modena, named Fabrizio Padovani,

was accused of theft, and being put to the torture, confessed the crime through extremity of pain, although he was, in fact,

entirely innocent. He was accordingly condemned to death, but the confessor who assisted in preparing him for execution felt

satisfied of his innocence, and urged him to have recourse to Our Lady della Quercia, with full confidence in the power of

Her intercession. When the last hour came Fabrizio addressed the assembled crowd from the scaffold, and declared his innocence

of the crime for which he was to suffer, and at the same time asked them as a last charity to join with him in saying a Pater

and Ave in honor of the Madonna della Quercia, that She might at least assist him in his last agony. The spectators knelt down,

and all repeated the prayer with him aloud; then the executioner fastened the rope around his neck and threw him off the ladder.

But at that moment the rope and gallows broke, bringing to the ground both the executioner and the condemned. The gallows were

set up a second time and firmly secured, but the same accident occurred again, whereupon the people raised a cry of A miracle!

A miracle!

But this excitement did not prevent the executioner from taking measures for hanging his unfortunate

prisoner a third time. Whilst he stood with the broken rope around his neck, some workmen leisurely set up the gallows,

and fastened it with blocks and iron clamps, and once more Fabrizio was called on to ascend the ladder. But when the

executioner was in the act of throwing him off, the gallows again gave way. Everyone standing on the scaffold was thrown down,

and the machinery was broken into several pieces. The magistrates who were present were so impressed by the extraordinary

recurrence of this accident that, yielding to the clamorous cries of the spectators, they remanded Fabrizio back to prison,

and caused a fresh inquiry to be made into his case, which resulted in completely proving his innocence. On regaining his

freedom his first act was to present an ex-voto offering to the Madonna della Quercia.

The appearance of the picture remained altogether unchanged over the centuries. It stands over the high altar

of the church, where the visitor may also see the trunk of the oak to which it was formerly attached. Pilgrims have continued

to flock to it, as in the 15th century, and some time back the devotion of the Roman people to this sanctuary caused the

old church of San Niccolò, in the Piazza Farnese, in Rome, to be restored and rededicated to the Madonna della Quercia,

a copy of the original picture being deposited there, fastened upon a silver oak branch.

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

At a short distance from the walls of Viterbo, on a spot formerly known as the Campo Grazzano, stands the celebrated Convent of

La Quercia, with its beautiful campanile, rising above the trees which line the road leading to the Porta Santa Lucia.

The church with its adjacent cloister, designed by Bramante, is considered a masterpiece by that artist, and its situation

would seem as if chosen in order to command the most magnificent view. The woody heights of Mount Cimino rise on the south;

on the north appear the town and hills of Montefiascone; the Appenines are on the east; whilst in the opposite direction you

look over a richly variegated country towards the distant Mediterranean. However the site of the convent was not fixed in

consequence of its picturesque beauty; it was determined by what may be called accidental circumstances, unless our readers

are willing to believe that, as is affirmed of so many other sanctuaries of Our Lady, She Herself made choice of the spot whence

She had determined to dispense Her graces.

At a short distance from the walls of Viterbo, on a spot formerly known as the Campo Grazzano, stands the celebrated Convent of

La Quercia, with its beautiful campanile, rising above the trees which line the road leading to the Porta Santa Lucia.

The church with its adjacent cloister, designed by Bramante, is considered a masterpiece by that artist, and its situation

would seem as if chosen in order to command the most magnificent view. The woody heights of Mount Cimino rise on the south;

on the north appear the town and hills of Montefiascone; the Appenines are on the east; whilst in the opposite direction you

look over a richly variegated country towards the distant Mediterranean. However the site of the convent was not fixed in

consequence of its picturesque beauty; it was determined by what may be called accidental circumstances, unless our readers

are willing to believe that, as is affirmed of so many other sanctuaries of Our Lady, She Herself made choice of the spot whence

She had determined to dispense Her graces. On the 8th of the same

month, a citizen of Viterbo flying from the pursuit of some of the opposite faction who sought his life, was overtaken by them just

as he came up to

On the 8th of the same

month, a citizen of Viterbo flying from the pursuit of some of the opposite faction who sought his life, was overtaken by them just

as he came up to  The care of the holy

image, and the missionary labors thereby entailed, were accordingly offered by the citizens of Viterbo to the Master-General of the

Friars Preachers, and by him willingly accepted; and a bull confirming this arrangement was obtained from Pope Paul II,

wherein faculties were granted for the erection of a church and convent. The foundations of the church were laid in the

July of 1470, and such was the ardor of those engaged in the work, and the zeal with which the people contributed the necessary means,

that the walls were roofed in by the following December; a fact considered sufficiently remarkable to be commemorated on a tablet

still preserved.

The care of the holy

image, and the missionary labors thereby entailed, were accordingly offered by the citizens of Viterbo to the Master-General of the

Friars Preachers, and by him willingly accepted; and a bull confirming this arrangement was obtained from Pope Paul II,

wherein faculties were granted for the erection of a church and convent. The foundations of the church were laid in the

July of 1470, and such was the ardor of those engaged in the work, and the zeal with which the people contributed the necessary means,

that the walls were roofed in by the following December; a fact considered sufficiently remarkable to be commemorated on a tablet

still preserved. The history of the

graces and miracles obtained at this sanctuary fill an entire volume. The circumstances of many of them are painted on the walls

of the cloisters or represented in tablets, statues, and other offerings. These graces are of every variety,

including miraculous cures, deliverances from wild beasts, fire, tempests, and earthquakes, restoration of the deaf and dumb,

and escapes from Turkish slavery. Thus, a certain knight of Viterbo, named Papirio Buffi, being taken prisoner by the Moors,

and kept in slavery in Africa, made his vows to Our Lady della Quercia, and soon after found means of escaping in a little skiff,

which, altogether unsuited as it was for such a voyage, brought him safely to Civita Vecchia, in a wonderfully short space of time.

To manifest his gratitude for this deliverance, and his firm faith that he was indebted for it to Our Lady, Papirio set out at once

for La Quercia, wearing the same clothes in which he had landed, namely, the linen shirt and trousers of an African slave,

and afterwards as his thank-offering erected the marble chapel in which we see painted the appropriate subject of the escape of

St. Raymond Pennafort.

The history of the

graces and miracles obtained at this sanctuary fill an entire volume. The circumstances of many of them are painted on the walls

of the cloisters or represented in tablets, statues, and other offerings. These graces are of every variety,

including miraculous cures, deliverances from wild beasts, fire, tempests, and earthquakes, restoration of the deaf and dumb,

and escapes from Turkish slavery. Thus, a certain knight of Viterbo, named Papirio Buffi, being taken prisoner by the Moors,

and kept in slavery in Africa, made his vows to Our Lady della Quercia, and soon after found means of escaping in a little skiff,

which, altogether unsuited as it was for such a voyage, brought him safely to Civita Vecchia, in a wonderfully short space of time.

To manifest his gratitude for this deliverance, and his firm faith that he was indebted for it to Our Lady, Papirio set out at once

for La Quercia, wearing the same clothes in which he had landed, namely, the linen shirt and trousers of an African slave,

and afterwards as his thank-offering erected the marble chapel in which we see painted the appropriate subject of the escape of

St. Raymond Pennafort.