The North American Martyrs (†1642-9; Feast – September 26)

Part II – Era of Martyrdom Begins

By 1642 the Huron mission was practically reduced to destitution. The Fathers were in need of medicines, clothing, vestments,

and altar necessities. Even food was scarce, due to a lack of rain and a poor harvest. An expedition would have to be sent to

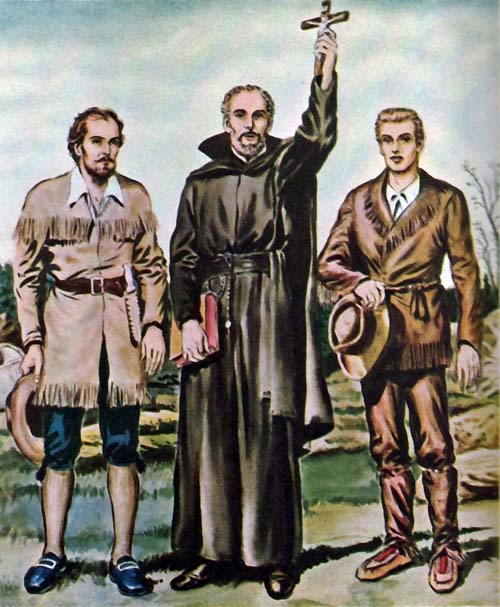

Quebec to obtain the necessary supplies. Father Isaac Jogues was chosen to lead the company of five Frenchmen and eighteen Hurons

on this dangerous journey. The excursion was especially perilous because of the increasing number of Iroquois war parties

which had been recently encountered along the Saint Lawrence River. The little convoy departed in June and, in spite of the hazards,

safely arrived at Quebec a month later.

By 1642 the Huron mission was practically reduced to destitution. The Fathers were in need of medicines, clothing, vestments,

and altar necessities. Even food was scarce, due to a lack of rain and a poor harvest. An expedition would have to be sent to

Quebec to obtain the necessary supplies. Father Isaac Jogues was chosen to lead the company of five Frenchmen and eighteen Hurons

on this dangerous journey. The excursion was especially perilous because of the increasing number of Iroquois war parties

which had been recently encountered along the Saint Lawrence River. The little convoy departed in June and, in spite of the hazards,

safely arrived at Quebec a month later.

It was early August when the heavily packed canoes were finally ready to be navigated back to Sainte Marie.

The returning party was comprised of about thirty-five Hurons, under the leadership of the Christian Chief Eustace Ahatsistari,

as well as Father Jogues, several French workmen, and a donné named RENÉ GOUPIL. Goupil was only a year younger than

Father Jogues, thirty-four at this time. He had been received into the Jesuit novitiate in his youth, but was forced to leave

the Order because of illness. Upon recovering his health, Goupil offered his services as a donné and had been serving

the mission in Quebec for the past two years. His assistance was now desired in Huronia,

for he was a good nurse and a skillful surgeon.

The first day of the return trip passed safely, but on the second day war whoops and musket fire suddenly split the air.

The Iroquois sprang up from the cover of the tall grass, bombarding the flotilla with lead balls and arrows. The Hurons shouted back

cries of defiance. The brave who piloted Father Jogues' canoe crashed it against the shore and the priest was catapulted into a

thicket of high weeds, wherein he discovered he could conceal himself from the sight of the enemy.

Meanwhile, other canoes had hit the shore. In the open field stretching out before him Father Jogues could see

Eustace and René, plus a handful of Huron braves preparing to do battle hand-to-hand against twice as many Mohawks.

(The Mohawks were one of the tribes of the Iroquois nation.) Suddenly shouts from the shore announced the arrival

of about seven enemy canoes from which leaped forty more whooping savages. The Hurons fought valiantly but the number of the

enemy was overpowering.

Father Jogues still had not been detected. He could easily escape if he dashed for the woods. But, how could he flee?

His friend René was a captive; he might be tortured and killed. Not only René, but so many Christian and unbaptized Hurons

who had been taken would need his priestly help. No, his people needed him; there were souls to be saved. Jumping up from

his hiding place, Father Jogues waved his arms high in the air and shouted words of surrender. He was then apprehended and

beaten by a Mohawk brave and soon found himself with the other prisoners. Falling upon the neck of Goupil, Father Jogues assured him,

with tears, that this tragedy would be for the glory of God.

Mohawk Prisoner

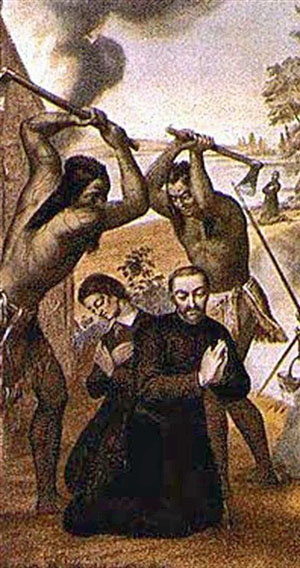

Not many days after, the hungry and aching captives were exultantly displayed to a band of two hundred or so Mohawk braves,

who met the returning war party on an island in Lake Champlain (northeastern New York). When the canoes landed, the howling

barbarians danced about in sheer frenzy, slashing the prisoners with their knives and tearing at their flesh with their long

fingernails. Then, picking up knotted clubs and thorn-studded rods, they formed two parallel lines up the slope of the hill

ascending from the beach.

Not many days after, the hungry and aching captives were exultantly displayed to a band of two hundred or so Mohawk braves,

who met the returning war party on an island in Lake Champlain (northeastern New York). When the canoes landed, the howling

barbarians danced about in sheer frenzy, slashing the prisoners with their knives and tearing at their flesh with their long

fingernails. Then, picking up knotted clubs and thorn-studded rods, they formed two parallel lines up the slope of the hill

ascending from the beach.

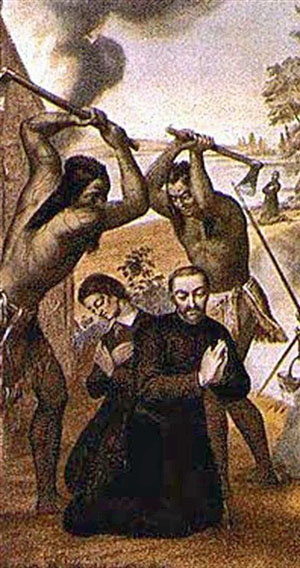

One by one the captives were forced to run between the columns of club-swinging brutes who took delight in nearly

pounding their victims to death. This was the traditional Indian "welcoming committee" for prisoners of war. It was known as

"running the gauntlet." Father Jogues was put last in line. He was a special guest; for him was reserved the worst punishment.

With head bent low he darted wildly through the mass of swinging cudgels. Blows fell hard and painful on his head, neck, back,

and arms, while his sides ached from the sting of the thorny rods being slapped into his flesh and tearing it to pieces.

He stumbled to the ground stunned, and they had to drag his unconscious body the rest of the way up the hill.

When he regained his senses, some of the tormentors burnt his arms and legs with a torch; others dug their fingernails

into his wounds. Someone then took his thumb and crunched it between his teeth with such ferocity that he tore the skin to shreds,

exposing the crushed bone. The failing priest was so weak that he could scarcely stand. His fellow prisoners, twenty-one in all,

had likewise been so mercilessly tortured, that many of them were half dead. But the captives could not be killed;

for they had not as yet been triumphantly paraded before the entire Iroquois nation.

With little rest and no food, they were hastened along the trail to the land of the Mohawks. While enduring such

torments, Father Jogues was not altogether bereft of consolation, for along the way he was able to baptize some of his pagan Huron

companions.

René Goupil, at this time, expressed his desire to extend his promises as a donné to the perpetual vows of a religious.

His profession was joyfully received and blessed by Father Jogues, who marveled at René's constancy and holiness.

When Father Jogues suggested that René attempt to escape, his counsel was in vain. Goupil replied pleadingly, Allow me to die with

you, Father, for I cannot desert you.

The Tortures Continued

After eighteen days the agonizing procession at last reached the Mohawk village of Ossernenon

(Auriesville, New York). Again the prisoners were subjected to the knives of vicious braves and the nails of seething squaws,

who sliced and dug at their festering wounds. Father Jogues was considered the most detestable of them all.

He was a Blackrobe, and their Dutch neighbors had warned them to beware of those French priests. They were "sorcerers."

The Protestant Hollanders warned them particularly about a certain sign these men often made with their right hands...

a certain movement that resembled the shape of a cross. The bloodthirsty villagers vied with one another in crunching

Father Jogues' fingers in their mouths, macerating them pitiably, and tearing out the only two fingernails that remained to him.

Again the two familiar lines were formed and the prisoners were forced to run the gauntlet.

Father Jogues watched in horror as poor René ran clumsily into the cruel pathway standing straight up and

leaving his head pitifully unprotected. Goupil fell senseless to the ground, his face drenched in blood from

the thudding blows that met him full force. Father Jogues, who knew better how to protect himself, tore through

the fray with his head bent low between his arms, but in the end his bald head was a mass of bloody welts.

Atop the summit of the hill the poor victims were burned and lacerated one by one. A Christian Algonquin woman

was compelled to saw off Father Jogues' left thumb with an oyster shell. Even at night they were not left alone.

While the professional torturers snored away, the little children approached and dropped burning sticks and hot coals

on their bare bodies, stretched out on the ground and bound by stakes.

The captives were next marched to the neighboring village of Andagaron (Randall, New York);

then on to Tionontoguen (Sprakers, New York), and tortured in much the same manner.

Not long after, a council was held to determine the fate of the prisoners. The Huron braves, of course, were to be

tortured and killed. However, the chiefs decided to spare the white men, intending to return with them as hostages to Quebec.

The Mohawk chieftains knew how much the French reverenced their Blackrobes. Ondessonk and the others would provide considerable

bargaining power.

In a bitter agony of soul Father Jogues stood by and watched the horrible slaughter of his Huron children.

Many had been exemplary Christians for a number of years; some were just recently baptized. He had begotten them all in Christ.

In a bitter agony of soul Father Jogues stood by and watched the horrible slaughter of his Huron children.

Many had been exemplary Christians for a number of years; some were just recently baptized. He had begotten them all in Christ.

...While each one suffered but his own pain,

Father Jogues wrote later, I suffered that of all. I was afflicted with

a great anguish, great as one may believe the heart of a most loving parent is afflicted when he has to witness the sufferings

of his children.

Eustace Ahatsistari was sentenced to die in another village. Those who witnessed the end said that all

the while he was being tormented he prayed aloud for his persecutors. Several blows from a hatchet severed his head,

thus sending to God a most noble and valiant soldier of Christ.

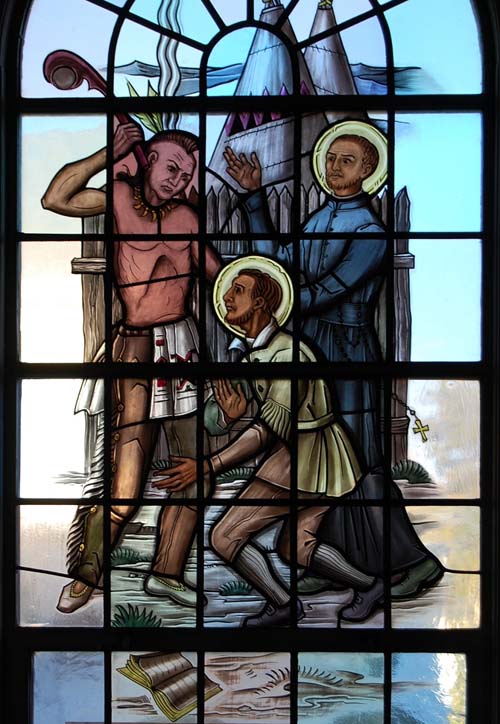

The First Martyr

It was nothing short of a miracle that Father Jogues and René Goupil ever recovered from their wounds,

but in a few weeks, though scarred and maimed, they were once more on their feet and somewhat stronger. Though free to move

about the village and visit the longhouses, the two Jesuits had to avoid any action that would irritate their captors.

To Father Jogues such carefulness was second nature, but Goupil was too open in his devotions. He was once seen by a

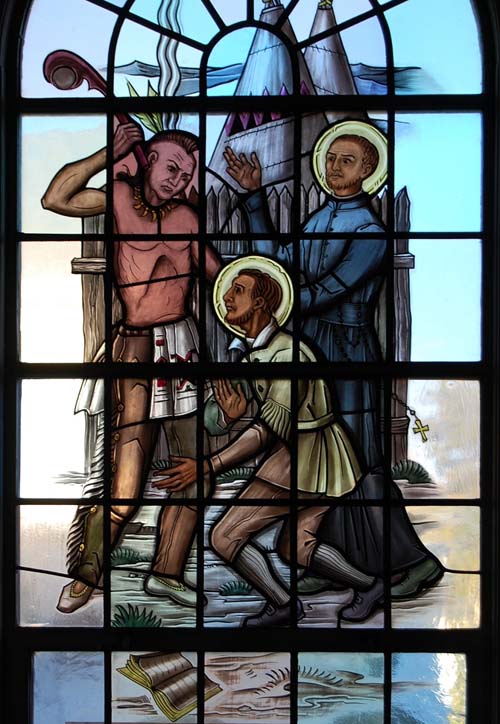

superstitious old warrior making the Sign of the Cross over the old man's grandson. One evening Father Jogues and René

went outside the palisades of the village to pray the Rosary. As they were returning, two braves suddenly drew near and

gruffly ordered them to go back to the village.

Walk ahead,

growled one of the tall warriors as he motioned with his finger to Ondessonk.

Father Jogues took a few steps and turned around. He saw the Iroquois draw out a tomahawk from beneath this blanket.

Instantly the savage swung it high in the air and brought it down with a crash into the head of Goupil.

René staggered a step and calling out, Jesus, Jesus, Jesus!

he fell to the ground. Two more vicious blows

from a crimsoned hatchet extinguished the last breath of life in René Goupil. It was the 29th day of September,

the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel, when this heroic young man went to his eternal reward. Truly, he died a martyr—a martyr

for the Cross of Christ—for it was precisely because he was so eager to display the sacred sign of our Redemption

that his life was taken. Father Jogues knelt beside the body of his friend and pronounced the words of absolution.

He felt certain that René was already in Paradise.

The next morning the fearless priest strode out of the village in search of the body of his martyred brother,

despite numerous threats that he himself would be killed if he ventured a foot outside of the palisades. With the help of

an Algonquin slave he found what was left of René's body dumped in the grass of a ravine. He reverently picked up the holy

remains and buried them underneath some stones in a stream, intending soon to return and give them a more decent burial.

But upon revisiting the spot he could not find the blessed body of René and soon learned that young Iroquois

braves had taken the body and dragged it to the forest nearby. In the spring, Father Jogues found René's fractured skull

and some of his bones. These he reverently kissed and buried beneath the trunk of a tree.

But upon revisiting the spot he could not find the blessed body of René and soon learned that young Iroquois

braves had taken the body and dragged it to the forest nearby. In the spring, Father Jogues found René's fractured skull

and some of his bones. These he reverently kissed and buried beneath the trunk of a tree.

Father Jogues Escapes

As Ondessonk was being dragged from one village to another during his long and weary enslavement,

he conducted himself exactly as he had done among the Hurons. Every day he would enter the longhouses in search of the sick

that he might win them to the Faith before they died. True, he had to perform his apostolic labors cautiously,

but before long he had managed, under God's protection, to baptize seventy dying Mohawks. This afforded him great consolation.

In all Father Isaac Jogues endured thirteen months of this tenuous ambassadorship. A source of wonder to the

"Reformed" Church Dutchmen who settled at Fort Orange (Albany, New York) not far away, the Blackrobe often tried to explain

to their disbelieving ears that he sought nothing for himself among the Indians. To their offers to aid him in escaping he

simply said, No.

He had been sent to them by God to preach the gospel, the very gospel which was being abandoned by

so many millions in Europe who had left the Apostolic Faith of their ancestors to embrace the libertine creed of Luther or

the fatalistic view of Calvin.

However, conditions were changing. An Iroquois war party returned to Ossernenon after suffering another

humiliating defeat from the French. Providentially Father Jogues was away on a fishing expedition at the time,

or he would have been killed instantly. When the expedition stopped to trade at the Dutch settlement of Rensselaerswyck,

he learned there about the French victory. Father Jogues also found out that sentence had been passed against him at

Ossernenon and that as soon as he returned he would be tortured and killed. Father Isaac was not afraid to die,

in fact he longed for martyrdom. However, he began to prayerfully reconsider the pleas of the Hollanders that he escape.

What purpose would his death serve at this time? The Christian Hurons were either dead or scattered far and wide as slaves

of Iroquois families. These Hurons were protected now by Indian law; no one but their masters could kill them.

René was dead. Surely if he broke away, he could return to the Iroquois at a later date to convert them when conditions

were more favorable. Father Jogues concluded that the will of God lay in this course... only he must be quick about it,

for he was running out of time!

One August night he slowly got up from between two snoring guards, tip-toed out the door of the barn wherein

they were sleeping, and ran like a deer for freedom. During this escape Father Jogues was bitten on the leg by a ferocious mastiff,

and while the tortures of the Mohawks had not killed this holy man, the vicious dog bite nearly did.

Due to improper medical treatment, in a few weeks the priest's entire leg would swell alarmingly and gangrene would set in.

A skilled surgeon finally saved Father Jogues' life and his leg by performing, just in the nick of time, a most painful operation.

When the Mohawks discovered that their prisoner was gone, they flew into a rage. They threatened the Dutch

that they would burn down their homes and slaughter everyone in them if Ondessonk were not returned.

Throughout the crisis Jogues lay concealed in a stuffy attic of an old storekeeper's shop. The settlers were extremely

afraid of what the Mohawks might do, but thanks to the courage of their commandant, Arendt Van Corlaer,

the French Jesuit was not given back to the enraged savages. Eventually the furor of the Indians subsided

after they had been many weeks searching about the settlement with no success. It was a sheer miracle that

Father Jogues was never discovered.

Hearing of the plight of the Jesuit priest, the Governor of New Amsterdam (New York City), William Kieft,

ordered Van Corlaer to send the refugee down to him immediately. This being done, the kind-hearted Governor made

arrangements for Father Jogues' passage back to Europe. Aboard a tiny vessel, Father Jogues went forth across the Atlantic.

He could hardly believe that after seven years among the Indians he was on his way home to France.

It was Christmas Day, 1643, when the poorly clad missionary again set foot on his native soil.

The inhabitants of the little fishing village in lower Brittany, where he landed, showed him great hospitality.

With the assistance of a kind merchant who offered Father Jogues a horse, the blessed Jesuit was soon on the road to Rennes,

where the college of the Society of Jesus was located. Before sunrise on January 5th, he knocked at the door of the college,

knowing it to be the hour for the community Mass. He was still dressed in peasant's garb, with a sorry hat perched atop his

scarred head. The porter eyed him suspiciously. Father Jogues merely identified himself as a "poor man" from Canada and

asked if he might please speak to the rector. Father Rector had been vesting for Mass. However, he was anxious to

receive news from the Fathers in Canada, and fearing that the man might leave if he were asked to wait, he took off

his alb and came to the door. He invited the "poor man" into the parlor. It was still dark and they spoke by the light of a candle.

Is it true that you have come from Canada?

the Rector asked.

Yes,

the unseemly visitor answered.

Do you know Father de Brébeuf?

Extremely well

he said.

And Father Isaac Jogues, did you know Father Isaac Jogues?

I knew him very well indeed,

replied the stranger.

Is he still alive?

questioned the Rector, his voice stiffening. Have not those barbarians murdered him?

He is at liberty,

the poor man assured him with a hesitant gasp. Reverend Father,

Jogues burst into tears,

it is he who speaks to you.

Soon all of France was talking about this missionary priest, a prisoner of savages. His story was the daily

topic of conversation. People vied with one another to meet him, to ask him questions, to receive his blessing,

to kiss his mangled hands. The Queen Regent herself, Anne of Austria, received him as an honorary guest, and with tears in

her eyes, asked him to relate what he had suffered. Then she examined with devotion his mutilated fingers.

Father Jogues was granted special permission by Pope Urban VIII to say Mass, despite his missing fingers. The Pontiff stated,

It is unbefitting that a martyr of Christ should not drink the Blood of Christ.

Such publicity was too much, however, for the genuine humility of the holy apostle. He longed to be back among the Indians.

The children of the North American forests had staked a claim on his heart and he could not rest until he had won them all for Christ.

Consequently after only a three-month stay in his own country, he was allowed to embark for New France once more.

I go, but I shall never come back again,

were his words on the eve of his departure. In June 1644, he stepped ashore at

Quebec and received a tumultuous welcome from his thoroughly astonished and overjoyed fellow Jesuits.

Distress in New France

Father Jogues quickly learned the sad state of affairs to which the missions in New France had declined.

In August 1644, the Jesuits sought to slip through the enemy-infested waterways and trails with the needed supplies for

Mission Sainte Marie in Huronia. Father Jean de Brébeuf volunteered to head this risky expedition.

Since his return from the Hurons, Echon had been given charge of the Christian Indian settlement at Sillery, near Quebec.

All the while, this pioneer of the Huron mission was anticipating the day when he could labor again among the Wyandot people,

and at last the opportunity had arisen. A virtuous thirty-one year old Jesuit, FATHER NOEL CHABANEL,

would accompany Father Brébeuf on this his third and final journey to the Hurons. Father Chabanel had arrived in

New France the previous year. He found it very difficult to learn even a little of the Indian languages,

and thought it impossible to become accustomed to the crude Indian life and manner. Yet he did his best

to conceal these repugnances, and privately vowed to remain the rest of his life among the savages of New France,

a vow he would one day seal with his blood.

In some villages there were now more Christians than heathens, for gradually Huronia was becoming a Christian nation.

If granted a period of peace, it seemed the entire Huron people might have accepted the Faith. But it is reserved only for the secret

and adorable judgments of God to know why the war-torn Hurons were denied this desired tranquility. The Iroquois' bloody campaign

to conquer the Hurons continued. With more frequent and forceful raids they not only attacked Huron convoys and hunting parties,

but even boldly advanced into Huron country plundering several villages there. The intrepid Jesuits, renewed with a greater

zeal upon Echon's return to Huronia, remained at their stations, exhorting and teaching the Indians regardless of the

impending dangers.

Mission of Peace

The summer of 1645, however, kindled a spark of hope for the despairing Hurons. Not all was shining brightly for the

Iroquois nation. Endless war was sapping the strength of the tribes, as even their victories were costly in manpower.

The summer of 1645, however, kindled a spark of hope for the despairing Hurons. Not all was shining brightly for the

Iroquois nation. Endless war was sapping the strength of the tribes, as even their victories were costly in manpower.

A mission of goodwill to Mohawk country would strengthen the existing agreements and might even induce

the other Iroquois tribes to enter into the negotiations. Father Jogues, who had been praying to be sent back to the

place of his former captivity, with the approval of the Jesuit superiors, was selected by the Governor to carry out

this important assignment. In view of its dangerous circumstances the venture was placed under the patronage of

all the Holy Martyrs.

On the 16th of May, 1646, Father Jogues, in civilian garb, a French layman, two Algonquins and four

Mohawk guides set out on the journey. They arrived in the early part of June, causing much excitement in the Mohawk villages.

A great multitude gathered together to see the ambassadors, and those who had once made life so miserable for Ondessonk,

now pretending to have forgotten the past, greeted him cordially. Memories crowded Father Jogues' mind:

the excruciating pain of the gauntlet, the agony of the torture platform... and the death of René Goupil.

As soon as the opportunity presented itself, he visited the ravine to venerate René's sacred remains.

A general assembly of the sachems, or chiefs, was held to greet the ambassadors. Speeches of benevolence

were delivered, and belts of wampum and furs exchanged. The council ended favorably and before his departure

Father Jogues administered the Sacraments to the Christian captives, and baptized many savages who were dying.

Having completed the mission of diplomacy, Father Jogues and his companions then made the long journey

back to Quebec, arriving on the third of July.

Martyrdom of Father Isaac Jogues and Jean de Lalande

After two months, in August 1646, the Hurons began gradually to appear in increasing numbers at Trois-Rivières.

In September they held a council with Governor Montmagny, who expressed his desire that they also send emissaries of peace

to the Mohawks. The Hurons agreed to the proposal and asked if Father Jogues could accompany them.

Father Jogues was soon notified of the Huron request and met with his Superior and the Governor at Trois-Rivières.

The zealous Jesuit was overjoyed and profoundly grateful that God had so quickly answered his prayers.

Without hesitation he voiced his desire to revisit the Mohawks, only this time not merely as a French delegate in

civilian dress, but as a Catholic missionary in his religious cassock. Despite the obvious danger involved,

he received both the Governor's unqualified permission and his Superior's paternal blessing for the undertaking.

On September 24, 1646, the pious priest, accompanied by the young donné, JEAN DE LALANDE,

and several Hurons, embarked on the journey. Eventually, all except for one of the Hurons abandoned the perilous venture.

They had nearly reached Ossernenon, in mid-October, when the anticipated hazards became realities.

A Mohawk war party, on its way to attack the French, captured Father Jogues' little company of three.

They were stripped of clothing, brutally beaten with fists and clubs and hurried along the trail to the Iroquois village.

The peace had been reneged by the Mohawk Bear Clan.

On September 24, 1646, the pious priest, accompanied by the young donné, JEAN DE LALANDE,

and several Hurons, embarked on the journey. Eventually, all except for one of the Hurons abandoned the perilous venture.

They had nearly reached Ossernenon, in mid-October, when the anticipated hazards became realities.

A Mohawk war party, on its way to attack the French, captured Father Jogues' little company of three.

They were stripped of clothing, brutally beaten with fists and clubs and hurried along the trail to the Iroquois village.

The peace had been reneged by the Mohawk Bear Clan.

But why had the savages become so violent and blood-thirsty? He found that the Iroquois were obsessed with

the idea that he was an evil sorcerer, and that the black box which he had left, containing his vestments and religious articles,

had cast a curse on them. For shortly after Father Jogues' departure in June, a contagious disease had killed many in their

villages and, in addition to this, a swarm of worms had destroyed almost their entire harvest. The Iroquois medicine men

had thrown Ondessonk's black box, unopened, into the river. They then stirred up bitter hatred against the paleface who,

they alleged, was seeking revenge on the Iroquois for having tortured him.

In the almost deserted village of Ossernenon, meanwhile, a small violent group of the Bear Clan secretly plotted

to kill the captives before any decision could be reached by the council. They cunningly sought out Ondessonk and invited him

to enjoy a meal at their lodge. To refuse an invitation was a grievous offense. He placed his confidence totally in

Divine Providence, and courageously proceeded to the Bear Clan cabin. As he lifted the door flap and stooped to enter

the lodge, an assailant within raised his hatchet. An Iroquois who had accompanied Father Jogues tried to ward off the

assault, but a fierce blow sliced the protector's arm and struck the head of the saintly priest, felling him to the ground.

In an instant the martyrdom of Father Isaac Jogues had been completed. The group of murderers immediately cut off his head

and stuck it on one of the palisade posts of the village. His venerable body was then thrown into the Mohawk River.

From the exultant cries of the warriors, Jean de Lalande suspected what had happened.

Shortly, word was brought to the Wolf Clan cabin where Jean had remained… Father Jogues was dead.

The young donné prayed for the strength he needed to likewise suffer whatever God willed him to endure.

He longed to search for the blessed Martyr's body before it was completely mutilated or lost,

but while in the company of his sympathetic Iroquois guards, this was for the moment impossible.

When the evening's clamor had subsided and all in his lodge were asleep, Jean silently made his way out

the door to find his beloved Father Isaac. But his first step from the cabin was his last step toward eternity.

An awaiting savage of the Bear Clan split his head with a mighty stroke of his tomahawk.

His head was cut off and placed on the palisade next to Father Jogues' and his body was also thrown into the river.

News of the martyrdoms did not reach Quebec until some eight months later, in June of 1647.

While the Fathers received the reports with sorrow, they also had reason to be thankful,

for they now had two more advocates praying for them in Heaven. (To be continued...)

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Back to Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

By 1642 the Huron mission was practically reduced to destitution. The Fathers were in need of medicines, clothing, vestments,

and altar necessities. Even food was scarce, due to a lack of rain and a poor harvest. An expedition would have to be sent to

Quebec to obtain the necessary supplies. Father Isaac Jogues was chosen to lead the company of five Frenchmen and eighteen Hurons

on this dangerous journey. The excursion was especially perilous because of the increasing number of Iroquois war parties

which had been recently encountered along the Saint Lawrence River. The little convoy departed in June and, in spite of the hazards,

safely arrived at Quebec a month later.

By 1642 the Huron mission was practically reduced to destitution. The Fathers were in need of medicines, clothing, vestments,

and altar necessities. Even food was scarce, due to a lack of rain and a poor harvest. An expedition would have to be sent to

Quebec to obtain the necessary supplies. Father Isaac Jogues was chosen to lead the company of five Frenchmen and eighteen Hurons

on this dangerous journey. The excursion was especially perilous because of the increasing number of Iroquois war parties

which had been recently encountered along the Saint Lawrence River. The little convoy departed in June and, in spite of the hazards,

safely arrived at Quebec a month later. Not many days after, the hungry and aching captives were exultantly displayed to a band of two hundred or so Mohawk braves,

who met the returning war party on an island in Lake Champlain (northeastern New York). When the canoes landed, the howling

barbarians danced about in sheer frenzy, slashing the prisoners with their knives and tearing at their flesh with their long

fingernails. Then, picking up knotted clubs and thorn-studded rods, they formed two parallel lines up the slope of the hill

ascending from the beach.

Not many days after, the hungry and aching captives were exultantly displayed to a band of two hundred or so Mohawk braves,

who met the returning war party on an island in Lake Champlain (northeastern New York). When the canoes landed, the howling

barbarians danced about in sheer frenzy, slashing the prisoners with their knives and tearing at their flesh with their long

fingernails. Then, picking up knotted clubs and thorn-studded rods, they formed two parallel lines up the slope of the hill

ascending from the beach. In a bitter agony of soul Father Jogues stood by and watched the horrible slaughter of his Huron children.

Many had been exemplary Christians for a number of years; some were just recently baptized. He had begotten them all in Christ.

In a bitter agony of soul Father Jogues stood by and watched the horrible slaughter of his Huron children.

Many had been exemplary Christians for a number of years; some were just recently baptized. He had begotten them all in Christ.

But upon revisiting the spot he could not find the blessed body of René and soon learned that young Iroquois

braves had taken the body and dragged it to the forest nearby. In the spring, Father Jogues found René's fractured skull

and some of his bones. These he reverently kissed and buried beneath the trunk of a tree.

But upon revisiting the spot he could not find the blessed body of René and soon learned that young Iroquois

braves had taken the body and dragged it to the forest nearby. In the spring, Father Jogues found René's fractured skull

and some of his bones. These he reverently kissed and buried beneath the trunk of a tree. The summer of 1645, however, kindled a spark of hope for the despairing Hurons. Not all was shining brightly for the

Iroquois nation. Endless war was sapping the strength of the tribes, as even their victories were costly in manpower.

The summer of 1645, however, kindled a spark of hope for the despairing Hurons. Not all was shining brightly for the

Iroquois nation. Endless war was sapping the strength of the tribes, as even their victories were costly in manpower. On September 24, 1646, the pious priest, accompanied by the young donné, JEAN DE LALANDE,

and several Hurons, embarked on the journey. Eventually, all except for one of the Hurons abandoned the perilous venture.

They had nearly reached Ossernenon, in mid-October, when the anticipated hazards became realities.

A Mohawk war party, on its way to attack the French, captured Father Jogues' little company of three.

They were stripped of clothing, brutally beaten with fists and clubs and hurried along the trail to the Iroquois village.

The peace had been reneged by the Mohawk Bear Clan.

On September 24, 1646, the pious priest, accompanied by the young donné, JEAN DE LALANDE,

and several Hurons, embarked on the journey. Eventually, all except for one of the Hurons abandoned the perilous venture.

They had nearly reached Ossernenon, in mid-October, when the anticipated hazards became realities.

A Mohawk war party, on its way to attack the French, captured Father Jogues' little company of three.

They were stripped of clothing, brutally beaten with fists and clubs and hurried along the trail to the Iroquois village.

The peace had been reneged by the Mohawk Bear Clan.