In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

While some material covered in this chapter of Fr. Northcote's book has already been discussed in Salve Maria Regina No. 160, Fr. Northcote adds many interesting facts, as well as his usual excellent apologetics.

At about two leagues (about 7 miles) distance from the city of Gap, in the district of the High Alps,

lies the little valley of Laus, shut in by wooded mountains and surrounded by other valleys, through which the

river L’Avance winds its way. A more picturesque locality can hardly be imagined. The mountains of Colombis and

St. Maurice appear clothed with forests to their very summits, whilst to the south appear the distant peaks of the

Lower Alps, contrasting in their barren and savage grandeur with the rich vegetation which adorns the hills in the

immediate vicinity of Laus. As the traveler approaches this beautiful region from the valley of L’Avance,

he suddenly discovers the church of Laus lying as it were at his feet, and is reminded by a profusion of pious

monuments which meet his eye at every turn that he is approaching a place specially consecrated to devotion.

Chapels and crosses rise on all sides to commemorate some event in the life of the poor shepherdess to whom the

place owes all its celebrity, and the marvels of whose story receive a certain confirmation from what we may call

a greater marvel still. A simple unlettered peasant girl two centuries ago kept her sheep on these mountains,

and succeeded in transforming a rude and unfrequented wilderness into a vast focus of religious life; leaving

among her native hills so vivid a memory of herself, that time and revolution have not had power to destroy it,

and our own unbelieving century still beholds pilgrims resorting to the spots made memorable by the apparitions

of Our Lady to the shepherdess Benoîte.

At about two leagues (about 7 miles) distance from the city of Gap, in the district of the High Alps,

lies the little valley of Laus, shut in by wooded mountains and surrounded by other valleys, through which the

river L’Avance winds its way. A more picturesque locality can hardly be imagined. The mountains of Colombis and

St. Maurice appear clothed with forests to their very summits, whilst to the south appear the distant peaks of the

Lower Alps, contrasting in their barren and savage grandeur with the rich vegetation which adorns the hills in the

immediate vicinity of Laus. As the traveler approaches this beautiful region from the valley of L’Avance,

he suddenly discovers the church of Laus lying as it were at his feet, and is reminded by a profusion of pious

monuments which meet his eye at every turn that he is approaching a place specially consecrated to devotion.

Chapels and crosses rise on all sides to commemorate some event in the life of the poor shepherdess to whom the

place owes all its celebrity, and the marvels of whose story receive a certain confirmation from what we may call

a greater marvel still. A simple unlettered peasant girl two centuries ago kept her sheep on these mountains,

and succeeded in transforming a rude and unfrequented wilderness into a vast focus of religious life; leaving

among her native hills so vivid a memory of herself, that time and revolution have not had power to destroy it,

and our own unbelieving century still beholds pilgrims resorting to the spots made memorable by the apparitions

of Our Lady to the shepherdess Benoîte.

We shall relate the story of the servant of God simply as it has been preserved, without retrenching anything from the marvelous character attached to it. And let it be remembered that these events did not take place in the dim religious light of mediaeval antiquity, nor are they magnified in our eyes as we behold them through the mist of a long series of centuries. The Shepherdess of Laus lived during a period when the faith of Europe was on the wane, and when men were disposed to anything rather than an over-credulous superstition.

Benoîte Rancurel was born at St. Etienne on the feast of St. Michael, 1647. Her parents were humble peasants who lived by the labor of their hands; and in her twelfth year, Benoîte was put out to service, to keep the sheep of a neighboring farmer, taking her clothes and her Rosary as her only property. During her childhood she had been distinguished for her great tenderness to the poor, and had once earned a sound beating from her mother for giving away food during a time of famine; she had also early evinced a remarkable love of prayer. So much distress prevailed at that time in the country that her master was unable to charge himself with her whole maintenance, and to earn a living Benoîte hired herself out during alternate weeks to a poor widow. The farmer was a brutal character, who up to that time had never been able to keep anyone in his service, but the simplicity and sweetness of Benoîte not only protected her from his cruelty, but had such a softening effect on his hard nature, that in a short time he became another man.

The widow was almost as destitute as Benoîte herself, and the little shepherdess found ample opportunities for exercising her cherished virtue of charity, often sharing her scanty provisions among the six hungry children of the house, and silencing their scruples by the assurance that she herself would have plenty to eat next week. It was thus she grew up in the midst of labor and privation, simple, charitable, and devout, when one day, chancing to hear a sermon wherein the village curé spoke much of the love of the Blessed Virgin for sinners, and the singular protection which She extended to those who consecrated themselves to Her service, Benoîte conceived an ardent desire of being numbered among Her special clients. At the same time the wish sprang up in her heart that she might be found worthy to behold the Blessed Mother of God, of whose mercy and tenderness to the unfortunate She had heard so much.

She was accustomed to frequently lead her sheep to the mountain of St. Maurice,

on the summit of which stood an old ruined chapel, dedicated to that Saint. One day in May of the year 1664,

Benoîte who was then about sixteen years of age, sat down near the ruins to pray her Rosary; she was ignorant

of what had been the nature of the building, and also of the fact that close to it was to be found a spring of water,

though this latter circumstance would have been most welcome news, for during her long days on the barren hillside,

she often suffered greatly from thirst. As she sat thus with her flock grazing around, she perceived an old man

approaching her, of venerable aspect, dressed in red and wearing a beard. He asked her what she was doing there,

to which she replied, with her usual simplicity, that she was watching her sheep and praying to the good God,

but that she was very thirsty.

She was accustomed to frequently lead her sheep to the mountain of St. Maurice,

on the summit of which stood an old ruined chapel, dedicated to that Saint. One day in May of the year 1664,

Benoîte who was then about sixteen years of age, sat down near the ruins to pray her Rosary; she was ignorant

of what had been the nature of the building, and also of the fact that close to it was to be found a spring of water,

though this latter circumstance would have been most welcome news, for during her long days on the barren hillside,

she often suffered greatly from thirst. As she sat thus with her flock grazing around, she perceived an old man

approaching her, of venerable aspect, dressed in red and wearing a beard. He asked her what she was doing there,

to which she replied, with her usual simplicity, that she was watching her sheep and praying to the good God,

but that she was very thirsty. Yet there is water close by you,

said the old man; and he then pointed out the well,

which is still to be seen, and which to this day produces an abundance of excellent water. Benoîte, who had no suspicion

of her visitor, thanked him heartily, and pressed him to eat some of her bread, when he made known to her that he was

St. Maurice, the patron of that mountain, and desired her to lead her flock to a valley near St. Etienne,

where the desire of her heart would be granted to her.

The spot indicated is a sort of ravine which extends from the village to the borders of the forest which crowns the hill; on the eastern side is still pointed out a little cavern where Benoîte was in the habit of retiring to say her Rosary before taking her frugal repast. Hither therefore the little shepherdess directed her steps on the following day, and towards evening she saw standing on a rock, known as Les Fours (The Ovens—a chapel now stands on the spot, erected in 1835), a Lady and Child both of singular beauty. The Lady did not speak to her, and for two months these apparitions were constantly renewed on the same spot, before Benoîte summoned courage to ask Her name. Nevertheless, although not a word had been spoken by her visitor, Her presence filled the heart of Benoîte with joy, and a certain spiritual illumination; but it does not seem certain that she recognized who it was who thus appeared to her, and though on returning home she spoke to all her neighbors of the beautiful Lady she had seen on the rock, she never gave them any reason to suppose that she had been favored with a heavenly vision.

During these two months the flocks showed the same mysterious attraction to the valley of

St. Etienne as their young mistress, a fact the more remarkable as the ravine was rocky and barren,

and the pasturage extremely scanty. The neighbors were not slow to inform the farmer that if he allowed

his sheep to be driven every day to a spot where there was nothing for them to eat, he would lose them all,

and become the laughing-stock of the village. As to the farmer's wife, she also had complaints to make of Benoîte,

who now never returned till late in the evening, and who on her appearance was commonly received with blows.

In obedience to her master's orders therefore, Benoîte conducted her flock to a better pasturage,

lying in a different direction from her favorite ravine, but no sooner had they reached the spot indicated by the farmer,

which afforded an abundance of excellent grass, than of their own accord they set off at full speed to the barren valley

in spite of every effort made by Benoîte to stop them. When this fact was related to the farmer he would not believe it,

and to ensure his orders being carried out, the next day he led his sheep to pasture himself, but had the mortification

of seeing them all trot off in the direction of the forbidden ravine by a sort of instinct which he found himself

unable to overcome. He was forced to admit that there was something in it which he did not understand,

and seeing that the sheep were really in better condition than those of his neighbors, he thenceforth allowed Benoîte

to do as she pleased.

During these two months the flocks showed the same mysterious attraction to the valley of

St. Etienne as their young mistress, a fact the more remarkable as the ravine was rocky and barren,

and the pasturage extremely scanty. The neighbors were not slow to inform the farmer that if he allowed

his sheep to be driven every day to a spot where there was nothing for them to eat, he would lose them all,

and become the laughing-stock of the village. As to the farmer's wife, she also had complaints to make of Benoîte,

who now never returned till late in the evening, and who on her appearance was commonly received with blows.

In obedience to her master's orders therefore, Benoîte conducted her flock to a better pasturage,

lying in a different direction from her favorite ravine, but no sooner had they reached the spot indicated by the farmer,

which afforded an abundance of excellent grass, than of their own accord they set off at full speed to the barren valley

in spite of every effort made by Benoîte to stop them. When this fact was related to the farmer he would not believe it,

and to ensure his orders being carried out, the next day he led his sheep to pasture himself, but had the mortification

of seeing them all trot off in the direction of the forbidden ravine by a sort of instinct which he found himself

unable to overcome. He was forced to admit that there was something in it which he did not understand,

and seeing that the sheep were really in better condition than those of his neighbors, he thenceforth allowed Benoîte

to do as she pleased.

After this time the mysterious apparition was very frequently renewed, and Benoîte was allowed

not only to see, but even to converse with Her whom she still called by no other name than that of her Beautiful Lady.

The matter was talked of in the neighborhood, and one of the magistrates of the province, named Mr. Grimaud,

considered it his duty to interrogate the shepherdess on the subject. Benoîte answered all his questions with

the utmost simplicity, but as she declared herself entirely ignorant who the Beautiful Lady was, the magistrate

was at a loss what to think. The advice he gave her, however, was to make a good Confession and Communion, and then,

the next time she saw the Lady, to approach Her and respectfully enquire Her name. Benoîte followed the wise counsel,

and having prepared herself by a worthy reception of the Sacraments, she summoned the courage to ask the Lady who She was.

I am Mary, the Mother of Jesus,

was the reply, and it is the will of My Son that I should be honored

in this parish, though not on this spot. You will therefore request the Prior to come hither in procession

together with his parishioners.

Benoîte, filled with joy on learning who her Beautiful Lady was,

hastened to communicate her orders to the Prior, who after careful investigation of the facts decided

on giving credence to the heavenly message, and, on August 29, a solemn procession was made to the valley,

at which all the villagers assisted, headed by their pastor.

After this incident, Benoîte was given to understand that she would not again behold Our Lady in that valley;

and it was not until a month later that she was favored with another apparition. This time Our Lady appeared on a

little eminence (Pindreau – image right) near the road leading from Laus to St. Etienne, now marked by

a small oratory, and made known to Benoîte that if she wished to see Her again, she must repair to a little chapel at Laus,

the road to which She pointed out. The next day Benoîte found her way to the chapel in question;

it bore the title of Notre Dame de Bon Rencontre (Our Lady of Good Meeting), and had been built in 1640,

but since then had fallen into partial ruin. The sight of its dusty walls and neglected altar filled Benoîte

with sorrow when she reflected that this was the chosen sanctuary of the Mother of God, but Our Lady made known

to her that before long this poor and squalid building would be replaced by a large church, richly adorned,

and served by many priests, that many poor sinners would be converted here, and that the money required for

such a building would be furnished from the pence of the poor.

After this incident, Benoîte was given to understand that she would not again behold Our Lady in that valley;

and it was not until a month later that she was favored with another apparition. This time Our Lady appeared on a

little eminence (Pindreau – image right) near the road leading from Laus to St. Etienne, now marked by

a small oratory, and made known to Benoîte that if she wished to see Her again, she must repair to a little chapel at Laus,

the road to which She pointed out. The next day Benoîte found her way to the chapel in question;

it bore the title of Notre Dame de Bon Rencontre (Our Lady of Good Meeting), and had been built in 1640,

but since then had fallen into partial ruin. The sight of its dusty walls and neglected altar filled Benoîte

with sorrow when she reflected that this was the chosen sanctuary of the Mother of God, but Our Lady made known

to her that before long this poor and squalid building would be replaced by a large church, richly adorned,

and served by many priests, that many poor sinners would be converted here, and that the money required for

such a building would be furnished from the pence of the poor.

From this time on Benoîte every day visited the chapel, where she spent long hours in prayer,

leaving her flock to the care of Providence. No accident ever befell them, nor did her master oppose her doing

as she chose. The rumor of what had passed very soon spread among the villagers, and induced them also to resort

to the little oratory in ever-increasing numbers. Many of these, touched by grace, devoutly prepared themselves

for the Sacraments, and it was found necessary to engage priests to attend on the spot to hear the confessions

of the pilgrims. The chapel very soon became too small to contain the hundreds who daily presented themselves,

and an altar for the celebration of Mass had to be erected out of doors, while the priests heard confessions

under the rocks and trees of the valley. Whole parishes came hither in procession from many miles' distance,

thirty-five such processions arriving on a single day. Some of these had journeyed on foot for fourteen hours,

and this manifestation of popular devotion took place before any official examination had been made into the

circumstances to which it owed its origin. Many signal graces, both spiritual and temporal, were granted to

the prayers of the pilgrims; miraculous cures, and striking conversions were of continued recurrence.

From this time on Benoîte every day visited the chapel, where she spent long hours in prayer,

leaving her flock to the care of Providence. No accident ever befell them, nor did her master oppose her doing

as she chose. The rumor of what had passed very soon spread among the villagers, and induced them also to resort

to the little oratory in ever-increasing numbers. Many of these, touched by grace, devoutly prepared themselves

for the Sacraments, and it was found necessary to engage priests to attend on the spot to hear the confessions

of the pilgrims. The chapel very soon became too small to contain the hundreds who daily presented themselves,

and an altar for the celebration of Mass had to be erected out of doors, while the priests heard confessions

under the rocks and trees of the valley. Whole parishes came hither in procession from many miles' distance,

thirty-five such processions arriving on a single day. Some of these had journeyed on foot for fourteen hours,

and this manifestation of popular devotion took place before any official examination had been made into the

circumstances to which it owed its origin. Many signal graces, both spiritual and temporal, were granted to

the prayers of the pilgrims; miraculous cures, and striking conversions were of continued recurrence.

At length in September, 1665, the ecclesiastical authorities felt it their duty to investigate the whole affair. M. Lambert, the Vicar-General of the diocese of Embrun, accompanied by twenty-two other ecclesiastics of rank and learning, proceeded to Laus to initiate a juridical inquiry. Benoîte was subjected by them to a severe examination. The Vicar-General made her understand that they were not come there to authorize her visions and foolish fancies, and that if she was detected of any imposture, she would be severely punished. One after another the examiners then attacked her with questions, arguments, and even with ridicule; they strove now to embarrass and now to intimidate her, but the simplicity and integrity of the poor shepherdess withstood the trial, and she replied to their questions with a precision and modest self-possession that filled them with surprise.

Providence had so ordered it, that the Vicar-General and his companions should themselves be eyewitnesses of a striking

miracle wrought during their visit. Twice they had made preparations to depart, and each time violent torrents of

rain had obliged them to return to their lodgings. It seemed as if against their wills they were to be detained at Laus,

in order to be able to bear witness to one of those prodigies the truth of which they were as yet unwilling to allow.

On the very day they were to leave, a poor crippled woman, named Catherine Vial, who had for years been entirely deprived

of the use of her limbs which were withered and bent under her, was suddenly restored to strength on the ninth day of a

novena which she had made to Notre Dame du Laus. Every day during the novena, the Vicar-General had seen her carried to

and from the chapel, and it was while he himself was offering Mass at the altar, that he now beheld her enter,

walking alone and without support, and heard the bystanders exclaiming,

Providence had so ordered it, that the Vicar-General and his companions should themselves be eyewitnesses of a striking

miracle wrought during their visit. Twice they had made preparations to depart, and each time violent torrents of

rain had obliged them to return to their lodgings. It seemed as if against their wills they were to be detained at Laus,

in order to be able to bear witness to one of those prodigies the truth of which they were as yet unwilling to allow.

On the very day they were to leave, a poor crippled woman, named Catherine Vial, who had for years been entirely deprived

of the use of her limbs which were withered and bent under her, was suddenly restored to strength on the ninth day of a

novena which she had made to Notre Dame du Laus. Every day during the novena, the Vicar-General had seen her carried to

and from the chapel, and it was while he himself was offering Mass at the altar, that he now beheld her enter,

walking alone and without support, and heard the bystanders exclaiming, a miracle! a miracle! Catherine Vial is cured!

I myself was serving his Mass,

writes M. Gaillard, the Grand-Vicar of Gap,

who has preserved all these particulars, and I perceived he was so overcome that he could hardly finish the Last Gospel,

and the cards on the altar were moistened with his tears.

(A month later the parish of St. Julien to which

Catherine belonged, made the pilgrimage to Laus in procession, their banner being carried by Catherine herself.)

A fresh inquiry was now set on foot into the truth of this fact; not only the woman herself and her family, but the two surgeons who had attended her, were rigorously questioned. The latter were both Calvinists, and when they heard of the proposed novena, had declared themselves willing to become Catholics if they should see her ever able to walk again. They had seen her returning from the chapel, and not only attested that her disease had been incurable by human means, but avowed themselves convinced by that they had seen, and ready to abjure their heresy. The record of these events was drawn up by the Vicar-General, who desired that a Te Deum should be chanted in the chapel in thanksgiving for so signal a grace, and who became from that time the firm protector and friend of the shepherdess, and of the work of which she was chosen as the instrument.

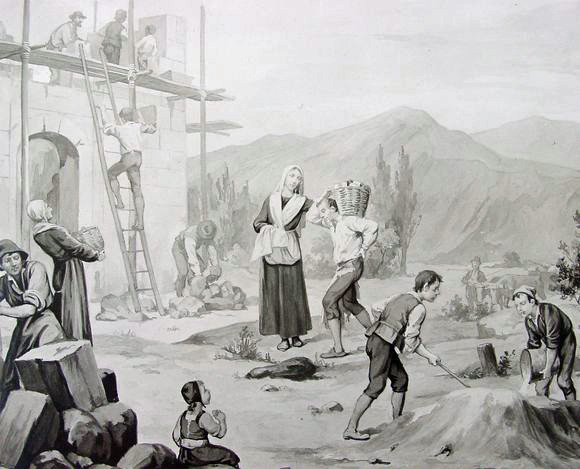

And in fact poor Benoîte was often subjected to trials, wherein she stood in need of protection. Many persons of rank and influence regarded her as an impostor, and attempts were made not only to bring her into discredit, but even to have her driven from Laus and consigned to prison. In spite of this hostility however, the pilgrimages continued to increase, and four years after the first apparition of Our Lady in the chapel of Laus, M. Lambert decided on erecting a church on the site of the chapel, which was altogether inadequate for the wants of the pilgrims. M. Gaillard met him at Laus in order to consult with him on the subject, and has left an account of what passed on the occasion. The plan of the Vicar-General was to build a small church, seven or eight fathoms long (a ‘fathom’ is six feet), containing two or three altars. On the representation of M. Gaillard that it ought to be at least fifteen fathoms, he replied that he had never contemplated such an undertaking, that the pilgrimages would probably last at most a dozen years, and would then die away, and that it would be impossible to find funds for so large a building. After some demur he at last consented that the foundations should be dug for twelve fathoms, and entrusted the direction of the works to M. Gaillard.

I remember very well,

he writes, that when we began to dig the foundations we had no money;

we had some alms-boxes made, and M. Naz, one of the directors of the works, asked alms with one of these.

A poor woman dressed in rags, to whom one would have felt disposed to give relief if one had met her on the road,

came gently behind him, and slipped in a Louis d’or (a small gold coin weighing just under 1/4 of an ounce);

that was sufficient for the first week. The next week we had ten crowns, and so it went on, so that we were never

in want either of money, material, or workmen; it was the 'pence of the poor' that built the entire church,

though in point of fact it cost more than 15,000 livres (pounds).

The pilgrims aided the rising work with their alms and their labor. It became the custom, whenever a parochial

procession visited Laus, for every member of it – man, woman, and child – to bring a stone. A year was devoted to

collecting the necessary materials, and then the building began in good earnest. We have said that M. Gaillard

had originally proposed to M. Lambert that the length of the church should be fifteen fathoms, and singularly

enough the additional length was added by order of the Vicar-General, who on coming to survey the works found

that by some unaccountable omission no provision had been made in the plans for a sanctuary; he therefore ordered

one to be added to the erection then in progress, and in less than four years the church was completed with the

exception of the portico – which, however, was built at the expense of the Archbishop of Embrun, then Ambassador

at Madrid, who having recovered from a dangerous sickness in consequence of a vow made to Notre Dame du Laus,

wished to make this portico his thank-offering.

The pilgrims aided the rising work with their alms and their labor. It became the custom, whenever a parochial

procession visited Laus, for every member of it – man, woman, and child – to bring a stone. A year was devoted to

collecting the necessary materials, and then the building began in good earnest. We have said that M. Gaillard

had originally proposed to M. Lambert that the length of the church should be fifteen fathoms, and singularly

enough the additional length was added by order of the Vicar-General, who on coming to survey the works found

that by some unaccountable omission no provision had been made in the plans for a sanctuary; he therefore ordered

one to be added to the erection then in progress, and in less than four years the church was completed with the

exception of the portico – which, however, was built at the expense of the Archbishop of Embrun, then Ambassador

at Madrid, who having recovered from a dangerous sickness in consequence of a vow made to Notre Dame du Laus,

wished to make this portico his thank-offering.

Although the erection of this magnificent church on a spot so humble seemed in itself to confirm the truth of the revelation made to Benoîte, the success of her work only increased the number and malice of her enemies. After the death of M. Lambert, which took place very soon after the consecration of the church, certain members of the chapter of Embrun revived all the old accusations against the shepherdess of Laus. They caused a paper to be affixed to the church door, threatening with excommunication any priest who dared to offer Mass there, or any lay person who received the Sacraments within its walls. It is needless to say that an interdict of such a character, and from such an authority, was altogether unlawful – neither did those who published it ever dare to carry its threats into effect.

A new Vicar-General was soon appointed who summoned Benoîte to Embrun, and subjected her to

a second examination, which terminated in his declaring that the pilgrimage of Notre Dame du Laus was the

work of God, and that the innocence and sanctity of Benoîte were above suspicion. The newly appointed Archbishop,

Monseigneur de Genlis, even visited Laus in person, and on beholding the church crowded with its devout worshipers,

exclaimed aloud, Vere Dominus est in loco isto

(Truly the Lord is in this place!)

He also questioned Benoîte closely, and wrote down her answers with his own hand, declaring afterwards that

he had never witnessed more simple or more solid piety.

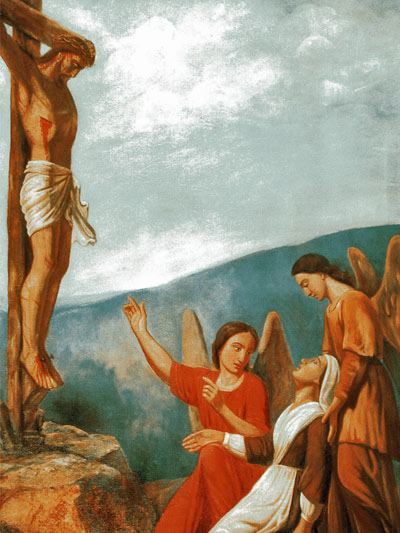

In fact, the reputation for sanctity which the shepherdess of Laus enjoys does not by any means rest merely on the

apparitions with which she was favored. Her devotion to Jesus and His Holy Mother was not alone evinced by prayers

and ecstasies, but by the far surer tokens of humility, disinterestedness, charity, and forgiveness of injuries.

The work to which she devoted herself was to labor by prayer and severe austerities for the conversion of sinners.

This idea had never left her soul since she had one day been granted a vision of her Divine Lord hanging on the Cross:

this then was what He had suffered for sinners, and this was the love He bore them! Such were the thoughts which the

piteous spectacle engraved on the heart of Benoîte, and from that hour her sole desire was to suffer and to love with Him.

In fact, the reputation for sanctity which the shepherdess of Laus enjoys does not by any means rest merely on the

apparitions with which she was favored. Her devotion to Jesus and His Holy Mother was not alone evinced by prayers

and ecstasies, but by the far surer tokens of humility, disinterestedness, charity, and forgiveness of injuries.

The work to which she devoted herself was to labor by prayer and severe austerities for the conversion of sinners.

This idea had never left her soul since she had one day been granted a vision of her Divine Lord hanging on the Cross:

this then was what He had suffered for sinners, and this was the love He bore them! Such were the thoughts which the

piteous spectacle engraved on the heart of Benoîte, and from that hour her sole desire was to suffer and to love with Him.

She often prolonged her fasts for many days, and observed a continual abstinence, living only on bread and a little fruit. She watched the greater part of every night, and only slept on the bare ground. Thrice a week for the space of thirty years she went barefoot to that spot on the road between Laus and Avançon, where the vision above spoken of had appeared to her, and spent many hours there, weeping and praying for the conversion of sinners, and all the rest of her time she devoted herself to the service of the pilgrims. Many were the souls who owed their lasting conversion to her charitable exhortations, and not a few have borne witness to the marvelous gift which she possessed of penetrating into the secrets of their consciences. Of her other mortifications, in the shape of hair-cloths, disciplines, chains, and endurance of excessive cold, we will only add, that she was at last warned by Our Lady to moderate their excess, and that, by the testimony of all who knew her, she made her life one long-continued martyrdom.

Far from dying out at the end of a dozen years, as M. Lambert had expected,

the devotion to Notre Dame du Laus constantly assumed larger proportions. At the suggestion of Benoîte,

regular retreats were established eight times a year, which were conducted according to fixed rules,

and were the means of effecting a great revival of solid piety. And what is more, this religious movement

of which Laus had become the center, survived more than one crisis which threatened the entire destruction

of the new Sanctuary. In 1692 the troops of the Duke of Savoy entered Dauphiny, and laid siege to Embrun.

Benoîte with many of her fellow-villagers took refuge at Marseilles, whilst the hostile forces overran the

country, pillaged the church of Laus, and destroyed whatever they were not able to carry off. When she was at

length able to return to her native valley, the servant of God was profoundly afflicted at beholding the

profanation which had been offered to the Sanctuary. The house of the priests had been burnt, and the marble

altars dashed to pieces; everything was in ruins and desolation, but Benoîte did not lose heart.

We have more than we had twenty-eight years ago,

she said, and she at once set about the work of restoration.

Once again this was accomplished with the pence of the poor; no rich benefactors came forward; but one village

contributed wood, another stone, a third wagons and horses. Benoîte herself directed and encouraged their labors,

and in a few months' time the church of Laus presented even a better appearance than it had done before the invasion.

A more serious danger menaced the prosperity of Laus, when, on the death of the priests who had up to that time served the Sanctuary, others were appointed of Jansenistic principles, who no sooner found themselves in possession of the place than they used every effort to put a stop to the pilgrimage. They caused all the oratories erected in the different localities of Laus to be destroyed, they drove away the pilgrims, and publicly preached from the pulpit against the popular devotion exhibited towards Our Lady; and not only did they forbid Benoîte to discharge her accustomed offices in the holy chapel – the altar and linen of which she had hitherto had charge of – but they refused to admit her to the Sacraments, put her in a sort of confinement, and only allowed her to hear Mass once a week. This persecution lasted for twenty years, during all of which time Benoîte submitted to their injurious treatment with her usual docility and resignation; the only order which she refused to obey, was that she should use her influence with the people to deter them from resorting to Laus, for this would have been, as she considered, a direct disobedience to the Divine commands. Her only weapons of defense were prayer and confidence, and they did not fail to effect her deliverance. In 1712 the Archbishop of Embrun removed the priests of Laus, and confided the care of the Sanctuary to a congregation of missionaries, knows as that of Notre Dame de Sainte-Garde, and no sooner was the change effected than everything returned into its former channel; the pilgrimage became more frequented than ever, and the fruit of souls more marvelous and abundant. Benoîte, who had lived to see this happy fulfillment of her prayers and ardent desires, understood that her work was ended, and that she had nothing more to do but to prepare for death. She expired on the Feast of the Holy Innocents, 1718, at the age of seventy-one years, fifty-six of which had been spent in founding and supporting the Sanctuary which seemed to have been entrusted to her guardianship by the Mother of God.

Her body lies buried in front of the high altar of Laus, and is covered with a stone, bearing the following inscription:

Her body lies buried in front of the high altar of Laus, and is covered with a stone, bearing the following inscription:

Tombeau de la Sœur Benoîte, Morte en odeur de sainteté Le 28 dècembre 1718.

Tomb of Sister Benoite, Died in the odor of sanctity December 28, 1718.

The title of Sister is here bestowed on her, in consequence of her having been associated to the Third Order of St. Dominic. Eighty years later the tomb was opened and the body was discovered perfectly incorrupt. The voice of the people has long since expressed their pious conviction of her heroic sanctity, and it is understood that the necessary documents have been drawn up by the ecclesiastical authorities with the view of introducing the process of her beatification at Rome.

The devotion of the people in no degree slackened after the death of Benoîte.

The missionaries continued their pious labors, and pilgrims continued to resort to Laus in great

numbers up to the year 1791, when the revolution came once more to lay waste the holy sanctuary.

The priests were driven away, all the ornaments of the church seized, the church itself shut up,

and the houses for the use of the pilgrims either burnt or sold. Frightful sacrileges were perpetrated by

the brutal ruffians who carried out the orders of their masters, and who destroyed and desecrated whatever

they were unable to carry off. They were directed to efface every memorial of piety in the neighborhood,

to demolish all the crosses and oratories in the surrounding valleys, and to purge the country of their odious presence,

and these orders they carried out to the letter. But they were unable to destroy the devotion which had struck

its roots into the hearts of the people. All through the miserable days of the Reign of Terror,

the peasants continued to resort to their ruined and desolate sanctuary, to bring thither their sick,

and to invoke the aid of the Mother of God in all their tribulations. On occasion of a great drought

which threatened to destroy all hope of a harvest, the surrounding villages even insisted on making a

solemn public procession to Laus, as in former times, and their faith was rewarded by a fall of rain,

which restored their lands to fertility.

At last, when order was restored, in 1802, Msgr. Miollis, Bishop of Digne, purchased and restored the church, and reopened it for public worship. Three of the surviving missionaries returned to their old post, and at once the devotion of the people, forcibly restrained for a time, broke forth with a greater enthusiasm than ever. Ocular witnesses have described the scenes they themselves witnessed in 1804, when the entire church was blocked up by the crowds of penitents, and the priests in attendance were found insufficient to satisfy the requirements of the pilgrims. In course of time a new congregation of missionary priests was established at Laus, the retreats and other pious exercises were revived, and oratories and chapels erected on the site of those destroyed by the revolutionaries. Eventually Notre Dame du Laus probably attracted a greater number of pilgrims than even during the days of Benoîte, and it was no uncommon thing on the greater feasts to see altars erected out of doors for the celebration of Mass, in order to accommodate the vast crowds that overflowed the spacious church. The average number of those who visited Laus in the course of the year was 80,000, of which the greater proportion attended at the Feast of Pentecost, and during the October retreat. On those occasions as many as thirty-six or even forty priests were to be seen attending in the confessionals, where they often had to remain during the entire night. Many extraordinary graces have been received at these times, of which testimony is to be found in the ex-voto offerings which cover the walls.

The visitor to Laus would find the memory of Benoîte still fresh in the breasts of the people,

and all the surrounding valleys filled with pious monuments attesting their faith in those apparitions which

were vouchsafed to her by the Mother of God. The grotto where the little shepherdess was accustomed to pray,

the rock where Our Lady first appeared to her, the chapel of Notre Dame d’Erable, where, according to her history,

she had to sustain many assaults from the evil one; another, called the Chapel of the Angel,

where her guardian angel is said to have appeared to her in visible form; the Oratory in Pindreau,

on the spot where the Blessed Virgin first directed her to go to Laus, and finally, that of the Cross,

on the road where she beheld the Vision of Jesus Crucified (image right) – all these and more are numbered among the

holy places of Laus. Swept away once by war, and again by anti-religious revolution, they have each

time been restored, and not merely the material buildings have reappeared, but with them the faith,

the devotion, the indescribable atmosphere of piety which seems to hang about this celebrated place of pilgrimage.

The visitor to Laus would find the memory of Benoîte still fresh in the breasts of the people,

and all the surrounding valleys filled with pious monuments attesting their faith in those apparitions which

were vouchsafed to her by the Mother of God. The grotto where the little shepherdess was accustomed to pray,

the rock where Our Lady first appeared to her, the chapel of Notre Dame d’Erable, where, according to her history,

she had to sustain many assaults from the evil one; another, called the Chapel of the Angel,

where her guardian angel is said to have appeared to her in visible form; the Oratory in Pindreau,

on the spot where the Blessed Virgin first directed her to go to Laus, and finally, that of the Cross,

on the road where she beheld the Vision of Jesus Crucified (image right) – all these and more are numbered among the

holy places of Laus. Swept away once by war, and again by anti-religious revolution, they have each

time been restored, and not merely the material buildings have reappeared, but with them the faith,

the devotion, the indescribable atmosphere of piety which seems to hang about this celebrated place of pilgrimage.

At the close of one of the retreats, one of those who had assisted at its exercises exclaimed

with great emotion, Why do they not preach like this in our parish?!

One of the missionaries who

overheard him replied, In your parish, very probably they preach not only as well, but a great deal better

than they do here; only here, there is an Invisible Preacher, Who speaks to the heart.

And these few words

contain the secret of that wonderful influence which is felt by those who visit holy sanctuaries in the true

spirit of pilgrimage. God makes Himself felt there as the Invisible Preacher; He draws souls to these His secret places,

that He may speak to their hearts, and the long list of miraculous cures and graces which fill the chronicles of such

sanctuaries are but a feeble exterior token of far more numerous and prodigious graces granted invisibly to penitent

and believing souls.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com