In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

While some material covered in this chapter of Fr. Northcote's book has already been discussed in Salve Maria Regina No. 99, Fr. Northcote adds many interesting facts, as well as his usual excellent apologetics.

This celebrated sanctuary stands among rocky mountains in the Canton of Schwyz, in the midst of what, in the ninth century of the Christian era, was a savage wilderness. Here, about the year 840, a Benedictine monk named Meinrad, who had formerly filled the office of scholasticus in one of the abbeys dependent on that of Reichenau, took refuge from the applause of his own scholars, and the veneration of those who regarded him as a saint. His first retreat had been a little hut erected on Mount Etzel near Altendorf, on a spot still marked by a chapel where the pilgrims to Einsiedeln are accustomed to make the first station. But the world found him out here, and men of all countries resorted in such crowds to the cell of the poor anchorite, that to escape their importunities he one day took his Image of the Blessed Virgin, his Missal, the Rule of St. Benedict, and the works of Cassian, and with these for his sole companions he plunged into the dense Helvetian forest to find out some place where he might more effectually conceal himself from the world.

He found it at Einsiedeln, where he built himself a cell and in an adjoining chapel (built for him by Hildegarde, daughter of the Emperor Ludwig and abbess of a convent of nuns at Zürich) he deposited the Image before which he had received many miraculous favors. In this retreat he sustained many of those assaults with which the enemy of souls so often persecuted the ancient solitaries. Frightful tempests raged in the desolate wilderness, and the pines of the old forest were torn up by the mountain winds, and sometimes assumed gigantic proportions, and seemed as if endowed with life. Sometimes the whole forest seemed in flames around his cell; but in the midst of these and yet more horrible trials, Meinrad remained unmoved, and overcame every attack with the unfailing weapon of prayer. One of his brother monks of Reichenau who had discovered his retreat, and who was occasionally permitted to visit him, drew near his cell one night and perceived a brilliant light proceeding from the little chapel. Looking in he saw Meinrad kneeling on the altar step reciting the night office, whilst a young child surrounded by brilliant rays supported his book, and recited with him the alternate verses. The monk dared not intrude, but returning to his monastery made known to the brethren that Meinrad's solitary cell was visited by angels.

Twenty-six years were thus spent by the holy hermit in the mingled exercise of contemplation and apostolic labor. The rustics of the neighborhood sought him out and profited by his instructions, and even the wild creatures of the surrounding forest forgot their savage nature and resorted to his cell. Two crows in particular came to him every day to be fed from his hand, and returned his kindness to them by a fidelity which history has not failed to commemorate.

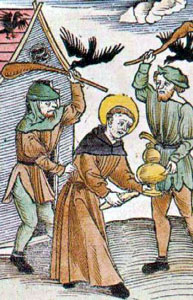

At last, however, the idea suggested itself to two miscreants named Richard and Peter,

that hidden treasures were concealed in Meinrad's poor hermitage, and they accordingly conceived the plan

of assassinating him. They made their way to his cell, and as they passed through the forest,

the birds raised a frightful clamor as though to warn their benefactor of the approach of danger.

But Meinrad had already received warning of his approaching fate from a higher source, and addressing his murderers,

he said to them, I well know wherefore you are come hither, but you shall not slay me till you have received my

blessing and pardon. When I am dead light these two candles and place one at the head and the other at the foot

of my couch, and then fly quickly lest you be discovered by those who come hither to visit me.

Unsoftened by these words the ruffians fell on him and dashed out his brains, and as he breathed his last an odor

of inexpressible fragrance diffused itself through the cell. Having searched everywhere, and found no treasure,

they were about in their haste to leave the spot without obeying the Saint's last injunction, when,

says the legend, they beheld the candles lit of themselves. Filled with terror at this marvel they

took to flight, but as they hastened through the forest, their hands and clothes dyed with the blood

of their victim, the two crows pursued them, pecking at them, and flapping them with their wings.

The body was discovered in the course of the day by a poor carpenter, who had been in the habit of

often visiting Meinrad in his cell, and the news soon spread that the Saint had been murdered,

and that two men supposed to be the assassins had been seen hurrying on the road to Zürich.

The crowd which the news had assembled together, set out in that direction, and arriving at Zürich,

were directed to the house where the murderers had taken refuge, by beholding the two crows furiously

pecking at the windows of an inn, where they obstinately remained in spite of every effort of the

servant-girl to drive them away. The carpenter recognized the birds, and the murderers being seized

confessed their crime and were broken on the wheel. At the moment of execution, it is said that the

crows appeared hovering over the scaffold, and the memory of these events is still preserved in Zürich,

where one of the inns bears the sign of the Two Faithful Crows. This story has been reproduced in sculpture

and illuminations in a great number of churches; the abbey of Einsiedeln still bears two crows on its amorial shield,

and the custom long prevailed among the servants of the abbey of every year catching a crow, which is taken great

care of during the winter, and set at liberty again at the approach of spring.

Unsoftened by these words the ruffians fell on him and dashed out his brains, and as he breathed his last an odor

of inexpressible fragrance diffused itself through the cell. Having searched everywhere, and found no treasure,

they were about in their haste to leave the spot without obeying the Saint's last injunction, when,

says the legend, they beheld the candles lit of themselves. Filled with terror at this marvel they

took to flight, but as they hastened through the forest, their hands and clothes dyed with the blood

of their victim, the two crows pursued them, pecking at them, and flapping them with their wings.

The body was discovered in the course of the day by a poor carpenter, who had been in the habit of

often visiting Meinrad in his cell, and the news soon spread that the Saint had been murdered,

and that two men supposed to be the assassins had been seen hurrying on the road to Zürich.

The crowd which the news had assembled together, set out in that direction, and arriving at Zürich,

were directed to the house where the murderers had taken refuge, by beholding the two crows furiously

pecking at the windows of an inn, where they obstinately remained in spite of every effort of the

servant-girl to drive them away. The carpenter recognized the birds, and the murderers being seized

confessed their crime and were broken on the wheel. At the moment of execution, it is said that the

crows appeared hovering over the scaffold, and the memory of these events is still preserved in Zürich,

where one of the inns bears the sign of the Two Faithful Crows. This story has been reproduced in sculpture

and illuminations in a great number of churches; the abbey of Einsiedeln still bears two crows on its amorial shield,

and the custom long prevailed among the servants of the abbey of every year catching a crow, which is taken great

care of during the winter, and set at liberty again at the approach of spring.

The death of Meinrad took place in 863. His body was at first taken to Reichenau, where it remained until the year 1039, but in the meantime his little hermitage, the chapel in which he had been accustomed to pray, and the holy Image of Our Lady deposited there by his hands, were devoutly visited by vast numbers of pilgrims, and became the scenes of stupendous prodigies. Forty years passed without anything being done to prevent the hermitage itself from falling into ruins; but in 903, Benno, a canon of Strasburg, having made a pilgrimage thither, was so touched by devotion that he resolved to bid the world farewell, and to found a community of hermits on the spot already consecrated by the life and death of a Saint.

The cells of the new hermits, built only of wood and moss, were accordingly constructed around Meinrad's chapel, which from this time received the name of Einsiedeln (this name is derived from the German word for hermit). In 927 Benno was forced to accept the bishopric of Metz, where his courageous efforts to reform the vices of his people raised a tumult against him, in the course of which his enemies dragged him from his palace to the public square, where they inhumanely tore out his eyes, and then banished him from his see. The crime was punished as it deserved by the Emperor Heinrich I, but Benno gladly took occasion of resigning his dignity and once more retiring to his beloved solitude, where thirteen years later, his body was laid to rest, at the foot of Our Lady's altar.

Among those whom he had trained in the path of perfection was St. Eberhard – a Swabian noble, who conceived the design of converting the hermitage into an abbey, of which in 940 he became the first abbot. A magnificent church rose over the chapel of Our Lady, the Rule of St. Benedict was introduced, and thus began the rich and famous abbey afterwards governed by a long line of princes of the Holy Roman Empire. (The first abbot who enjoyed the rank of Prince of the Empire, conferred on him by the Emperor Otto the Great, was an Englishman by birth. Gregory, the third abbot in succession from St. Eberhard, is said to have been a son of King Edward the Elder; he was certainly of the Anglo-Saxon royal blood, for the Empress Editha, first wife of Otto, was daughter to King Edward, and in the chronicles of Einsiedeln, Gregory is spoken of as her relative.)

It would take us far beyond our limits to follow the history of the abbey through succeeding centuries; but the legendary history of the consecration of its church is too famous to be passed over in silence. The ceremony was to have been performed by Konrad, Bishop of Konstanz, who arrived at Einsiedeln for that purpose on September 14, 948, accompanied by St. Ulrich of Augsburg, and a crowd of nobles and ecclesiastics. The eve of the day fixed for the dedication was spent by the bishop and the other clergy in watching and prayer. Suddenly as they prayed, they beheld the church illuminated with marvelous splendor, and filled with a heavenly throng, in the midst of which Our Lord Himself appeared standing at the altar, celebrating the sacred rite. Konrad who himself relates the story in his book entitled De Secretis Secretorum, informs us that the text of the Sanctus as chanted by the Angels ran as follows: Sanctus Deus in aula gloriosæ Virginis, miserere nobis. Benedictus Mariæ Filius, in æternum regnaturus qui venit in nomine Domini, Hosanna, etc. (Holy God, in the womb of the glorious Virgin, have mercy on us. Blessed be the Son of Mary, He Who is to reign in eternity, Who cometh in the Name of the Lord, Hosanna, etc.)

When day broke the multitude assembled and waited long and impatiently for the Bishop to commence the ceremony. When at last he appeared he declared to them what he had witnessed during the night; nevertheless, at length he yielded to their persuasion that it was but a dream, and entering the church he prepared to begin the ceremony, when an unknown voice was heard repeating the words: Cessa, cessa frater! Capellus divinitus consecratus est. (Cease, cease, brother! The Chapel is divinely consecrated.)

We will only add that sixteen years later, Konrad and Ulrich being at Rome, solemnly deposed to the truth of this narrative, which was published to the world in a bull of Pope Leo VIII. In this bull it was forbidden ever to reconsecrate the church, and large indulgences were granted to those who should devoutly and with contrite hearts perform the pilgrimage to so holy a place.

In 1039 Prince Abbot Embricius succeeded in obtaining the translation of the relics of St. Meinrad from the Abbey of Reichenau, and the pilgrimage, which was already a famous one, especially in Germany and Switzerland, thenceforward attracted yet larger numbers, and became so popular that not even the disastrous revolution of the sixteenth century had power to interrupt it. Even the heretics themselves never entirely lost their veneration for Our Lady of Ensiedeln, and Scotti, at that time the Apostolic Nuncio in Switzerland, affirms it as a well-known fact that hundreds of those who profess the "new opinions" every year visited this sanctuary, irresistibly drawn thither by the sanctity of the place, and the force of long-established habits. The chief concourse takes place on the anniversary of the miraculous consecration of the church, namely the 14th of September, and during the ensuing fortnight, when as many as 100,000 pilgrims have been known to assemble. The rocky mountain-road leading to the Abbey is often dyed with the blood of those who piously ascend it barefoot; and on first sight of the towers of this venerable Abbey, it is impossible not to be conscious of that peculiar devotion, or as one writer expresses it, of that sacred dread, which is inspired on the near approach of holy ground.

Standing nearly 3,000 feet above sea level, and forming the central point where two valleys meet, the situation of Einsiedeln is picturesque in the extreme. A village of several thousand inhabitants has sprung up around the Abbey, which, in its present form, is not of very ancient date, for it has been repeatedly burned down and rebuilt, and the greater part of the present edifice was constructed in 1704. It is remarkable, however, that in each of the five fires (those in 1028, 1214, 1465, 1509, and 1577) which reduced the rest of the building to ashes, the holy chapel (Gnadenkapelle) which is enclosed within the great church escaped injury. On entering the church it immediately strikes your eye, standing in the very midst of the larger building, and contrasting by its somber appearance with the magnificence that appears around it on every side. So greatly was this chapel revered that it was jealously preserved in its original form up to the year 1467, when, in consequence of its narrow escape a third time from being consumed, Burchard, Bishop of Konstanz, ordered that it should be vaulted with stone, and protected outside with stone columns and pilasters. In 1617 it was entirely encased in marble, by order of Marcus Sitticus, the celebrated Archbishop of Salzburg, and succeeding prelates have yet further adorned it with statues and bas-reliefs.

The interior of the chapel once blazed with riches. Precious marbles still cover the walls of the further extremity where the miraculous image of Our Lady, the rude and Gothic appearance of which attests its antiquity, is still preserved, having escaped destruction amid all the convulsions of the revolutionary period. The face of the altar on which it stands was once adorned with a silver bas-relief representing the miraculous dedication and sixteen large wax tapers were kept constantly burning before it at the expense of the sixteen Catholic cantons of Switzerland. Both altar frontal and candles have disappeared, but on the altar appears and exceedingly rich tabernacle enclosing the head of St. Meinrad, the only portion of his relics which has been preserved from the profanation of the revolutionary hordes. Five lamps presented by various European sovereigns used also to burn continually before the image, but these too have been removed.

In former times Mass was celebrated in this Chapel continually from four in the morning until ten,

when the high Mass was celebrated in the choir; then there followed another low Mass within the Holy Chapel,

and from that time, wrote a pilgrim, you would hear nothing but the voice of the pilgrims incessantly

repeating the Rosary, as band by band successively entered the Chapel.

This would last until Vespers,

after which the monks every day would visit the Holy Image singing the Salve Regina in procession.

As soon as they had left the Chapel, it would be once more besieged by pious crowds, who may have been

seen praying there until nine o'clock, when the church was closed. It has been said that nothing could

exceed the devotion exhibited by those pilgrims; you may have seen them in every attitude of prayer,

some prostrate, others kneeling with their arms extended in the form of a cross; they were from all

ranks and all nations, but perhaps the larger proportion were from the Tyrol, when it was truly Catholic soil.

We shall not attempt to trace the history of the pilgrimage, or to count up the illustrious names that appear on the list of those who have offered their devotion at this celebrated shrine. To do so would be to enumerate half the crowned heads, the canonized Saints, and the Catholic men of learning of a thousand years. It will be more interesting to the reader if we say something of the manner in which the miraculous shrine was preserved during the revolutionary crisis of 1798.

On the 30th of April in that year, the French troops entered the canton of Schwyz, and without waiting for their nearer approach the monks hastened to remove the Image, which they succeeded in transporting to the neighboring valley of Alpthal, on the very day that the French entered Einsiedeln. The curé of this place was required to give up the statue on pain of having a detachment of troops quartered in his village. But the brave curé, while negotiating with the commandant, caused the Image to be secretly carried away to a chalet among the mountains, whence it was later transferred to a convent of nuns at Bludenz near Vorarlberg. Placidus Keller, an old servant of the convent, was trusted with the honorable but dangerous task of conveying it thither. Furnishing himself with a peddler's pack, he covered the Image with handkerchiefs and other small wares, and with this strapped on his back, he boldly made his way through the very lines of his enemies, to whom he more than once had to display his merchandise. On these occasions, with the utmost nonchalance, he appeared absorbed only with anxiety to strike a profitable bargain.

Once safe at Bludenz all necessity of secrecy was considered at an end, and the Image

being exposed in the public square before the convent, an immense demonstration of popular devotion took place,

and whole villages came even from the Tyrol, during a four days' solemnity that was celebrated in thanksgiving.

In the October following it was judged prudent to remove the Image into the Tyrol, and to prevent the possible

danger of the inhabitants laying claim to the treasure on the ground of long possession, it was never allowed to

remain for any length of time in one place, but was taken first to Imst, then to Häle, from thence to Drieste,

and was finally brought back to Bludenz. During these journeys one of the monks of Einsiedeln, named Konrad Tanner,

always accompanied it as its guardian.

Once safe at Bludenz all necessity of secrecy was considered at an end, and the Image

being exposed in the public square before the convent, an immense demonstration of popular devotion took place,

and whole villages came even from the Tyrol, during a four days' solemnity that was celebrated in thanksgiving.

In the October following it was judged prudent to remove the Image into the Tyrol, and to prevent the possible

danger of the inhabitants laying claim to the treasure on the ground of long possession, it was never allowed to

remain for any length of time in one place, but was taken first to Imst, then to Häle, from thence to Drieste,

and was finally brought back to Bludenz. During these journeys one of the monks of Einsiedeln, named Konrad Tanner,

always accompanied it as its guardian.

In 1803 the terrible crisis having happily passed over, it was resolved to restore the holy Image to its own sanctuary. It was secretly brought down the Rhine, conveyed through Switzerland, and deposited in the chapel of St. Meinrad on Mount Etzel. From thence it was conducted to Einsiedeln in a sort of triumphal procession, and replaced on the altar where it had reposed for so many centuries.

The five years that had intervened, if they had witnessed the spoliation of its material treasures,

had in no degree diminished the devotion with which the sanctuary of Einsiedeln was regarded by Catholic Switzerland.

Not to speak of the more than seventy parishes which annually send their processions thither,

no fewer than two million pilgrims were known to have visited this church between the years of 1820 and 1834.

One pilgrim, who visited the Holy Chapel in 1840 in fulfillment of a vow, has described the throng assembled

there on the great festival in September. The fifty-five inns, which offer accommodation to visitors,

did not suffice to contain one half of those who required a night’s lodging. Looking at the crowds

continually moving between the church and the mountains, everywhere scattered about on the roads and in the streets,

the whole plain,

he says, seemed as if it were covered by a thousand tribes and nations.

There was every imaginable diversity of dress, language, and national physiognomy.

One old couple had come from Alsace, the husband having led his blind wife hither

in hopes that she might obtain the restoration of her sight. During the vespers that preceded the Feast,

the church was so densely packed that it was impossible to make your way through the mass of human beings,

but nevertheless not the slightest disorder prevailed. After vespers the priests entered the confessionals,

and for the remainder of the day and through the long hours of the night not a sound was to be heard but the

continued murmur of prayers from the many pilgrims who kept devout vigil in different parts of the spacious edifice.

At four in the morning the chapel of the Blessed Virgin was brilliantly illuminated,

and Masses began to be celebrated at the different altars, the high Mass being sung at ten by the Apostolic Nuncio;

but by far the most imposing scene was that presented by the grand procession by torchlight which took place

in the evening, when the Blessed Sacrament was carried from the church to a temporary altar erected on the

opposite side of the immense piazza, every portion of the surrounding buildings being lit up, and made as

visible as though it had been broad day. It was truly a marvelous sight to see the immense crowd bowed in adoration,

and this in an age when on every side we were told that faith was dead or dying, that the populace had no longer any

confidence in the power of prayer or the virtue of holy relics, and in fine, to use the common phrase,

that the age of miracles was past.

Those who think so, we would beg to examine the list of miraculous graces obtained before

the statue of Our Lady of Einsiedeln, where they will find the narratives of as many attested miracles

belonging to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as are recorded to have taken place in the tenth.

Of these, remarkable as they are, we shall not say more at present; but miraculous favors are not the only,

or the chief, results which flow from these pilgrimages. Regarded in their most striking aspect they are

great instruments for reviving and reinvigorating the springs of popular devotion – retreats, as it were,

organized on a gigantic scale. On the great annual festivals, the confessors found it no easy task to

satisfy the demands of the vast throngs that invaded their confessionals, and the law was established that

those who came from the greatest distance should be heard first. Just after the Revolution of July, 1830,

this excellent regulation gave rise to a humorous scene in the church. A crowd of German penitents had been

waiting with passive perseverance near one of the confessionals, when the priest perceived some new-comers of

another nation, and addressing his countrymen, My children,

he said, you must retire – here are some

Frenchmen coming.

Blessed Virgin!

exclaimed one of the women, with a lamentable cry, the French are coming!

it is all over with us!

And the good Father had some difficulty in restoring tranquility,

and assuring her that the Frenchmen in question had come, not to burn Our Lady, but to confess their sins.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com