Celebrated Sanctuaries of the Madonna

Fourteenth in a Series

In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries

of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the

wily criticism of many Protestants.

As the writings of Fr. Northcote were much used in our articles on Our Lady of Puy

and Our Lady of La Salette, featured in past issues, we proceed to his chapters

on Our Lady's Sanctuaries in Great Britain:

Anglo-Saxon Sanctuaries

Few countries were richer in Sanctuaries dedicated to the Blessed Virgin than old Catholic England, which,

as many readers are aware, derived its beautiful title of 'The Dowry of Mary' from the number of churches which bore Her name,

of which a large proportion are still standing. Many of these were places of pilgrimage, resorted to no less devoutly than

Einsiedeln or Loreto, whilst the foundations of others is linked with legends which manifest to us how familiar to the mind

of the old English Catholic was the notion that certain spots, and those for the most part 'the solitary places of the

wilderness,' were regarded by Her with special favor, and had not unfrequently been rendered sacred by Her visible presence.

Scattered moreover through the writings of our ancient historians, we find notices of particular favors

granted through the intercession of Our Lady, and sometimes before favorite images or shrines; and these narratives have

a peculiar value, as showing how identical in all ages and countries is the spirit of Catholic devotion, and how wholly

without foundation is that theory which represents the religious practices in use among Catholics of other lands as childish

superstitions, opposed, not merely to Protestant prejudices, but to English good sense. The notion that English people have

a right in virtue of their nationality to be more hard-headed and incredulous than their neighbors, and less susceptible to

devout impressions, is so very generally assumed as indisputable, and made to do such exceedingly bad service in matters of

controversy, that it will not be without its use if we succeed in showing that the Englishman of the seventh, the tenth,

or the thirteenth centuries, though he doubtless displayed many of the characteristic features which we commonly attribute

to his race, had as lively a faith in the supernatural, and as tender a devotion, as the Italian or the Spanish Catholic of

the same date, and that his devotion was expressed after the same simple, and often poetic, fashion as theirs.

To those who believe that devotion to the Mother of God forms an integral part of the Christian system,

the fact that it was preached and practiced in England at a date coeval with the establishment of Christianity does not

require proof. Yet proof might be cited if required, no less from the history of the British than from that of the

Anglo-Saxon Church. Thus William of Malmesbury, in his brief notice of the achievements of King Arthur,

whilst protesting against the fables with which the life of the British hero has been obscured, records as historic

that great victory at Mount Badon – gained, as he says, by the help of the Mother of God, whose image the King bore

into battle. It is likewise said that he had Her image painted inside his shield, and that She many times miraculously

defended him. This shield is declared to have been exposed for public veneration in a church in the British capital,

and is numbered among other miraculous images by the author of the Atlas Marianus, under the title of

Virgo de Clypeo, or Our Lady of the Shield.

The most ancient Christian temple ever erected in this island is held by constant and venerable tradition to have been that

little church of wreathed twigs which St. Joseph of Arimathea is said to have constructed at Glastonbury, and which,

according to ancient legends, was believed to have been consecrated by Our Lord Himself, in honor of His Blessed Mother.

Whoever may have been the founder of this church, it was certainly dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, and is described in 433,

as 'an ancient and holy spot, chosen and sanctified by God in honor of the Immaculate Mother of God,

the Most Blessed Virgin Mary.' The stone church subsequently built, appears to have been dedicated to Ss. Peter and Paul;

but, in 530, St. David, visiting Glastonbury, with seven of his suffragan bishops, just after the close of his celebrated

'Synod of Victory,' added a chapel to the east end of the church, which he consecrated to the Blessed Virgin,

and adorned the altar with a precious sapphire. It was called 'The Great Sapphire of Glastonbury,' and was fixed in a

golden super-altar, together with which it was delivered up into the rapacious hands of Henry VIII, at the time of the

suppression. Henceforward, the whole church was commonly spoken of as the church of the Blessed Virgin;

and, in 708, Ina, King of the West Saxons, in gratitude for the prosperity of his reign, which he attributed to the

special patronage of Our Lady, rebuilt both church and monastery on a grand scale, and endowed the new edifice with

a profusion of costly treasures. The Church, thus restored, was dedicated to Our Lady, Saint Peter, and St. Paul;

but in Ina’s charter it is constantly spoken of as 'Saint Mary of Glastonbury,' and the same document makes mention of

'the many and unheard-of miracles' which had already illustrated this holy spot (image of the ruins of the Lady Chapel

above left).

The most ancient Christian temple ever erected in this island is held by constant and venerable tradition to have been that

little church of wreathed twigs which St. Joseph of Arimathea is said to have constructed at Glastonbury, and which,

according to ancient legends, was believed to have been consecrated by Our Lord Himself, in honor of His Blessed Mother.

Whoever may have been the founder of this church, it was certainly dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, and is described in 433,

as 'an ancient and holy spot, chosen and sanctified by God in honor of the Immaculate Mother of God,

the Most Blessed Virgin Mary.' The stone church subsequently built, appears to have been dedicated to Ss. Peter and Paul;

but, in 530, St. David, visiting Glastonbury, with seven of his suffragan bishops, just after the close of his celebrated

'Synod of Victory,' added a chapel to the east end of the church, which he consecrated to the Blessed Virgin,

and adorned the altar with a precious sapphire. It was called 'The Great Sapphire of Glastonbury,' and was fixed in a

golden super-altar, together with which it was delivered up into the rapacious hands of Henry VIII, at the time of the

suppression. Henceforward, the whole church was commonly spoken of as the church of the Blessed Virgin;

and, in 708, Ina, King of the West Saxons, in gratitude for the prosperity of his reign, which he attributed to the

special patronage of Our Lady, rebuilt both church and monastery on a grand scale, and endowed the new edifice with

a profusion of costly treasures. The Church, thus restored, was dedicated to Our Lady, Saint Peter, and St. Paul;

but in Ina’s charter it is constantly spoken of as 'Saint Mary of Glastonbury,' and the same document makes mention of

'the many and unheard-of miracles' which had already illustrated this holy spot (image of the ruins of the Lady Chapel

above left).

The catalogue of Ina's donations deserves insertion, as an example of royal munificence in the ages of Faith,

and will bear comparison with any similar records of offerings made at the shrines of Montserrat or Loreto.

In the first place, the chapel of St. Joseph, which he attached to the church, was entirely plated over with precious metals,

and on it he is said to have expended 2640 pounds of silver and 264 pounds of gold for the altar alone;

besides which he presented a gold chalice; a paten, weighing ten pounds; a gold thurible, weighing eight pounds;

two silver candlesticks, of twelve pounds and a half; a gold cover for the Book of Gospels, of twenty pounds;

a holy water pot, of twenty pounds in silver; images of Our Lord, the Blessed Virgin and the Twelve Apostles,

containing 172 pounds of silver, and twenty-eight pounds of gold; and lastly, a pall for the altar, and other instruments,

all of cloth of gold, curiously wrought, and adorned with precious stones.

We find from a very profane letter addressed by Layton to Cromwell, that among the relics preserved at

Glastonbury, and sacrilegiously seized by the visitors of Henry VIII, were a portion of Our Lady's girdle,

and one of Her robes, as well as the girdle of St. Mary Magdalene, which last was presented by the Empress Mechtilde.

Our Lady's girdle is described as 'of red silk, a solemn relic, sent to women in travail.' There was also preserved a

relic of the Holy Coat (of Christ).

During the period of the Danish incursions, the church so magnificently endowed by Ina and his Queen fell

into partial decay, though it never ceased to be regarded with singular veneration, both by the British and Anglo-Saxon race.

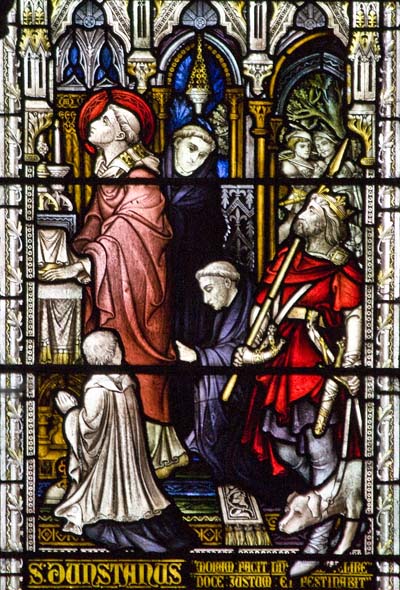

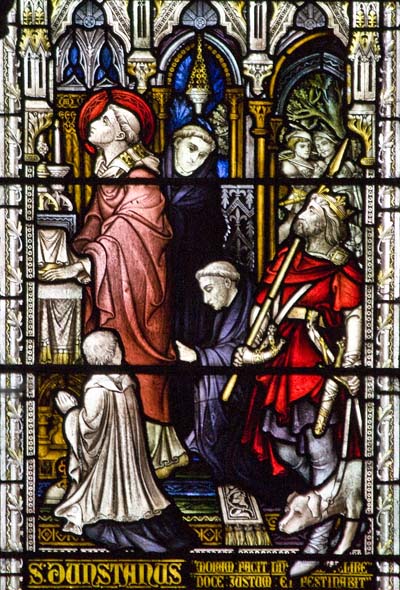

Its restoration was effected by St. Dunstan, and familiar as we are with some of the legends of his life at Glastonbury,

there are others connected with his special devotion to the Mother of God, and with the popular devotion paid to Her in

this Sanctuary, which are less commonly quoted, and are very much to our present purpose.

We read then that, as has so often been the case with other great servants of God, destined to achieve

some special work in the Church, a miraculous sign was granted to his mother Kyndreda, before his birth, which seemed

to foreshadow the future greatness of her child. On the Feast of the Purification, she and her husband, Herstan,

were attending the solemn Mass of the Feast in the church of Our Lady, and according to custom they, in common with

the rest of those present, held the burning tapers which they were afterwards to offer at the altar. Suddenly every

taper was extinguished, and as the people looked about to discover the cause of so strange an accident, they beheld

the candle which Kyndreda bore suddenly relighted by a flame which descended, as it seemed, from Heaven.

Hastening to her they all relit their tapers from the one she held, and regarded the incident as betokening some

special grace which should be granted to her child, who they supposed would certainly prove to be a favored client

of Our Lady.

It was in this same church that St. Dunstan received his early education, imbibing, as was natural, a special devotion to

the Blessed Virgin; and it was here also that he returned after a brief time spent at the court of King Athelstan,

and led an eremitical life in a cell which he had constructed for himself. Osbern, a monk of Canterbury,

who wrote his life about the year 1020, informs us that among other persons attracted to Glastonbury by the fame of

his sanctity, was a certain lady of the blood-royal named Ethelsgiva, or Ethelfleda, who was so charmed by his instructions

that she caused a small habitation to be built for her adjoining Our Lady's Church, wherein she spent the remainder of her days,

frequenting the church both by day and night, and spending her time in the exercise of prayer, alms-deeds, and penance.

Ethelsgiva shared the devotion of her spiritual father towards Our Lady of Glastonbury, and abundantly provided means

for keeping up the service of God in her favorite Sanctuary. And, in return, Our Lady bestowed many favors upon her,

so that she was said to obtain whatever she asked in prayer. One example of a homely description is thus agreeably

related by Osbern:

It was in this same church that St. Dunstan received his early education, imbibing, as was natural, a special devotion to

the Blessed Virgin; and it was here also that he returned after a brief time spent at the court of King Athelstan,

and led an eremitical life in a cell which he had constructed for himself. Osbern, a monk of Canterbury,

who wrote his life about the year 1020, informs us that among other persons attracted to Glastonbury by the fame of

his sanctity, was a certain lady of the blood-royal named Ethelsgiva, or Ethelfleda, who was so charmed by his instructions

that she caused a small habitation to be built for her adjoining Our Lady's Church, wherein she spent the remainder of her days,

frequenting the church both by day and night, and spending her time in the exercise of prayer, alms-deeds, and penance.

Ethelsgiva shared the devotion of her spiritual father towards Our Lady of Glastonbury, and abundantly provided means

for keeping up the service of God in her favorite Sanctuary. And, in return, Our Lady bestowed many favors upon her,

so that she was said to obtain whatever she asked in prayer. One example of a homely description is thus agreeably

related by Osbern: On a certain day King Athelstan coming to Glastonbury, went to visit St. Mary's Church,

on account of the sanctity of the place. Ethelsgiva hearing this, besought him to rest awhile in her house,

and to accept refreshment in the form of food and drink. The King somewhat unwillingly consented, not wishing to offend

one related to him by family ties, and whom, moreover, he knew to be so devout a servant of God. Delighted at this

she set herself to prepare what was required for the royal visit, and at last satisfied herself that a sufficient

supply of everything had been provided, except a certain drink call mead (honey wine), to the use of which the

English are greatly addicted, and of which she had but little. Fearing, therefore, lest the deficiency of this should

cast into the shade the plentiful supply of all the rest, she betook herself to the chapel of Our Lady, in order to ask

Her help in this emergency. Prostrating there alone, she begged her good Mother to obtain from God, by Her prayers and

blessings, that the mead be abundantly increased. Wonderful to say, the King with a great multitude of his followers

sat down to table, and all of them drank copiously of the aforesaid liquor, yet the vessel out of which it was drawn

always remained full. And when the King at last departed, it hardly seemed as if anything had been taken out.

This devout lady afterwards left all her wealth for the endowment of Glastonbury, and for other monasteries.

Few of our English Saints can be cited, the character of whose sanctity is so strictly contemplative as

that of St. Dunstan, or of whom there are recorded a greater number of visions, ecstasies, and heavenly favors.

One of these narratives shows us the devout client of Mary watching at night in one of Her sanctuaries,

and rewarded for his devotion by Her visible presence. For, even when filling the Archepiscopal throne,

St. Dunstan abandoned none of his austere eremitical exercises, but spent a great part of his nights in prayer and vigil.

When he lived at Canterbury,

says his biographer, it was his custom to visit the holy places by night,

and there to offer himself to God by repeated acts of contrition and compunction.

On a certain time, according to his custom, he thus in the silence of the night visited the Church of

St. Peter and St. Paul, where the Blessed Augustine and other fathers of the church of Canterbury lie buried,

and there for a long time lay prostrate in prayer. Then, going forth, he made his way to the chapel of the

Blessed Mary ever Virgin, which was situated in the east part of the monastery. (Eadmer, in his minute account of the

ancient cathedral as it existed before the time of Lanfranc distinctly says that the Lady Chapel was at the west end of

the church. But it must be remembered that the building which he describes was not the same which was standing in

St. Dunstan's time. That had been burnt down by the Danes in 1011, and after being rebuilt by St. Canute in 1017,

was again destroyed by fire in 1067. Eadmer's description appears to apply to the cathedral built by St. Canute.)

As he drew near, he heard voices inside chanting the words, Gaudent in cœlis animæ sanctorum qui Christi vestigia sunt

secuti (Let the souls of the Saints in Heaven rejoice, who followed in the footsteps of Christ.) Astonished at this,

he stood at the door, and looking through the chinks (for it was locked), he beheld the chapel full of light and a

number of persons sitting clothed in white, who seemed to be singing this anthem.

At another time, when he repaired by night, for a similar purpose, to the Church of Our Lady, he beheld that

Blessed Virgin of Virgins, surrounded by a choir of virgins, coming to meet him. She conducted him with great

honor into Her Sanctuary, two of the attendant choir going before and singing a hymn, each verse of which was

repeated by the whole choir until the man of God had entered the Church.

At another time, when he repaired by night, for a similar purpose, to the Church of Our Lady, he beheld that

Blessed Virgin of Virgins, surrounded by a choir of virgins, coming to meet him. She conducted him with great

honor into Her Sanctuary, two of the attendant choir going before and singing a hymn, each verse of which was

repeated by the whole choir until the man of God had entered the Church.

The Lady Chapel, which was the scene of these heavenly visions, no longer exists at Canterbury.

Nevertheless, as we shall hereafter see, another notable Sanctuary of the Blessed Virgin was raised in after-ages

in the very crypt where reposed the ashes of St. Dunstan. The devotion borne by him towards the Mother of God probably

had its influence over the Anglo-Saxon princes whose counsels he directed, and who are all spoken of by their historians

as special clients of Mary. Thus Edgar the Peaceable (image left) laid his scepter on the altar of

Our Lady of Glastonbury, and solemnly placed his kingdom under Her patronage; and we find St. Edward the Martyr

uniting his authority with that of the Archbishop in a formal authorization of the popular pilgrimage to one of

Our Lady's Sanctuaries. Sideman, Bishop of Crediton in Devonshire, having died in 977, whilst the great Council

of Kirtlington was still sitting, the King and Archbishop decided that he should be buried in St. Mary's Minster at Abingdon,

which had recently been restored by St. Ethelwold. Thither his remains were accordingly conveyed, and it was at the

same time ordained by the council that 'it should be lawful for the country people to make religious pilgrimage to the

church of St. Mary of Abingdon.'

About the same time that Ina was restoring the church of Glastonbury, the Sanctuaries of Evesham, Tewkesbury,

and Worcester were rising on the banks of the Severn; all destined to become the resort of English pilgrims,

while the first-named of the three is said to trace its foundation to a miraculous apparition precisely similar

in character to those numerous legends of later date which are to be found attached to the history of so many of

Our Lady's Sanctuaries. Towards the end of the 7th century, the valley which now by its rich cultivation bears the

title of the Garden of England, was a desert place overgrown with thorns and briars, which Egwin, third Bishop of Worcester,

asked and obtained as a grant from Ethelred, King of Mercia, as a place of pasture for the swine belonging to his monastery.

The swine were tended by four swineherds, one of whom, named Eoves, happened on a certain day to penetrate

into the thicket, and beheld a Lady standing on a particular spot with two other virgins, one on either side, all of them

of exceeding beauty, and shining with a light surpassing that of the sun. The Lady held a book in Her hand,

and was chanting most exquisite psalmody with Her companions. The poor swineherd, dazzled by the splendor of the vision,

returned home terrified and trembling, and related all he had seen to the Bishop. And he, maturely considering the matter,

after prayer and fasting, took with him three companions, and singing psalms and devout prayers, proceeded barefoot to the

valley. When they had reached the thicket, Egwin, leaving his companions, proceeded alone to the spot indicated,

and prostrating on the ground, remained there a long time imploring the Divine mercy. When he rose from prayer,

he beheld the three virgins shining gloriously as they had previously appeared to Eoves. But She who stood in the

midst far outshone Her companions, and seemed to him whiter than the lily, more brilliant than the rose,

and fragrant with an indescribable odor; and he perceived that She held in Her hands a book and a golden cross,

which likewise shone with a brilliant light. As he was considering within himself that this could be no other than the

Blessed Mother of God, She, as if to answer him that his judgment was correct, stretched out Her hand and blessed him

with the cross which She extended towards him, and thereupon the vision disappeared.

Egwin, who felt his heart filled with extraordinary consolation, understood that it was the will of God

that he should erect a church in that place, and dedicate it to the Ever-Blessed Virgin. For in the early part of his

episcopate, when vexed by many temptations and persecutions on the part of his flock, whose heathenish practices he had

courageously opposed, he had vowed to build some temple to the Lord should He be pleased to deliver him from his trials.

He therefore caused the place to be cleared, and began the work, which was completed in the year 701,

through the assistance of Offa, King of the East Angles, and the two Mercian Kings, Ethelred and Coenred.

In the charter granted by Coenred and Offa in 709, they solemnly confirm the gift of 'that place wherein

the Blessed Virgin Mary manifested Herself to the venerable man Egwin;' and another charter, granted by Egwin himself in 714,

which also bears the signatures of the Kings, gives a circumstantial account of the events already narrated.

The story of the first foundation of Evesham was moreover depicted on the Abbey seal, the principal side of which

represented the abbey upheld by the kneeling figure of St. Egwin, while on the other appeared the three virgins of his vision.

Below, in a kind of trefoil, we see Eoves tending his swine in the forest, surrounded by the following old English legend:

Eoves - her - wenede - mit - was - swin

Ecgwin - clepet - Vis - Eovishom

– which may be thus rendered: 'Eoves here wended with his swine, Egwin named it Vis (or Vic) Eoveshom,'

that is, Evesham of the Wicci, as the people of Worcestershire were then denominated.

Evesham in after times became a favorite place of pilgrimage, and possessed more than one image of Our Lady, all of which,

as the monk of Evesham informs us, were regarded by the people with great veneration.

Evesham in after times became a favorite place of pilgrimage, and possessed more than one image of Our Lady, all of which,

as the monk of Evesham informs us, were regarded by the people with great veneration. Truly,

he says, there were

in this same church three or four images of our Blessed Saint Mary, having in Her lap the image of Our Savior Jesus Christ

in the form of a little babe; and they were set at every altar, right well painted, and fair arrayed with gold and divers

other colors, the which showed to the people that beheld them great devotion. And before every image hung a lamp, the which,

after the custom of this same church, were wont to be lighted at every principal feast through all the year, both by night

and by day, enduring from the first vespers until the second vespers, before the aforesaid images of our Blessed Saint Mary

(restored image of Our Lady of Evesham at right).

Almost equally celebrated was the Church of Our Lady of Tewkesbury, founded in 715 by the two Mercian dukes

Oddo and Dodo. Willima of Malmesbury asserts that the name of the spot was a corruption of the word Theotocosbiria,

or the Curia Dei Genitricis (Court of the Mother of God), but by others it is said to have been derived from a certain

hermit called Theokus, who had his residence on the banks of the river Severn. This Church possessed an image of Our Lady

which had the singular good fortune to escape destruction at the time of the 'Reformation,' owing, as it would seem,

to the reluctance of the magistrates to rouse the indignation of the populace, who regarded it with extraordinary veneration.

At last, however, in the reign of James I, the Puritan 'zeal' of a certain inhabitant of the town could no longer endure

the presence of this relic of the old religion, and he petitioned the magistrates to deliver it over into his hands.

Having at last gained possession of it, in order to show more marked contempt for the holy image, he caused it to be

hollowed out, and used it as a drinking-trough for his swine. But it was remarked that all the swine that drank out

of it perished by disease, and that the children of him who committed this sacrilege became every one of them lame,

blind, or otherwise deformed. The old stone trough, which had been replaced by the profaned image, was fixed by the

side of a well, for the purpose of preventing those who went thither to draw water from losing their footing.

But the unhappy man on a time chancing to pass by that way, leapt over this very stone unawares, and falling into the well,

was miserably drowned. This occurred about the year 1625, and was communicated in a private letter from England to

Father William Gumppenberg, of the Society of Jesus, by whom they were inserted in his work entitled Atlas Marianus.

Another Sanctuary of Anglo-Saxon foundation was that of Coventry, where good Earl Leofric and his wife Godiva

founded the Benedictine Monastery of St. Mary's, in the year 1043. This Church was remarkable above all others in England

for the extraordinary riches it contained. Godiva bestowed all her treasure upon it, and sending for skillful goldsmiths

she caused them to make an abundance of crosses, images, and other wonderful ornaments for the decoration of the Church.

William of Malmesbury says that it was so enriched with gold and silver that the walls seemed too narrow to contain it all,

and that the eyes of the spectators were dazzled as though what they looked on had not been a thing of real life,

but a sort of miracle. The very beams supporting the shrine were overlaid with precious metals; and in the time of

William Rufus (son of William the Conqueror), Robert de Limesay, Bishop of Chester, who had been induced to

transfer his see from Chester to Coventry, on account of the riches laid up in the latter place, ruthlessly scraped off

one beam as much silver as was valued at 500 marks.

But the richest as well as the most celebrated ornament of this Church was the chaplet of gems which Godiva,

when lying on her death-bed, desired to be hung around the neck of Our Lady's image, and which was valued at 100 marks

of silver (each mark was 8.25 ounces). The gems were strung on a thread and used after the fashion of a rosary,

for Godiva, 'beginning at the first, was used as she touched each gem to say special prayers, and so proceeding from gem

to gem, there was no chance of neglecting the number of prayers she desired to repeat.' She requested, moreover,

that whosoever visited the church out of devotion should say as many prayers as there were gems on her chaplet.

This practice of repeating a certain number of Paters and Aves on a string of beads was of very old date

among the Anglo-Saxons; and the Benedictine writers who claim for St. Benedict the honor of being the first to introduce

the use of Our Ladys Psalter, as it was called, are used to represent it as chiefly propagated in the 8th century by

St. Bede the Venerable. Fr. Gabriel Bucelin, in his Chronologia Benedictino Mariana,

declares that the spread of this devotion in England was attended with very extraordinary results, and that many victories

were gained over the Danes by its means. He adds, moreover, that the English who fled from their own land to escape the

violence of the Danes carried their favorite devotion with them, and became the instrument of propagating it in other

countries where it had fallen into decay. Bd. Alan de la Roche (image left), the great Dominican preacher of the

holy Rosary in the 15th century, admits the Benedictine claims, and especially notices the fact that most of the ancient

images of the Blessed Virgin in England, were represented holding the beads in their hands. (It was specifically

the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary which Our Lady revealed to St. Dominic.) We may add that in after times a

great number had the beads suspended around their necks, and that Godiva's was only one among many similar bequests

made by pious ladies.

This practice of repeating a certain number of Paters and Aves on a string of beads was of very old date

among the Anglo-Saxons; and the Benedictine writers who claim for St. Benedict the honor of being the first to introduce

the use of Our Ladys Psalter, as it was called, are used to represent it as chiefly propagated in the 8th century by

St. Bede the Venerable. Fr. Gabriel Bucelin, in his Chronologia Benedictino Mariana,

declares that the spread of this devotion in England was attended with very extraordinary results, and that many victories

were gained over the Danes by its means. He adds, moreover, that the English who fled from their own land to escape the

violence of the Danes carried their favorite devotion with them, and became the instrument of propagating it in other

countries where it had fallen into decay. Bd. Alan de la Roche (image left), the great Dominican preacher of the

holy Rosary in the 15th century, admits the Benedictine claims, and especially notices the fact that most of the ancient

images of the Blessed Virgin in England, were represented holding the beads in their hands. (It was specifically

the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary which Our Lady revealed to St. Dominic.) We may add that in after times a

great number had the beads suspended around their necks, and that Godiva's was only one among many similar bequests

made by pious ladies.

In the troublesome times of King Stephen, Robert Marmion, Lord of Tamworth, seized the monastery of St. Mary's,

and turning out the monks, converted the Church into a fortification which he held against the Earl of Chester.

Roger de Hovedon and Henry of Huntingdon tell us that, as if to mark the Divine anger at this sacrilege,

blood was seen by many persons to bubble out of the pavement, both in the Church and the adjoining cloister.

And the former historian adds that he had inspected the marks with his own eyes. But whatever may be thought of the truth

of this prodigy, the judgment of Heaven was not long in overtaking the sacrilegious oppressor. For as he one day made a

sally against the enemy, he fell into one of the trenches he had himself caused to be dug, and was wounded in the foot

by an arrow. He made light of the injury, which appeared but a trifle; nevertheless, it speedily caused his death before

the sentence of excommunication was removed which he had incurred by his crimes.

Leofric and Godiva lie buried in the two porches of their church. Besides their benefactions to this monastery,

they bestowed large endowments on other churches, and specially on the three famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady at Evesham,

Worcester, and Stow, the latter of which was the mother house of Eynsham Abbey, near Oxford. A story is told in the

early chronicles of the latter abbey, which is sufficiently connected with the subject to find a place here.

In the reign of Henry the First, there was a certain monk of Eynsham who had a special devotion to the Blessed Virgin,

and had received many favors from Her. He happened to be present at the death-bed of one of the young scholars brought up

in the abbey, and beheld him surrounded by demons endeavoring to disturb him with their temptations. The bystanders

sprinkled him with holy water from time to time, but the evil spirits still continued to vex him, until the monk invoking

the aid of Our Lady, She appeared and drove away the demons by Her presence. And it was manifest that She was seen not only

by Her devout votary, but also by the sick boy himself, who endeavored to mark his gratitude by singing the responsory,

Gaude Maria Virgo. His memory failed him in the middle of the verse, but the monk made him repeat after him,

and at the concluding words he tranquilly breathed his last.

Many of the parish churches of London were dedicated to Our Lady in Saxon times, and the devotion of the

citizens towards the Mother of God is specially noticed by the historian, Florence of Worcester. In particular,

it was manifested at the time when the city was threatened by Anlaf, King of Norway, and Sweyn, King of Denmark,

who, in 994, sailed up the Thames in 94 vessels, each vessel furnished with three benches of oars. With this force,

they attacked the city and set it on fire in several places. It was the Feast of Our Lady's Nativity,

a day observed as a high festival. And it appears that the chief assault was made whilst the Londoners were in church

invoking the aid of the Queen of Heaven against the horde of barbarians 'whose hands were red with the blood of priests,

and begrimed with the spoil of churches.' Although taken by surprise they were not disheartened or panic-struck,

but hurrying from the churches to the walls they succeeded in repelling the enemy, and that in so marvelous a way,

and with so little resistance on the part of the pagans, that they hesitated not to ascribe their victory to the

special assistance of the Blessed Virgin.

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

The most ancient Christian temple ever erected in this island is held by constant and venerable tradition to have been that

little church of wreathed twigs which St. Joseph of Arimathea is said to have constructed at Glastonbury, and which,

according to ancient legends, was believed to have been consecrated by Our Lord Himself, in honor of His Blessed Mother.

Whoever may have been the founder of this church, it was certainly dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, and is described in 433,

as 'an ancient and holy spot, chosen and sanctified by God in honor of the Immaculate Mother of God,

the Most Blessed Virgin Mary.' The stone church subsequently built, appears to have been dedicated to Ss. Peter and Paul;

but, in 530, St. David, visiting Glastonbury, with seven of his suffragan bishops, just after the close of his celebrated

'Synod of Victory,' added a chapel to the east end of the church, which he consecrated to the Blessed Virgin,

and adorned the altar with a precious sapphire. It was called 'The Great Sapphire of Glastonbury,' and was fixed in a

golden super-altar, together with which it was delivered up into the rapacious hands of Henry VIII, at the time of the

suppression. Henceforward, the whole church was commonly spoken of as the church of the Blessed Virgin;

and, in 708, Ina, King of the West Saxons, in gratitude for the prosperity of his reign, which he attributed to the

special patronage of Our Lady, rebuilt both church and monastery on a grand scale, and endowed the new edifice with

a profusion of costly treasures. The Church, thus restored, was dedicated to Our Lady, Saint Peter, and St. Paul;

but in Ina’s charter it is constantly spoken of as 'Saint Mary of Glastonbury,' and the same document makes mention of

'the many and unheard-of miracles' which had already illustrated this holy spot (image of the ruins of the Lady Chapel

above left).

The most ancient Christian temple ever erected in this island is held by constant and venerable tradition to have been that

little church of wreathed twigs which St. Joseph of Arimathea is said to have constructed at Glastonbury, and which,

according to ancient legends, was believed to have been consecrated by Our Lord Himself, in honor of His Blessed Mother.

Whoever may have been the founder of this church, it was certainly dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, and is described in 433,

as 'an ancient and holy spot, chosen and sanctified by God in honor of the Immaculate Mother of God,

the Most Blessed Virgin Mary.' The stone church subsequently built, appears to have been dedicated to Ss. Peter and Paul;

but, in 530, St. David, visiting Glastonbury, with seven of his suffragan bishops, just after the close of his celebrated

'Synod of Victory,' added a chapel to the east end of the church, which he consecrated to the Blessed Virgin,

and adorned the altar with a precious sapphire. It was called 'The Great Sapphire of Glastonbury,' and was fixed in a

golden super-altar, together with which it was delivered up into the rapacious hands of Henry VIII, at the time of the

suppression. Henceforward, the whole church was commonly spoken of as the church of the Blessed Virgin;

and, in 708, Ina, King of the West Saxons, in gratitude for the prosperity of his reign, which he attributed to the

special patronage of Our Lady, rebuilt both church and monastery on a grand scale, and endowed the new edifice with

a profusion of costly treasures. The Church, thus restored, was dedicated to Our Lady, Saint Peter, and St. Paul;

but in Ina’s charter it is constantly spoken of as 'Saint Mary of Glastonbury,' and the same document makes mention of

'the many and unheard-of miracles' which had already illustrated this holy spot (image of the ruins of the Lady Chapel

above left). It was in this same church that St. Dunstan received his early education, imbibing, as was natural, a special devotion to

the Blessed Virgin; and it was here also that he returned after a brief time spent at the court of King Athelstan,

and led an eremitical life in a cell which he had constructed for himself. Osbern, a monk of Canterbury,

who wrote his life about the year 1020, informs us that among other persons attracted to Glastonbury by the fame of

his sanctity, was a certain lady of the blood-royal named Ethelsgiva, or Ethelfleda, who was so charmed by his instructions

that she caused a small habitation to be built for her adjoining Our Lady's Church, wherein she spent the remainder of her days,

frequenting the church both by day and night, and spending her time in the exercise of prayer, alms-deeds, and penance.

Ethelsgiva shared the devotion of her spiritual father towards Our Lady of Glastonbury, and abundantly provided means

for keeping up the service of God in her favorite Sanctuary. And, in return, Our Lady bestowed many favors upon her,

so that she was said to obtain whatever she asked in prayer. One example of a homely description is thus agreeably

related by Osbern:

It was in this same church that St. Dunstan received his early education, imbibing, as was natural, a special devotion to

the Blessed Virgin; and it was here also that he returned after a brief time spent at the court of King Athelstan,

and led an eremitical life in a cell which he had constructed for himself. Osbern, a monk of Canterbury,

who wrote his life about the year 1020, informs us that among other persons attracted to Glastonbury by the fame of

his sanctity, was a certain lady of the blood-royal named Ethelsgiva, or Ethelfleda, who was so charmed by his instructions

that she caused a small habitation to be built for her adjoining Our Lady's Church, wherein she spent the remainder of her days,

frequenting the church both by day and night, and spending her time in the exercise of prayer, alms-deeds, and penance.

Ethelsgiva shared the devotion of her spiritual father towards Our Lady of Glastonbury, and abundantly provided means

for keeping up the service of God in her favorite Sanctuary. And, in return, Our Lady bestowed many favors upon her,

so that she was said to obtain whatever she asked in prayer. One example of a homely description is thus agreeably

related by Osbern:  At another time, when he repaired by night, for a similar purpose, to the Church of Our Lady, he beheld that

Blessed Virgin of Virgins, surrounded by a choir of virgins, coming to meet him. She conducted him with great

honor into Her Sanctuary, two of the attendant choir going before and singing a hymn, each verse of which was

repeated by the whole choir until the man of God had entered the Church.

At another time, when he repaired by night, for a similar purpose, to the Church of Our Lady, he beheld that

Blessed Virgin of Virgins, surrounded by a choir of virgins, coming to meet him. She conducted him with great

honor into Her Sanctuary, two of the attendant choir going before and singing a hymn, each verse of which was

repeated by the whole choir until the man of God had entered the Church. Evesham in after times became a favorite place of pilgrimage, and possessed more than one image of Our Lady, all of which,

as the monk of Evesham informs us, were regarded by the people with great veneration.

Evesham in after times became a favorite place of pilgrimage, and possessed more than one image of Our Lady, all of which,

as the monk of Evesham informs us, were regarded by the people with great veneration.  This practice of repeating a certain number of Paters and Aves on a string of beads was of very old date

among the Anglo-Saxons; and the Benedictine writers who claim for St. Benedict the honor of being the first to introduce

the use of Our Ladys Psalter, as it was called, are used to represent it as chiefly propagated in the 8th century by

This practice of repeating a certain number of Paters and Aves on a string of beads was of very old date

among the Anglo-Saxons; and the Benedictine writers who claim for St. Benedict the honor of being the first to introduce

the use of Our Ladys Psalter, as it was called, are used to represent it as chiefly propagated in the 8th century by