In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

The last chapter gave us examples of sanctuaries to which a certain miraculous character was attributed in Anglo-Saxon times, and towards which the popular devotion manifested itself in the form of frequent pilgrimages and munificent votive offerings. We will now see that the national spirit underwent no change in this respect after the Norman Conquest, and whilst the older sanctuaries lost none of their popularity, a great number of new ones trace their origin to the Norman lords and prelates of the twelfth century.

Present in the army of William the Conqueror, at the battle of Hastings (1066), was one prelate who attained considerable celebrity in the chronicles of his own time, as the founder of the Cathedral of Coutances in Normandy, a sanctuary which, though not of English origin, must be briefly noticed in this place, because the extraordinary graces of which it became the scene almost immediately on its construction were in a certain way connected with circumstances which belong to the history of England. Geoffrey de Montbrary, Bishop of Coutances, is said to have been the first to introduce into Normandy the ogival or pointed style of architecture, and his cathedral, which owed no small part of its decorations to the skill of English artists, was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin in the year 1056. Very soon after the conquest of England by Duke William, however, an event occurred which determined Geoffrey to enlarge his cathedral by the addition of a new chapel, and to establish within its walls the celebration of a new Feast. The event referred to, was none other than the celebrated vision of Helsinus, Abbot of Ramsay, who being sent by William in 1070 as an ambassador to the Danish court, and overtaken by a terrible tempest, commended himself in his distress to God and Our Lady, and thereupon perceived the figure of a venerable man walking on the troubled waves, who promised that he and his companions should reach their port in safety, on condition that the abbot would engage on his return to England, to keep the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin on the 8th of December, every year, and to procure the celebration of the same by others, so far as lay in his power.

Helsinus gladly made the required promise, and faithfully fulfilled it. Not only did he, on his arrival in England, introduce the Feast into his own Abbey of Ramsay, but he traveled through the country, preaching the devotion to rich and poor, and afterwards passed over for the same purpose into Normandy, where his words were received with enthusiasm. All the Norman bishops assembled in synod, resolved to establish the celebration of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception throughout the entire province, whence the Feast was commonly known in France as the Fête aux Normands. Thirty years later, St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, induced the English bishops to follow the example set them by the prelates of Normandy, and the devotion soon spread into other countries. It gave rise to various confraternities and pious foundations, but no one showed more active zeal in its propagation than Geoffrey de Montbray, who dedicated a large chapel attached to his cathedral, in honor of this mystery.

An image of the Blessed Virgin placed in the chapel became at once the object of great popular veneration, and so extraordinary were the miracles worked before it that Geoffrey thought it prudent to consign them to writing, and appointed one of his canons to draw up an authentic narrative of the events which every day took place before their eyes. This compilation from the color of its binding was called the Black Book, and the author solemnly attests that nothing is herein set down, of which he and other members of the Chapter have not themselves been witnesses.

The vision of Helsinus has so often been treated as a mere legendary tale, while at the same time it has so

peculiar an interest to English Catholics, that it is satisfactory to find its truth confirmed by the authentic history

of the Coutances foundation, avowedly undertaken in consequence of the devotion towards Our Lady's Immaculate Conception

which had followed on the preaching of Helsinus; and we may here take occasion to add the narrative of another deliverance

at sea which also led to the erection of a sanctuary of Our Lady, on the shores of Normandy. The votary in the present

instance was none other than the Empress Matilda, granddaughter of the Conqueror, who during the bloody civil war carried

on between her adherents and those of Stephen de Blois, being forced in the year 1145 to fly from England and take refuge

in Normandy, was assailed in the Channel by a storm which threatened to sink her vessel. Whilst the sailors and others

on board gave themselves up for lost, the Empress alone showed no signs of fear.

The vision of Helsinus has so often been treated as a mere legendary tale, while at the same time it has so

peculiar an interest to English Catholics, that it is satisfactory to find its truth confirmed by the authentic history

of the Coutances foundation, avowedly undertaken in consequence of the devotion towards Our Lady's Immaculate Conception

which had followed on the preaching of Helsinus; and we may here take occasion to add the narrative of another deliverance

at sea which also led to the erection of a sanctuary of Our Lady, on the shores of Normandy. The votary in the present

instance was none other than the Empress Matilda, granddaughter of the Conqueror, who during the bloody civil war carried

on between her adherents and those of Stephen de Blois, being forced in the year 1145 to fly from England and take refuge

in Normandy, was assailed in the Channel by a storm which threatened to sink her vessel. Whilst the sailors and others

on board gave themselves up for lost, the Empress alone showed no signs of fear. Have courage,

she said,

Our Lady is all-powerful, and if we have recourse to Her, She will not fail to come to our aid. I make a vow,

if we reach land in safety, to build a chapel in Her honor on whatever spot we first set foot, and to sing a hymn to

Our Lady of Good Succor as soon as we shall come in sight of land.

No sooner had she pronounced her vow,

than the storm seemed to abate, and the wind changing in their favor, they were not long in reaching the coast of Normandy.

The pilot, who was on look-out at the mast-head, observing the land, cried out impatiently, Cante, Reyn! vechi terre!

(Sing, Queen, here is the land!)

and the princess immediately intoned her hymn, in which the knights and sailors

vociferously joined. They cast anchor in the little bay of Equeurdreville in Lower Normandy, and landing at Cherbourg,

the first care of the Empress was to mark out the site of a chapel, of which she herself laid the first stone,

and which was finished by her son, King Henry II. It bore the title of Our Lady of the Vow, and was still standing in 1793,

when it was demolished by the revolutionary government of France, in order to enlarge the port of Cherbourg.

Since then, however, a new and magnificent church has been raised, which though not reared on the same site,

bears the same title of Our Lady of the Vow, and so thoroughly does the old tradition still survive in the

hearts of the people, that among the decorations of this church erected in the nineteenth century, are to be

seen a picture and a banner, both representing our English princess in the midst of the tempest, and in the act

of pronouncing her vow.

We must, however, hasten to speak of some of the sanctuaries actually erected at this time on the English soil, or the celebrity of which appears to have increased in any considerable degree at this period. It will be remembered that many of the Norman Prelates who were placed in possession of the English Sees by the Conqueror were remarkable as architects, and a very large number of the English cathedrals and parish churches were rebuilt by them with great increase of splendor.

A synod held in London, in 1075, and presided over by Archbishop Lanfranc, provided moreover for the removal

of Sees from small villages and defenseless towns to places of greater importance in the diocese, and it was thus that the

See of Dorchester, near Oxford, became removed to Lincoln, where Bishop Remigius, a follower of the Conqueror,

erected a magnificent cathedral which he purposed dedicating to the Blessed Virgin, though he died on the day

before the ceremony took place. We find Our Lady of Lincoln frequently mentioned among the sanctuaries which

were regarded by the English with special veneration. The inhabitants of Lincoln who took part with King Stephen

in the civil war, choosing Her as their particular Patroness, attributed to Her intercession the great victory

which they gained in 1147 over the Earl of Chester, who was repulsed from the walls with great loss; whereupon,

says Hovedon,

A synod held in London, in 1075, and presided over by Archbishop Lanfranc, provided moreover for the removal

of Sees from small villages and defenseless towns to places of greater importance in the diocese, and it was thus that the

See of Dorchester, near Oxford, became removed to Lincoln, where Bishop Remigius, a follower of the Conqueror,

erected a magnificent cathedral which he purposed dedicating to the Blessed Virgin, though he died on the day

before the ceremony took place. We find Our Lady of Lincoln frequently mentioned among the sanctuaries which

were regarded by the English with special veneration. The inhabitants of Lincoln who took part with King Stephen

in the civil war, choosing Her as their particular Patroness, attributed to Her intercession the great victory

which they gained in 1147 over the Earl of Chester, who was repulsed from the walls with great loss; whereupon,

says Hovedon, the victorious citizens of Lincoln, filled with joy, gave great thanks and lauds to their Protectress,

the Virgin of Virgins.

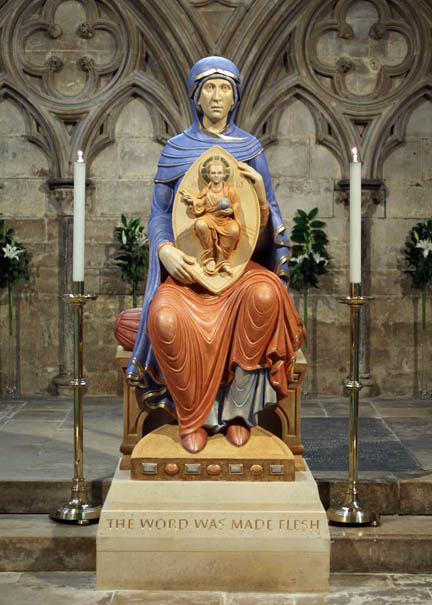

Our Lady of Lincoln continued much in repute; and in the cathedral inventory we find mention

of the great image of Our Lady (replica at right), sitting in a chair, silver and gilt, having a crown on Her head, silver and gilt,

set with stones and pearls, and Her Child sitting on Her knee with one crown upon His head, with a diadem set with

pearls and stones, having a ball with a cross silver and gilt, in His left hand.

At the same synod of 1075, to which reference has been already made, it was decreed that the ancient East Anglian bishopric of Elmham in Norfolk should be removed to Thetford in the same county, where a church dedicated to the Blessed Virgin already existed. Herfast, a Norman prelate appointed to the See, assisted by the pious knight, Roger Bigod, rebuilt this church on a grander scale, and made it the cathedral church of his diocese. But the See was not destined to remain long at Thetford. In 1094, Herbert Losinga again translated it to Norwich, where it has ever since remained, and from that time Thetford, the ancient capital of the East Anglian kingdom, fell into decay.

This transaction appears to have caused great regret to the inhabitants of Thetford, though Roger Bigod made them some amends by planting a community of Cluniac monks in the deserted cathedral church. His first intention had been to atone for the sins of his past life by a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, that he might more fervently worship his Lord in the place where His feet stood when He ascended from the earth; but his steward Etbran dissuaded him from this, and advised him rather to bestow his alms in the foundation of some religious house, where the servants of God might make continual intercession for him and his successors. Convinced by his arguments, Roger bought the church and the lands of St. Mary's, and in 1104 erecting some temporary offices for the reception of his monks, he settled the colony of Cluniacs from the Priory of Lewes in the place, and set about building them a monastery within the city walls.

But it seemed as if the church of St. Mary's were doomed to be always changing its occupants, for a few years later, a certain learned monk named Stephen was appointed Prior, who on coming to Thetford perceived that the site chosen for the monastery was very inconvenient, being quite surrounded by the houses of the townspeople; and with the consent of the founder, removed the foundation to a large, open, and pleasant space outside the walls, and on the other side of the river. The spot chosen was fixed on by King Henry I, who at that time kept his court at Thetford. Herbert, Bishop of Norwich began the digging of the foundation with his own hands, and the Prior and founder, with the other nobles of high rank, laid the first stones. The misfortunes of the men of Thetford, however, were not yet quite complete. Eight days after the foundation of this monastery had been so magnificently begun, Roger Bigod died, and contrary to his written directions, Bishop Herbert came by night, seized his holy body, and caused it to be interred in his new cathedral, nor could the monks ever regain possession of the remains of their founder. However, the enterprising spirit of their new Prior made head against all difficulties and discouragements, and in 1114, the buildings being now complete, the monks took possession, bringing with them all the valuables out of the old church and cloister.

Among other property thus removed, was an image of the Blessed Virgin which had formerly been set over

the high altar of the old church, during the time that it was used as the cathedral of the diocese. It was now placed

over the high altar of the new church (image of ruins below); but in process of time, a finer image being made, the ancient one was taken down

and put in an obscure place. This old image, however, was in the course of a few years to attract far more notice than

the fine new one that had replaced it, and became the chief ornament of a noble chapel, wherein Our Lady of Thetford

was venerated by many a pious pilgrim, down to the disastrous time of the Reformation.

The narrative is thus related by John Brame, a monk of Thetford, in a manuscript still preserved in Corpus Christi College,

Cambridge. There was at that time in the town, he says, a poor workman who incessantly called on the Blessed Virgin for

relief from an incurable disease from which he suffered; and one night She appeared to him, telling him that if he would

be cured, he must hasten to the Prior of Her monastery, and command him in Her name to build Her a chapel on the north

side of the choir, which he had newly repaired. As he paid no attention to this message, She again appeared to him thrice,

whereupon he acquainted the Prior, who being much astonished, resolved to obey the command, and build the chapel in wood.

But the sick man returning to him, desired him on the part of Our Lady to build it of stone, and showed him the exact

spot in which She would have it done. Shortly after this the Prior departed out of the town, and the man going to the

monastery, and not finding him, went to an old monk who had resided many years in the house, and gave him a token where

the foundation-stone of the chapel should be placed, by showing him and everyone else that wished to see it, for two hours

together, the shape of a cross upon it, wonderfully adorned with gold and jewels, which afterwards disappeared.

As the Prior on his return still delayed commencing the building, Our Lady appeared in like manner to a woman in the town,

and bade her go to one of the monks, and command him to bid the Prior build the chapel at once. The woman neglected to

fulfill this behest, whereupon the Blessed Virgin came to her in the night, and blamed her for her neglect, at the same

time touching her arm, of which she immediately lost the use. Perceiving this when she awoke, and grieving for her negligence,

she ran to the monk, and telling him what had happened with many tears, he advised her to offer an arm of wax to the

Holy Virgin, which being done her arm was restored.

The narrative is thus related by John Brame, a monk of Thetford, in a manuscript still preserved in Corpus Christi College,

Cambridge. There was at that time in the town, he says, a poor workman who incessantly called on the Blessed Virgin for

relief from an incurable disease from which he suffered; and one night She appeared to him, telling him that if he would

be cured, he must hasten to the Prior of Her monastery, and command him in Her name to build Her a chapel on the north

side of the choir, which he had newly repaired. As he paid no attention to this message, She again appeared to him thrice,

whereupon he acquainted the Prior, who being much astonished, resolved to obey the command, and build the chapel in wood.

But the sick man returning to him, desired him on the part of Our Lady to build it of stone, and showed him the exact

spot in which She would have it done. Shortly after this the Prior departed out of the town, and the man going to the

monastery, and not finding him, went to an old monk who had resided many years in the house, and gave him a token where

the foundation-stone of the chapel should be placed, by showing him and everyone else that wished to see it, for two hours

together, the shape of a cross upon it, wonderfully adorned with gold and jewels, which afterwards disappeared.

As the Prior on his return still delayed commencing the building, Our Lady appeared in like manner to a woman in the town,

and bade her go to one of the monks, and command him to bid the Prior build the chapel at once. The woman neglected to

fulfill this behest, whereupon the Blessed Virgin came to her in the night, and blamed her for her neglect, at the same

time touching her arm, of which she immediately lost the use. Perceiving this when she awoke, and grieving for her negligence,

she ran to the monk, and telling him what had happened with many tears, he advised her to offer an arm of wax to the

Holy Virgin, which being done her arm was restored.

The chapel was at last built, and judging from the ruins which yet remain, was not much inferior in size to

the choir itself. Desiring to increase the people’s devotion to the Blessed Virgin, the Prior desired the old image

which stood by a door near the chapel to be taken down and newly painted, for it was a point on which our forefathers

showed much solicitude, that the images in their churches, shulde be wel peynted, that they shulde make men fayne

to loke upon them; and styere to devocion.

As the painter was cleaning it, preparatory to beginning his work,

he found a silver plate fastened to the top of the head; and showing it to the Prior and monks, it was taken off in their

presence, and found to conceal an opening, in which were laid many holy relics, carefully wrapped in lead, all of which

had been sent to Prior Stephen by William, Prior of Merlesham, at the request of Hugh Bigod and Sir Ralf, monk of Thetford.

All the relics bore their names, and most of them had been brought from Jerusalem. They consisted of portions of the

Holy Sepulcher, of the sepulcher of the Blessed Virgin, of the rock of Calvary, of the purple robe of Our Lord,

of Our Lady's girdle, of the holy Manger, of the earth found in the sepulcher of St. John the Evangelist;

together with relics of St. Vincent Martyr, St. Leger, St. Barbara, St. Gregory, St. Leonard, and St. Jerome,

with some of the hair of St. Agnes. There were also two relics of English saints, namely a portion of the wooden coffin

in which St. Edmund the Martyr had been laid, and in which his body had been found whole and incorrupt many years after

his death, and some pieces of St. Ethelreda's coffin, wherein she also had been discovered lying as if asleep,

eleven years after her death. The image itself had been made by the aforesaid Sir Ralf, who had been a monk before

they removed from the cathedral, and he had caused to be made for it, at his own expense, a tabernacle adorned with

small images, painting, gold and jewels, and had placed the said relics within the head. And being a great client

of Our Lady, he had also persuaded the Lady Maud de Samundeham to purchase the famous picture of the Blessed Virgin,

then preserved in their refectory, and for all these his labors and services, his anniversary was to be kept yearly

on the Ides of October.

The image was now set up in the new chapel wherein also were kept the relics thus curiously discovered; and persons coming to pay their devotions here, and obtaining many great favors, these were noised about the country and increased the fame of Our Lady of Thetford. Thus a certain woman in Thetford having overlaid her child in the night, and finding it dead, ran with the body in her arms and placed it before the holy image, when it returned again to life. Another woman had lost her voice in consequence of a disease in her throat, and was urged by her friends to go and make her offering to the holy image of Our Lady at Wulpit in Suffolk. But she made signs that she would rather go to the image in the monks’ new chapel, and doing so, her voice was restored. And she declared, on being able to speak, that the Blessed Virgin had appeared to her and touched her tongue; wherefore, in gratitude, she vowed to keep a candle burning before the holy image daily during her life. Another recorded miracle is that granted to William Keddrich, a carpenter of Hokham, and Isabel his wife. For it being harvest time, they according to their custom carried with them to the field their son, a boy of three years old; and while the mother was mowing towards evening the child lay down and fell asleep. Soon after a cart coming into the field, the wheel passed over his head and killed him on the spot. The father was following the cart, and seeing what had happened, he took up his child and ran with him to a doctor in the town, who assured him that the boy was dead. The parents in their sore distress made a vow to make a pilgrimage to Our Lady of Thetford, and about midnight the child returned to life; whereupon the parents fulfilled their vow and made large offerings to the Blessed Virgin.

Norfolk possessed many other images of Our Lady of considerable fame, such as that known as Our Lady of the Oak,

which hung in an oak tree that grew in the churchyard of St. Martin's, Norwich, whence the church itself commonly bore

the title of St. Martin at the Oak (image right). The image was so placed as to be seen from the street, and was greatly venerated.

Pilgrimages were made to it, and it is mentioned by more than one foreign writer. It appears to have first attracted

popular devotion in the reign of Edward II, and many persons left bequests in their wills for painting and adorning this image.

In the reign of Edward VI, the image was burnt, and in order the more thoroughly to eradicate the very memory of it from

the minds of the people, the oak itself was cut down to the bitter regret of the citizens. There was also a famous chapel

of Our Lady attached to the church of the Augustinians which bore the title of the Scala Coeli (Stairway to Heaven),

and was enriched with very large indulgences. Only two other chapels in England enjoyed equal privileges, namely the

Scala Coeli at Westminster, and that at St. Botolph's Church at Boston.

Norfolk possessed many other images of Our Lady of considerable fame, such as that known as Our Lady of the Oak,

which hung in an oak tree that grew in the churchyard of St. Martin's, Norwich, whence the church itself commonly bore

the title of St. Martin at the Oak (image right). The image was so placed as to be seen from the street, and was greatly venerated.

Pilgrimages were made to it, and it is mentioned by more than one foreign writer. It appears to have first attracted

popular devotion in the reign of Edward II, and many persons left bequests in their wills for painting and adorning this image.

In the reign of Edward VI, the image was burnt, and in order the more thoroughly to eradicate the very memory of it from

the minds of the people, the oak itself was cut down to the bitter regret of the citizens. There was also a famous chapel

of Our Lady attached to the church of the Augustinians which bore the title of the Scala Coeli (Stairway to Heaven),

and was enriched with very large indulgences. Only two other chapels in England enjoyed equal privileges, namely the

Scala Coeli at Westminster, and that at St. Botolph's Church at Boston.

But incomparably the most celebrated sanctuary of Our Lady existing not only in Norfolk, but in all England,

was that of Walsingham, the first foundation of which took place in 1061, when the widow of one Ricoldie de Faverches built

a chapel here in all respects like to that of the Holy House of Nazareth. This was more than two centuries before the

miraculous removal of the Holy House to Loreto, for it will be remembered that long before that event the House within

which the Divine Word had been made flesh, formed one of the chief localities devoutly visited by pilgrims to the Holy Land.

A few years after the Conquest, Sir Geoffry de Faveraches or Favercourt, son of the first foundress, endowed the chapel

with lands and revenues and built a church and priory in which he placed a community of Augustinian canons, his own chaplain

Edwin becoming the first Prior. The priory was a grand edifice often rebuilt; but the Chapel of the Annunciation stood

separate from the priory church, and itself enclosed the original wooden chapel containing the famous image (replica below), to which,

says Blomefield, foreigners of all nations came on pilgrimage, insomuch that the number of Her devotees seemed to equal

those of Our Lady of Loreto in Italy; and the town of Walsingham Parva owed thereto its chief maintenance and support.

Henry III paid a visit here in 1248, but it was during the reign of his son Edward I that the pilgrimage

first attained that extraordinary popularity which it retained until the overthrow of religion. This king had a very

special devotion to Our Lady of Walsingham, and attributed to Her intercession his deliverance from death on occasion

of a singular accident that took place at Windsor in 1270, just before he set out on his crusade. He was sitting playing

at chess when he suddenly rose without any apparent reason and left his seat. As he did so a heavy stone detached itself

from the groined roof and fell exactly on the spot where the prince had been sitting. He twice visited the shrine,

once in 1247 and again in 1263, and it is probable that the miraculous translation of the Holy House from Nazareth to Loreto,

which took place in the reign of this monarch, contributed not a little to increase the veneration of the English people

to the sanctuary of Walshingham. No English shrine could boast of equal popularity; and the common people in their

simplicity believed, says Blomefield, that the Milky Way was appointed by Providence to point out the particular

place and residence of the Blessed Virgin, and was on that account generally called the Walsingham Way.

He adds, I have myself heard old people of this country so to call and distinguish it some years past.

But it was not by the English alone that Walsingham was visited; among the list of pilgrims we find the

names of many illustrious foreigners, such as King David Bruce (King David II of Scotland), who came hither in the

reign of Edward II, under a safe-conduct from the English king; and several of the French princes. Most of our native

sovereigns paid their devotions here, and some visited it more than once; King Henry VIII rode hither in the second year

of his reign and made his offerings, having once before, when a youth, performed a pilgrimage to the chapel, walking barefoot

from the town of Barsham, on which occasion he presented Our Lady with a necklace of great value. The last royal visit on

record was that of his consort, Queen Catherine of Aragon, who came here in 1514, whilst the king was in France,

to return thanks for the victory gained over the Scots at Flodden Field.

But it was not by the English alone that Walsingham was visited; among the list of pilgrims we find the

names of many illustrious foreigners, such as King David Bruce (King David II of Scotland), who came hither in the

reign of Edward II, under a safe-conduct from the English king; and several of the French princes. Most of our native

sovereigns paid their devotions here, and some visited it more than once; King Henry VIII rode hither in the second year

of his reign and made his offerings, having once before, when a youth, performed a pilgrimage to the chapel, walking barefoot

from the town of Barsham, on which occasion he presented Our Lady with a necklace of great value. The last royal visit on

record was that of his consort, Queen Catherine of Aragon, who came here in 1514, whilst the king was in France,

to return thanks for the victory gained over the Scots at Flodden Field.

Erasmus, who visited Walsingham before the suppression of the monasteries, has described it in vivid terms

in his Colloquy entitled Peregrinatio Religionis Ergo. There is a college of secular canons here,

he says,

with scarce any revenues besides the offerings made by the pilgrims to the Blessed Virgin Mary, of which the most

valuable are preserved. The church is splendid and beautiful, but the Virgin dwells not in it, for the church,

out of reverence, is given to Her Son. She has a chapel so contrived as to be on the right hand of Her Son.

In this unfinished chapel is another little narrow chapel, all of wood, with an open roof, and on each side of it a

narrow door through which the pilgrims are admitted to pay their devotion and make their offerings. There is scarcely

any light except that from the burning wax tapers, which have a delightful smell, but within all is bright and shining,

glittering all over with gold, silver, and jewels, so that you would take it to be the abode of the gods. A canon-resident

is ever at the altar to receive and take care of the offerings.

On this occasion Erasmus left as his offering a

fair copy of Latin verses. Among the other offerings which decorated the shrine was an image of gilt silver bequeathed

in his will by Henry VII, and a certain tablet with an image of Our Lady covered with glass bequeathed by

Isabel Countess of Warwick in 1439, who also left to Our Lady of Walsingham her gown of cloth of gold with wide sleeves,

and a tabernacle of silver like in the timbre (style) to that of Our Lady of Caversham.

Erasmus likewise describes some of the other offerings left in thanksgiving or commemoration of special favors obtained;

and among these was a plate of copper engraven with the effigies of a knight on horseback, which was nailed on the gate

of the priory. This was to commemorate an event which took placed in the year 1314. On the north side of the priory,

leading into the close, was a very low and narrow wicket door, through which it was difficult to pass on foot, it not being

more, says an old manuscript, than an elne hye and three-quarters in bredth (about four feet high and three feet wide).

And a certain Norfolk knight, Sir Raaf Boutetourt, armed head to foot and on horseback, being... pursued by a cruel enemy

and in the utmost danger of being taken, made full speed for this gate, and invoking Our Lady for deliverance he immediately

found himself and his horse within the priory close or sanctuary, in a safe asylum, and so fooled his enemy.

In the household accounts of Henry Percy, fifth Earl of Norhumberland, we find the following entries:

Item, My Lord useth and accustomyth to send yerely to the upholdynge of the light of wax which his Lordship fyndith

birnynge yerely befor Our Lady of Walsingham... 6 shillings, 7 pence... Also my Lord useth and accustomyth to send yerely

to the Channon that kepith the light before Our Lady of Walshingham, for kepynge of the said light, lightynge of it at all

service times dayly thorowt the yere, 12 pence...

Besides these offerings we find in the same document notices of

offerings made to Our Lady in the White Frerers

at Doncaster, to the Holy Blood of Hales, and St. Margaret's in

Lincolnshire.

One of the last bequests to the sanctuary was that of Queen Catharine of Arragon, who in her will desired that a person should make a pilgrimage to Our Lady of Walsingham for the repose of her soul, distributing 200 nobles in charity on the road.

Not a stone remains of Our Lady's chapel; it was entirely destroyed in the reign of Henry VIII (the image

at right is of a more modern Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, housing the replica of the original), when the image,

so long the object of pious veneration, was taken to Chelsea and there publicly burnt. In a letter from Roger Townsend

to Lord Cromwell, we find mention of a woman punished for reporting a miracle

Not a stone remains of Our Lady's chapel; it was entirely destroyed in the reign of Henry VIII (the image

at right is of a more modern Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, housing the replica of the original), when the image,

so long the object of pious veneration, was taken to Chelsea and there publicly burnt. In a letter from Roger Townsend

to Lord Cromwell, we find mention of a woman punished for reporting a miracle done by the Image sith (after)

the same was brought thence to London;

howbeit, he adds, I cannot perceive but that the said image is not yet

out of some of their heads.

Bishop Latimer (who showed himself particularly forward in all these works of sacrilege,

and who, it will be remembered, preached at the execution of Friar Forrest, when that holy Martyr was suspended by the

middle and roasted at a fire made of an image of Our Lady and a great Cross, brought up from Wales for the occasion)

also writes to Lord Cromwell as follows: I trust your lordship will bestow our great Sybil (the image of Our Lady)

to some good purpose, ut pereat memoria cum sonitu (that the memory may perish with the sound). She hath been the

devil's instrument to bring many I fear to eternal fire. Now She Herself with Her old Sister of Walsingham,

and Her young Sister of Ipswich, with their two Sisters of Doncaster and Penryesse would make a jolly muster in Smithfield.

They would not be all day in burning.

Our Lady of Ipswich, mentioned above, appears to have been a very popular though less ancient place of pilgrimage. The image stood in a chapel, commonly called Our Lady of Grace, situated at the northwest corner of the lane without the west gate, which went by the name Lady Lane. It was much frequented in Catholic times, but particularly under the Tudor sovereigns. We find it named among the sanctuaries to which Queen Elizabeth of York, the consort of Henry II, made her yearly offerings; the others being Our Lady of Windsor, Our Lady of Eton, Our Lady of Caversham, Our Lady of Sudbury, Our Lady of Wulpit, and Our Lady of Stoke-by-Clare.

It was to the chapel of Our Lady of Ipswich that Cardinal Wolsey, himself by birth an Ipswich man, ordered a yearly procession to be made by the college which he founded in his native town, on the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, the special Patroness of his foundation. An interesting notice of this famous pilgrimage occurs in St. Thomas More's Dialogues, and we will quote the passage entire:

As for the point that we spoke of, concerning miracles done in our days at divers images where

pilgrimages be, yet could I tell you some such done so openly, so far from all cause of suspicion, and thereto testified

in such sufficient wise that he might seem almost mad, who, hearing the whole matter, would mistrust the miracles.

Among which, I durst boldly tell you for one the wonderful work of God that was within these few years wrought in

the house of a right worshipful knight, Sir Roger Wentworth, upon divers of his children, and specially one of his daughters,

a very fair young gentlewoman of twelve years of age, in marvelous manner vexed and tormented by our ghostly enemy the devil,

her mind alienated and raving with despising and blasphemy of God, and hatred of all hallowed (blessed) things,

with knowledge and perceiving of the hallowed from the unhallowed, all were she nothing warned thereof. And after that,

moved in her mind and admonished by the will of God to go to Our Lady of Ipswich; in the way of which pilgrimage she

prophesied and told many things done and said at the same time in other places, which were proved true; and many things

said lying in a trance, of such wisdom and learning that right cunning men highly marveled to hear of so young an

unlearned maiden, when herself knew not what she said, such things uttered and spoken as well learned men might

have missed with a long study. And finally, being brought and laid before the image of Our Lady, was there in the sight

of many worshipful people so grievously tormented, and in face, eyes and countenance, so grisly changed with her mouth

drawn aside, and her eyes laid out upon her cheeks that it were terrible sight to behold. And after many marvelous

things at the same time shown upon divers persons by the devil through God’s permission, the maiden herself in the

presence of all the company was restored to her good state, perfectly cured and suddenly. And in this matter no

pretext of begging, no suspicion of feigning, no possibility of counterfeiting, no simpleness of the seers,

her father and mother right honorable and rich, sore abashed to see such things in their children, the witnesses of great

number, and many of great worship, wisdom, and good experience, the maid herself too young to deceive, and the fashion

itself too strange for any man to feign. And the end of the matter virtuous, the virgin so moved in her mind by the

miracle that she forthwith, in spite of all her father could do, forsook the world, and preferred religion in a very

good and pious company at the Minoresses of St. Clare, where she hath lived well and graciously ever since.

Who would believe that a near descendant of this very Sir Roger Wentworth should have been the man to lend his ready aid in destroying the sacred image?

On December 1, 1529, Thomas, the descendant of this Sir Roger, was summoned to Parliament by writ as

Lord of Wentworth, and is, it is presumed, the Lord of Wandeford

mentioned in a letter addressed by

William Lawrence to Thomas Cromwell: Pleaseth your good Lordship,

he says, according to your commandment

I have been with my Lord Wandeford, the which was very desirous and glad to hear of your lordship's good health.

I opened to him your mind concerning the image of Our Lady (of Ipswich). His good counsel and help of his servants was

so ready that She was conveyed into the ship, so that very few were privy to it, and shall come up so shortly as the wind

will serve.

By the expressions here used it is evident that the sacrilegious removal of the image would have been

opposed by the people, and that considerable caution had to be used by those entrusted with the disgraceful business.

The image was sent to London, and received by Thomas Thacker, Cromwell's steward, who writes to his master informing him that

Our Lady that was at Ipswich

is now in his house near the Augustinian Friars, and bestowed in the wardrobe of beds

(hidden in a closet), till his lordship's pleasure shall be known. There is nothing about Her,

he adds,

but two half shoes of silver, and four stones of crystal set in silver.

A little later he writes: I have received

from my fellow, William Lawrence from Ipswich, Our Lady's cote with two gorgetts of gold to put about Her neck;

and an image of Our Lady, of gold, in a tabernacle of gilt silver with the feather in the top of it gold;

and a little relic of gold and crystal with Our Lady's milk in it, as they say.

The image was shortly afterwards publicly burnt. (Fr. Northcote was probably ignorant of the tradition

preserved in the town of Nettuno, Italy, by which it is believed that the image venerated there as Madonna delle Grazie is

none other than Our Lady of Ipswich. It is said to have been saved from the scheduled burning by Catholic sailors,

who smuggled it to Italy. There is much evidence to support this theory, including the fact that it arrived in

Nettuno in 1550, wearing the two half shoes of silver

described above. It was frequently visited by St. Maria Goretti

and is still venerated in Nettuno to this day.) It was probably one of those which at the time of the Reformation

was regarded with peculiar veneration by the people, and which was on that account specially obnoxious to the iconoclasts,

for in the homily against the peril of idolatry it is named together with Our Lady of Walsingham and Our Lady of Willesden.

This last-named image was venerated in the church of St. Mary's Willesden (replica at right), a parish lying on the western

boundary of Hampstead. So early as the year 1251 we find an inventory of the goods and ornaments belonging to Willesden

church which includes a scarlet banner with a figure of the Blessed Virgin worked in cloth of gold, and two images of Our Lady;

and the pilgrimage is believed to have been of very ancient date. In the same neighborhood existed the miraculous sanctuary

of Our Lady of Muswell, a chapel standing on the hill which separates Hornsey from Finchley Common. Norden,

in his Speculum Britanniae, notices this chapel and says that it contained an image

This last-named image was venerated in the church of St. Mary's Willesden (replica at right), a parish lying on the western

boundary of Hampstead. So early as the year 1251 we find an inventory of the goods and ornaments belonging to Willesden

church which includes a scarlet banner with a figure of the Blessed Virgin worked in cloth of gold, and two images of Our Lady;

and the pilgrimage is believed to have been of very ancient date. In the same neighborhood existed the miraculous sanctuary

of Our Lady of Muswell, a chapel standing on the hill which separates Hornsey from Finchley Common. Norden,

in his Speculum Britanniae, notices this chapel and says that it contained an image whereto was continual resort

in the way of pilgrimage.

This arose from the miraculous cure performed (according to a tradition in his time still

current) on a king of Scotland, by the waters of a spring called Mousewell, or Muswell, on the spot where the chapel stood.

Lysons observes that the well still remains, but is not famed for any extraordinary virtues, whence we may infer that the

cures wrought there in old time are not to be attributed to the medicinal properties of the water. The chapel was

attached to the Priory of Clerkenwell, and appears to have been built about the year 1112.

Among the other shrines already named as those to which Elizabeth of York made her annual offering,

that of Caversham (replica below) was held in great repute. The image appears to have stood in a chapel attached to the church of

Caversham in Buckinghamshire, which was granted in 1162 by King John to the Augustinian Canons of Nutley or Notcele Abbey

in the same county. The chapel was then already in existence, and was held of sufficient importance to be separately named

in the grant. Afterwards the canons coming into possession of a manor at Caversham, erected a cell to their monastery,

which Tanner says was much enriched by the offerings made in the chapel of Our Lady. Dugdale in his Baronage

speaks of the offerings made by Isabel Countess of Warwick to Our Lady of Caversham, and Gilbert Marischale, Earl of Pembroke,

granted to the canons the tithes of all his mills and fisheries at Caversham, together with the annual sum of twelve

shillings, for the maintenance of two lamps to burn continually before Our Lady for the salvation of his soul and the soul

of his brother. This chapel is not to be confused with the chapel of St. Anne that formerly stood on the bridge,

wherein was preserved a certain famous relic which Dr. London, one of the visitors appointed by Henry VIII, describes as

the angel with one wing, that brought to Caversham the spear-head with which Our Lord was pierced on the Cross.

We confess our inability to throw any light on the history of this remarkable relic, the description of which probably

owes something to the malice of the narrator.

Of Our Lady of Wulpit, a sanctuary often named in ancient testamentary documents, little can now be told.

The image stood in the Lady chapel attached to the parish church of Wulpit, a village lying between Bury and Stow Market

in Suffolk. In a close near the east end of the church may still be seen a spring called Our Lady's spring,

which supplies a large moat with remarkably clear water. Tradition affirms that the pilgrims were wont to drink

of this spring and that a chapel formerly stood near it, of which however no vestiges now remain.

Of Our Lady of Wulpit, a sanctuary often named in ancient testamentary documents, little can now be told.

The image stood in the Lady chapel attached to the parish church of Wulpit, a village lying between Bury and Stow Market

in Suffolk. In a close near the east end of the church may still be seen a spring called Our Lady's spring,

which supplies a large moat with remarkably clear water. Tradition affirms that the pilgrims were wont to drink

of this spring and that a chapel formerly stood near it, of which however no vestiges now remain.

Stoke by Clare was another Suffolk sanctuary. At first an alien priory of Augustinian Friars, it was converted into a collegiate church in 1415 by Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March. The chapel of Our Lady attached to this church is named in the college statutes as the Capella Beatae Mariae de Stoke, and appears to have been a distinct foundation.

We have named so many Norfolk and Suffolk pilgrimages that our readers may perhaps be impressed with the

idea that the East Anglian population surpassed their neighbors in devotion to the Blessed Virgin. But in point of fact

most English counties were equally rich in these holy places. Thus Kent could boast of Our Lady of Gillingham, of Chatham,

of Bradstow, and of Canterbury. The niche in which stood the famous statue of Our Lady of Gillingham may still be seen

over the west door of the ancient parish church which likewise contained a Cross held to be miraculous. Yet more celebrated

was the neighboring sanctuary of Chatham, an ancient Norman church now destroyed, in which existed many singular and

beautiful remains of ancient architecture. Under the entrance arch to the north porch appeared an empty niche and bracket

with figures of angels at the sides extending their wings as if over the head of the figure of Our Lady that formerly

occupied it, and other angels bending prostrate towards Her. In this niche the famous image is believed to have stood,

and some years ago, when the old church was pulled down to be replaced by what is termed, by the local historian,

a neat edifice of brick nearly square,

fragments of sculpture richly painted and gilt were discovered among

the materials with which the east window had been built up. Among these fragments were headless figures of the Blessed Virgin

and Her Divine Child. The figure of Our Lady was dressed in a mantle fastened across the breast by a fibula in which still

remained some pieces of colored glass in imitation of precious stones. This was in all probability the ancient and

much-honored statue of Our Lady of Chatham, desecrated at the time of the Reformation,

and broken up with other

building rubbish for the purpose of yet further defacing the church in which it had been honored for centuries,

by blocking its window.

Mention of both these last-named sanctuaries occurs in a legend preserved by Lambarde in his Perambulation

of Kent,

and related by him with certain irreverent comments which the reader shall be spared. It happened on a

certain day, he says, that the corpse of some unknown man was cast on shore somewhere within the parish of Chatham,

and was by charitable persons given burial in the church-yard. That night, however, as the parish clerk of Chatham slept,

he was aroused by a voice at his window, and asking who was there, it was answered that Our Lady of Chatham willed him to

know that the person lately buried near unto the place where She was honored was a sinner, which so offended Her eye

with his ghastly grinning, that unless he were removed, She could not but (to the great grief of good people) withdraw

Herself from that place, and cease Her wonted miraculous working among them,

and therefore She willed him to take up

the corpse and cast it back into the river. The clerk accordingly arose, and going to the church-yard disinterred the body,

and conveyed it to the spot where it was first found. Being carried away by the waters it was again taken out by some of

the parishioners of Gillingham, who did as those of Chatham had done before them, and buried it in their church-yard.

But see what followed: not only the Cross of Gillingham, that a while before bestowed many miracles, was now deprived

of its virtue, but even the very earth where the carcass was laid did continually forever after sink and settle downwards.

Another Kentish sanctuary was that of Our Lady of Court-up-Street, rendered famous in the days of Henry VIII as the scene of the pretended revelation of Elizabeth Barton, the Maid of Kent, though it would seem to have been held in popular veneration long before her time.

Leaving these more obscure localities, however, we will betake ourselves to the sacred soil of Canterbury,

for so it must surely be regarded by English eyes – where vestiges even yet remain of the old devotion. We have already

seen St. Dunstan favored with heavenly ecstasies in the Lady chapel of the old Saxon cathedral. In the fabric which rose

over its ruin, not one but several altars were dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. The exquisite Lady chapel, now known as

the Dean's chapel, was built by Prior Goldstone about the year 1460, probably on the site of a more ancient structure.

The stone screen leading into the choir displays over its arched doorway a niche under a triple-headed canopy within which

formerly appeared a statue of the Blessed Virgin, under twelve other niches which contained silver images of the Apostles.

On the spot called the Martyrdom, from the fact of its being the scene of the martyrdom of St. Thomas Becket,

a wooden altar was erected to Our Lady, whereon was preserved the sword’s point, which broke off in the hands of the

assassin whilst giving the fatal stroke.

Leaving these more obscure localities, however, we will betake ourselves to the sacred soil of Canterbury,

for so it must surely be regarded by English eyes – where vestiges even yet remain of the old devotion. We have already

seen St. Dunstan favored with heavenly ecstasies in the Lady chapel of the old Saxon cathedral. In the fabric which rose

over its ruin, not one but several altars were dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. The exquisite Lady chapel, now known as

the Dean's chapel, was built by Prior Goldstone about the year 1460, probably on the site of a more ancient structure.

The stone screen leading into the choir displays over its arched doorway a niche under a triple-headed canopy within which

formerly appeared a statue of the Blessed Virgin, under twelve other niches which contained silver images of the Apostles.

On the spot called the Martyrdom, from the fact of its being the scene of the martyrdom of St. Thomas Becket,

a wooden altar was erected to Our Lady, whereon was preserved the sword’s point, which broke off in the hands of the

assassin whilst giving the fatal stroke.

From the Martyrdom is a descent to the crypt or Undercroft, supposed to be part of Lanfranc's structure, and undoubtedly of Norman work. Here stood the celebrated chapel of Our Lady Undercroft, situated exactly under the high altar of the cathedral. Even in its present ruinous condition it displays remains of its former splendor. On the vaultings may be seen traces of brilliant blue coloring on which appear small convex gilt mirrors, and gilded quatrefoils. The royal arms are painted in the center, and forty shields are emblazoned on the lower part of the arches. This chapel was also enriched by Prior Goldstone, and the armorial bearings, which mostly belong to Lancastrian nobles of the court of King Henry VI, appear to have been placed there as memorials of notable offerings at the shrine.

In a canopied niche at the east end above the altar, stood the image of Our Lady Undercroft on a rich pedestal

sculptured in relief with subjects from her life. The Annunciation may still be traced, but the other sculptures are now

destroyed. This chapel,

says Erasmus, is not showed but to noblemen and special friends. Here Our Lady hath

an habitation, but somewhat dark, enclosed with a double rail of iron, for fear of thieves, for indeed I never saw a

thing more laden with riches. Lights being brought we beheld a more than royal spectacle; which in beauty far surpassed

that of Walsingham.

This chapel is one of those which retains the most distinct traces of its former character, and if in its present state of obscurity and abandonment it should ever chance to be visited by the Catholic pilgrim, he may at the same time satisfy his devotion by visiting the tomb of St. Dunstan, whose ashes repose in the same crypt, and but a few yards distant from this once famous sanctuary.

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com