In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

The Order of Citeaux may in some sense be called an English Order. Not only was St. Stephen Harding, one of its

first founders, an Englishman by birth, but the Order seems to have been adapted in a very special way to the habits and

requirements of English devotion, if we may judge from the extent and rapidity with which it was propagated in this island.

The Abbeys of York, Waverly, Buildewas, Garendon, Tintern, Rievaulx, Fountains, and Furness were all founded in England before

the death of St. Stephen, and to use the expression of his biographer, the Order had taken to itself all the quiet nooks and

valleys, and all the pleasant streams of old England,

to which it was peculiarly suited by its agricultural character,

and perhaps also by its union of manual work with contemplation.

It is no less true that the Cistercian Order was one of those which merited in a rigorous sense to be denominated the Order of Mary. John, Abbot of Citeaux, in his Liber Privilegiorum, declares that this was the first Order in the Western Church dedicated in honor of the Blessed Virgin, and among the rules drawn up by Blessed Alberic in the commencement of the Order, was one which established that all their churches and monasteries without exception should be dedicated in honor of the Mother of God. Pope Gregory X, in one of the Bulls granted by him in favor of the Order, describes it as standing on the right hand of the Spouse arrayed in golden vestments, and distinguished above every Order in the Church for its devotion to the Sacred Virgin; and this devotion was outwardly expressed by exchanging the black habit of the old Benedictines for one of white, which, according to the Cistercian traditions, was given to Blessed Alberic by the hands of the Blessed Virgin Herself.

Another tradition affirms that the white woolen girdle worn by the Spanish Cistercians over their scapular,

was first assumed in commemoration of a favor granted to St. Stephen, who as he one day worked in the fields found himself

hindered by his long scapular, when the Blessed Virgin appeared to him, and girded him with a white girdle, which confined

the habit and scapular. He is also said to have received a miraculous intimation of his approaching death, when praying

before an image of Our Blessed Lady.

Another tradition affirms that the white woolen girdle worn by the Spanish Cistercians over their scapular,

was first assumed in commemoration of a favor granted to St. Stephen, who as he one day worked in the fields found himself

hindered by his long scapular, when the Blessed Virgin appeared to him, and girded him with a white girdle, which confined

the habit and scapular. He is also said to have received a miraculous intimation of his approaching death, when praying

before an image of Our Blessed Lady.

Legends of this sort may at least be taken as showing the kind of devotion which existed in the Order. It was placed in a direct and very special way under the patronage of Mary; all its churches and monasteries bore Her name, and all its members inherited a certain familiar affection towards Her, such as favored children are permitted to feel and express towards an indulgent mother.

If this were the true Cistercian spirit, it certainly in no degree decayed when the Order was transplanted into England, and the history of not a few of the English Cistercian Abbeys presents us with legends in which the Blessed Virgin is represented as directly assisting in the foundation of Her favorite sanctuaries. Of these we will quote but two, of which the first shall be that which attaches to the origin of Kirkstall Abbey, founded in the reign (1135-1144) of King Stephen by Henry de Lacy, in consequence of a vow he had taken to build some monastery in honor of Our Blessed Lady if he should recover from a dangerous sickness. On his restoration to health, he lost no time in accomplishing the vow, and made over the estate of Bernoldwic, which he held under Hugh Bigod, Earl of Norfolk, to the monks of Fountains, who in 1147 sent thither a colony of twelve monks and ten lay brothers, headed by their prior Alexander as Abbot. They changed the name of the place to St. Mary’s Hill, and remained there six years. But the site had not been well chosen. The air was unhealthy, and they suffered not only from a succession of bad harvests, but also from the depredations of the wild bandits with which the civil wars had filled the land.

Abbot Alexander greatly desired to find some spot better fitted for a monastic residence; and later going on a journey, he chanced to pass through a valley which at that time was thickly shadowed with woods which clothed its sides. It was called Airdale from the river Air which ran through it, a clear and beautiful stream, such as Cistercian monks loved to have near their dwellings. In short, the spot seemed to present every convenience for a foundation; plenty of wood and water, a site sheltered from cold winds by the lofty hills, and abundance of good stone for building. Though now scarcely three miles from the great manufacturing town of Leeds, it was then a solitary wilderness – inhabited only by a few brethren, whom the Abbot found leading an eremitical life in the woods.

He inquired of them their order of life, and how they had come hither, and who, moreover, had given them permission

to settle in this valley. Then one of them, whose name was Seleth, and who acted as their superior, made answer, saying, I was born

in the southern parts of this kingdom, and came hither in consequence of a divine revelation. For when I was in my own country,

a voice thrice sounded in my ears as I slept, saying, 'Arise, Seleth, and go into the province of York, and seek diligently for a

valley named Airdale, for a certain spot that is called Kirkstall, for there I have provided a habitation for brethren who are to

serve my Son.' 'And tell me, who art Thou,' I asked, 'and Who is Thy Son that we must serve?' 'I am Mary,' She replied, 'and My Son

is Jesus of Nazareth, the Savior of the world.' Awaking, therefore, I considered in my mind what I ought to do concerning the

heavenly revelation; and casting all my care upon the Lord, I left my house and my servants without delay and set out on my journey.

And directed by Her who had called me, and who guided my steps, I reached this valley which thou seest without any difficulty,

and obtained from some herdsmen this spot in which we live, and which is called Kirkstall. I remained alone for a long time living

on herbs and roots and such alms as I received from Christian charity. But afterwards these brethren joined me, and we have followed

the rule of the brethren of Leruth, having nothing of our own, and living by the labor of our own hands.

The Abbot listened attentively, and considering every particular of the spot, he saw that it was both most pleasant and

beautiful, and also admirably well fitted to the dwelling of monks. He found little difficulty in persuading the hermits to choose a

more perfect way of life, and to enroll themselves among his community. And their former benefactor, Henry de Lacy, used his interest

with William de Poitou, lord of the territory, to make over to the monks the valley with all its woods and water, so that in 1152 they

were able to take possession of it, and to commence the building of that beautiful abbey, the ruins of which we still admire (see image above).

Whatever the primitive conditions of the place,

says Stephens, the continuator of Dugdale, for the Cistercian monks always

founded their monasteries in places that had never before been cultivated or inhabited, it was afterwards a most pleasant seat,

adorned with gardens, dovecotes, etc., and whatever was either for use or ornament; and also conveniently seated on the banks of a

delicate river, calm and clear, which has perhaps contributed to the misnomer of the place, which is frequently called Christall

instead of Kirkstall.

From Kirkstall we will pass on to another Yorkshire Abbey, that of Joreval (also called 'Jervaulx'), a colony from that of Byland, whence in the year 1150 twelve monks were sent forth, headed by Abbot John Kingston, carrying with them the Rule of St. Benedict and a few relics as their only treasures.

It was on Wednesday, the 8th of March, when having received the blessing of the Abbot of Byland, they set out on their

journey towards a pleasant valley on the river Eure, having, says the monk Serlo, Jesus Christ as their Guide, and His Blessed Mother

Mary for their Comforter, as Abbot John often declared to one Abbot Roger, manifesting with tears the revelation made to him.

The revelation here spoken of is more particularly related by Richard, afterwards Abbot of Savigny, and we shall give his narrative as it stands in all its simplicity:

When John, first Abbot of Joreval, and his twelve monks first left our house to go to Joreval, they rested the first night at a certain village, the name of which I have often heard, but at this moment forgot, where the following revelation was granted in sleep to the Abbot John. It seemed to him that he was at our house at Byland, and that Abbot Roger commanded him to go forth with some of our monks to a far country, as if to receive orders; and as he went out through the cloister he saw in the midst thereof a certain Lady, nobly dressed and adorned, and of surpassing beauty, holding by Her left hand a fair Child, Whose face was like the light of the moon. The boy plucked a beautiful bough from a little tree that stood in the center of the cloister quadrangle, and having done so, they both vanished from his sight.

Then he went to the gate, and there he found his companions ready and awaiting him; and they went out, and as they went

along, Abbot John said to them, Do ye know well the road and the place, whither we are going?

And they replied that they did not.

To whom he made answer, Truly, I supposed that you had known it, and now see, we have entered a thick and shady wood, and if we lose

our way, who will guide us?

But one of them said, Let us go on in confidence, for as I trust, we cannot wander far out of

our way.

When they had gone on a little further, it seemed to him that they became quite surrounded by thorns and brambles and

high rocks, where they could see no path, neither could they retrace their steps. So as they hesitated and bewailed themselves,

Abbot John proposed that they should say their Hours and the Gospel; and when they had finished, lo! the beautiful Lady and Her Son,

Whom he had before seen in the cloister, appeared once more; and he said, O fair and delightful Lady, what dost Thou in this desert,

and wither art Thou going?

To whom She made answer, I am often in desert places, and I come from Rievaulx and Byland,

where I have been speaking with the abbots, and with certain monks who are specially dear to Me, and I am now going on to Newminster

to console my beloved Abbot there, and certain other of my monks.

Then said Abbot John, Whereas Thou art but one, how is it

that one friend does not suffice Thee, but that Thou hast many, and those far distant?

And She replied, Truly I have One,

Who has chosen Me for Himself, and from Whom I am never separated, either in presence or in will; nevertheless it seems good to Me

to seek other friends also who love Me faithfully next to Him; yet nevertheless our love, ever perfect, never decreases, but always

augments.

Then said John, Good Lady, I humbly entreat Thee to guide me and my companions who have wandered into this unknown

and narrow place, and to set us in the road towards the city, where by the help of God these monks are to receive orders; and I ask

Thee to do this for the love of Thy friends at Byland, whence we also come.

And She replied, You say truly that you belong to

Byland, but as a part belongs to the whole, as members to the head. For you were of Byland, but now you are of Joreval.

And as She named Joreval he marveled, and said, Good Lady, lead us to Joreval, for it is thither we are going.

Then looking at

Her Son She said, Sweetest Son, for the love wherewith Thou hast ever loved Me, be a guide to these brethren who are our friends,

for I am called elsewhere.

And so saying, She departed. But the Child, holding out the branch which He had plucked in the cloister

of Byland, with a clear voice and smiling countenance said, Have confidence, and follow Me.

And they did so, walking though

rough and difficult ways, yet without feeling fatigue. And behold! an infinite number of little birds, as small as sparrows,

and of unspeakable whiteness, flew down on to the bough which the Child held, and there they continued singing the hymn

Benedicite omnia opera Domini Domino, whereby the monks were so much refreshed, that they felt neither weariness nor difficulty

of any kind from their journey. At last they reached a wild uncultivated spot where the Child planted His branch in the earth with

the birds singing on it, and said, Here very soon God will be adored and invoked,

and as it seemed in a moment, the branch

grew into a great tree all covered with white birds. Rest here,

continued the Child, and restore your strength,

for you can see from hence the place whither you are going, and the way leading thereto has been sufficiently shown you.

And with that, He disappeared.

Ruins of Joreval Abbey.

Now Abbot John slept but little after this, but lay awake revolving these things in his mind, wondering much,

and greatly consoled at the vision. Very early in the morning he and his monks arose, and having said their matins, they proceeded

by the light of the moon and stars. About daybreak they entered a village, the inhabitants of which were just rising, and hearing

a great barking of dogs, some of them looked out of their windows into the road, and seeing a number of men passing by clothed in white,

one of them said, Who are all these men in white going by?

Then Abbot John stood under the shadow of the wall that he might hear

what further would be said about them; and another man made answer and said: Yesterday I was told that an abbot and twelve monks

were about to move from Byland to Joreval;

which a third man hearing, went out of the house with great joy, and gazing a little

at the moon, the stars, and the signs of the firmament, he said: These good men have moved at a happy time, for within a brief space,

that is to say thirty or forty years, they will attain to much prosperity, and enjoy abundance of all temporal things.

Having heard these words Abbot John proceeded on his way rejoicing, and comforting his companions as well with the words of the

simple man as at the revelation he had before received.

This narrative,

continues Richard, he who reads may interpret as he wills; it suffices to me to relate it

simply as I have heard it told by our elders, and that not once, but many times.

Two other Cistercian Abbeys owed their foundation to vows made by English princes to the Blessed Virgin in a moment of extreme peril. One of these was the Abbey of Vale Royal in Cheshire founded by King Edward I, who during the lifetime of his father returning to England from some foreign expedition, was in danger of shipwreck. And as they every moment expected to be swallowed up by the waves the prince proposed to his companions that each one should make some promise to God, whatever the Spirit of God might inspire. The storm, however, continued to rage, until the prince, believing that their last hour was come, humbly vowed to God and the Blessed Virgin, that if they reached land in safety he would build a Cistercian Abby in honor of Our Lady and endow it with revenues for the support of a hundred monks. Scarcely had he pronounced the words, than the winds subsided, and the ship, which was so shattered and broken that the water was rushing in through many leaks, nevertheless was as it were miraculously brought safe to the shore, which they beholding, gave thanks to the Glorious Virgin who suffers not Her votaries to perish. The prince was the last to leave the vessel, and as soon as he had set his foot on land, it parted in two and was swallowed up in the waves.

This event took place it would seem before the commencement of the Baron's Wars, for the Abbey register goes on to tell us that after his arrival in England, the quarrel between King Henry and his barons having broken out, Prince Edward was taken prisoner and confined in the city of Hereford, at which time he received much help and comfort from the monks of Dore. And calling to mind his vow, he resolved on regaining his liberty to choose his community out of their number. The new foundation was first of all placed on his own manor of Dernhale, but was afterwards removed to Kingsdale or Vale Royal, a spot which had before been the habitation of robbers, and bore the name of Munchenwro. Yet bad as was the previous reputation of the place, miraculous signs had not been wanting, which seemed to indicate that it had been chosen to become a holy sanctuary. Men said that they had heard from their fathers how many years before the foundation of the Abbey, when the valley was still a vast and wild solitude, the shepherds who fed their flocks there had been wont on all solemn feasts of the Blessed Mother of God to hear voices as if singing in the air, and a clear light appeared on the spot, which turned night into day; moreover they heard as it seemed the sweet chiming of bells. And after the church was built the country people beheld it surrounded with light as if it were on fire, so that great numbers ran together to extinguish the conflagration.

In 1277 King Edward himself laid the first stone of the new Abbey, two other stones being laid by Queen Eleanor of Castile,

one for herself, and the other for her infant son Alphonso. But the monks did not take possession of this monastery till the Feast of the

Assumption 1330, continuing to reside in some temporary buildings erected by the King until the completion of the grander edifice.

The ceremony was attended by such a concourse of people that the Abbey walls could barely contain all the guests. There was a plentiful

feast provided and music of all kinds, and all did their best to honor Her in whose name this new sanctuary had been dedicated as a

perpetual remembrance of the deliverance She had granted to Her clients. One incident is remarked by the historian and piously

interpreted by him as a sign of Our Lady's favor. For forty days before the feast, he says, there had been such torrents of rain that

the whole country round about was flooded, and you would have thought that the deluge of Noe was coming again on the earth, but on the

Vigil of the Assumption, and during the two following days, the air cleared, and not a drop of rain fell. But so soon as everything

was over, and the guests had departed, it began again, and continued as heavily as before. Who can doubt, he asks, that this serenity

of the air was a sign that the Sacred Virgin rejoiced at the coming of Her monks to this place, saying, Here will I dwell, for I have

chosen it,

for it is surely of such as them that those other words are written in the Apocalypse, They shall walk with me in white

robes, for they are worthy.

It only remains to add that King Edward amply fulfilled his vow, and that the endowments of his Abbey were worthy of a

royal foundation. But besides his gifts of lands and revenues he bestowed upon the monks one donation hardly less precious in their eyes.

This was a piece of the True Cross which he brought with him from the Holy Land after his return from the Crusade, and which the

historian calls a pulcherimam portionem (a most beautiful portion), adding that this most religious King had been accustomed to

wear it round his bare neck in all his battles, and that by virtue of it he overcame all his enemies. He added also a great number of

other relics canonically approved,

as well as a profusion of sacred vessels, books and vestments.

The other Cistercian sanctuary which owed its construction to the gratitude of a Plantagenet king towards Our Blessed Lady,

was that which bore the title of Our Lady of Graces by the Tower (the Plantagenet dynasty consisted of those kings of England

descended from the Norman duke, Count Geoffrey of Anjou. They began with King Henry II in 1154, and ended with King Richard III in

1485). It was founded by King Edward III in 1349, partly in consequence of a vow he had made owing to a storm at sea, and partly,

as we learn from the charter of his son Richard II, in gratitude for the many and abundant graces and deliverances from perils by

sea and by land which he had received from the clemency of Our Lord Jesus Christ through the intercession of His Ever-Blessed Mother,

humbly desiring to make this foundation to Their honor and in memory of the aforesaid favors.

It appears to have been in this

church that the celebrated image of Our Lady was preserved to which St. Thomas More alludes in one of his letters, when praising the

affability of King Henry VIII he says, He is so courteous to all that everyone may find somewhat whereby he may imagine that he loves

him; even as do the citizens' wives of London who think that Our Lady's image near the Tower doth smile on them as they pray before it.

The instances here given of vows made by our Plantagenet kings in consequence of deliverances attributed to the intercession of the

Blessed Virgin might be largely multiplied. Not only Oriel College, Oxford, but the Carmelite convent in the same city, was founded

by Edward II, in consequence of a vow made when escaping at the peril of his life from the field of Bannockburn. The devotion of

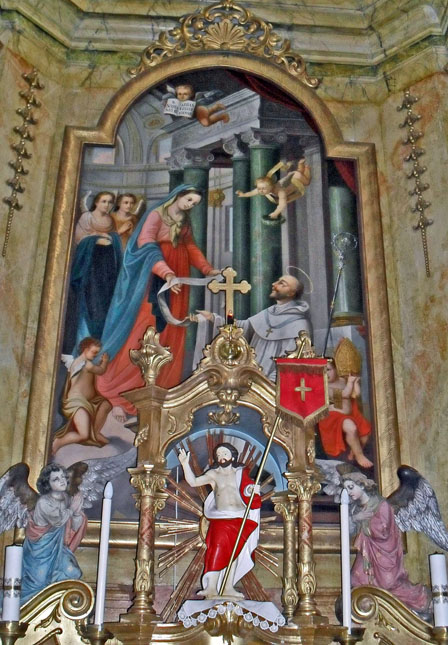

Richard Coeur de Lion (Richard I the Lionheart, image right) to the Blessed Virgin was chiefly shown by his donation to Her sanctuaries in

Normandy, in thanksgiving for numberless graces. One of them is related by Roger Hovedon, who says that during the siege of Acre,

Our Lady appeared to certain sentinels in the Crusade camp, and bade them tell the kings of France and England that they might cease

the battering of the walls, for that on the fourth day they should be in possession of the town, which came to pass just as had been

promised. Richard's great victory gained over the Turks by the river Rochetaile on the eve of Our Lady's Nativity, was likewise

regarded as obtained through Her intercession. The Abbey of Westminster contained a celebrated image of Our Lady, very much esteemed

by the Plantagenets, of which Froissart says that

The instances here given of vows made by our Plantagenet kings in consequence of deliverances attributed to the intercession of the

Blessed Virgin might be largely multiplied. Not only Oriel College, Oxford, but the Carmelite convent in the same city, was founded

by Edward II, in consequence of a vow made when escaping at the peril of his life from the field of Bannockburn. The devotion of

Richard Coeur de Lion (Richard I the Lionheart, image right) to the Blessed Virgin was chiefly shown by his donation to Her sanctuaries in

Normandy, in thanksgiving for numberless graces. One of them is related by Roger Hovedon, who says that during the siege of Acre,

Our Lady appeared to certain sentinels in the Crusade camp, and bade them tell the kings of France and England that they might cease

the battering of the walls, for that on the fourth day they should be in possession of the town, which came to pass just as had been

promised. Richard's great victory gained over the Turks by the river Rochetaile on the eve of Our Lady's Nativity, was likewise

regarded as obtained through Her intercession. The Abbey of Westminster contained a celebrated image of Our Lady, very much esteemed

by the Plantagenets, of which Froissart says that it worked many fine miracles.

It was before this image that Richard II prayed

on the day that he rode to Smithfield to meet Wat Tyler and the rebellious commons.

We may also note Hailes Abbey in Gloucestershire, founded under similar circumstances by Richard Earl of Cornwall and

King of the Romans, and dedicated to Our Lady in fulfillment of a vow made during a tempest at sea. This Abbey was rendered famous

by the gift of a relic of the Precious Blood placed here by Edmund, son and heir of Earl Richard. And in connection with these stories

of deliverances from shipwreck may be given an anecdote which occurs in the manuscript history of Dieulacres Abbey in Staffordshire.

This Cistercian Abbey was founded in 1214 by Randal Earl of Chester, who soon after returning from the Holy Land, where he had performed

many glorious deeds, was overtaken by a storm, and in great danger of perishing. In the midst of their distress, he asked the sailors

what time it was, and they replying that it wanted about two hours before midnight, he made them work on with courage for those two hours,

saying that he had a confident hope the storm would then abate. Far from abating however, it grew worse, and at last the pilot said,

Sir, commend your soul to God, for the tempest increases and we can scarce any longer hold the oars.

Then the Earl arose and

began with all his might to help with the oars and sails, and soon after the weather became calm. The next day, the captain of the

ship begged the Earl to tell them why he had desired them to work on during those two hours, and why he had afterwards helped them

himself more than anyone else who had been on the ship. It was,

he replied, because I knew that at midnight my monks,

and those whom my ancestors also had founded in divers places, would arise to sing the divine office, and therefore I had confidence

in their prayers, and trusted right well that God through their suffrages would give me a strength at that hour which I did not possess

before.

The last illustration of our subject which I shall draw from the Cistercian annals, belongs to a period subsequent to

the Protestant reformation,

but the circumstance, occurring as it did, in an age little sensible to the instincts of faith,

is only the more deserving of credence.

Nicholas Fagan, an Irishman by birth, took the habit of religion in the famous Cistercian Abbey of Ferrara in Castile in the latter part of Queen Elizabeth's reign. After some years he was sent back to Ireland, where, though exposed to many dangers and more than once beaten, ill-used, and wounded by his enemies, he nevertheless managed to preserve his life, which he spent in apostolic labors. He was very desirous of promoting the devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary as a powerful means of restoring and strengthening the Catholic Faith, and for this purpose he placed an image of Our Lady (see home page) which he had brought with him from Seville in an oratory attached to the hospital of St. John in the city of Waterford, where numerous Catholics devoutly resorted, in whose behalf, says Don Gaspar Jongelino (in his work entitled the Porpora di S. Bernardo), Our Lord, through the intercession of His Blessed Mother, worked many and astounding miracles. There was a certain man who lived in the county of Kilkenny, whose arm had been withered from his birth, so that he could not so much as move it. One night the Mother of God appeared to him, and commanded him to go to Waterford and visit Her image preserved in St. John's Hospital, promising him if he did so, the restoration of his arm. On awaking he resolved to obey what he believed to be a Divine revelation, and setting out the same day for Waterford, he acquainted Father Fagan with the reason of his visit. The good father bade him wait till the next day, when he would say Mass and recommend his cure to God. In the morning a considerable number of Catholics assembled in the oratory where Father Fagan said Mass, and at the moment of the elevation, the man felt his arm suddenly and perfectly restored, so that he at once used it by fervently striking his breast. Not wishing, however, to cause any disturbance at that moment by declaring what had happened, he held his peace till the end of Mass, when he raised his arm now as healthy and whole as the other, and proclaimed his cure to all present.

Another miracle, of a somewhat different character, yet further increased the veneration of Catholics for this holy image, which they visited in such throngs that the little oratory was never without some pious votary. A certain Catholic of the neighborhood who retained the Faith, but unhappily followed a very disorderly life, had stolen some necklaces of great value, but not so secretly as to escape suspicion. He was accused of the crime, but swore to his innocence, and the fact was not proved against him. In company with several persons who had been present when he took the false oath, he went to hear Mass in St. John's oratory before the holy image. In the midst of the Mass the necklaces fell at his feet, without anyone perceiving from whence they came. The thief finding himself detected, fell on his knees, and confessed his crime, receiving a severe reproof from the venerable servant of God.

Nicholas Fagan was afterwards elected Bishop of Waterford, but died in 1616, before receiving Consecration. His tomb

is still to be seen in the Church of Waterford bearing an inscription in Latin verse, and his memory is commemorated in the Cistercian

Menology on March 8.

Nicholas Fagan was afterwards elected Bishop of Waterford, but died in 1616, before receiving Consecration. His tomb

is still to be seen in the Church of Waterford bearing an inscription in Latin verse, and his memory is commemorated in the Cistercian

Menology on March 8.

The Premonstratensian Order was introduced into England about the same time with the Cistercian, and like it, claimed in a very special way to be under the patronage of the Blessed Virgin, from whose hands St. Norbert was said to have received the white habit (image right). By far the greater number of its monasteries were dedicated in Her honor, and in the histories of their early foundation we frequently meet with legends of a similar nature to those already quoted. Certain localities were believed to have been selected by Our Lady for Her own sanctuaries, and among these was the valley known as Depedale, in Derbyshire, where afterwards arose the Premonstratensian abbey known as Dale Abbey or Stanley Park.

The circumstances of its early history are thus related. There lived in Derby, in the street that bore Our Lady's name,

a certain miller named Cornelius, who was accustomed every Saturday to bring to St. Mary's parish church all the money he had earned,

except what was absolutely necessary for his maintenance, and there to distribute it to the poor for the love of God and Our Lady.

He persevered in this laudable habit for many years, and at last one day in autumn as he was taking some rest at midday, the Blessed

Virgin appeared to him in his sleep, and said to him, Cornelius, My Son has accepted thine alms. But if thou wouldst be perfect

leave all that thou hast, and go to Depedale and there serve Me and My Son in a solitary life, and when thy course is ended thou shalt

be admitted to eternal joys.

Awaking from slumber Cornelius gave thanks to God and Our Lady, and saying nothing to any man,

prepared without delay to obey the heavenly vision. He set out, not knowing where Depedale was, but confident in the divine guidance.

And taking his way towards the east, as he passed through the village of Stanley he heard a woman say to her daughter, Take our cows

and drive them to Depedale, and make haste home again.

Full of wonder, he approached the woman saying, I pray thee, good woman,

tell me where Depedale is.

Go with the girl, if you will,

she replied, and she will show you the way.

He followed

the girl therefore, and her cows, till they came to a certain solitary valley covered with forest and far from all human habitation,

where finding out a sheltered spot, he scooped for himself out of the rock a little hermitage (image below) wherein he made

himself an altar, and there served God in hunger and thirst, cold, and the want of all things.

The lands round about belonged to Ralph FitzGeremund, who had lately returned into England from Normandy, and visiting the neighborhood came to this valley one day with his dogs seeking for game, and perceiving smoke rising out of the good hermit's cave, he was filled with indignation and wonder that any man should presume to make himself a habitation in his forest. Going to the spot, therefore, he found Cornelius clad in old ragged garments, and his heart was touched with compunction, so that having heard who he was and the story of his coming thither, he not only freely gave him leave to remain but granted him the tenth of the produce of his mills for his support. The history goes on to relate the many combats which the hermit had afterwards to sustain from the ghostly enemy, and how eventually he removed to another part of the same valley near a spring of water, and there built himself a hut, and an oratory dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary wherein he some years afterwards happily passed to the Lord. The oratory of St. Mary's was afterwards given to some black canons, and finally William FitzRauf and his daughter Matilda bestowed the valley and its appurtenances on a colony of Premonstratensians in the year 1204.

Two more of these monastic legends shall be added, of which the first carries us back to the days of the crusaders.

Shortly after the Norman Conquest the lands of Wroxall in Warwickshire were held by Richard, Lord of Hatton, whose son Sir Hugh was

a man of great stature and valor, and took part in the first crusade wherein the Holy Land was conquered by Christian people out of

heathen men's domination by sore wars.

In this war Sir Hugh was taken prisoner and kept by the heathen people with great hardship

for seven years, till at last weary of his tribulations he reminded himself that his parish church in England was dedicated to

St. Leonard, and calling to mind the many miracles wrought by that holy confessor, he made his complaint full piteously to him,

laying before him how in his youth he had ever had great devotion to him, and on his feast had fed both poor and rich, and beseeching

him to come to his aid now that he was taken prisoner in the cause of God. In his sleep St. Leonard appeared to him clad in the habit

of a black monk, and bade him rise and go home and found a place for nuns of St. Benedict's Order. And soon after he appeared to him

a second time not in his sleep but when awake, whereat the knight joyful with weeping and spiritual gladness vowed to fulfill the Saint's

behest; and suddenly found himself with his chains set down in Wroxhall Wood, at the east end of what was afterwards the chancel of the

church, fast by his own manor. He did not at first know where he was, and as it happened there came by one of his own shepherds,

and for the grisly sight of him the man was sore feared and charged him in God’s name to tell him what he was.

The knight,

greatly comforted to hear the English speech, said he was truly a man, and asking where he was, marveled to find that he was on his

own land. Then he enquired concerning his wife and children and heard what alms and prayers were done daily for his release,

and that many vows had been offered to Our Lady and other Saints. Then heartily thanking God, Our Lady, and St. Leonard, the knight

bade the man bring the lady hither with her children. She accordingly came to the spot and on first seeing him, knew him not, but

feared for the grisly sight of him.

But he drew out half a ring, and reminded her how on their parting they had broken that

ring together; and each kept a part, and when the two parts were brought together again they exactly joined.

The lady, recognizing him at last to be indeed her lost husband, swooned for joy. Then they loosed him from his chains

and so proceeded to the church; where after giving thanks to God, Our Lady, and St. Leonard, Sir Hugh declared his vow, and his purpose

to fulfill it. Desiring to know from God where the church should be built, it is added that stones without man's hand were pitched

on the ground,

and the altar stood on the spot where he was first discovered. The ring before spoken of was still preserved among

the relics at the time when the writer of this account was living, together with a portion of Sir Hugh’s chains, the rest having been

put into the bells. The founder's two daughters, Edith and Cleopatra, were the first nuns, a lady from the house of Wilton

coming to instruct them in the religious life.

To the foundation of the Lady Chapel belonging to this church is attached a legend no less miraculous than that which

we have just related. Dame Alice Craft, one of the nuns, poor of worldly goods but rich in virtues,

desired greatly that she

might live to see a chapel built here to Our Lady. To that intent she ofttimes prayed; and one night there came a voice to her,

bidding her in the name of God and Our Lady to begin and perform Our Lady’s chapel.

She thought it but a dream and took no heed

thereof, till the same charge was given her a second time, and more sharply. Then she awoke and fell into a great weeping,

not having wherewith to do it, and informed her prioress, who treated the whole thing as an idle phantasy. But at last Our Lady Herself

appeared to Dame Alice, and blamed her so sharply for her negligence that in great fear she hastened to her prioress and entreated her

to believe the vision. The prioress, somewhat moved by her words, asked her how much she had towards it, and she replied fifteen pence.

Then,

said the prioress, though it be little, Our Lady may full well increase it,

and so she gave her leave to begin.

Then this Dame Alice gave herself to prayers, and besought Our Lady to give her knowledge where she should build it

and how large she should make it. Then she was told by revelation to make it on the north side of the church, where she should find

the size marked out. This was in harvest-time, between the two feasts of Our Lady (that is, between the Assumption and the Nativity);

and on the morrow early, she went into the place assigned to her, and there she found a certain space of ground covered with snow;

and there the snow abode from four o’clock in the morning until noon. She, glad of this, had masons ready, and marked out the ground,

and built the chapel and performed it up. And every Saturday whilst it was in building she would say her prayers in the alleys of the

churchyard, and in the plain path she found, weekly, silver sufficient to pay her workmen and all that was required to her work,

and no more.

This good nun, Dame Alice Craft, adds the narrator, died on the seventh of the calends of February on the morrow

after the Conversion of St. Paul,

and lies buried under a stone in the same chapel, before the door leading into her choir.

She was, he says, a woman of great stature, as beseeming of her bones.

(The above quotations are from a history printed in

Dugdale's Monasticon, from a manuscript assumed to have been written about the time of Edward VI.)

The other story referred to is also attached to the foundation of an English nunnery, that of Godstow in Oxfordshire,

which owed its construction to the following circumstances, as related in the book of the register. In the reign of King Henry I,

a certain devout widow of Winchester named Editha was ofttimes warned in a vision to go to the neighborhood of Oxford and abide there

until such time as a sign should be given her from God, in what wise she should build a house for His service. She accordingly chose

the village of Binsey, then a very famous place of devotion, both as having an image of St. Frideswide (pictured on stained glass,

image below), to which much pilgrimage was made, as also for the Holy Well of St. Margaret. So great was the throng of pious

visitors, that twenty-four inns for their accommodation were erected at Seckworth on the opposite side of the river, and a great number

of priests were stationed there to hear the confessions of the pilgrims. Here therefore Editha took up her residence,and much holy

life she led,

until one night she heard a voice which said to her, Editha, arise and, without hesitating, go ye there where the

light of Heaven alighteth to the earth from the firmament, and there select nuns to the service of God, twenty-four of the most

gentlewomen that ye shall find.

The spot indicated by this miraculous sign was situated on the river Isis, about two miles from Oxford, in the near vicinity of Binsey, and here Editha in 1138 built her Church and Convent of Godstow, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist. King Stephen and his Queen assisted at the consecration, and an indulgence of forty days was granted to all those who would devoutly visit the Church on the feasts of the Blessed Virgin or St. John.

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com