A. A Sacrament is an outward sign by which grace is communicated to the soul, instituted by Jesus Christ,

and consisting of two elements – matter and form.

A. A Sacrament is an outward sign by which grace is communicated to the soul, instituted by Jesus Christ,

and consisting of two elements – matter and form. A. A Sacrament is an outward sign by which grace is communicated to the soul, instituted by Jesus Christ,

and consisting of two elements – matter and form.

A. A Sacrament is an outward sign by which grace is communicated to the soul, instituted by Jesus Christ,

and consisting of two elements – matter and form.

Besides our own good works, which, by God's grace, are profitable for salvation, God has given us two powerful means of salvation – prayer and the Sacraments. Prayer obtains grace by humble petition; the Sacraments effect grace by their own virtue. Prayer obtains graces of all kinds; the Sacraments, besides sanctifying grace or its increase, confer special graces for special ends.

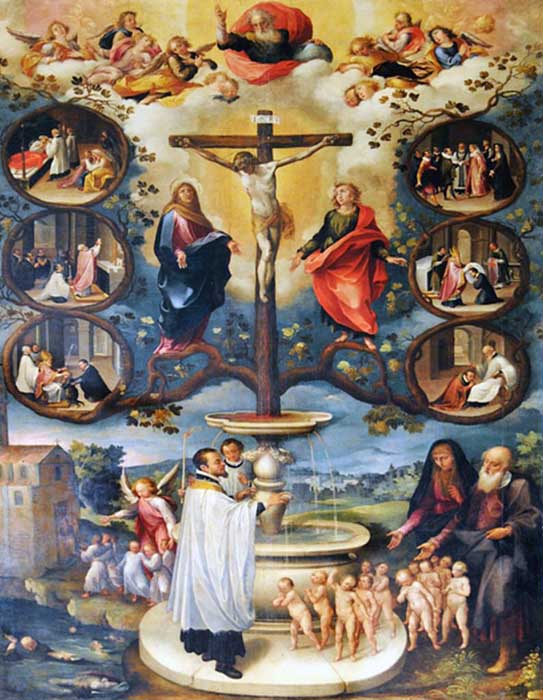

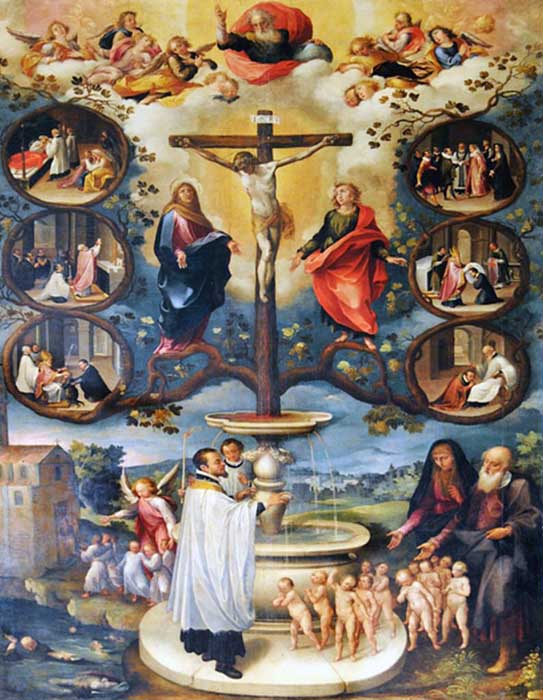

I. A Sacrament is an outward or visible (sensible) sign instituted by Christ by which invisible grace is imparted to the soul. Therefore any sacred rite or ceremony possessing these three characteristics is a Sacrament.

1. A sign in general is anything by which we can recognize an object. There are two kinds of signs: indicative and effective. An indicative sign supposes the existence of the object which it signifies: an effective sign produces its object. Thus thunder is an indicative sign of lightning, a dark cloud is the effective sign of rain. The Sacraments are effective signs, viz., they produce of themselves, not in virtue of the disposition of the recipient, the grace which they signify.

2. Invisible grace is the object signified and effected by these signs. Grace is to be understood here in its strictest sense, i.e., as that which renders the subject pleasing to God. For, though some of the Sacraments confer a permanent character on the recipient (Baptism, Confirmation, Holy Orders), and are some-times attended by gratuitous gifts, yet their essential and ordinary effect is grace strictly so-called.

3. The institution by Christ is essential to a Sacrament, since God alone can attach invisible grace to a visible sign. A visible rite by which Christ Himself would confer grace would not be a Sacrament unless He had made it a permanent institution in His Church. The rite, for instance, by which He forgave St. Mary Magdalene her sins was not a Sacrament.

II. This outward sign is composed of two elements, matter and form; for matter alone, e.g., water, as St. Augustine (tract. 80 in Joan. n. 3) remarks, is not a sufficiently expressive sign without some form of words.

In visible bodies philosophers distinguish an indefinite and a defining or differentiating element. The former is called matter, the latter form. Thus metal (matter), for instance, is defined or shaped into a certain instrument by a given form. This notion of matter and form is applicable to visible signs. An action or movement of the hand, for instance, may mean anything of itself; but if it is accompanied with words all uncertainty vanishes and the sign becomes intelligible. Hence the words which give full signification to the action are called the form; the action, which is in itself indefinite, is called the matter. Thus the sprinkling with water might signify purification or refreshment; the form which is added in Baptism makes it signify the cleansing from sin. Matter is remote or proximate according as we consider it in itself or in its actual application. Thus water in itself is the remote, the pouring of water the proximate, matter of Baptism.

From the matter and form of the Sacraments are to be distinguished the ceremonies attached – certain symbolic actions some of which have Christ Himself as their Author, while others have been instituted by the Apostles, and others again by the Church. Their object is to represent more forcibly to us the dignity of the Sacrament, to give suitable expression to the devotion of the minister, and to give edification to the faithful.

B. The Sacraments are productive of two kinds of grace – sanctifying and sacramental – and that by their own inherent virtue (ex opere operato).

Among the reformers of the sixteenth century some asserted with Luther that the Sacraments were only a pledge or sign of the remission of sins already received, or a means of fostering faith; others contended with Zwingli that they were only a profession of faith; while others, again, held with Calvin that they conferred grace, but on the predestined only. All these opinions are opposed to Catholic teaching.

I. The Sacraments not only signify, but effect grace. They are effective signs of grace; yet they are

more properly called signs than causes of grace, because a sign means something visible, and has a certain visible

resemblance with an invisible thing. (a) In regard to Baptism we read: Be baptized every one of you for the

remission of your sins

(Acts 2: 38). Now, if Baptism remits sins it is not merely an indicative sign,

but an effective one. The same holds of the other Sacraments, since they resemble Baptism in their effects.

(b) The Church, in accordance with Scripture and tradition, teaches that the Sacraments contain and confer

grace upon those who receive them worthily

(Florent. decret. pro Armen.);

that they always confer grace on those who do not oppose an obstacle in their way

(Trid. Sess. VII de sac. in gen. can. 6, 7).

God's wisdom is strikingly manifested by the attachment of grace to visible signs. (a) Since man derives his knowledge from the senses, sensible things are in the supernatural order a means of leading him to God. (b) Christianity itself is founded on sensible facts – on the incarnation of the Son of God and His death on the Cross. Therefore it was meet that visible channels should also convey the graces that flow from these visible sources. (c) A closer union is thus effected between the members of the Church by the same visible channels, as they receive their faith from the visible teaching authority of the Church. (d) By the fact that visible elements are means of grace we are, on the other hand, humbled by our dependence on inanimate things, but, on the other hand, reassured and consoled by the possession of a visible pledge of divine grace. (e) Visible creation is ennobled by the elevation of inanimate elements to a supernatural efficacy.

II. The Sacraments effect a twofold grace: sanctifying grace and special actual graces, called sacramental grace.

Sanctifying grace is conferred by the Sacraments if it does not already exist; if it already exists it is increased. In the former case it is called first grace, in the latter, second grace; though in both cases it is the same in substance. With sanctifying grace is given the right to special actual graces which enable the recipient to obtain the end for which the Sacrament was instituted. This actual, or sacramental, grace is given according as circumstances demand, not merely at the time of the reception of the Sacrament.

Jesus instructs the Samaritan woman. Actual grace enlightens the mind...

a. That those Sacraments which produce the supernatural life in the soul confer sanctifying grace is manifest,

since the supernatural life itself consists in sanctifying grace. But the other Sacraments also increase, and therefore confer,

sanctifying grace. They confer the fruits of sanctifying grace. Thus, for instance, Holy Orders, according to the Apostle,

confer the spirit of power, of love, and of sobriety

(2 Tim. 1: 7). Since, therefore, they confer the fruits or

effects of sanctifying grace, we must conclude that the root and foundation – sanctifying grace itself – is likewise conferred

or augmented. Together with sanctifying grace the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity are also either infused or increased;

for these virtues complete man's supernatural likeness to God by giving him the habit or facility of performing supernatural works.

b. From the connection between the external sign and the thing signified it follows that the Sacraments confer also special sacramental graces. They would be mere empty signs unless they effected what they signify. But actual grace alone, or such a supernatural aid given as circumstances require, enables man to attain the supernatural end for which the Sacraments have been instituted. Hence the Sacraments must also confer sacramental grace, or those special actual graces which they signify.

III. The Sacraments effect grace by their own inherent power (ex opere operato) in virtue of the sacramental act itself, not in virtue of the acts or disposition of the recipient, or of the worthiness of the minister (ex opere operantis). The sacramental rite itself is the cause of grace.

Such efficacy is implied (a) in the words: Unless a man be born again of water and of the Holy Ghost,

etc. (John 3: 5). Here regeneration is attributed to the act of Baptism itself, although the adult by a due

preparation must dispose himself in order to become a suitable subject for such efficacy. (b) If it were not the Sacrament

itself, but the disposition of the recipient or of the minister, that produces grace, infants, who have not the use of reason,

could not receive the grace of Baptism, and that independently of the disposition of the minister.

Therefore Baptism effects grace ex opere operato. (c) It has always been the universally received doctrine of the Church

that the Sacraments effect grace by their own power in those who put no obstacle in the way. This truth was variously

emphasized and expressly defined by the Council of Trent (Sess. VII, de sac. in gen. can. 8).

The Sacraments are, therefore, not mere conditions under which God effects grace in the soul – as, for instance, a window is the condition, not the cause, why a room is lighted; they are truly means or causes effecting grace in the soul. They possess this efficacy as means instituted by Christ to communicate the fruits of His Passion.

C. The Sacraments of the New Law have a different efficacy from those of the Old, and from the sacramentals

of the Church.

C. The Sacraments of the New Law have a different efficacy from those of the Old, and from the sacramentals

of the Church.

I. By the Sacraments of the Old Law we understand those rites whose object was the sanctification of the faithful. Among them were the various rites of purification, and particularly circumcision. The sanctification conferred by them was not internal, but merely external or legal. They were a sign of the union of the recipient with God's people, and a testimony of his obedience to the law. The Old Covenant is characterized in Scripture not as a dispensation of grace, but as the law (John 1: 17); not as freedom, but as bondage; not as the spirit that gives life, but as the letter that killeth (2 Cor. 3: 6). Now, it could not thus be characterized if its sacraments conferred grace as in the New Law. Hence the Council of Florence (Decret. pro Armen.) teaches that the sacraments of the Old Law did not effect grace, but only prefigured that grace which was to be given through the Passion of Christ. They were a figure of the Sacraments of the New Law as the Old Law itself was a figure of the New.

The internal grace received by the partakers of the sacraments of the Old Law was, therefore, not effected ex opere operato, but ex opere operantis. In adults perfect charity as well as faith was necessary for justification. For the justification of infants the faith of those who by any rite consecrated them to God was sufficient. This arbitrary rite – commonly called by divines the sacrament of nature – was a condition under which God conferred on them the grace of justification, not the cause or means of justification. Even the rite of circumcision instituted by God Himself for the dedication of male children was not of itself productive of grace; for God instituted it not as a means of grace, but as an external sign of His covenant with His people. It served as a profession of faith for the attainment of justification. Hence the sacraments of the Old Law were not be compared in dignity with those of the New, which in virtue of their divine institution are true means of grace.

II. Sacramentals are certain means employed by the Church to obtain graces and temporal favors. They are either blessed objects (holy water, oil, salt, etc.) or certain rites or ceremonies (e.g., exorcisms, blessings). The Church in its benedictions prays that God, Who is wont to make use of external objects to communicate His gifts, may by these means bestow His graces and favors upon us. Thus sacramentals have, as their name implies, a certain resemblance to the Sacraments. But their efficacy differs from that of the Sacraments chiefly in this – that while the Sacraments in virtue of their divine institution, if duly administered and worthily received, have an infallible effect (ex opere operato) the sacramentals, on the other hand, do not operate of their own power, but only in virtue of the prayers of the Church (ex opere operantis).

D. On the part of the recipient of the Sacraments certain conditions or dispositions are necessary in order that the reception may be valid, and due preparation that it may be fruitful.

I. Certain conditions are necessary for the valid reception. (a) one must be still in the state of probation here on earth (i.e., still alive): for the Sacraments are a means of salvation, and, consequently, only for those who are still on the way to salvation, not for those who have finished their pilgrimage. (b) Baptism is a necessary condition for the valid reception of the other Sacraments. The Sacraments are instituted only for those who belong to the visible body of the Church; but by Baptism alone we become members of the Church. Moreover, the other Sacraments are instituted either to increase or to restore the supernatural life of the soul. But it can neither be increased nor restored unless it has been once conferred; but the supernatural life is ordinarily conferred in Baptism. (c) In the case of adults, moreover, the intention of receiving the Sacraments is necessary. For, since rational man can be saved only by his own will, the means of salvation cannot be applied to him unless he choose to accept them. Therefore Baptism administered to one against his will would not be a Sacrament. In the case of children and idiots such an intention is not required, as is manifest from the practice of the Church in administering certain Sacraments to them.

II. Certain preparations are, moreover, required that the reception of the Sacraments may be worthy and fruitful. Despite the validity of a Sacrament its effects may be completely or partly frustrated either by the existence of some obstacle or by the absence of that disposition which renders the soul capable of receiving grace. Now, preparation is necessary to remove such obstacles, or to produce such disposition. The necessity of preparation follows, moreover, from the necessity of preparation for justification in general. We must ourselves cooperate in the work of our salvation, and render ourselves susceptible of the influence of grace.

E. On the part of the minister of the Sacraments certain conditions are necessary in order that their administration may be valid and licit.

I. For the valid administration of a Sacrament is required in the minister the intention to do what the Church does (Florent. decret. pro Armen.) The form of the Sacrament is not only significant, but also effective. But it cannot be effective without the proper intention. A priest, for instance, who incidentally, and without intending to consecrate, pronounces the words of Consecration in the presence of bread and wine does not thereby consummate the Sacrament. But if, on the other hand, the minister intends to do what the Church does by that rite, or to perform the sacred function in accordance with the usage of the Church, he has, as a matter of course, the intention that the rite should have its full efficacy, and, therefore, validly performs the Sacrament.

For the valid administration of a Sacrament neither sanctity, nor virtue, nor even faith, is necessary on the part of the minister. The Donatists in the fourth century required positive worthiness, and certain Asiatic and African bishops in the third century required at least faith in the minister. But both these opinions were condemned by the Church as heretical; and justly, for man does not administer the Sacraments by his own power, but by the power of Christ, Whose instrument he is. But he becomes the instrument of Christ by the sole intention to do what the Church does.

II. For the licit administration of a Sacrament it is required that the minister should be in the state of grace. For, if holy things are to be treated holily, this is most emphatically the case in regard to the Sacraments, which are the means of applying to us the merits of Christ Crucified. Moreover, the minister of the Sacraments represents the Person of Christ, and is His instrument; but he cannot fitly and worthily represent Christ or be His instrument if he is in the state of mortal sin.

Hence it is lawful only in the case of extreme necessity (i.e., danger of death) to use the ministry of a priest who is notoriously unworthy, particularly if he is suspended, deposed, or excommunicated.

F. Christ instituted seven Sacraments.

I. That there are seven, and only seven, Sacraments instituted by Christ has been declared by the Council of Trent (Sess. VII de sac. in gen. can. 1) against the heretics of the sixteenth century, who admitted – some only two Sacraments (Baptism and Holy Eucharist), others three (including Penance). The Council of Florence (Decret. pro Armen.) had already defined the number of the Sacraments.

II. It is certain that the doctrine of the seven Sacraments was universal in the Church in the twelfth century;

for from that time we possess full treatises upon each of the seven. Moreover, it is certain that even at an earlier date those

very Sacraments which were rejected by the reformers

had been considered true Sacraments. Synods of the seventh century

(e.g., that of Rheims, ca. 630) issued directions for their administration. Hence it follows that this doctrine is handed down

from apostolic times; for it would have been impossible to introduce innovations in a matter of such importance without great opposition;

of which, doubtless, some mention would be found in history.

III. It is no less certain that those Oriental sects who fell off from the Church in the earliest times hold the dogma of the seven Sacraments. Whence we must infer that at the time of their separation this doctrine prevailed in the Church, as they certainly would not have subsequently accepted it from the Church.

God could have instituted fewer or more Sacraments. However, certain reasons may be assigned why He instituted precisely these seven; for these are sufficient for the existence and continuance of supernatural life. (a) Baptism, the Sacrament of regeneration, was instituted to confer the spiritual life itself together with those supernatural faculties necessary for its functions, just as natural generation confers on us our natural life and its faculties. (b) Confirmation strengthens the spiritual life and bestows fortitude and perseverance in the spiritual combat. (c) The Holy Eucharist supplies the spiritual nutriment which is necessary to sustain our supernatural life. (d) Penance restores the supernatural life, if lost by sin. (e) Extreme Unction heals the soul from the effects of sin and gives strength and consolation in the last struggle. (f) Holy Orders enable the ministers of Christ’s Church to discharge their duties worthily, and through them secures for the faithful those spiritual treasures committed by Christ to His Church. (g) Matrimony brings God's blessing upon the marriage union, to enable parents to bring up their children for the Kingdom of God.

All the seven Sacraments, as the Church teaches (Trid. Sess. VII de sac. in gen. can. 1), were instituted by Christ. For the rest, it is evident that God alone can attach invisible grace to a visible sign. Christ, moreover, instituted the Sacraments directly, not through His Apostles; for the Apostles are the dispensers, not the authors, of the mysteries of God (1 Cor. 4: 1).

G. The Sacraments are divided (1) into Sacraments of the living and of the dead; (2) into such as imprint, and such as do not imprint, a character on the soul of the recipient.

I. The Sacraments are divided, according to the disposition required in the recipient, into Sacraments of the living and of the dead. Baptism and Penance are Sacraments of the dead, because they may be received by those who are spiritually dead by mortal sin. If the person who receives them is already in the state of grace they increase the supernatural life already existing. The Sacraments of the living are those which presuppose the existence of the supernatural life in the soul, and whose object is to increase it. Such are Confirmation, Holy Eucharist, Extreme Unction, Holy Orders, and Matrimony.

The Sacraments of the living, however, may, according to the common opinion of theologians, in some cases confer sanctifying grace itself, or first grace – as, for instance, in the case of one who believes himself to be in the state of grace, but really is not, and receives one of those Sacraments with only imperfect contrition. His imperfect contrition will in that case remove the obstacle to the efficacy of the Sacrament, which will, consequently, produce its effect – sanctifying grace.

II. Certain Sacraments cannot be repeated, while others may be received more than once. The former are Baptism, Confirmation, and Holy Orders. The reason why these cannot be repeated is, as the Council of Trent (Sess. VII de sac. in gen. can. 9) and the Council of Florence (decret. pro Armen.) teach, because they imprint a permanent and indelible character upon the soul. This mark confers upon the recipient a special dignity, as well as the power to exercise the functions peculiar to that dignity. In Baptism we become members of Christ's Kingdom; by Confirmation soldiers of Christ; by Holy Orders leaders of Christ's followers. The fathers speak of the Sacraments above mentioned as imprinting a seal upon the soul (cf. S. Aug. tract. in Joan. n. 16). This seal is indelible, and continues to exist not only during this life, but also after death, to the glory of the blessed and the confusion of the reprobate.

If we consider the Sacraments according to their necessity, we find that Baptism is necessary for all, Penance for those who after Baptism have fallen into grievous sin, and Holy Orders for the Church as such. In dignity, however, the Holy Eucharist surpasses all the others.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com