Celebrated Sanctuaries of the Madonna

Eighteenth in a Series

In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries

of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the

wily criticism of many Protestants.

Conclusion — Devotion to Mary from Antiquity

The examples which have been cited in the foregoing articles chiefly exhibit the devotion to Our Lady in either its

modern or its medieval aspect. But it would not be difficult to trace back the same devotion into far earlier ages, and present

the reader with illustrations gathered from the sixth, the fourth, or the second centuries, differing but little in their general

character from those with which we have hitherto been engaged. Not merely do the writings of the Fathers lay down those dogmas of

Faith which form the root and groundwork of our devotion to the Blessed Virgin, but history and tradition reveal to us the devotion

itself as practiced even in the desert and in the catacombs. However far we travel back we are met by facts and legends attesting

the universal belief in the power of Our Lady's intercession, and this power is represented as often miraculously displayed.

The annals of the Eastern Empire are as rich in such narratives as those of Western Christendom; and a few examples may be selected

from the first six centuries as best showing the identity of the ancient with the modern devotion.

The examples which have been cited in the foregoing articles chiefly exhibit the devotion to Our Lady in either its

modern or its medieval aspect. But it would not be difficult to trace back the same devotion into far earlier ages, and present

the reader with illustrations gathered from the sixth, the fourth, or the second centuries, differing but little in their general

character from those with which we have hitherto been engaged. Not merely do the writings of the Fathers lay down those dogmas of

Faith which form the root and groundwork of our devotion to the Blessed Virgin, but history and tradition reveal to us the devotion

itself as practiced even in the desert and in the catacombs. However far we travel back we are met by facts and legends attesting

the universal belief in the power of Our Lady's intercession, and this power is represented as often miraculously displayed.

The annals of the Eastern Empire are as rich in such narratives as those of Western Christendom; and a few examples may be selected

from the first six centuries as best showing the identity of the ancient with the modern devotion.

Thus, Evagrius in his Ecclesiastical History, speaking of the expedition of Narses into Italy in the year 552, tells us,

on the report of those who accompanied him in that campaign, that as he prayed, the Blessed Virgin appeared to him, prescribed the time

when he should attack the forces of Totila and desired him not gird himself for the battle until he had received a sign from Heaven.

This incident is noticed by Gibbon, and strange to say, without a sneer. The devotion of Narses to the Blessed Virgin was so well known

among his troops that when they celebrated his victories, they were accustomed to crown themselves with garlands and sing hymns in honor

of the Mother of God. And the sentiment which led them to ascribe their success to Her favor and intercession was equally shared by the

soldiers of his great contemporary Belisarius, whose conquest of the Arian Vandals of Africa was so commonly regarded as a grace obtained

from the hands of Mary, that the Emperor Justinian in token of his gratitude to Her erected three churches in Her honor at Leptis, Ceuta,

and Carthage.

The remarks made by Baronius on this subject are worthy of our notice. It seemed,

he says, as if the Blessed

Virgin and the Emperor Justinian engaged in a sort of contest which should be the most prodigal in the interchange of their good offices.

He defended Her against the attacks of the Nestorians who sought to deprive Her of Her supereminent title of the Mother of God,

and She advanced him to the imperial sovereignty; and because he erected numberless temples to Her honor, and particularly the

magnificent basilica in Jerusalem, it was given to him to subdue all Africa, for which benefit he showed his gratitude by the erection

of several other sanctuaries

(Baronius, An. 450).

Of Leo I, one of the worthiest of the Christian Emperors, a story is repeated by Nicephorus, to the effect that his future elevation

to the empire was made known to him when still a simple soldier, by Our Lady Herself, who appeared to him as he was charitably assisting

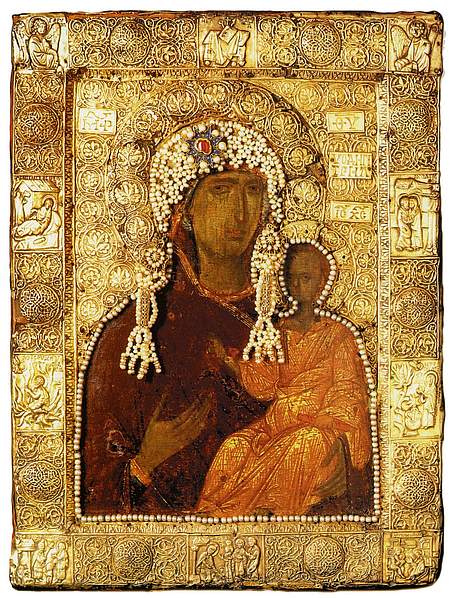

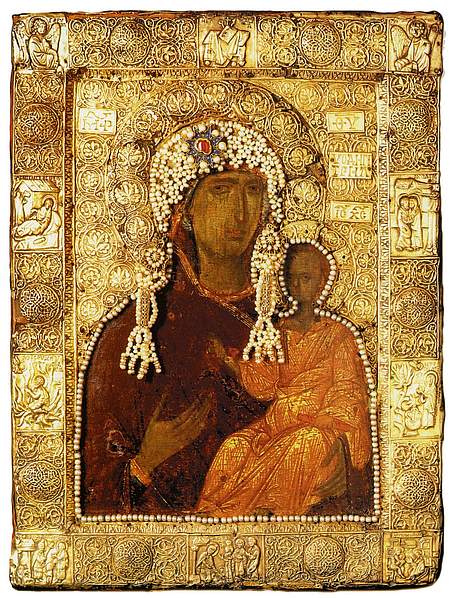

a poor blind man. The devotion of his predecessors, Marcian and St. Pulcheria, is spoken of by all historians. It was they who erected

the three great churches in Constantinople – the Chalcopratum, in which was preserved the girdle of Our Lady; in the Blaquerna, some

bands that had been wrapt around Her sacred body at Her entombment, and a picture, often borne before the emperors in processsions of

triumph; and in the Hodegus, another yet more celebrated picture, which was said to have been painted by Saint Luke, (above and

at left) and which had been sent to St. Pulcheria from Jerusalem by the Empress Eudoxia. It received the title of the Hodegetria,

and the custom became established for the Greek emperor to come here before setting out on any military expedition, in order to take

leave of Our Lady and ask Her blessing.

Of Leo I, one of the worthiest of the Christian Emperors, a story is repeated by Nicephorus, to the effect that his future elevation

to the empire was made known to him when still a simple soldier, by Our Lady Herself, who appeared to him as he was charitably assisting

a poor blind man. The devotion of his predecessors, Marcian and St. Pulcheria, is spoken of by all historians. It was they who erected

the three great churches in Constantinople – the Chalcopratum, in which was preserved the girdle of Our Lady; in the Blaquerna, some

bands that had been wrapt around Her sacred body at Her entombment, and a picture, often borne before the emperors in processsions of

triumph; and in the Hodegus, another yet more celebrated picture, which was said to have been painted by Saint Luke, (above and

at left) and which had been sent to St. Pulcheria from Jerusalem by the Empress Eudoxia. It received the title of the Hodegetria,

and the custom became established for the Greek emperor to come here before setting out on any military expedition, in order to take

leave of Our Lady and ask Her blessing.

In sieges the Hodegetria was often carried to the walls and deposited in those quarters most exposed to danger, and solemn thanksgivings

for any prosperous event were generally offered in this sanctuary. St. John Damascene, in one of his homilies, informs us that on the

occasion of the Council of Chalcedon in 451, St. Pulcheria applied to the prelates there assembled, and particularly to Bishop Juvenal

of Jerusalem, for relics of the Blessed Virgin Mary which she could deposit in these churches, and that Juvenal in his reply declared

that it was the true and constant tradition of the Church that He Who had been pleased to take flesh of Mary without prejudice to Her

virginity was pleased also after the death of that beloved Mother, to preserve Her immaculate body free from all corruption and to

transport it to Heaven.

We may summon the Emperor Julian the Apostate as a most trustworthy witness to the universality of this devotion among

the Christians of his time. It was one of his charges against them, that they ceased not to call Mary the Mother of God

(Jul. Op. t. 2, p. 159, 262). The death of this great oppressor of the Church is declared by St. Amphilochius

(the reputed author of the life of St. Basil that bears his name) to have been announced beforehand to that Saint by the mouth of

Our Lady. For as he prayed with all his people and clergy in a certain sanctuary dedicated to Her honor on Mount Didymus in Cappadocia,

and implored Her protection of the Church from the tyrant Julian, She appeared to him seated on a throne, and made known to him the

approaching death of the emperor, which took place shortly afterwards

[Fr. Northcote does not mention that in the vision, St. Basil saw Our Lady in Heaven, calling for the martyred

soldier St. Mercurius to go to the field of battle in which the Emperor Julian was engaged, and to slay him. In fact, Julian died

in the battle, wounded by an unknown soldier, who immediately disappeared. Just before death Julian exclaimed, Thou hast conquered,

Nazarene!

]

If we go back to the very foundation of the Christian empire we fnd Constantine immediately after the Council of Nicaea

dedicating his newly-founded capital (Constantinople, now Istanbul) to the Mother of God, as is related by more than one historian

(Niceph. l. vii. c. xxvi; Zonabres, Annal. l. iii). And when the basilica afterwards dedicated to Her was in course of building,

a story is preserved of Her appearing to the chief architect and directing him how to raise the enormous pillars that supported the roof.

Granting that the fact may be of no great authenticity, it shows that the belief in such apparitions was not strange to the Christians

of the time of Constantine.

If anecdotes of this sort are to be found scattered over the early annals of the Christian empire, they are no less

discoverable in the lives of the Saints belonging to the same period. The hermits of the East, it seems, were accustomed in the

sixth century to have in their cells images of the Blessed Virgin, before which they burnt lamps and candles. Thus Abbot John who

lived in a cave near Jerusalem, was accustomed when about to set out on a pilgrimage to the holy places, to address the Blessed Virgin

in the following terms: Holy Lady, Mother of God, since I am about to travel a long way, take care of my lamp, and do not let it be

extinguished, for I go trusting to have Thy help for a companion on my journey.

And the lamp, we are told, continued to burn

miraculously in his absence (Fr. Dalgairns' 'Lives of the Fathers of the Desert,' p. li). In another story a hermit is reproved

by Abbot Theodore, when tempted by the devil to put out of his cell the image of Our Lady and the Holy Child (Spiritual Meadow,

c. xlv. ed. Cologne, 1583. The editor, Lipoman, adds a note: This chapter was referenced and approved in the seventh Synod

[Nicaea II].

) In the same century flourished the famous St. Dorotheus and his disciple, St. Dositheus, the latter of whom

was converted to Christianity in a singular manner, when visiting the holy places of Jerusalem. He beheld there a certain image

representing the torments of Hell, and as he stood with his eyes riveted on it, he beheld at his side a Lady of majestic aspect with

a resplendent and beautiful countenance, who explained to him the eternal truths, and made known to him what rule of life he should

follow if he desired to escape those torments.

A somewhat amusing story is related thus by the Abbot Cyriacus in the Spiritual Meadow (c. xlvi).

On a certain day, he says, he beheld Our Lady, accompanied by St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, passing by the door

of his cell; and on his inviting Her to enter She refused, and regarding him with a severe countenance asked him why he kept Her

enemy concealed in his cell. In great distress and perplexity as to what this vision might mean, he took up a book which had

recently been given him by a priest of Jerusalem name Isychius, and found written at the end, one of the treatises of the heretic

Nestorius. At once understanding the riddle, he ran in all haste to Isychius with the book under his arm. Here,

he said, take

back your book; it has done me more harm than it will ever do me good.

And pray what harm has it done you?

asked Isychius.

Cyriacus related what had occurred. Is it so?

replied his friend, then I will have you to know that the enemy of Mary

shall not remain in my cell any more than in yours;

and with that he tore out the obnoxious treatise, and cast it into fire.

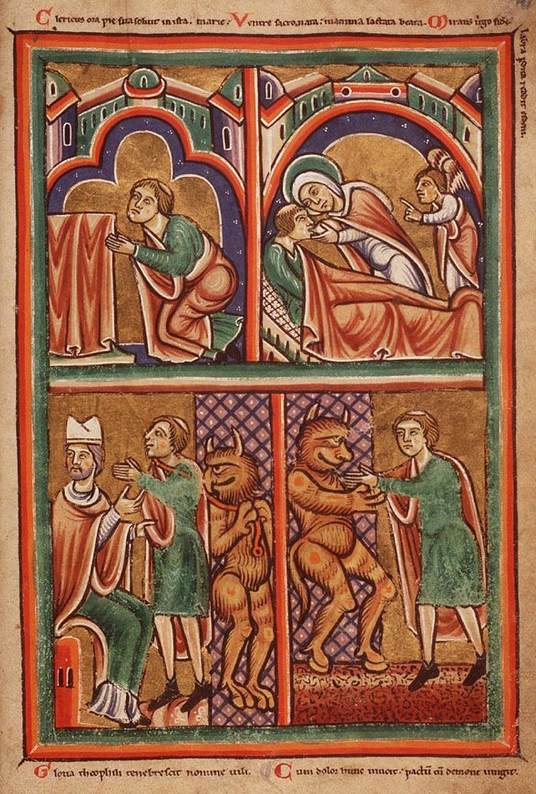

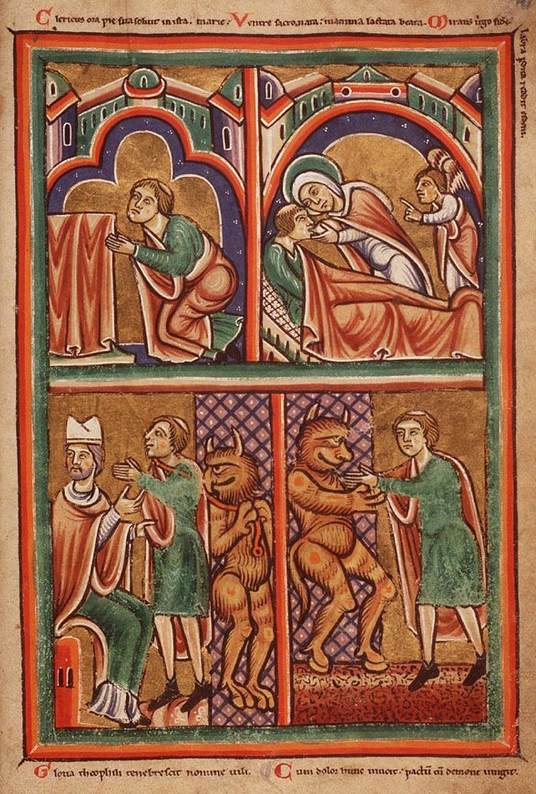

Two celebrated conversions belonging to the fifth century are closely connected in their circumstances with the

devotion of which we are speaking. The first is that of Theophilus, œconomus or temporal administrator of the church of Adana,

in Cilicia. His history has been quoted as genuine by St. Bernard, and a vast number of ecclesiastical writers, and was originally

written by Eutychian, one of his own clergy, who declares that he relates only what he has seen with his eyes and heard with his ears.

Theophilus being deposed from his charge, apostatized from the Faith, and sold himself to the devil; then touched with remorse he

implored the aid of the Mother of God and obtained pardon and release from his terrible bondage through Her intercession, as he

prostrated before Her image,

Two celebrated conversions belonging to the fifth century are closely connected in their circumstances with the

devotion of which we are speaking. The first is that of Theophilus, œconomus or temporal administrator of the church of Adana,

in Cilicia. His history has been quoted as genuine by St. Bernard, and a vast number of ecclesiastical writers, and was originally

written by Eutychian, one of his own clergy, who declares that he relates only what he has seen with his eyes and heard with his ears.

Theophilus being deposed from his charge, apostatized from the Faith, and sold himself to the devil; then touched with remorse he

implored the aid of the Mother of God and obtained pardon and release from his terrible bondage through Her intercession, as he

prostrated before Her image, expecting from Her the hope of salvation

(image at left).

The other example is that of St. Mary of Egypt, whose death took place about the year 430. Her story has always been

held authentic, and is too well known to require more than a brief recapitulation. After leading an abandoned life for many years,

Mary finds herself at Jerusalem, on the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross (This Feast, though now observed in commemoration

of the recovery of the Holy Cross from the Persians by Heraclius in 627, was celebrated at Jerusalem from the year 335 to honor the

Dedication of the Basilicas raised by Constantine and St. Helena on Mount Calvary and over the Holy Sepulcher). But being

mysteriously withheld from entering the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, where the precious relic is exposed for veneration,

she enters into herself and conceives a horror for her past life. Suddenly she perceives above her a picture of the Holy Virgin.

Fixing my eyes upon it,

she says, I addressed myself to the Holy Virgin, begging of Her by Her incomparable purity to

succor me, defiled with such a load of sin as to render my repentance the more acceptable to God. I besought Her that I might be

suffered to enter the church to behold the sacred Wood of Redemption; promising from that moment to consecrate myself to God by a

life of penance, and to take Her for my surety in this change of heart.

After this prayer she is able to enter the church,

and having kissed the pavement with tears, and given thanks to God for His incomprehensible mercy, she returns to the picture of

the Mother of God, and falling once more on her knees before it, she prays Her to be her guide. After my prayer,

she says,

I seemed to hear this voice – If thou goest beyond the Jordan, thou shalt there find rest and comfort. Then weeping and looking

on the image I begged of the Holy Queen of the world that She would never abandon me.

And the next morning, recommending herself

to the Holy Virgin, she crosses the Jordan and begins her wonderful life of penance; in the course of which she is often attacked by

the tyranny of her former passions, but obtains deliverance by continually raising her heart to the Blessed Virgin, who never fails

to assist her by Her powerful protection.

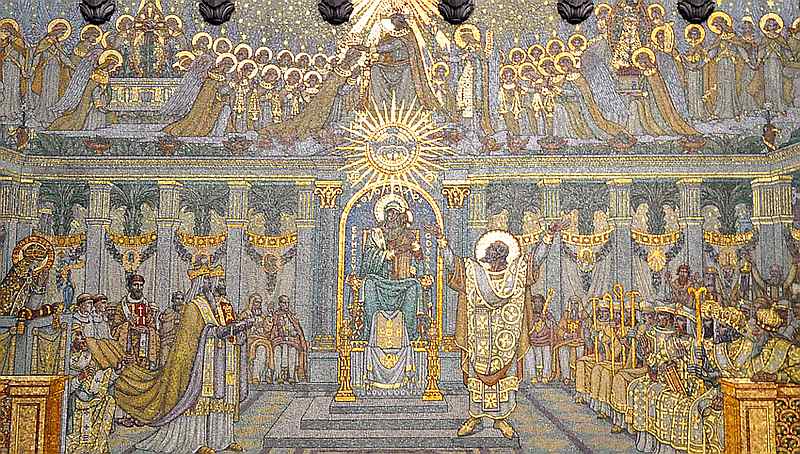

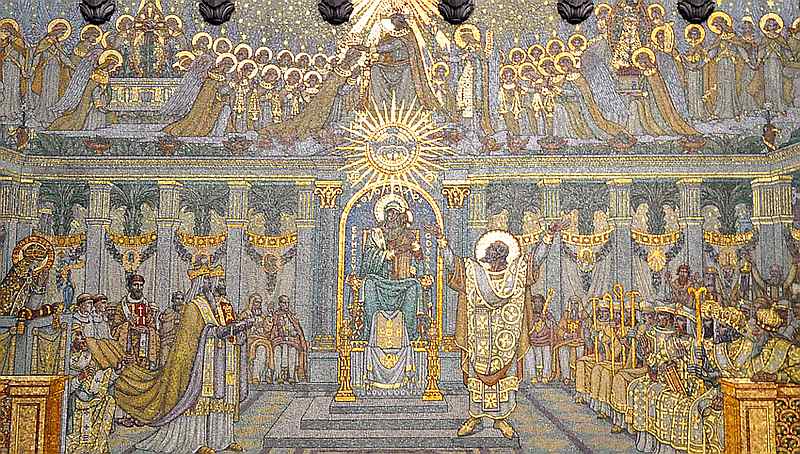

It is not to be doubted that the devotion of the faithful to the Blessed Virgin took a much fuller expansion after the

Council of Ephesus had triumphantly defended Her privileges against the attacks of Nestorius. The very fact that Her dignity as

Mother of God had been called into question by that heretic, rendered every devout Catholic eager to give testimony to his own fidelity,

and to multiply the exterior signs of his filial homage. The possible danger of encouraging idolatry which up to that time may have

imposed a certain reserve on the manifestation of their devotion no longer existed, for the struggle with idolatry had ended;

nothing therefore checked the free expression of those sentiments which had been outraged by the impiety of Nestorius.

But the difference to be observed in this devotion as it existed before and after the Council of Ephesus, was not one of

principle; and if we desire to know what was the precise feeling of the faithful on this point, at the very outset of the controversy

we find it expressed in that cry of horror with which the people of Constantinople fled from the church in which Dorotheus of

Marcianopolis utterd his blasphemous anathema against those who should give to Mary the title of Mother of God. In fact, if one may

say so, the Nestorian heresy was condemned by the populace before it was condemned by their rulers. It was notoriously a novelty,

so directly opposed to the Christian instinct and tradition, that the first rumor of it created a popular commotion. This is sufficient

to show that the devotion was not created by the Council of Ephesus; and, as Socrates the historian observes (lib. 7, c. xxxxii),

Nestorius by objecting to the title of Theotokos as applied to Mary, displayed his ignorance of the ancient fathers,

which he never seemed to have read, for they certainly were not afraid to use this title. He quotes particularly Origen, who in his

commentaries on the Epistle to the Romans, discourses at large on this matter, and alleges the cause why Mary is called the Mother of God.

That She was so called, and that not accidentally but continually, is shown by the words of Julian the Apostate, already quoted, and by

the writings of St. Dionysius of Alexandria, and of St. Athanasius, both of whom are reckoned to have used this expression eight or nine

times, and by the famous anathema of St. Gregory of Nazianzen, who, writing against the Apollinarists, says, If anyone does not

believe Mary to be the Mother of God, he is separated from the Divinity.

The Council of Ephesus.

Moreover it will be remembered that Nestorius was not the first heretic who had earned the unenviable title of the

enemy of Mary.

The previous generation had been successively assailed by the heresies of Helvidius, Jovinian and Vigilantius,

and had repudiated their impiety with a prompt indignation, little differing from that excited by the teaching of Nestorius. They were

denounced by all the great writers of the day, and in particular St. Jerome, who may be regarded as the mouthpiece of the Church

during the latter half of the fourth century. There is something very suggestive in the nature of the errors broached by this

notable band of heresiarchs. All, as we know, attacked the doctrine of Our Lady's perpetual virginity, and attempted at the same time

to overthrow the entire ascetic system of the Church. Jovinian, the Luther of his age, railed at the Catholic doctrine of merit,

made light of the counsels of perfection, and, monk as he was, opposed asceticism no less by his example than by this teaching.

He cast off his monk's habit, dressed in silk, curled his hair, and addicted himself to wine and good living. No wonder that such

a man should have been found among the enemies of Mary. Vigilantius was a man of kindred spirit; he did not like the veneration of

relics, which he called nothing better than old bones,

and those who venerated them he designated ashes-worshippers.

The custom of burning candles in the churches before these relics was a great grievance in his eyes, and he was curious to know how

God could be honored by the consumption of these miserable wax candles!

We are not at all surprised to find these sectaries

distinguishing themselves by their hostility to the Blessed Virgin, so as to earn for themselves the title of Anti-Marianites,

and their hostility is not without its value, as testifying to the fact how very marked and widely-spread the devotion to Her had become,

when they took it upon themselves to rail against it.

The lives of many other Fathers of the Church, contemporary with or anterior to St. Jerome, furnish us with the like

testimony. I am not aware that there is any incident in the life of St. Augustine directly connected with our present subject, unless

indeed we reckon as such the vision granted to St. Monica, which a recent writer has inserted in his collection of the early apparitions

of Our Lady. She is said to have appeared to her clothed in black and wearing a cincture, in memory of which was founded the Augustinian

Confraternity of the Holy Cincture of Our Lady of Consolation. But the lives of both St. Martin and St. Ambrose contain allusions to

supernatural favors received by them from Her hands.

Thus, in the beautiful life of St. Martin written by Sulpicius Severus, we read that the Blessed Virgin frequently

appeared to him in his cell, together with other Saints; and the manuscript Life of St. Ambrose preserved in the Ambrosian library

at Milan record a miraculous event which gave rise to the sanctuary of the Holy Mountain of Varese (image below). In the reign

of Valentinian II, the excesses of the Arians compelled the Catholics of those parts to take up arms in their own defense, and a combat

was fought in the neighboring plains during which St. Ambrose remained on this mountain recommending the issue of the struggle to God,

through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin. She is said to have appeared to him and to have promised him the victory, and the altar,

on which he afterwards offered the Holy Sacrifice in thanksgiving, remained on the hill as a memorial of the event. Another sanctuary

which also bears the name of the Holy Mountain is that of Oropa (image below), where is preserved a rude cedar-wood image

(at right), brought from the East by St. Eusebius of Vercelli in 361, when he returned from the exile into which he had been

driven by the Arian Emperor Constantius. Two other images were deposited by him at the same time in the churches of Crea and Cagliari,

and the Madonna della Consolata at Turin (image on home page) is likewise believed to have been presented by Saint Eusebius to

Maximus, Bishop of that city.

Thus, in the beautiful life of St. Martin written by Sulpicius Severus, we read that the Blessed Virgin frequently

appeared to him in his cell, together with other Saints; and the manuscript Life of St. Ambrose preserved in the Ambrosian library

at Milan record a miraculous event which gave rise to the sanctuary of the Holy Mountain of Varese (image below). In the reign

of Valentinian II, the excesses of the Arians compelled the Catholics of those parts to take up arms in their own defense, and a combat

was fought in the neighboring plains during which St. Ambrose remained on this mountain recommending the issue of the struggle to God,

through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin. She is said to have appeared to him and to have promised him the victory, and the altar,

on which he afterwards offered the Holy Sacrifice in thanksgiving, remained on the hill as a memorial of the event. Another sanctuary

which also bears the name of the Holy Mountain is that of Oropa (image below), where is preserved a rude cedar-wood image

(at right), brought from the East by St. Eusebius of Vercelli in 361, when he returned from the exile into which he had been

driven by the Arian Emperor Constantius. Two other images were deposited by him at the same time in the churches of Crea and Cagliari,

and the Madonna della Consolata at Turin (image on home page) is likewise believed to have been presented by Saint Eusebius to

Maximus, Bishop of that city.

Sozomen tells us that in the church or rectory at Constantinople called the Anastasia, in which St. Gregory of Nazianzen

was accustomed to gather his little flock, many miracles took place, and that the Blessed Virgin frequently appeared there.

The confidence exhibited by this great Saint in Her patronage and in that of all the Saints is expressed in many of his writings,

and it is he who relates the history of St. Justina to which we shall presently refer, and declares her deliverance to have been

wrought through the power of the Mother of God. And although we are speaking here less of the doctrine of the Fathers touching

this devotion than of facts illustrative of its practice, one cannot pass over the words of St. Epiphanius, who calls the Virgin Mother

the Mediatrix between earth and Heaven,

and denounces the heresy of the Antidicomarianites (literally the opponents of

Mary

– they denied the Perpetual Virginity of the Blessed Virgin), not only as a sacrilegious impiety,

but as a

monstrous novelty

; an important expression, as it shows that the veneration paid to Her in the fourth century, rested on the

tradition of preceding ages.

But let us take one step further back; what shall we say of St. Ephrem, the doctor of Edessa, whose hymns, but recently

brought to light (e.g. the Carmina Nisibena, published in 1866, from a manuscript in the British Museum), bear witness to his

belief in the Immaculate Conception; whose writings contain the actual words of so many of our own devotions, such as the Sub tuum

præsidium, and the well-known versicle, Dignare me laudare te, Virgo sacrata; who salutes Our Lady as his Queen,

his Sovereign, his life, his light, his hope, and his refuge, holding the second place next to the Divinity, the Mediatrix of the

whole human race; and who in his terrifying sermon on the Last Judgment paints to us the separation of the just from the wicked,

and places in the mouths of sinners that doleful cry: Farewell, ye saints and servants of God; farewell parents, farewell children;

farewell prophets, apostles, martyrs; farewell Lady, Mother of God; Thou hast prayed for us, that we might be saved, but we would

not!

And the author of these words died in 378, and was the son of parents who had confessed the Faith in the persecution of Diocletian.

Such a witness brings this devotion very close to the Age of Martyrdom; but in the person of St. Methodius of Tyre we

have one who was a martyr himself. St. Methodius does not merely write of the Blessed Virgin, but he addresses Her in the language

of invocation. And it is he who appeals in support of this devotion to the example of Our Lord Himself. We all owe debts to God,

he says, but to Thee He Himself is indebted Who has said, Honor thy father and thy mother. And that He might fulfill His own law,

and exceed all men in its observance, He paid all honor and grace to His own Mother

(S. Method. Serm. de Sim. et Anna.

In this sermon St. Methodius several times bestows on Our Lady the title of Theotokos

– the Mother of God). St. Methodius

suffered martyrdom at Chalcis, Syria during the last persecution, ca. 312.

In the reign of St. Sylvester, the very first Pope who governed the Church after the period of martyrdom, we find a

miraculous incident recorded, the cessation, namely, of a terrible pestilence, which was attributed to the intercession of the

Blessed Virgin. And in gratitude for this favor St. Sylvester (as Baronius relates) dedicated to Her honor in the Roman forum a

church known as Libera nos a pœnis (Deliver us from punishments). This must have been before the year 335, which was that of

St. Sylvester's death.

Miraculous graces granted to the invocation of Our Lady appear both in the authentic lives and the less authentic

legends belonging to the age of martyrdom. Thus the Greek acts of St. Catherine represent her as converted to the Faith by the

sight of a picture of the Holy Virgin and Her Divine Son, and as afterwards presented to Our Lord by His Blessed Mother, who entreats

Him to accept Catherine as His spouse. Then we have the legend of the two Saints, Julian and Basilissa, martyred under Maximin in 312,

who on the day of their nuptials consecrated themselves to God by a vow of chastity and devoted themselves to the service of the sick,

when Jesus and Mary visibly appeared to them, surrounded by saints and angels who say aloud, Victory to thee, Julian; victory to thee,

Basilissa!

And St. Gregory of Nazianzen relates the history of St. Justina, who was delivered from the diabolical conspiracy

framed against her by Cyprian the magician on invoking the Blessed Virgin, and whose martyrdom took place about the year 304.

(Cyprian was himself converted and died a martyr. Their Feast day is September 26.)

Earlier still, in 240, we have the celebrated vision of St. Gregory Thaumaturgus, who, as St. Gregory of Nyssa relates,

received an exposition of the Christian Faith from the dictation of the Blessed Virgin. And this incident, it may be observed,

cannot be classed among pious legends, but has always been respected as absolutely historical. This perhaps is one of the earliest

examples on record of any apparition of Our Lady, or supernatural grace received from Her hands, but it is very far from taking us

back to the earliest proof that is to be found of the devotion to Her in the Church. The catacombs, which bear witness to so many

other points of primitive faith are not silent on this matter. The Commendatore De Rossi, whose perfect candor and honesty no less

that his unrivaled ability will be admitted by critics of every creed, has published a selection of a few out of the numerous pictures

of Our Blessed Lady which we find in subterranean Rome. (Fr. Northcote co-authored Roma Sotterranea, an English version of the

Italian work of de Rossi, with his permission and assistance.) In the explanatory text with which he illustrates these paintings,

he informs us that whereas he believes some of them to belong almost, if not quite, to the Apostolic age, there are at least a score

which cannot be assigned to a later date than that of Constantine.

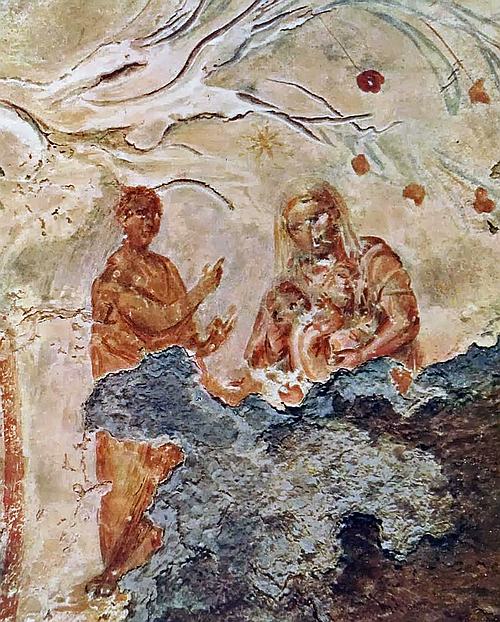

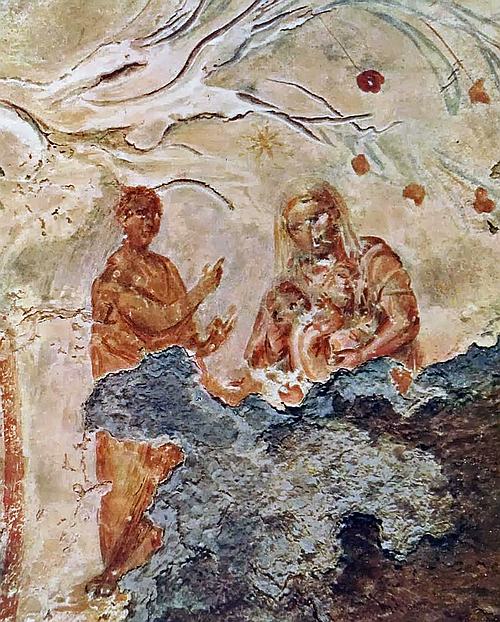

The latest of those which he published is the well-known figure of Our Blessed Lady and the Holy Child in the cemetery

of St. Agnes, which belongs probably to the middle of the fourth century; another in the cemetery of St. Domitilla, he unhesitatingly

assigns to the third century; whilst another (at left), from the cemetery of St. Priscilla, in which the prophet Isaias stands

before Her pointing to a star over Her head, he considers to belong to the very beginning of the second, if not to the first century.

The testimony of these paintings is at once most ancient and authentic. Of the examples alleged before, some we freely admit are but

legendary tales, nor are they brought forward as claiming the authority of graver history. Their value lies in this – that they show

the legendary records of the Church to have borne witness equally in every age, to the existence of this devotion to Mary. Study those

records when we will, they tell us the same tale, nor will its earlier chapters be less supernatural, or, as it may be termed,

less marvelous, than those of later date. Legends moreover are not necessarily false because they claim less critical evidence

than history; and even where they exhibit a certain coloring of romance and fiction, they may nevertheless embody a fact, or convey

accurate information as to the belief and devotion of the age to which they belong. Still more must they carry weight when we find

them strictly harmonizing with the teaching of authentic narratives. The prejudice which leads some to imagine that visions and

apparitions of Our Lady, and tales of Her direct interference in human affairs, are but the mythical produce of middle age credulity,

is startled, to say the least, when it encounters precisely similar stories told and believed by Saints belonging to the first five

centuries of the Church. This harmony of belief is a grave and indisputable fact, for it proves that the devotion of the faithful,

like their creed, is in all its main features the same now as it was in the beginning, and as it shall be in ages to come.

The latest of those which he published is the well-known figure of Our Blessed Lady and the Holy Child in the cemetery

of St. Agnes, which belongs probably to the middle of the fourth century; another in the cemetery of St. Domitilla, he unhesitatingly

assigns to the third century; whilst another (at left), from the cemetery of St. Priscilla, in which the prophet Isaias stands

before Her pointing to a star over Her head, he considers to belong to the very beginning of the second, if not to the first century.

The testimony of these paintings is at once most ancient and authentic. Of the examples alleged before, some we freely admit are but

legendary tales, nor are they brought forward as claiming the authority of graver history. Their value lies in this – that they show

the legendary records of the Church to have borne witness equally in every age, to the existence of this devotion to Mary. Study those

records when we will, they tell us the same tale, nor will its earlier chapters be less supernatural, or, as it may be termed,

less marvelous, than those of later date. Legends moreover are not necessarily false because they claim less critical evidence

than history; and even where they exhibit a certain coloring of romance and fiction, they may nevertheless embody a fact, or convey

accurate information as to the belief and devotion of the age to which they belong. Still more must they carry weight when we find

them strictly harmonizing with the teaching of authentic narratives. The prejudice which leads some to imagine that visions and

apparitions of Our Lady, and tales of Her direct interference in human affairs, are but the mythical produce of middle age credulity,

is startled, to say the least, when it encounters precisely similar stories told and believed by Saints belonging to the first five

centuries of the Church. This harmony of belief is a grave and indisputable fact, for it proves that the devotion of the faithful,

like their creed, is in all its main features the same now as it was in the beginning, and as it shall be in ages to come.

And now what conclusion shall we draw from such facts and narratives as have been here collected? They present us with

a devotion which appears in all times to have manifested itself by means of certain exterior acts of worship of a particular character,

such as the veneration of certain pictures and images in preference to others and the frequentation of favorite sanctuaries, under the

belief that such spots were more highly favored than others, and that prayers offered there have some special likelihood to be heard.

Such a belief, though by some it may be qualified as superstitious, is not, it must be owned, without its Scriptural warrant; for God

Himself by the mouth of Moses promised that He would choose a place for His people, that His Name might be therein

(Deut. 12: 11). And the prayer of Solomon at the dedication of the temple was that the Lord would hearken to the supplications

of His people Israel and grant whatsoever they should pray for in this place

(3 Kings 8: 30). And there was but one

part of Bethsaida that we know of in Jerusalem into which an angel of the Lord descended at certain times, and the water was moved.

And he that went down first into the pool after the motion of the water was made whole of whatsoever infirmity he lay under

(John 5: 4).

If then we admit that some places may be more favored than others in this respect, and that the disposition to regard

with reverence any spot once marked as the scene of special grace is both reasonable in itself and supported by many Scriptural examples,

the practice of pilgrimages will flow from such a feeling as its inevitable consequence. In the foregoing paragraphs and chapters,

it has been shown that this practice has not been confined to any particular age, or country, or class of men, but that it is rather

one of those indigenous flowers of the Faith, which is native to the soil and springs from it spontaneously without care of culture.

It is a part of that natural language by which men give expression to their religious sense, when the heart charged with emotions of

gratitude or veneration seeks relief in some exterior act. If all do not feel the need of such exterior expression in an equal degree,

the mass of men, and especially the simpler orders, will always be sensible of this instinct of the heart, which prompts them to give

outward manifestations of their interior worship. There is a necessity on them which will not suffer them to rest without doing

something to pour forth their love; a homely feeling, far removed from the transcendental, yet one which seems to have something

in it akin to the words of Psalmist, What shall I render unto the Lord for all that He hath rendered unto me?

(Ps. 115)

Sanctuary of Varese.

Worship of this sort will for the most part express itself in acts entailing sacrifice. The scoffer may smile at the

spectacle which presents itself in not a few foreign churches where a somewhat unsightly candelabra stands before some favorite image

for the convenience of any devout soul who wishes to burn a candle. They may question the use of the ornamental character of some of

the offerings to be seen suspended before a popular Madonna; and in precisely the same spirit they may criticize the reasonableness of

pilgrimages. But these and many other popular expressions of Catholic piety are intelligible enough as outpourings of that instinct

of which we have spoken, which desires to give to God of that which has cost us something; the offering may be homely, but the spirit

which dictates it is truly royal, and to him who so offers may be spoken the words of Areuna the Jebusite: The Lord thy God receive

thy vow.

It may no doubt be urged that the particular form of popular devotion of which we have here been speaking is liable to

grave abuses; that for one who undertakes a pilgrimage from a motive of piety, ten are guided by curiosity; that even in what we call

the ages of Faith, St. Boniface had to complain not merely of the disorders committed by the English pilgrims of his time, but of

positive scandals, and that the words of Thomas a Kempis have passed into a proverb, They who often go on pilgrimage, are rarely

sanctified.

Even St. John of the Cross, when speaking of pilgrimages in his own beautiful style, points out the abuses to which

they are liable and advises that they should not be made at seasons when the holy places are the resort of a crowd. God,

he says (speaking of the devotion to holy images), for the greater purification of this devotion, when He grants graces and works

miracles, does so generally through images not very artistically adorned, so that the faithful may attribute nothing to the skill

of the artist. And very often Our Lord grants His graces by means of images in remote and solitary places. In remote places,

that the pilgrimage to them may stir up our devotion and make it more intense. And in solitary places, that we may retire from

the noise and concourse of men to pray in solitude like Our Lord Himself. He who goes on a pilgrimage will do well to do so when

others do not, even at an unusual time. When many persons make a pilgrimage I would advise staying at home, for in general men

return from such expeditions more dissipated than they were before. And many become pilgrims for recreation rather than devotion

(Ascent of Mount Carmel c. xxxv).

But the abuse of a thing may be freely admitted without prejudice to its sanctity. We might as well argue against the

frequentation of churches as a means of sanctification, because out of the crowds that fill our places of worship, many may be found

there who display irreverence or vanity. And because the pious author first quoted (Kempis) also observes – no doubt with equal

justice – few are made better by sickness,

we are not therefore disposed to doubt that sickness has been the instrument of

sanctification to innumerable souls.

Acknowledging however the general truth conveyed in the proverb, and admitting that the merely external performance of

popular devotions will sanctify no one, and that there exists in many souls a certain restlessness and love of excitement which requires

to be starved rather than to be gratified, we cannot nevertheless refuse to number pilgrimages, devoutly performed, among the means of

holiness

which the church offers to Her children. Perhaps there is no spiritual exercise better fitted than this to kindle within

us the flame of piety. A journey, especially on foot, undertaken from a religious motive, through localities but scantily furnished

with comforts and conveniences, has in itself a certain element of penance, and powerfully brings to the heart the thought of Him Who

was once a wayfarer on the hills of Galilee and Judea, and Who had not where to lay His head. To men of pensive mood the act in which

they are engaged is a prolonged meditation; it reminds them that they are pilgrims and strangers,

sojourners on the earth as

all their fathers were;

it does violence to some of those conventional usages and maxims to which Englishmen are so much enslaved;

to the social idolatry of home comforts, which we renounce for a time, neither for the sake of profit nor pleasure, but only that we

may renew the freshness of our spiritual life at some sweet fountain-head of piety; and it induces a most happy forgetfulness of our

own self-importance when we find ourselves one in a vast crowd gathered out of many lands, between whom and ourselves there exists no

tie save that of the Catholic Faith.

There is another reflection which suggests itself in a very consoling way to those who follow on the pilgrims track.

How universal is the Providence of God! We know indeed His care and His love are for all His children, but in how vivid and sensible

a manner do we realize this as we wander through the obscure valleys and villages of France, of Belgium, of Poland, of Catholic America,

and everywhere meet with the footprints of His grace. And this thought links itself to one which is more specially connected with the

sanctuaries of the Madonna. We have before now heard the number and variety of these sanctuaries spoken of as tending to confuse the

minds of the ignorant, and even to give them the impression that there may be more objects than one of their filial devotion,

and that the Madonna of Loreto is a distinct personage from the Madonna of Montserrat. But we must confess that the extraordinary

multiplication of Our Lady's sanctuaries, has always appeared to us one of the most remarkable features in the history of popular

devotion. Other Saints are venerated more or less in particular localities; they are invoked as Patrons of this city or that province;

but the Patronage of Our Lady is universal. And nevertheless the maternal character of Her protection is shown precisely in this,

that at the same time that it is universal, it is particular also. There is not a Religious Order but has its own peculiar legend,

whereby it claims Our Lady as its own special Patroness. There is not a Christian nation but would have us believe that Our Lady

regards them as Her special clients. If the golden fleurs-de-lys were borne in honor of Notre Dame de France, England in old time

boasted of being the dowry of Mary.

If the Carmelites glory in calling themselves the brothers and sisters of the Blessed Virgin,

the Cistercians find equal satisfaction in wearing their white habit in Her honor, and the Dominicans and Franciscans alike console

themselves with the heavenly visions which show their departed members gathered under the shelter of Her mantle.

Sanctuary of Oropa.

It is the same with Her sanctuaries, which cluster so thickly in every country where the Faith is lingering still.

There is no province, we had almost said no village, of Christendom but has its own Madonna; and linked with that holy image some legend,

or succession of legends, which marks that spot as a chosen resting-place selected for the outpouring of Her maternal favors.

Thus every child in the vast family regards Her as his own Mother; She is bound to each one by some individual tie; and as we take our

way from Boulogne to Fourvière, from Fourvière to Laus, through the Catholic cantons of Switzerland, or among the hundreds of sanctuaries

which the Spanish peninsula alone still boasts of possessing, we feel that Mary is indeed the Mother of us all,

that the devotion

rendered to Her is no vague offspring of the imagination, but something which attests Her active, personal, and universal care;

so that by Her devout clients, Her protection is felt almost as a presence, not visible indeed to our outward sense, but easily

discernible by the affections. Such was the devotion rendered by our Catholic forefathers to Her; and in their language,

so sweetly blending familiarity with reverence, we will close these pages:

Lady, Seint Mary, fayre and gode and swete,

For love of Ye teres Thi self lete,

Gyve me grace on erthe my sines to hete,

And that I may in Heven sitten at Thi fete.

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

The examples which have been cited in the foregoing articles chiefly exhibit the devotion to Our Lady in either its

modern or its medieval aspect. But it would not be difficult to trace back the same devotion into far earlier ages, and present

the reader with illustrations gathered from the sixth, the fourth, or the second centuries, differing but little in their general

character from those with which we have hitherto been engaged. Not merely do the writings of the Fathers lay down those dogmas of

Faith which form the root and groundwork of our devotion to the Blessed Virgin, but history and tradition reveal to us the devotion

itself as practiced even in the desert and in the catacombs. However far we travel back we are met by facts and legends attesting

the universal belief in the power of Our Lady's intercession, and this power is represented as often miraculously displayed.

The annals of the Eastern Empire are as rich in such narratives as those of Western Christendom; and a few examples may be selected

from the first six centuries as best showing the identity of the ancient with the modern devotion.

The examples which have been cited in the foregoing articles chiefly exhibit the devotion to Our Lady in either its

modern or its medieval aspect. But it would not be difficult to trace back the same devotion into far earlier ages, and present

the reader with illustrations gathered from the sixth, the fourth, or the second centuries, differing but little in their general

character from those with which we have hitherto been engaged. Not merely do the writings of the Fathers lay down those dogmas of

Faith which form the root and groundwork of our devotion to the Blessed Virgin, but history and tradition reveal to us the devotion

itself as practiced even in the desert and in the catacombs. However far we travel back we are met by facts and legends attesting

the universal belief in the power of Our Lady's intercession, and this power is represented as often miraculously displayed.

The annals of the Eastern Empire are as rich in such narratives as those of Western Christendom; and a few examples may be selected

from the first six centuries as best showing the identity of the ancient with the modern devotion. Of Leo I, one of the worthiest of the Christian Emperors, a story is repeated by Nicephorus, to the effect that his future elevation

to the empire was made known to him when still a simple soldier, by Our Lady Herself, who appeared to him as he was charitably assisting

a poor blind man. The devotion of his predecessors, Marcian and St. Pulcheria, is spoken of by all historians. It was they who erected

the three great churches in Constantinople – the Chalcopratum, in which was preserved the girdle of Our Lady; in the Blaquerna, some

bands that had been wrapt around Her sacred body at Her entombment, and a picture, often borne before the emperors in processsions of

triumph; and in the Hodegus, another yet more celebrated picture, which was said to have been painted by Saint Luke, (above and

at left) and which had been sent to St. Pulcheria from Jerusalem by the Empress Eudoxia. It received the title of the Hodegetria,

and the custom became established for the Greek emperor to come here before setting out on any military expedition, in order to take

leave of Our Lady and ask Her blessing.

Of Leo I, one of the worthiest of the Christian Emperors, a story is repeated by Nicephorus, to the effect that his future elevation

to the empire was made known to him when still a simple soldier, by Our Lady Herself, who appeared to him as he was charitably assisting

a poor blind man. The devotion of his predecessors, Marcian and St. Pulcheria, is spoken of by all historians. It was they who erected

the three great churches in Constantinople – the Chalcopratum, in which was preserved the girdle of Our Lady; in the Blaquerna, some

bands that had been wrapt around Her sacred body at Her entombment, and a picture, often borne before the emperors in processsions of

triumph; and in the Hodegus, another yet more celebrated picture, which was said to have been painted by Saint Luke, (above and

at left) and which had been sent to St. Pulcheria from Jerusalem by the Empress Eudoxia. It received the title of the Hodegetria,

and the custom became established for the Greek emperor to come here before setting out on any military expedition, in order to take

leave of Our Lady and ask Her blessing.

Two celebrated conversions belonging to the fifth century are closely connected in their circumstances with the

devotion of which we are speaking. The first is that of Theophilus, œconomus or temporal administrator of the church of Adana,

in Cilicia. His history has been quoted as genuine by St. Bernard, and a vast number of ecclesiastical writers, and was originally

written by Eutychian, one of his own clergy, who declares that he relates only what he has seen with his eyes and heard with his ears.

Theophilus being deposed from his charge, apostatized from the Faith, and sold himself to the devil; then touched with remorse he

implored the aid of the Mother of God and obtained pardon and release from his terrible bondage through Her intercession, as he

prostrated before Her image,

Two celebrated conversions belonging to the fifth century are closely connected in their circumstances with the

devotion of which we are speaking. The first is that of Theophilus, œconomus or temporal administrator of the church of Adana,

in Cilicia. His history has been quoted as genuine by St. Bernard, and a vast number of ecclesiastical writers, and was originally

written by Eutychian, one of his own clergy, who declares that he relates only what he has seen with his eyes and heard with his ears.

Theophilus being deposed from his charge, apostatized from the Faith, and sold himself to the devil; then touched with remorse he

implored the aid of the Mother of God and obtained pardon and release from his terrible bondage through Her intercession, as he

prostrated before Her image,

Thus, in the beautiful life of St. Martin written by Sulpicius Severus, we read that the Blessed Virgin frequently

appeared to him in his cell, together with other Saints; and the manuscript Life of St. Ambrose preserved in the Ambrosian library

at Milan record a miraculous event which gave rise to the sanctuary of the Holy Mountain of Varese (image below). In the reign

of Valentinian II, the excesses of the Arians compelled the Catholics of those parts to take up arms in their own defense, and a combat

was fought in the neighboring plains during which St. Ambrose remained on this mountain recommending the issue of the struggle to God,

through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin. She is said to have appeared to him and to have promised him the victory, and the altar,

on which he afterwards offered the Holy Sacrifice in thanksgiving, remained on the hill as a memorial of the event. Another sanctuary

which also bears the name of the Holy Mountain is that of Oropa (image below), where is preserved a rude cedar-wood image

(at right), brought from the East by St. Eusebius of Vercelli in 361, when he returned from the exile into which he had been

driven by the Arian Emperor Constantius. Two other images were deposited by him at the same time in the churches of Crea and Cagliari,

and the Madonna della Consolata at Turin (image on home page) is likewise believed to have been presented by Saint Eusebius to

Maximus, Bishop of that city.

Thus, in the beautiful life of St. Martin written by Sulpicius Severus, we read that the Blessed Virgin frequently

appeared to him in his cell, together with other Saints; and the manuscript Life of St. Ambrose preserved in the Ambrosian library

at Milan record a miraculous event which gave rise to the sanctuary of the Holy Mountain of Varese (image below). In the reign

of Valentinian II, the excesses of the Arians compelled the Catholics of those parts to take up arms in their own defense, and a combat

was fought in the neighboring plains during which St. Ambrose remained on this mountain recommending the issue of the struggle to God,

through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin. She is said to have appeared to him and to have promised him the victory, and the altar,

on which he afterwards offered the Holy Sacrifice in thanksgiving, remained on the hill as a memorial of the event. Another sanctuary

which also bears the name of the Holy Mountain is that of Oropa (image below), where is preserved a rude cedar-wood image

(at right), brought from the East by St. Eusebius of Vercelli in 361, when he returned from the exile into which he had been

driven by the Arian Emperor Constantius. Two other images were deposited by him at the same time in the churches of Crea and Cagliari,

and the Madonna della Consolata at Turin (image on home page) is likewise believed to have been presented by Saint Eusebius to

Maximus, Bishop of that city. The latest of those which he published is the well-known figure of Our Blessed Lady and the Holy Child in the cemetery

of St. Agnes, which belongs probably to the middle of the fourth century; another in the cemetery of St. Domitilla, he unhesitatingly

assigns to the third century; whilst another (at left), from the cemetery of St. Priscilla, in which the prophet Isaias stands

before Her pointing to a star over Her head, he considers to belong to the very beginning of the second, if not to the first century.

The testimony of these paintings is at once most ancient and authentic. Of the examples alleged before, some we freely admit are but

legendary tales, nor are they brought forward as claiming the authority of graver history. Their value lies in this – that they show

the legendary records of the Church to have borne witness equally in every age, to the existence of this devotion to Mary. Study those

records when we will, they tell us the same tale, nor will its earlier chapters be less supernatural, or, as it may be termed,

less marvelous, than those of later date. Legends moreover are not necessarily false because they claim less critical evidence

than history; and even where they exhibit a certain coloring of romance and fiction, they may nevertheless embody a fact, or convey

accurate information as to the belief and devotion of the age to which they belong. Still more must they carry weight when we find

them strictly harmonizing with the teaching of authentic narratives. The prejudice which leads some to imagine that visions and

apparitions of Our Lady, and tales of Her direct interference in human affairs, are but the mythical produce of middle age credulity,

is startled, to say the least, when it encounters precisely similar stories told and believed by Saints belonging to the first five

centuries of the Church. This harmony of belief is a grave and indisputable fact, for it proves that the devotion of the faithful,

like their creed, is in all its main features the same now as it was in the beginning, and as it shall be in ages to come.

The latest of those which he published is the well-known figure of Our Blessed Lady and the Holy Child in the cemetery

of St. Agnes, which belongs probably to the middle of the fourth century; another in the cemetery of St. Domitilla, he unhesitatingly

assigns to the third century; whilst another (at left), from the cemetery of St. Priscilla, in which the prophet Isaias stands

before Her pointing to a star over Her head, he considers to belong to the very beginning of the second, if not to the first century.

The testimony of these paintings is at once most ancient and authentic. Of the examples alleged before, some we freely admit are but

legendary tales, nor are they brought forward as claiming the authority of graver history. Their value lies in this – that they show

the legendary records of the Church to have borne witness equally in every age, to the existence of this devotion to Mary. Study those

records when we will, they tell us the same tale, nor will its earlier chapters be less supernatural, or, as it may be termed,

less marvelous, than those of later date. Legends moreover are not necessarily false because they claim less critical evidence

than history; and even where they exhibit a certain coloring of romance and fiction, they may nevertheless embody a fact, or convey

accurate information as to the belief and devotion of the age to which they belong. Still more must they carry weight when we find

them strictly harmonizing with the teaching of authentic narratives. The prejudice which leads some to imagine that visions and

apparitions of Our Lady, and tales of Her direct interference in human affairs, are but the mythical produce of middle age credulity,

is startled, to say the least, when it encounters precisely similar stories told and believed by Saints belonging to the first five

centuries of the Church. This harmony of belief is a grave and indisputable fact, for it proves that the devotion of the faithful,

like their creed, is in all its main features the same now as it was in the beginning, and as it shall be in ages to come.