Maria hat geholfen – Mary has helped.

These three words, so often repeated in the

Gnadenkapelle (Chapel of Grace), on its countless votive tablets, rightly determine the image of Our Lady

of Altötting as the heart of Catholic Bavaria. Moreover, the Black Madonna of Altötting and the continual pilgrimages

there are among the most well-known of central Europe. What is less known is the history of this shrine.

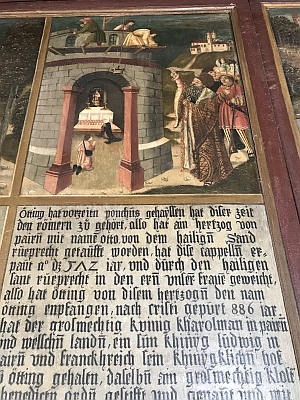

One of the votive tablets, dating from the 16th century, attempts to depict the

shrine's earliest years:

One of the votive tablets, dating from the 16th century, attempts to depict the

shrine's earliest years:

Long ago Ötting was called Ponchus, and in that time belonged to the Romans, with a Duke of standing called Otto, who was baptized by the holy St. Rupert, and who built this chapel in 572 AD, consecrated by the holy St. Rupert in honor of our Dear Lady. Thus did Ötting take its name from this Duke.

As to the source of the name of Ötting, it really matters little in the history of this Shrine. It should be pointed out that Ötting was divided into the old and new sections in the 13th century – and so we have now the cities of Altötting and Neuötting.

There is historical record of a Bavarian Duke named Uto (also called Utilo), who may have been

the source of the name of Ötting. But he reigned from 540 to 550 – well before the year given on the votive tablet.

The facts do show clearly, however, that St. Rupert was called to this land by a Bavarian Duke named Theodo, to revive

true Christianity. Irish missionaries from the times of St. Columban had already achieved some success in Bavaria,

a fact proven by archaeological findings, such as graves dating back to the 6th century. The oldest churches date back

to the first half of the 7th century – such as the Martinskirche in Salzburg and the Georgskirche in Regensburg.

But the area fell prey to Arianism and superstition – thus the need for St. Rupert's apostolate. The question is,

when exactly did St. Rupert live? The date of 572 indicated by the votive tablet is close to that which was formerly

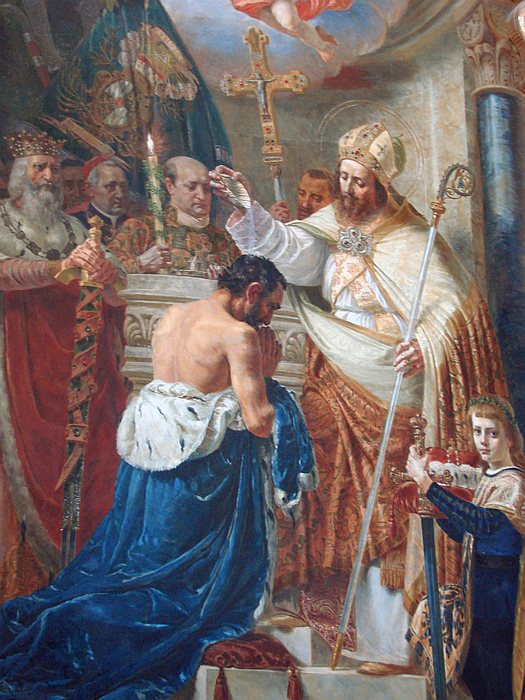

the consensus opinion – that St. Rupert was called to Bavaria in 580 by Duke Theodo III, who with his whole household

received Baptism from the Saint. However Fr. Alban Butler tells us that

There is historical record of a Bavarian Duke named Uto (also called Utilo), who may have been

the source of the name of Ötting. But he reigned from 540 to 550 – well before the year given on the votive tablet.

The facts do show clearly, however, that St. Rupert was called to this land by a Bavarian Duke named Theodo, to revive

true Christianity. Irish missionaries from the times of St. Columban had already achieved some success in Bavaria,

a fact proven by archaeological findings, such as graves dating back to the 6th century. The oldest churches date back

to the first half of the 7th century – such as the Martinskirche in Salzburg and the Georgskirche in Regensburg.

But the area fell prey to Arianism and superstition – thus the need for St. Rupert's apostolate. The question is,

when exactly did St. Rupert live? The date of 572 indicated by the votive tablet is close to that which was formerly

the consensus opinion – that St. Rupert was called to Bavaria in 580 by Duke Theodo III, who with his whole household

received Baptism from the Saint. However Fr. Alban Butler tells us that Mabillon and Bulteau, upon no slight grounds,

believe this Saint (Rupert) to have lived a whole century later than is commonly supposed, and that he founded the

church of Salzburg about the year 700.

Fr. Butler favored this opinion, and so the Duke Theodo he mentions

would have been Theodo VI.

Again, this matters little to the history of the Shrine. Modern historians, who love to doubt everything, make no exception in their skepticism about the traditions surrounding the Shrine of Altötting. However, more traditional historians have consistently pointed out that there is no clear reason or evidence for doubting these traditions.

Thus it is believed that while the original octagonal structure of the Gnadenkapelle was perhaps built by Duke Uto at an earlier date, it was converted to a Christian chapel – perhaps even a baptistery (suggested by its octagonal shape) – by the Duke Theodo baptized by St. Rupert. It is also believed that the original image of Our Lady of Altötting (Gnadenbild) was provided by St. Rupert or Duke Theodo, and that the present-day image, carved from linden wood, is the original.

The votive tablet goes on to say that King Carloman, the great-grandson of St. Karl the Great (Charlemagne), made Ötting the center of his kingdom, and built a Benedictine monastery and a basilica there. Carloman died and was buried in Ötting in 880, although his tomb has never been found. Ötting began to lose its importance in the tenth century, after several invasions by the Hungarians. St. Heinrich II restored some of the royal and religious buildings there, but it was not until the fifteenth century that Altötting became famous as a place of pilgrimage. This was due to two great miracles which took place in the year 1489.

A three year old boy fell into a stream in Altötting, and was pulled out dead a half hour later.

His mother, professing a great trust in the Blessed Virgin Mary, carried her dead child to the Gnadenkapelle.

She laid him on the altar, fell to her knees and begged for her child's life to be restored. Immediately the

child came back to life. Some time later, a farmer of Altötting led a cart loaded with oats to his house and

sat his six year old son on the horse. The child fell from the horse under the cart, and was so badly crushed

that there seemed no hope for his life. The family made a vow and called upon Our Lady of Altötting. The next

day the boy was fully recovered.

A three year old boy fell into a stream in Altötting, and was pulled out dead a half hour later.

His mother, professing a great trust in the Blessed Virgin Mary, carried her dead child to the Gnadenkapelle.

She laid him on the altar, fell to her knees and begged for her child's life to be restored. Immediately the

child came back to life. Some time later, a farmer of Altötting led a cart loaded with oats to his house and

sat his six year old son on the horse. The child fell from the horse under the cart, and was so badly crushed

that there seemed no hope for his life. The family made a vow and called upon Our Lady of Altötting. The next

day the boy was fully recovered.

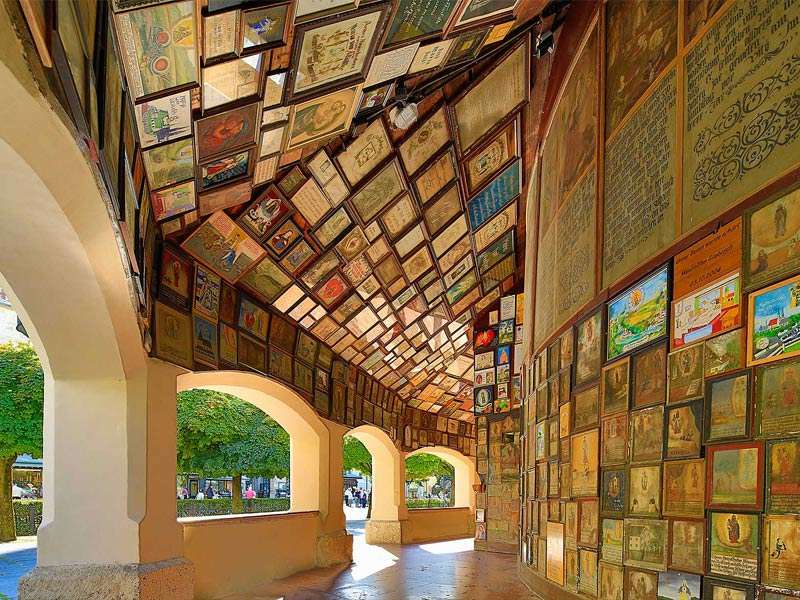

News of the intercessory power of Our Lady of Altötting spread like wildfire. Soon there were hundreds

and thousands of pilgrims visiting the shrine. Within a few years, a rectangular nave had to be built on to the original

octagonal chapel, and the entire structure was surrounded by a covered gallery. Soon the walls of the nave and gallery,

and even the ceiling of the latter became filled with ex-voto tablets and paintings. It is estimated that over 50,000

votive tablets have been donated over the centuries, but only about 2,000 remain for public view. The gallery is also

equipped with wooden crosses of various sizes, so that the pilgrims may carry them on their shoulders as they circle the

chapel while reciting their rosaries and devotions – sometimes advancing on their knees.

News of the intercessory power of Our Lady of Altötting spread like wildfire. Soon there were hundreds

and thousands of pilgrims visiting the shrine. Within a few years, a rectangular nave had to be built on to the original

octagonal chapel, and the entire structure was surrounded by a covered gallery. Soon the walls of the nave and gallery,

and even the ceiling of the latter became filled with ex-voto tablets and paintings. It is estimated that over 50,000

votive tablets have been donated over the centuries, but only about 2,000 remain for public view. The gallery is also

equipped with wooden crosses of various sizes, so that the pilgrims may carry them on their shoulders as they circle the

chapel while reciting their rosaries and devotions – sometimes advancing on their knees.

With the burning of so many votive candles, not only the Image of Our Lady, but even the walls of the chapel

were blackened. Sometime around the year 1630 a unique remedy was applied – the walls were painted black. This provides

a wonderful background for the votive tablets, and even more so for the immense amount of silver and gold decorating the

chapel. Two red marble altars in the nave flank the portal leading to the original octagonal chapel – the inner chapel

of Grace. The altar on the left is dedicated to Our Mother of Sorrows; that on the right to St. Anne. Above the portal,

along with other votive offerings, are the most beautiful of the large votive candles donated by pilgrims.

Entering the inner chapel, one experiences the feeling of being

Entering the inner chapel, one experiences the feeling of being under Mary's mantle.

The linden wood

image of Our Lady holding the Christ Child is always covered with magnificent robes, which are changed for the

various seasons, and adorned with jewels. In front of the niche, which is entirely decorated in silver, stands the

Gnadenaltar (Altar of Grace), a composition of 17th century artwork. The silver tabernacle for the miraculous

image of the Virgin Mary, donated in 1645 by elector Maximilian I, conceals a letter in its pedestal. In this document,

written in his own blood, Maximilian consecrates himself to the Madonna of Altötting. The side walls of the niche

have been decked out with a gold and silver representation of the Jesse Tree since 1670. Three years later the

altar received a silver relief image of the Holy Trinity around the top of its arch. Gold bands reach toward Our Lady

from each of the Three Divine Persons, with the wording (in Latin): Daughter of God the Father; Mother of God

the Son; Bride of the Holy Ghost.

Beneath the Gnadenbild is the silver Blessed Sacrament Tabernacle,

which was added in 1793.

Two kneeling silver figures are on the sides of the altar. That on the right, donated by the future Emperor

Karl VII and his wife Amalia, was to express their gratitude for the recovery of their seriously ill son. The parents had

vowed to donate a figure in silver weighing the same as the ailing child, should he be cured. Since 1931 the

silver prince

has been joined by the silver figure of St. Konrad of Parzham. Bruder Konrad,

a Capuchin lay

brother, had carried out the duties as a Mass server at the Gnadenaltar daily, as well as being porter of his monastery.

The holy religious was beatified in 1930 – just one year before the installation of the statue.

The heart-shaped urns – which also serve as candle stands – fixed to the wall around the Gnadenaltar, represent the ardent devotion of the Bavarian royal House of Wittelsbach towards the Madonna of Altötting. Fifteen members of the royal family willed that their hearts should be placed in these urns after death, so as to be always close to Our Lady. Even more silver ex voto offerings are encased in the niches on either side of the Altar.

Like so many other major shrines in Europe, here in Altötting a number of churches and chapels have sprung up

surrounding the central Gnadenkapelle. Across the square to the south is the Parish Church of Ss. Philip and James.

This beautiful late gothic structure, built between 1499-1511, was constructed on the remains of at least three other

buildings – the 9th century basilica of King Carloman, another structure from about the year 1000, and the 13th century

collegiate church of Duke Ludwig I. (A

Like so many other major shrines in Europe, here in Altötting a number of churches and chapels have sprung up

surrounding the central Gnadenkapelle. Across the square to the south is the Parish Church of Ss. Philip and James.

This beautiful late gothic structure, built between 1499-1511, was constructed on the remains of at least three other

buildings – the 9th century basilica of King Carloman, another structure from about the year 1000, and the 13th century

collegiate church of Duke Ludwig I. (A collegiate church

is a church of some importance, other than a cathedral,

which is staffed by a permanent college

of canons – clerics who are not monks – whose main occupation is the

celebration of the Divine Office and the Sacred Liturgy.) On the south side of this church is the collegiate cloister

with its own chapels. The most famous of these is the so-called Tilly Chapel, named after Field Marshal Johann

Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, who is buried in the crypt. From 1620-31 he successfully led the Catholic forces in the

Thirty Years War against the Protestants. His piety caused him to be nicknamed the monk in armor.

On the east end of the chapel square is the Magdalenakirche (Church of St. Mary Magdalene). With its elegant but simple interior decorated with Italian stucco, this structure was built in 1697 to replace an older church given to the care of the Jesuits. Later it was staffed by the Knights of Malta, who added a distinctive Maltese cross above the main altar. Later it was given to the care of the Redemptorists, and finally to the Capuchins. It has been traditionally the principal place for pilgrims to avail themselves of the Sacrament of Penance.

A somewhat longer distance away to the west of the chapel square is the Capuchin Monastery. Built between

1653-57, it was originally named after St. Anne, Mother of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Some years after the canonization of

Bruder Konrad by Pope Pius XI on May 20, 1934, it was renamed after him. The principle relics of St. Konrad are enshrined

in the monastery church, also named after him, but which, unfortunately, was renovated in a modernistic style.

Still there may be seen therein some beautiful stained glass windows depicting the life of the holy lay brother.

And of course, all the places which he sanctified by his holy life can be visited by pilgrims, including the tiny cell

under the stairway, which had a view of the tabernacle in the monastery chapel. St. Konrad named this cell after St. Alexius.

A somewhat longer distance away to the west of the chapel square is the Capuchin Monastery. Built between

1653-57, it was originally named after St. Anne, Mother of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Some years after the canonization of

Bruder Konrad by Pope Pius XI on May 20, 1934, it was renamed after him. The principle relics of St. Konrad are enshrined

in the monastery church, also named after him, but which, unfortunately, was renovated in a modernistic style.

Still there may be seen therein some beautiful stained glass windows depicting the life of the holy lay brother.

And of course, all the places which he sanctified by his holy life can be visited by pilgrims, including the tiny cell

under the stairway, which had a view of the tabernacle in the monastery chapel. St. Konrad named this cell after St. Alexius.

St. Anne was not forgotten by the Capuchins, however. A neo-baroque basilica in her honor was built between 1910-12 as an effort to have a church sufficiently large for the growing number of pilgrims – it can hold over 8,000 worshipers. One year after its consecration, it was named a Papal Basilica by St. Pope Pius X. Indeed, this saintly Pontiff is depicted above the main altar along with St. Anne and the Holy Child Mary. Its many beautiful side altars, and a Chapel of Our Sorrowful Mother on its eastern extremity, make this magnificent church the crowning jewel of the Sanctuary of Altötting.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com