Adapted from Various Sources.

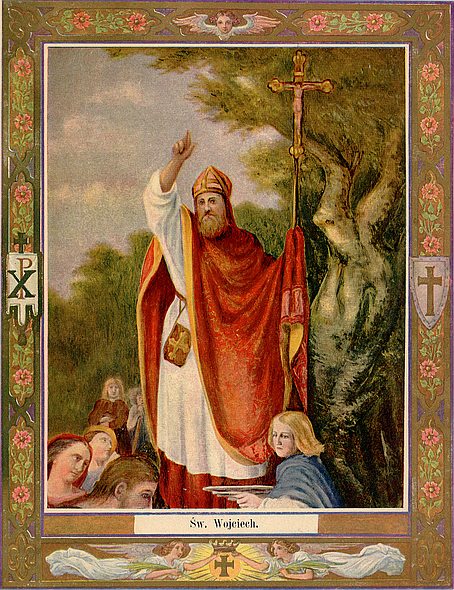

St. Adalbert, Bishop of Prague and Martyr, First Apostle of Prussia († 997; Feast – April 23)

He was born of noble parentage in Bohemia, in 956, and received at Baptism the name of Wojciech, which in the Slavic tongue signifies

Help of the Army. In his childhood his parents saw themselves in great danger of losing him by sickness, and in that extremity,

consecrated him to God by vow, before the altar of the Blessed Virgin, saying:

He was born of noble parentage in Bohemia, in 956, and received at Baptism the name of Wojciech, which in the Slavic tongue signifies

Help of the Army. In his childhood his parents saw themselves in great danger of losing him by sickness, and in that extremity,

consecrated him to God by vow, before the altar of the Blessed Virgin, saying: O Lord, let not this son live to us, but to Thee,

among the clergy, and under the patronage of Thy Holy Mother.

The child, hereupon recovering, was sent by them without delay to

Adalbert, Archbishop of Magdeburg, to be educated both in piety and learning. The Archbishop provided him with the ablest masters,

and at Confirmation, gave him his own name of Adalbert (or Albert). The noble pupil, in his progress in learning, outdid the highest

expectations of his spiritual father and master; but made piety his principal study. The hours of recreation he spent principally in

prayer, and in secretly visiting and relieving the poor and the sick.

After nine years, in 981, the Archbishop died, and our Saint returned to Bohemia, with a useful library which he had

collected. In 983, he received Holy Orders from Deithmar, Bishop of Prague. That prelate fell sick soon after, and drawing near

his end, cried out in a manner that terrified all the bystanders, saying that the devils were ready to seize his soul on account

of his having neglected the duties of his office – instead pursuing with eagerness the riches, honors, and pleasures of this world.

St. Adalbert, who had been present at that prelate's death in these sentiments, was not only terrified like the others,

but being touched with the liveliest sentiments of compunction for whatever he had done amiss in the former part of his life, put on

a hairshirt, went from church to church in the habit of a penitent imploring God's mercy, and dealt out alms with a very generous hand.

St. Adalbert's opposition proving ineffectual to prevent his election to the vacant see, he received episcopal consecration at the

hands of the Archbishop of Mainz, in 983. He entered Prague barefoot, and was received by Boleslas, Prince of Bohemia, and all the

people with great joy. His first care was to divide all the revenues of his see into four parts. He allotted the first to finance

the building, maintenance and ornamentation of his churches; the second to the support of his canons; the third to the relief of the

poor; reserving the fourth for himself and his household, in which he constantly maintained twelve poor men, in honor of the twelve

Apostles, and allowed provisions to a much greater number on festivals, besides employing his own patrimony in alms. He had in his

chamber a good bed upon which he never lay, preferring to take his short rest on a sackcloth or on the bare floor. His fasts were

frequent, and his whole life most austere. He preached almost every day, visited the poor in their cottages, and the prisoners in

their dungeons.

A great part of his diocese had continued till then involved in the shades of idolatry, and the rest were barbarians in

their manners, slaves to their passions, and Christians only in name. Finding them, by inveterate habits and long connivance,

incorrigibly fixed in their evil habits, he made a journey to Rome, and obtained from Pope John XV permission to retire in 989.

He visited the great Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino and put on the monastic habit, together with his brother Gaudentius,

at St. Boniface's in Rome. He took the last place in the monastery, and preferred always the lowest offices in the house.

After five years, the Archbishop of Mainz, in 994, urged the Pope to send him back to his episcopal see. His Holiness,

upon mature deliberation on the affair, ordered him to return; but declared him at full liberty to withdraw a second time, in case the

people continued disobedient and incorrigible as before. At his arrival in Prague, the inhabitants received him with great

acclamations, and readily promised an exact obedience to his directions, but proved as deaf to his admonitions as ever. Seeing himself

useless here, and only in danger of losing his own soul, he left them and preached the Gospel in Hungary, where he had previously

instructed their King Stephen, famous afterwards for his sanctity. At his return to his monastery in Rome, the Abbot Leo made him

Prior, in which station he behaved with his usual humility and condescension to the lowest in the house.

Emperor Otto III was so much delighted with his conversation, that he could scarcely bear having him out of his sight.

At the repeated solicitations of the Archbishop of Mainz, Pope Gregory V once more sent him back to his diocese. On the news of his

approach, the barbarous citizens, having at their head Boleslas, the wicked prince of Bohemia, massacred several of his relatives and

burnt their castles and towns. The holy Bishop, being informed of these outrageous measures, instead of proceeding on his journey to

Prague, went to his friend, another Boleslas, then Duke and afterwards the first King of Poland, who, after some time, advised him to

send deputies to the people of Prague, to know if they would admit him as their Bishop and obey his directives, or not. The message

was received with scorn, and they replied that there was too great an opposition between his ways and theirs for him to expect to live

in peace among them; that they were convinced it was not a zeal to reform them, but a desire to revenge the deaths of his relatives

that prompted him to seek re-admission; which, if he attempted, he might be assured of meeting with a very indifferent reception.

The Saint took this refusal and threat from his people for a sufficient reason to once again discharge himself from this

impossible burden, which made him direct his thoughts to the conversion of infidels, with which Poland and Prussia then abounded.

Having converted great numbers in Poland, he with his two companions, Bennet and Gaudentius, went into Prussia, which had not as

yet received the light of the Gospel, and made many converts at Danzig (the modern-day Gdansk). Being conveyed thence into a

small island (in the Baltic Sea), they were presently surrounded by the savage inhabitants, who loaded them with injuries.

One of them coming behind the Saint as he was reciting the psalms, knocked him down with the oar of a boat – upon which St. Adalbert

returned thanks to God, for thinking him worthy to suffer for the sake of his Crucified Redeemer.

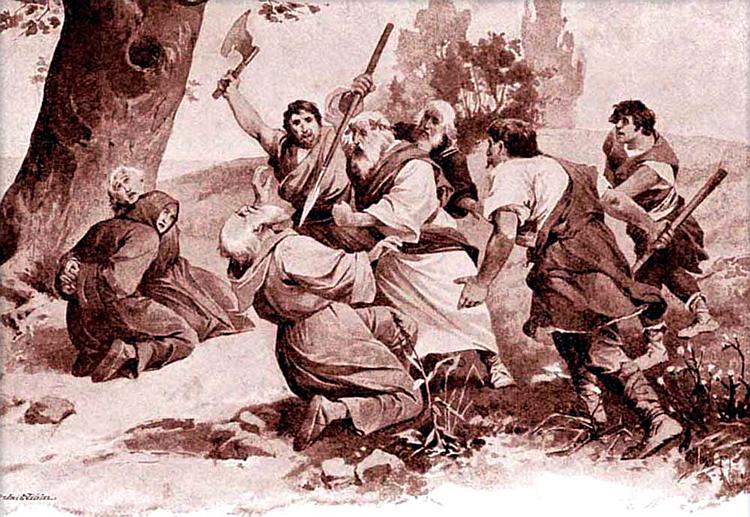

St. Adalbert and his companions attempted after this to preach the Gospel in another place nearby, but with no better

success; being told on their arrival that if they did not depart the next day, it would cost them their lives. They accordingly

withdrew in order to provide for their safety, and had laid down to take a little rest after their fatiguing journey, not realizing

they had been pursued. They were overtaken by a party of the infidels, by whom they were seized and bound, as victims destined for

a sacrifice. The Saint offered his life in ardent prayer, by which he begged of Him the pardon and salvation of his murderers.

The priest of the idols first pierced him in the breast with a lance, saying:

St. Adalbert and his companions attempted after this to preach the Gospel in another place nearby, but with no better

success; being told on their arrival that if they did not depart the next day, it would cost them their lives. They accordingly

withdrew in order to provide for their safety, and had laid down to take a little rest after their fatiguing journey, not realizing

they had been pursued. They were overtaken by a party of the infidels, by whom they were seized and bound, as victims destined for

a sacrifice. The Saint offered his life in ardent prayer, by which he begged of Him the pardon and salvation of his murderers.

The priest of the idols first pierced him in the breast with a lance, saying: You ought now to rejoice; for you had it always in

your mouth that it was your desire to die for Christ.

Six others gave him each a stab with their lances, and he died from these

seven wounds on the 23rd of April, 997 (image above). The heathens cut off his head and fixed it on a pole; his two companions they carried away

captives. Duke Boleslas of Poland bought the corpse of the Martyr at a great price, and translated it with great solemnity to the

Abbey of Trzemeszno, and from thence to Gniezno, where it is kept with great honor in the cathedral and has been rendered famous by

many miracles (image left). In the catalogue of the rich treasury of relics kept in the electoral palace of Hannover,

printed in 1713, mention is made of a portion of the relics of St. Adalbert in a precious shrine.

St. Adalbert is styled the First Apostle of Prussia, although he was only successful in planting the Faith in Danzig.

King Frederic II of Prussia, in his elegant memoirs of the House of Brandenburg published in 1758, tells us that the conversion of

the country of Brandenburg (the area around modern Berlin, about 200 miles southwest of ancient Prussia) was begun by the

conquests and the zeal of Charlemagne, and completed in 928, under Henry the Fowler, who again subdued that territory; that the

Prussians were originally Sarmatians – the most savage of all the northern idolaters; that they adored their idols under oak trees,

being strangers to the elegance of temples; and that they sacrificed enemy prisoners to their false gods. After the Martyrdom of

St. Adalbert, three Kings of Poland, all named Boleslas, attempted in vain to subdue them. Finally the Teutonic Knights conquered

that country in 1239, and planted Christianity therein. (It is almost incredible that at this late date, 13 years after the death

of St. Francis of Assisi, a sizeable portion of northern Europe was still pagan. Even in our modern times, the Mari people in Russia

still practice a form of paganism.)

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Back to Saints

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

He was born of noble parentage in Bohemia, in 956, and received at Baptism the name of Wojciech, which in the Slavic tongue signifies

Help of the Army. In his childhood his parents saw themselves in great danger of losing him by sickness, and in that extremity,

consecrated him to God by vow, before the altar of the Blessed Virgin, saying:

He was born of noble parentage in Bohemia, in 956, and received at Baptism the name of Wojciech, which in the Slavic tongue signifies

Help of the Army. In his childhood his parents saw themselves in great danger of losing him by sickness, and in that extremity,

consecrated him to God by vow, before the altar of the Blessed Virgin, saying:

St. Adalbert and his companions attempted after this to preach the Gospel in another place nearby, but with no better

success; being told on their arrival that if they did not depart the next day, it would cost them their lives. They accordingly

withdrew in order to provide for their safety, and had laid down to take a little rest after their fatiguing journey, not realizing

they had been pursued. They were overtaken by a party of the infidels, by whom they were seized and bound, as victims destined for

a sacrifice. The Saint offered his life in ardent prayer, by which he begged of Him the pardon and salvation of his murderers.

The priest of the idols first pierced him in the breast with a lance, saying:

St. Adalbert and his companions attempted after this to preach the Gospel in another place nearby, but with no better

success; being told on their arrival that if they did not depart the next day, it would cost them their lives. They accordingly

withdrew in order to provide for their safety, and had laid down to take a little rest after their fatiguing journey, not realizing

they had been pursued. They were overtaken by a party of the infidels, by whom they were seized and bound, as victims destined for

a sacrifice. The Saint offered his life in ardent prayer, by which he begged of Him the pardon and salvation of his murderers.

The priest of the idols first pierced him in the breast with a lance, saying: