A. Penance is characterized as the Sacrament of the remission of sins.

A. Penance is characterized as the Sacrament of the remission of sins. A. Penance is characterized as the Sacrament of the remission of sins.

A. Penance is characterized as the Sacrament of the remission of sins.

I. Penance is defined as a Sacrament in which the priest, in the place of God, forgives sins committed after Baptism to those sinners who are truly penitent, sincerely confess their sins, and are ready to make satisfaction for them.

By the word penance we understand either, as in the present case, the whole process necessary to obtain forgiveness of our sins, or only a part of it. Penance, in this latter sense, signifies sometimes sorrow for the sins committed; sometimes a change of sentiment or disposition, or the resolution to avoid sin in future; sometimes satisfaction for sin, or punishment imposed upon ourselves or freely accepted to satisfy the divine justice for our sins.

II. The proximate matter of the Sacrament of Penance are the acts of the penitent: contrition with the purpose

of amendment, confession, satisfaction. The sins themselves, inasmuch as they form the subject-matter of confession, are called the

remote matter. The form consists (essentially) in the words: I absolve thee from thy sins

(Council of Trent,

Sess. 14, can. 4).

The matter and form of a Sacrament are the elements which constitute the essence of the Sacrament. Now, the above-mentioned acts of the penitent and the absolution of the priest constitute the essence, or total sign, of Penance. The absolution is regarded as the form partly because, like the forms of the other Sacraments, it consists in words; but chiefly because it effects what it distinctly signifies or expresses – the forgiveness of sins. If, therefore, Christ gave to His Apostles and through them to the Church the power to forgive sins, as we shall immediately prove, the sign or ceremony by which this power is exercised is a true Sacrament.

B. Christ gave to His Apostles a special power to forgive sins.

Christ gave to the Apostles, not, as Protestants have asserted, merely the power to remit sin by the Sacrament of Baptism, not merely the power to declare to the faithful that their sins were forgiven them, provided they were truly contrite and aroused within themselves sentiments of faith and confidence. He gave them a special power to forgive sins committed after Baptism.

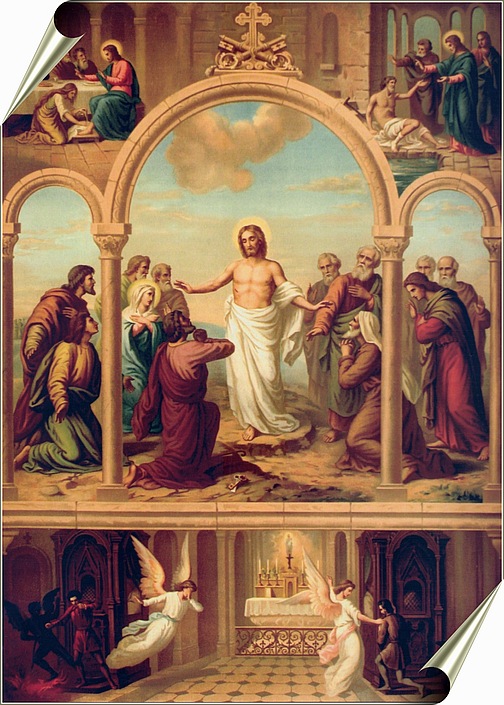

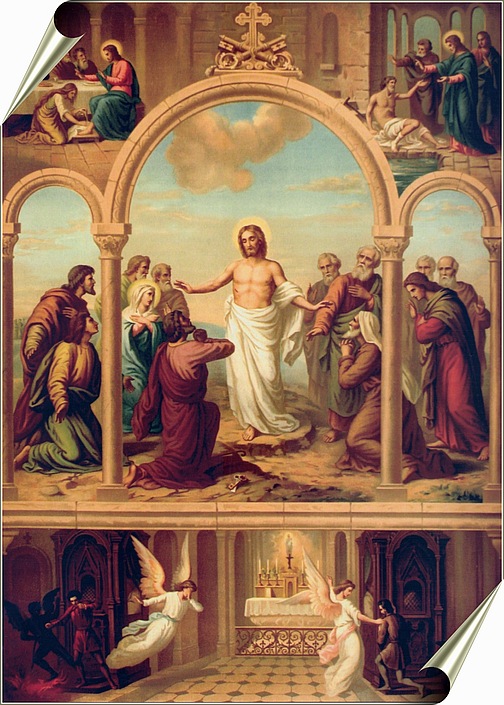

I. Christ, after His resurrection, breathed upon His Apostles, and said: As the Father hath sent Me I also send you...

receive ye the Holy Ghost; whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them; and whose sins you shall retain, they are retained

(John 20: 21-23).

a. Here there is evidently question of true forgiveness of sins, not of a mere declaration that they are forgiven.

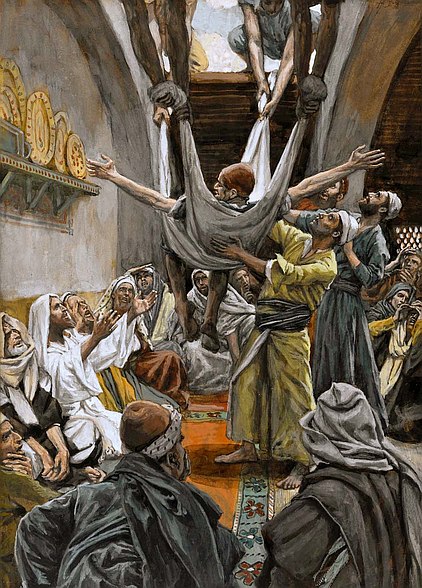

For Christ here used the same words that He employed elsewhere to signify real forgiveness of sins. Thus He spoke to the

paralytic:

a. Here there is evidently question of true forgiveness of sins, not of a mere declaration that they are forgiven.

For Christ here used the same words that He employed elsewhere to signify real forgiveness of sins. Thus He spoke to the

paralytic: Thy sins are forgiven thee

(image left) and emphatically declared on the same occasion that the Son of Man

hath power on earth to forgive sins

(Luke 5: 24). He sent His disciples as the Father had sent Him – with the same power.

Therefore, as Christ Himself had power to forgive sins, so did He confer this power on His Apostles. The Apostles received also the

power to retain sins; but this power would have been ineffectual if sins were forgiven by the acts of the penitent, not by the ministry

of the Apostles; for they could not prevent the faithful from eliciting those acts by which sin is remitted.

b. Christ here speaks not of the forgiveness of sins through Baptism; for the power He confers extends to the

forgiveness and retention of the sins of all; consequently, also the sins of the baptized. But it is obvious that the sins

of those already baptized cannot be forgiven anew by Baptism, since Baptism cannot be repeated; nor would the Apostles retain

the sins of the baptized if sin were forgiven by the renewal of the faith received in Baptism, as Luther maintained. Moreover,

Christ speaks of Baptism on another occasion, and in quite different terms (Matt. 28: 19). While Baptism is referred to in

connection with the preaching and propagation of the Gospel, no such restriction is made in reference to the power to forgive sins.

This power is also implied in the words: Whatsoever you shall bind on earth shall be bound also in Heaven; and whatsoever you shall

loose on earth shall be loosed also in Heaven

(Matt. 18: 18); with this difference, however, that the power of binding and

loosing here referred to is more comprehensive, and includes also legislative and coactive power (cf. Matt. 16: 19).

II. The power of forgiving sins as different from Baptism was from the earliest ages acknowledged as belonging to the Church. In the second century the Montanists were condemned for denying that the Church possessed the power to forgive mortal sins; and in the third century Novatus and his followers, who denied that this power extended to all mortal sins. The Oriental sects hold the doctrine of the Church in regard to the forgiveness of sins; which of itself is a sufficient evidence of its existence in the early Church.

C. This power of forgiving sins conferred on the Apostles is a judicial power.

I. To forgive and to retain sins (John 20: 21), to loose and to bind (Matt. 18: 18), are judicial acts; consequently, the power of forgiving and retaining sins, of binding and loosing, is a judicial power, constituting the Apostles judges in the true sense of the word.

As the secular judge according to circumstances acquits the accused of the crime laid to his charge, declaring him innocent, or leaves him under the charge, declaring him guilty, so the Apostles, according to the nature of the case, by their sentence were either to loose the sinner from the bonds of sin, by making him innocent and guiltless, or to leave him under the bond of sin and its penalty. The sentence of the spiritual judge, however, has greater efficacy, since it not only declares the penitent innocent, but confers innocence upon him. Nor would penance, in fact, be a Sacrament unless it effected that which it signifies.

II. The Church has always looked upon the power of forgiving sins as a judicial one, and in its administration observed a judicial form: accusation, absolution, delay or refusal of absolution, satisfaction or punishment; whence also jurisdiction is essential for the valid exercise of this power (Council of Trent, Sess. 14, c. 5).

D. Only the bishops and priests of the Church have inherited the power of forgiving sins.

I. The power of forgiving sins was to continue and to be exercised in the Church, not only during the lifetime of the

Apostles, but for all time. For (a) this power is contained in the mission given by Christ to His Apostles with the words:

I. The power of forgiving sins was to continue and to be exercised in the Church, not only during the lifetime of the

Apostles, but for all time. For (a) this power is contained in the mission given by Christ to His Apostles with the words:

As the Father hath sent Me I also send you

(John 20: 21). But the mission of the Apostles is to continue to the end of

time: Behold, I am with you all days, even to the consummation of the world

(Matt. 28: 20); consequently, also

the power to forgive sins. This is all the more evident from the fact that there will always be sinners who need reconciliation with

God. (b) It has always been the belief of the Church that the power to forgive sins conferred upon the Apostles was not an

extraordinary gratuitous gift belonging only to the early ages of the Church, but that it was an ordinary power given for all time.

Hence the Church always excluded from its fold those who denied this power to the successors of the Apostles, as was mentioned above.

II. Bishops and priests, the successors of the Apostles in the priesthood, have inherited this power. For (a) it is a Sacrament of the Church. But the bishops are the ordinary ministers of the Sacraments, as are also priests, unless an exception be proved, as in the case of Confirmation and Holy Orders. That priests are, in virtue of the priestly character, the ordinary ministers of the Eucharist, is a sufficient cause why they should likewise be ministers of the Sacrament of Penance. For this Sacrament is a preparation for the reception of the Holy Eucharist. Hence it is natural that those who possess the power of administering this Sacrament should also possess the power of preparing the faithful for its worthy reception. (b) It is a fact that for centuries, not only bishops, but also simple priests, administered the Sacrament of Penance.

For the valid administration of the Sacrament of Penance, not only the character of the priesthood but also

jurisdiction is required. For the Sacrament of Penance is essentially a judicial act, and can therefore be exercised only in

behalf of those who are subject to the jurisdiction of the judge or minister. The Council of Trent (Sess. 14, c.7) says:

Since the nature and existence of a judicial act requires that judgment be pronounced upon a subject, it was always the conviction

of the Church, and this synod confirms it as an undoubted truth, that absolution given by a priest to one over whom he has no ordinary

or delegated jurisdiction is null and void

. Ordinary jurisdiction is that connected with an office involving the ordinary

care of souls – for instance, that of a bishop over his diocese, or of a parish priest over his parish. A delegated jurisdiction

is that of one not holding such an office, yet duly empowered to administer the Sacrament of Penance. Hence the Fourth Lateran Council

ordered that the faithful should confess once a year to their own priest, that is, to a priest invested with jurisdiction.

As may be shown from numerous documents, the Greek Church as well as the Latin always believed that, besides the priestly character, jurisdiction was necessary for the valid administration of the Sacrament of Penance. A priest invested with ordinary jurisdiction, however, cannot without special faculties absolve from reserved cases, the absolution of which either the Pope or the bishop may have, for good reasons, reserved to himself. The Church can give jurisdiction to a priest in a greater or a lesser extent, and, consequently, except some cases or persons from his jurisdiction altogether; as also the jurisdiction of a secular court may be sometimes limited. In danger of death, however, every priest is empowered to absolve all persons from all cases.

III. Only bishops and priests have the power to forgive sins. It was to the Apostles and their successors in the

priesthood alone that Christ addressed Himself when He conferred this power on His Church (John 20: 21); they alone were

constituted by Him the dispensers of the mysteries of God

(1 Cor. 4: 1).

E. The power to forgive sins in the Sacrament of Penance extends to all sins committed after Baptism.

E. The power to forgive sins in the Sacrament of Penance extends to all sins committed after Baptism.

I. The words by which Christ gave His Apostles this power are of a general nature, admitting of no exception:

Whose sins you shall forgive they are forgiven them.

The Apostle St. Paul in fact remitted the sins of a Corinthian

public sinner, who was guilty of a most grievous crime (2 Cor. 2: 10).

The clear evidence of the Scriptures cannot be weakened by certain obscure expressions which seem to convey that some

sins cannot be forgiven. In reference to such passages suffice it to remark that nowhere is the impossibility on the part of God

to forgive sins asserted; it may, however, be impossible on the part of the sinner, and is impossible as long as he remains

impenitent and resists all external and internal graces. It is in this sense that we are to understand the words addressed by Our Lord

to the Pharisees, who asserted that His miracles were the work of the devil: A sin against the Holy Ghost will not be forgiven

(Matt. 12: 31). In other passages in which conversion is said to be impossible we are to understand not a strict impossibility,

but a difficulty which, owing to the perversity of the sinner, will rarely, if ever, be overcome.

II. The Church has always taught that every sin without exception can be remitted in the Sacrament of Penance, and condemned as heretics those who asserted the contrary, as we have seen above.

F. The Sacrament of Penance is the ordinary means of salvation for those who after Baptism have fallen into mortal sin.

I. As Baptism is a necessary means of salvation for all, so the Sacrament of Penance is a necessary means of salvation for those who have fallen into mortal sin after Baptism.

a. We must regard as a necessary means of salvation a sacrament instituted by God for the remission of those sins which exclude men from his last end. But such is the Sacrament of Penance; for its minister has received the power not only to remit, but also to retain sins, and his sentence in either case is ratified in Heaven. The Sacrament of Penance, therefore, is a means instituted by God for the forgiveness of sins committed after Baptism; and as for the unbaptized there is no forgiveness without Baptism, so for those who have fallen into grievous sin after Baptism there is no forgiveness except by the Sacrament of Penance. This necessity follows also from the fact that Penance is instituted under the form of a tribunal; for, as public criminals cannot evade the secular, neither can sinners evade this spiritual tribunal instituted by Christ.

b. The Council of Trent (Sess. 14, can. 2) teaches that Penance is as necessary for those who have fallen into mortal sin after Baptism as Baptism is for the unbaptized. But Baptism is necessary for the unbaptized as a means of salvation; therefore also Penance for those who have fallen after Baptism.

II. Penance is only the ordinary means of salvation for the fallen, and can, therefore, for the reasons stated in the article on Baptism, be substituted by perfect contrition. This contrition, which proceeds from a perfect love of God, includes the will to do all that is necessary for salvation; consequently, to receive the Sacrament of Penance, if and when possible. Mortal sins, however, which have been thus forgiven through perfect contrition must afterwards be submitted to the Church's tribunal in the Sacrament of Penance, in the same manner as one who has been reconciled with God by the baptism of desire is not exempted from the grave obligation of receiving the Sacrament of Baptism.

Besides the sins themselves, Penance also remits the eternal punishment due to mortal sin. It restores sanctifying grace if lost, and increases it if it already exists. In fact, sin is remitted by the infusion of sanctifying grace; whence it follows that the same sin may be repeatedly submitted to, and be effectually absolved by, the power of the keys. For in each absolution of a sin sufficient grace is infused to cancel its guilt. Another fruit of Penance is that peace of soul which gives to the reconciled sinner strength in temptation and courage to brave all the difficulties of salvation. Penance, finally, not only delivers the sinner from his sins, but also preserves him from relapse (Council of Trent, Sess. 14, c.3).

G. The power of forgiving sins granted to the Church implies the necessity of self-accusation on the part of the sinner; whence confession is of divine origin.

Father, I have sinned against Heaven and before thee...

(Luke 15:18).

I. The power of forgiving sins bestowed on the Apostles is a judicial power and its exercise is a judicial act. A judicial act necessarily supposes that the judge is cognizant of the case in which he is to pronounce sentence. But the matter on which he is to pronounce the sentence is sin; therefore he must know the sin or sins of the penitent. But how is he to know them? Though in some cases he may possibly obtain a knowledge of them from others, yet this cannot always be the case, nor can this be the manner of process intended by Christ. For while secular tribunals pass judgment only on certain actions which are public, the most secret thoughts and desires, not merely external actions, form the subject-matter of the tribunal of Penance. But internal thoughts and desires can be learned only be self-accusation. Self-accusation was, therefore, intended by Christ. Besides, in all tribunals some punishment is inflicted on the guilty as an atonement, which must be in some way proportioned to the offence. But how could a judge inflict a punishment proportioned to the offence unless he had cognizance of the offence itself? And how is he to obtain this necessary information unless by the self-accusation of the penitent?

II. From the different monuments of tradition it is manifest that confession has always been in use in the Church of God, and has been considered necessary for the forgiveness of sins.

As in other doctrines, so also in regard to confession, those Oriental sects who apostatized from the Church in the early ages agree with the Roman Church in the doctrine of confession; which alone suffices to prove that the obligation of confession was not first imposed by Pope Innocent III in the Fourth Council of the Lateran, as some Protestants assert. Pope Innocent did enforce the obligation of confessing at least once a year. And, in fact, it would have been impossible for any pope to introduce such an innovation without encountering the strongest opposition on the part of the Church. But of such an uproar there is no trace in Church history.

Confession is mentioned also in the ancient councils. One held at Rheims (625) prescribes that during Lent no

priest except their own pastor was to hear the confessions of the faithful. In early historical records, particularly in the

lives of the Saints, we find frequent mention of confession. Sometimes it is described with what humility the Saints themselves

confessed their sins in order to obtain absolution; sometimes how they administered this Sacrament to others. Pope Leo I † 461 rebuked

certain bishops for compelling sinners, contrary to the apostolic canons, to confess all their sins publicly, as private confession to

the priest was sufficient (ep. 168 ad episcop. Campan.). The Fathers of the Church frequently speak of confession.

Thus St. Gregory the Great (hom. 26 in Evang.) says: Christ said to Lazarus: Come forth – as if He addressed Himself to one

dead in sin and said: Why hidest thou thy guilt in thy conscience? ...Let the dead man, then, come forth; let the sinner confess his

guilt. After he [the sinner] has come forth, the disciples loose him, when the pastors of the Church absolve Him from the punishment

he deserved, because he is not ashamed to confess his deeds.

St. Augustine (Serm. 392 [al. 49]) says: We must

confess our sins to those who are appointed the dispensers of the divine mysteries.

Similar passages are to be found in the

writings of the earlier Fathers and ecclesiastical writers – Origen, St. Cyprian, Tertullian, St. Irenaeus. The author of the work

entitled The Doctrine of the Twelve Apostles (first century) writes: In the assembly of the faithful confess thy sins;

and come not to thy prayer with a bad conscience.

III. The Council of Trent (Sess. 14, can. 6) defined the doctrine of the Church on confession against the innovators

of the sixteenth century. If anyone deny that sacramental confession is of divine institution, or that it is not necessary for

salvation: let him be anathema.

It was altogether in keeping with the divine wisdom and with the perfection of the Christian religion that confession should be made a condition of obtaining forgiveness of sin. For, in the first place, it gives relief to the sinner; for, as we know from experience, nothing relieves the burdened heart more than to communicate its troubles to a trusted friend. Regarded from a supernatural standpoint, the self-abasement attending confession cannot fail to be productive of abundant graces. Confession, moreover, preserves us from relapsing into sin, partly because the confessor prescribes suitable remedies for us, partly because the necessity of undergoing the shame of self-accusation strengthens us in temptation. Finally, confession is of the greatest advantage to the family, and to society at large. It secures the right of property by enforcing honesty and the restitution of ill-gotten goods; it checks sinful relations, since the confessor must insist on the necessity of avoiding the proximate occasions of sin, even under the denial of absolution. Society at large finds a powerful support in confession for the maintenance of morality and the restraint of the most dangerous human passions. We may, therefore, easily understand why even under the Old Law sin-offering, and by this very fact confession of sin, was prescribed (Lev. 5: 6-7).

H. The acts of the penitent – contrition, confession, and satisfaction – in order to be valid matter of the Sacrament of Penance, must be endowed with certain qualities.

I. Contrition is a detestation of, and sorrow for the sins committed, combined with the firm purpose to sin no more.

The necessity of contrition is inculcated in all those passages of Scripture wherein the sinner is exhorted to do penance in order to

obtain pardon of his sin. Rend you hearts, and not your garments

(Joel 2: 13). Do penance... for the remission of your

sins

(Acts 2: 38). If the sinner is to be converted, to return again to God, he must turn away with horror from that which

separates him from God; he must have true sorrow for that which is the greatest of evils, and makes him hateful to God. By this sorrow

and detestation he crushes, as it were, the innate pride contained in every revolt against God; whence the names contrition and

attrition.

Contrition must include the purpose of amendment – the earnest will to amend one's life and sin no more; for what one hates and detests he likewise shuns and flees. Purpose of amendment, therefore, includes also the will to avoid the proximate occasion of sin, i.e., every occasion in which one is likely to sin. For he who desires the end desires also the means; therefore he who wishes to avoid sin will, as a necessary means, also avoid the proximate occasion.

The sorrow, or contrition, for sin required for the worthy reception of the Sacrament of Penance, and also the purpose of amendment, must be: (a) internal and sincere; (b) universal, i.e., it must extend at least to all mortal sins; for as long as the heart clings to one mortal sin, or is not determined to avoid all mortal sins, it cannot turn to God. It is not necessary, however, explicitly to elicit sorrow for every sin in particular, since each sin is contained in all. As contrition is absolutely necessary for the Sacrament of Penance, its reception would be invalid, and consequently sacrilegious, without it. This is also the case with a confession of only venial sins, if one is sorry for none of them. Hence it is advisable for those who have only venial sins to confess since their last confession to add one or more sins already confessed for which they are truly sorry; (c) contrition must be supernatural, i.e., it must proceed from grace, and rest on the supernatural motives of faith. Such motives are the loss of sanctifying grace and of the friendship of God, the fear of Hell or Purgatory, not the merely natural consequences of sin (e.g., the loss of temporal goods, loss of reputation, loss of health, etc.)

Supernatural contrition may be either perfect or imperfect (the latter is called attrition), according as the motive from which one detests and abhors sin as the greatest evil is the love of God for His own sake – perfect; or merely the fear of the punishments due to sin – imperfect. Contrition, though proceeding from the most perfect motive of the love of God, may, however, be imperfect, if it is not efficacious to make us detest sin as the greatest evil. Hence contrition may be perfect in its motive but imperfect in its efficacy. On the other hand, contrition which is imperfect in its motive (e.g., more from the fear of punishment than from the love of God) may be perfect in its efficacy as far as the detestation of sin as the greatest evil is concerned, but not in the sense that it suffices of itself for the justification of the sinner (which comes from the motive of the love of God).

Perfect contrition is not required for the valid reception of the Sacrament of Penance. For, since perfect

contrition is sufficient of itself for the remission of sin, if it were still necessary for the worthy reception of the Sacrament,

the Sacrament would only increase sanctifying grace, but never confer the first grace upon the sinner, and therefore could never

have the efficacy given to it by Christ. For, as Baptism is the Sacrament which confers supernatural life, so Penance is that

which restores this supernatural life if lost. Therefore the Council of Trent (Sess. 14, c. 4) teaches that Imperfect

contrition, though it cannot of itself, without the Sacrament of Penance, justify the sinner, yet it disposes him to receive divine

grace in the Sacrament of Penance.

With regard to the preparation for justification in general, the same Council (Sess. 6, c.6)

teaches that sinners are disposed to obtain justification in Baptism while they turn from the fear of God's justice to the

consideration of His mercy, conceive hope, and thus begin to love God as the source of all justice.

But such disposition does

not include perfect contrition; therefore perfect contrition is not required as a disposition for the Sacrament of Penance.

The Confessional of St. Jean-Marie Vianney.

II. Confession must be (a) entire; i.e., it must extend to all mortal sins, according to their number

and species. If anyone assert that in the Sacrament of Penance it is not necessary, by divine institution, for the remission

of sins, to confess each and every mortal sin which one can remember after due and careful examination, also secret sins and those

against the two last Commandments of God, and those circumstances which alter the nature of a sin; let him be anathema

(Council of Trent, Sess. 14, can. 7). As the confessor is to pass judgment he must have cognizance of the nature of the sin

of which he has to judge. The nature of a sin is determined by the species to which it belongs. Sins against the same

Commandment may belong to different species. The confessor must also know the number of sins; for the number greatly influences

the sentence of a judge. God, however, does not exact impossibilities, and, consequently, when completeness is hardly possible it is

sufficient to give the probable number since the last good confession, or within a given time (e.g., about so many times per week,

or per day). Confession must be (b) sincere, i.e., the penitent must have the will to confess all those sins which he knows

that he is bound to confess. By this sincerity or good-will, confession, even though it may not be materially complete –

actually extending to each and every sin – is formally complete, i.e., extending to the number and species of one's sins as far

as it is morally possible under the circumstances. A sincere confession becomes a comparatively easy matter from the fact that the

confessor is bound by the strictest laws, both divine and human, to the most rigid secrecy by the seal of

confession. Finally, confession must be clear, so as to be intelligible to the confessor; otherwise he cannot gain the necessary

knowledge of the facts.

If a confession happens to be incomplete without being invalid, as, for instance, when a mortal sin has been forgotten without grave carelessness, it is sufficient to mention the sin omitted in the next confession. But if the confession is invalid; for instance, if one should conceal a mortal sin from shame or purposely accuse oneself without sufficient clearness, it would be necessary to repeat the whole of that confession, together with the following confessions made with the consciousness of the invalidity of the first – in other words, a general confession is necessary. A general confession may be profitable also at other times, as it gives greater security to the state of one's conscience.

III. Satisfaction (commonly called penance) is the performance of certain penitential works imposed by the

confessor, partly as a remedy against relapse and a means of amendment, but chiefly as a punishment for sin. For God

does not always remit the temporal punishment with sin itself and the eternal punishment, as is manifest from the words of the prophet

Nathan to David: The Lord also hath taken away thy sin; nevertheless, because thou hast given occasion to the enemies of the Lord

to blaspheme, for this thing the child that is born of thee shall surely die

(3 Kings 12: 13, 14). Besides, it is in

accordance with the justice of God to demand of us some penal satisfaction for our rebellion against Him and for our sinful attachment

to His creatures, and also to deter us by the dread of punishment from relapsing into sin. Hence the confessor as a judge has the

power and the obligation to impose satisfaction for sin. Thus he exercises the power of binding, conferred on him by Christ.

Although the penitent is bound to accept and perform the penance enjoined, yet its non-performance does not render the Sacrament

invalid or fruitless, provided only the penitent had the intention to perform it.

I. The duty of satisfaction is facilitated by indulgences granted by the Church.

An indulgence is a remission of temporal punishment due to sin after the sin itself has been remitted, granted

outside the Sacrament of Penance. In the Sacrament of Penance the temporal punishment is commuted into a lighter penance; by indulgence

it is remitted – not simply, however, but by the application of the satisfactions of Christ and of the Saints entrusted to the Church's

keeping.

An indulgence is a remission of temporal punishment due to sin after the sin itself has been remitted, granted

outside the Sacrament of Penance. In the Sacrament of Penance the temporal punishment is commuted into a lighter penance; by indulgence

it is remitted – not simply, however, but by the application of the satisfactions of Christ and of the Saints entrusted to the Church's

keeping.

I. There exists in the Church a real deposit or treasury of the satisfactions of Christ and of the Saints. Every good work has a twofold value – one of satisfaction and of merit – as also the actions of Christ had an expiatory and a meritorious value. Now, the satisfactions of Christ were superabundant; and the Saints, who, it is true, received a reward commensurate with their merits, do not themselves need all the satisfactory value of their good works and sufferings. Thus the Blessed Virgin did not require any satisfaction, since She had no sin to atone for. Other Saints required but little; the remainder of their satisfactions is superabundant. Now, these superabundant satisfactions are the common possession of the Church, and form what is called the treasury of the Church.

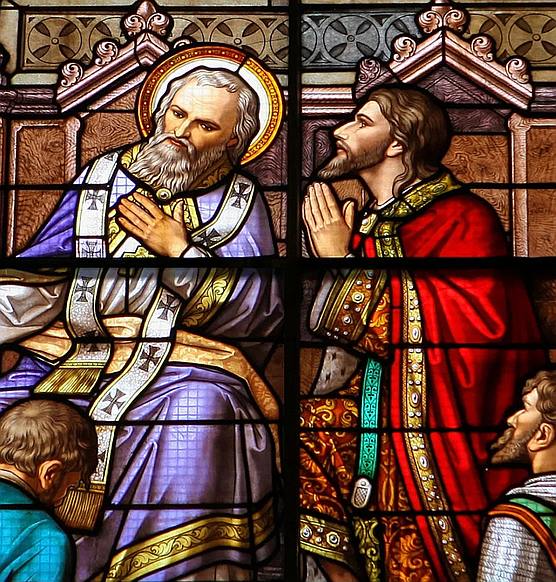

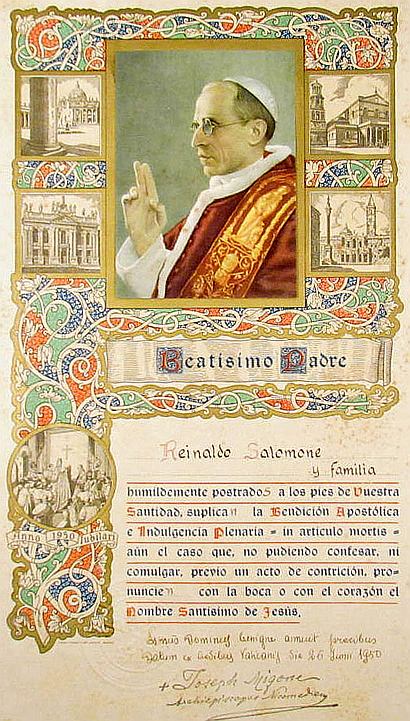

II. The Church – in the first instance the Pope, its Supreme Head – has power to apply these satisfactions to individuals

(image right), and thus to remit the temporal punishment due to sin. Whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth, it shall be loosed

also in Heaven

(Matt. 16: 19). By reason of their generality we must understand these words to refer to every bond or

obstacle which bars Heaven against the faithful, consequently to the outstanding temporal punishment of sin. If an offended person

agrees to accept satisfaction of a third party in lieu of the offender, his right is not thereby violated. That God has agreed to accept the

satisfaction of a third party – of Christ and of the Saints – may be inferred: (a) from the extent of the power conferred

by Him on His Church; (b) from the existence of the treasury of the Church, which may be thus applied; (c) from the

nature of the work of our redemption, which is essentially a work of mediation.

III. The Church always exercised this power. To whom you have pardoned anything, I also; for what I have pardoned,

if I have pardoned anything for your sakes, I have done it in the person of Christ

(2 Cor. 2: 10). When St. Paul,

in the person of Christ, condoned punishment to the guilty Corinthian here referred to, his condonation was certainly ratified by God.

It was, therefore, not a question of absolution from excommunication, but from the temporal punishment, if such was still due; for the

Apostle doubts whether there was anything to pardon – that is, whether the sinner himself had not already rendered sufficient

satisfaction to God's justice. As we learn from the writings of St. Cyprian †258 (ep. 14, ad clerum., n. 2), from the earliest

times ecclesiastical penances were shortened at the prayers of the martyrs, in the belief that this commutation was ratified in

the sight of God. This is also proved by the fact that Tertullian (de pud., c. 22), after his apostasy in the beginning of the

third century, reproached the Church with granting a remission of punishment in consideration of the satisfactions of the martyrs.

A partial indulgence (for instance of 7 years or 40 days) does not imply merely the remission of a certain canonical penance (e.g., of 7 years or 40 days) according to the former discipline of the Church, but the remission before God of so much of the temporal punishment due to sin as would be expiated by a certain public penance (e.g., of 7 years or 40 days). A plenary indulgence, on the other hand, is the remission of all the temporal punishment due to the sins which has been already remitted. A jubilee indulgence is a plenary indulgence of a more solemn character, connected with certain privileges and special faculties for the absolution from reserved cases. Indulgences are applicable to the souls in Purgatory, by way of intercession, when the Church so grants.

What has been said suffices to prove what the Council of Trent (Sess. 25, decret. de indulg.) teaches – that the use of indulgences is most salutary for the Christian people, and that the Church has the power to grant them. Indulgences are salutary not only because they remit the temporal punishment due to sin, but also because they encourage sinners to become reconciled to God, and promote the frequentation of the Sacraments and the practice of good works. If at times almsgiving is prescribed as a condition for gaining an indulgence, the indulgence is in that case no more purchased for money than Heaven is purchased by any other alms given with a view to eternal salvation.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com