On a precipice above a labyrinthine valley, in a region called Quercy, in the diocese of Cahors in France – about half-way between Limoges to the north and Toulouse to the south – stands one of Christendom's earliest shrines, which in the Middle Ages was among those (such as Notre Dame de Puy, Our Lady of El Pilar, and Our Lady of Montserrat) which were surpassed in importance only by the Holy Land, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela. Critical historians date the shrine only from the twelfth century, but a plethora of legends strongly argue in favor of a much greater age.

The name Rocamadour (or Roc-Amadour) is said to be the local dialect for Rock (or cliff) of Amator

–

Amator being Latin for he who loves,

or someone known for the virtue of charity. But more frequently, documents put the whole name

in Latin – Rupis Amator – which would denote, he who loves rock(s)

; in other words, a hermit who chose to live on a cliff,

amongst the rocks. This hermit, whose body was discovered in 1166, is honored as St. Amator, believed to be the founder of the Shrine.

The most common legend concerning this Saint identifies him with Zacchaeus – the publican mentioned in the Gospel of St. Luke,

who was converted by Our Lord.

The Bollandists – a society founded in the 17th century, consisting mostly of Jesuits, for the purpose of collecting the most reliable Acta Sanctorum (Acts of the Saints) – included in their volumes the Acts of St. Amator. Strangely enough, these acts do not actually describe the Saint as the Zacchaeus of the Gospel, but only a Hebrew by that name, who lived a pious and just life, waiting for the coming of the Messiah. The legend, in summary, states he was married to St. Veronica; the two of them were convinced that Jesus was the Messiah and became devoted servants of Jesus and Mary, even unto the time of Mary's Assumption into Heaven. But after the martyrdom of St. Stephen, they fled the Holy Land into France. Eventually Zacchaeus became known as Amator, and established a small chapel where he enshrined a small image (on home page) of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Child Jesus. The place became known as Rocamadour.

It must be admitted that this legend contains some evident contradictions. First, it contradicts the universal tradition that the Holy Family chose to live in poverty and had no servants. The Blessed Virgin may have had companions who helped Her in Her final years – but therein lies another contradiction. Her glorious Assumption into Heaven happened many years after the martyrdom of St. Stephen. Therefore the saintly couple could not have both served the Blessed Virgin until Her Assumption and also fled into France years before. The age of this legend is not known for certain, but it appears that the idea that St. Amator was Zacchaeus the publican must have come later. Obviously the legend related by the Bollandists is impossible to reconcile with this idea. The Zacchaeus of the Gospel was a notorious sinner who offered to give half his goods to the poor in reparation, and to restore anyone he had defrauded four-fold. He could not be said to have been a just and pious Hebrew, waiting for the coming of the Messiah.

Rocamadour is not the only place claiming to have the relics of Zacchaeus – the town of Levroux, about 50 miles southeast from Tours, possesses the relics of St. Sylvanus (or Sylvain), who is also believed to be Zacchaeus. He became known as Sylvanus (Latin for forest-dweller) because he chose to be a hermit in the forest.

There is another St. Amator (or Amateur) in France – the saintly Bishop of Auxerre, who died in 418. A curious discovery also

adds to the confusion over the identity of the Saint of Rocamadour. St. Didier, who was bishop of Auxerre from 596 to 614, translated the

relics of St. Amator to the monastery of St. Amans in Coronzac, on the occasion of the funeral of his mother. This monastery was destroyed

by raiding Saracens soon after. Amidst the ruins, the tomb of St. Didier's mother was eventually found, with a lengthy inscription claiming

that the relics of St. Amator were hidden by the monks, before the invasion, at Rocamadour! The inscription also claims that the place

received its name from this St. Amator, and that the Acts of St. Amator calling him Zacchaeus are fictions of a

deluded antiquity

(delusa vetustas).

It is not our purpose to either prove or disprove any of these legends, and we do not in any way wish to imitate those modernists

who entirely dismiss any legend which seems to have some historical problem. It is our purpose to show that the very existence of these

seemingly contradictory legends point to the existence of a person from one of the earliest ages of Christianity. For in denying the veracity

of the Acts of St. Amator, the mysterious inscription mentioned above confirms that these legends are from antiquity.

The greatest historian of Christian antiquity, Eusebius, has said nothing about the later life of Zacchaeus. Several early Fathers say he became

a bishop; some say the bishop of Caesarea in Palestine. Clement of Alexandria †217 says that many in his time thought that Zacchaeus was the same

person as the Apostle St. Matthias – the one chosen to take the place of Judas. The great mystic, Anna Catherine Emmerich, gives us little

information about the later life of Zacchaeus – only that he was one of the first disciples to be ordained to the priesthood after Pentecost.

However, Sister Emmerich does give some information about St. Veronica, which may provide a clue to the identity of St. Amator. Amongst the

narrations of her countless visions provided by Clemens Brentano, one reads that St. Veronica was really named Seraphia. Her husband was Sirach,

a member of the Sanhedrin, who was at first inimical to Our Lord, but later joined Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea in defending Him.

Seraphia became known as Veronica on account of the veil which she gave Our Lord to wipe His face during the Way of the Cross. This veil became

known as the true image (in Latinized Greek – vera icon) or simply as the Veronica. One of Seraphia's sons became a disciple

of Our Lord; his name was Amandor! In many ancient documents we find diverse spellings for Amadour – one of them is Amandour.

The greatest historian of Christian antiquity, Eusebius, has said nothing about the later life of Zacchaeus. Several early Fathers say he became

a bishop; some say the bishop of Caesarea in Palestine. Clement of Alexandria †217 says that many in his time thought that Zacchaeus was the same

person as the Apostle St. Matthias – the one chosen to take the place of Judas. The great mystic, Anna Catherine Emmerich, gives us little

information about the later life of Zacchaeus – only that he was one of the first disciples to be ordained to the priesthood after Pentecost.

However, Sister Emmerich does give some information about St. Veronica, which may provide a clue to the identity of St. Amator. Amongst the

narrations of her countless visions provided by Clemens Brentano, one reads that St. Veronica was really named Seraphia. Her husband was Sirach,

a member of the Sanhedrin, who was at first inimical to Our Lord, but later joined Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea in defending Him.

Seraphia became known as Veronica on account of the veil which she gave Our Lord to wipe His face during the Way of the Cross. This veil became

known as the true image (in Latinized Greek – vera icon) or simply as the Veronica. One of Seraphia's sons became a disciple

of Our Lord; his name was Amandor! In many ancient documents we find diverse spellings for Amadour – one of them is Amandour.

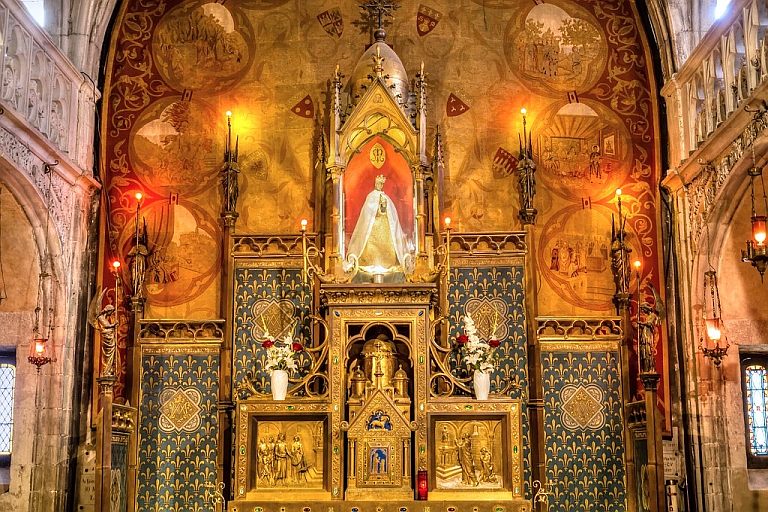

Unfortunately the shrine of Rocamadour was devastated by Protestants in 1592 and the relics of St. Amator burned. However, a few fragments remained and were later enclosed in a new reliquary (image right). Nonetheless, it appears that the ancient statue of Our Lady survived. The statue is a small carving in dark oak – crude in appearance; but this is typical for religious images of great antiquity. Apparently this statue was at one time somewhat beautified by silver leaf and some colored pigments. Traces of both are found on the statue, attesting to its authenticity. Crude or not, the tradition is that St. Amator built his oratory specifically for this image of Our Lady, and Rocamadour has always been considered to be principally a Marian Shrine.

The little statue of the Blessed Virgin, Our Lady of Rocamadour, resembling those which the ancient Christians of Gaul venerated in the hollows of oak trees, was the instrument of miracles in favor of the fervent pilgrims who came to invoke her in Her rocky sanctuary. The pilgrims multiplied, and soon became so frequent, that a town was built at the foot of the holy place. This town, situated in a desolate region, on a spot unproductive, and one of the most difficult of access at first, became nevertheless, thanks to the devotion of our ancestors, one of the principal towns of Quercy.

Historians tell us that a pre-existing church at Rocamadour was given over to the care of the Benedictine Monastery of Tulle in 968 by

the Bishop of Cahors. In spite of this fact, modern critics insist that pilgrimages to Rocamadour did not begin until after the discovery of the

body of St. Amator in 1166. But numerous authors tell a different story. The Abbé Orsini in his Life of the Blessed Virgin, English translation –

1856, says:

Historians tell us that a pre-existing church at Rocamadour was given over to the care of the Benedictine Monastery of Tulle in 968 by

the Bishop of Cahors. In spite of this fact, modern critics insist that pilgrimages to Rocamadour did not begin until after the discovery of the

body of St. Amator in 1166. But numerous authors tell a different story. The Abbé Orsini in his Life of the Blessed Virgin, English translation –

1856, says: This pilgrimage to Our Lady of Rocamadour was celebrated even in the time of Charlemagne; the famous knight-errant Roland, nephew of

this Emperor, came to Rocamadour in 778. He offered to the Blessed Virgin a gift of silver of the weight of his sword, and after his death in the

fields of Roncevaux, this sword was brought to Rocamadour. It is said the sword, Durandal, can still be seen there.

(Image left.)

Zsolt Aradi in his Shrines to Our Lady Around the World, 1954, says of Rocamadour: Charlemagne, on his way to battle the Moors

in Spain, is supposed to have visited this shrine. There is ample historical evidence that large parts of the population of Spain and France considered

Our Lady of Rocamadour as their protectress, especially those who journeyed as pilgrims to the famous Shrine of St. James the Apostle at Compostela

in Spain, and encountered Our Lady of Rocamadour on the way during this trip.

It should be noted that Rocamadour was not really on the way

to Compostela – rather it was considerably out of the way, and in very rugged terrain. Aradi continues: 216 steps (earlier documents give the

number as 278) lead from the valley up to the Shrine and Basilica. Pilgrims climb these on their knees. Charlemagne, St. Louis King of France,

Henry II King of England, are believed to have climbed these stairs.

Even before the discovery of St. Amator's body in 1166, the great St. Bernard visited this Shrine in 1147; King Henry II of England, accompanied by the future St. Thomas Becket, visited in 1159. Henry returned in the year 1170, according to Roger de Hoveden, to fulfill a vow, which he had made to the Blessed Virgin in a long illness. As the lands bordering upon Quercy had no great liking for the Englishman, the island monarch protected himself with a small army to make this pious voyage. Henry left marks of his munificence at the church of Our Lady, and with the poor of Rocamadour.

In 1212 at the battle of Las Novas de Tolosa (one of the principal battles for the reconquest of Spain from the Moors), the Christian soldiers were said to be at the point of yielding when they brandished a standard with a picture of Our Lady of Rocamadour, causing the Muslim enemy to flee – according to the chronicle of Trois-Fontaines Abbey.

In the number of illustrious pilgrims, who came to honor Mary in Her mountain sanctuary, is reckoned Simon de Montfort, legate of the Pope; Arnauld Amalric, who was afterwards Bishop of Narbonne; Saint Louis, accompanied by his three brothers, by Queen Blanche of Castile, and Alphonsus, Count of Boulogne, who ascended the throne of Portugal; King Charles the Fair, King John, Louis XIl, and a multitude of nobility.

Among the great bishops who visited, at different times, the miraculous chapel of Our Lady, we find one name so dear to literature,

to humanity, and to Catholicism, that we cannot leave him among the crowd. This name, by which France considers herself honored, and which commands

the respect even of impiety itself, is that of François Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai. Devoted from his cradle to Our Lady of Rocamadour, by his pious mother,

Fenelon came more than once to pray, in the depths of Quercy, to Her who had given him the courageous wisdom which he employed so nobly in the instruction of kings.

Two pictures, hung up as votive offerings, in the sanctuary of Mary, represent two solemn phases of his existence. In the first, he is newly-born, and sleeps in

his cradle; in the second, being a young man, and already a doctor, he comes to pay homage to this divine Protectress, for the first success of his rising genius.

At some distance is a tomb, over which he wept and prayed later on – that of his mother, whose wish was to sleep her last sleep in the shadow of the altar of

Our Lady of Rocamadour.

Among the great bishops who visited, at different times, the miraculous chapel of Our Lady, we find one name so dear to literature,

to humanity, and to Catholicism, that we cannot leave him among the crowd. This name, by which France considers herself honored, and which commands

the respect even of impiety itself, is that of François Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai. Devoted from his cradle to Our Lady of Rocamadour, by his pious mother,

Fenelon came more than once to pray, in the depths of Quercy, to Her who had given him the courageous wisdom which he employed so nobly in the instruction of kings.

Two pictures, hung up as votive offerings, in the sanctuary of Mary, represent two solemn phases of his existence. In the first, he is newly-born, and sleeps in

his cradle; in the second, being a young man, and already a doctor, he comes to pay homage to this divine Protectress, for the first success of his rising genius.

At some distance is a tomb, over which he wept and prayed later on – that of his mother, whose wish was to sleep her last sleep in the shadow of the altar of

Our Lady of Rocamadour.

Sometimes it was not merely isolated pilgrims, but cities and provinces in a body, who repaired to Rocamadour. In 1546,

says M. de Malleville,

in his Chronicles of Quercy, on the 24th of June, the day and Feast of the Blessed Sacrament and of Saint John, was the great pardon of Rocamadour.

The concourse of people of the kingdom, and of foreigners, was so great, that several persons, of all ages and of each sex, were smothered up in the crowd,

and a very great number of tents were set up in the country, on all sides, like a great encampment.

The gifts received by the sanctuary of Rocamadour were of great magnificence. Among them appears the forest of Mont-Salvy, given in 1119 by Odo,

Count of La Marche, to the Blessed Mary of Roc-Amandour.

The lands of Gornellas and Orbanella, for the good of the souls of his relatives,

by Alphonso IX, King of Leon, in 1181.

In the year 1202, Sancho VII, King of Navarre, gave a revenue of 48 pieces of gold for lighting the chapel of Notre Dame. In 1208, Savaric,

Prince of Mauleon, a great captain and famous troubadour, gave as a pure and perpetual alms, to the Blessed Mary of Rocamadour, his land of Lisleau,

with absolute exemption from all tax and charge. Pope Clement V, in 1314, left a legacy to the same church, to keep up perpetually a lighted wax candle

honorably in a vase or dish of silver, in the chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Rocamadour, to honor this Blessed Virgin, and obtain the deliverance of his soul.

It would be too long to cite the other benefactors of the chapel of Mary; the whole extent of this blessed rock shone with votive offerings of gold,

pearls, and precious stones. Spanish princesses had worked its rich hangings with their own hands, and fourteen lamps of massive silver, the twisted chains of

which formed a magnificent network, lighted up Our Lady of Rocamadour night and day.

It would be too long to cite the other benefactors of the chapel of Mary; the whole extent of this blessed rock shone with votive offerings of gold,

pearls, and precious stones. Spanish princesses had worked its rich hangings with their own hands, and fourteen lamps of massive silver, the twisted chains of

which formed a magnificent network, lighted up Our Lady of Rocamadour night and day.

By a contrast not found anywhere but in Christendom, the altar of the Madonna was of wood, as it probably was in the time of Saint Amadour.

A remarkable object in the roof of the chapel, in a belfry, surrounded by brilliant windows of painted glass, was a small bell without any rope,

which sounded by itself whenever it pleased the Star of the Sea to manifest Her power in favor of vessels in distress which called upon Her amidst the solitudes

of the ocean. Many stories recount how men at sea had implored the Black Madonna of Rocamadour to save them from a storm. They promised to undertake a pilgrimage

to Her sanctuary if She spared their lives. Months later, when they arrived to fulfill their promise and told their story, the priests would say something like,

Oh, so it was you for whom the bell tolled, letting us know that someone in distress at sea was being saved! We were expecting your arrival.

A stone plaque on the wall lists fifteen years between 1385 and 1617 when the miraculous bell rang without human intervention.

After the discovery of the relics of St. Amator, the miracles at Rocamadour became so numerous that the monks began to keep a chronicle. By 1172 there were 129 well-known miracles included in the Book of Miracles published by the monks. Here is one of those accounts:

Three pilgrims from Gosa were passing through the lonely wastelands near Saint-Guilhem, when they were led astray by thieves along remote and impassable tracks, over steep mountains and along valley floors. The robbers treated these innocent people injuriously and attempted to steal the property belonging to these poor of Christ. But the Advocate of all mankind, the powerful Lady of Rocamadour, the exceptional Star who lights up the world with Her radiance, came to the aid of Her servants as they called out to Her. As was proper, She seized hold of the servants of iniquity, these workers of wickedness, and took away their sight, which is a human being's most cherished asset. She also paralyzed their hands and rendered them immobile like statues, out of pity leaving them only with the use of their tongues so that they could ask for mercy and express heartfelt penitence. And so with suppliant cries the robbers fell at the pilgrims' knees and asked that they placate the Lady, who is gentle but had been offended by their misdeeds, with their prayers and merits. The pilgrims were moved by the plight of the afflicted men, and their hearts were touched. They got down on the ground to pray, raised their voices to Heaven, and asked the Lady of Mercy to take pity on the wretches. Then the unique Mother of Compassion, the people’s Hope for the forsaken who broke the neck of the dragon, the Restorer of health, restored the thieves' senses and returned their bodies to their former health.

Further sacrileges and devastation were visited upon the Shrine during the Reign of Terror in France. Rocamadour seemed to be but a shell of its former self. Nonetheless, pilgrims continued to climb those many stairs with the same sense of devotion and penance as did their ancestors. It has been admitted by the present-day keepers of the Shrine that the iconoclasm (destruction of images) perpetrated by the fanatics of the Vatican II era was worse than that of the Calvinists or the Freemasons of former times. Indeed pilgrims of our own times have much to offer reparation for.

Alphabetical Index; Calendar List of Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com