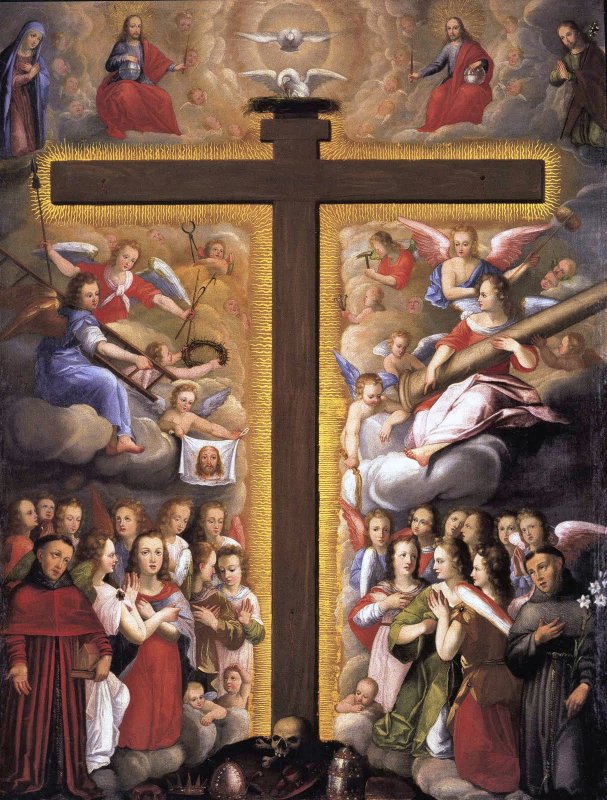

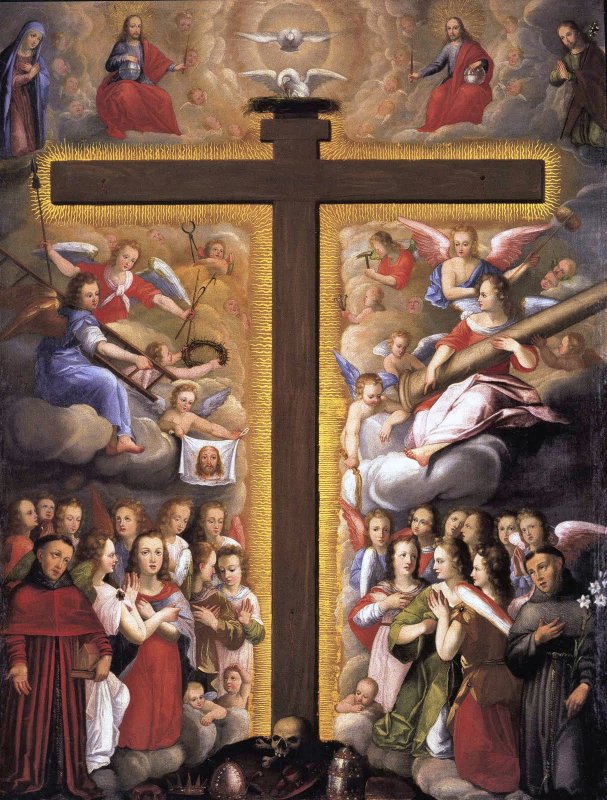

A. The plan of salvation is realized by the actual application of the fruits of the Redemption to individuals.

A. The plan of salvation is realized by the actual application of the fruits of the Redemption to individuals. A. The plan of salvation is realized by the actual application of the fruits of the Redemption to individuals.

A. The plan of salvation is realized by the actual application of the fruits of the Redemption to individuals.

Although Christ died for all, yet all do not reap the benefit of His death; but only those who make themselves partakers of the merits of His Passion (Council of Trent Sess. 6, can. 3). The Passion of Christ is a life-giving remedy; but as a medicine, though efficacious in itself, profits only those who actually use it, so also the saving remedy of Christ's Passion and Death. God, Who procured the means of salvation for one and all, requires our own cooperation. The merits and satisfactions of Jesus Christ, on the one hand, are communicated or applied to us by God; but, on the other hand, they must be applied or appropriated by ourselves.

I. The fruits of the Redemption – the merits and satisfactions of Jesus Christ – are not merely imputed to us externally; they must be internally communicated, and made our own.

(a) Christ by the Redemption became our new spiritual Head (Rom. 5: 18), as Adam was our natural head and was destined to become our spiritual head. But Adam was our natural head by the fact that the natural goods conferred on him were to become the possession of his children individually; and he was likewise to become our spiritual father by actually transmitting original justice, with all its accompanying gifts, to his children individually. Therefore Christ, also, as our spiritual Head, was to confer those blessings on us individually, as something belonging to us personally.

(b) By His death on the Cross, Christ not only made satisfaction to God's justice and atoned for our sins, but also restored to us sanctifying grace and the inheritance of the children of God. But these spiritual gifts were an inherent quality of the soul, which rendered it the supernatural image of God. Therefore, the fruits of Christ's death on the Cross must likewise be real spiritual gifts, inherent in the soul, and raising it to a supernatural state; but this can be the case only in the supposition that these gifts are really communicated to us as our own.

By the communication of the fruits of Christ's Passion a renewal and regeneration of man takes place. Unless a man be

born again of water and the Holy Ghost, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God

(John 3: 5). This regeneration is attributed

to the Holy Ghost; for the communication of gifts and graces is the peculiar function of the Third Person of the Holy Trinity, Who proceeds

through the will or mutual love of the other Two Persons, and is, therefore, the Divine Love and the bond between the Father and the Son.

II. Although the beginning and finishing of our justification is from God, yet in the case of adults cooperation is necessary. By our own actions, inspired and executed by divine grace, we must appropriate to ourselves the merits of Christ Crucified.

(a) To this cooperation God exhorts us with the words: Turn ye to Me, and I will turn to you

(Zach. 1: 3).

Again, by the words: Convert us, O Lord, to Thee, and we shall be converted

(Lament. 5: 21), we are reminded of our own inability and

the efficacy of God's assistance. Our participation in the merits of Christ is, therefore, the effect at the same time of divine and human action

(Council of Trent, Sess. 6, can. 5).

(b) Holy Scripture in numerous passages points to the necessity of our own cooperation in order to reap the fruits of the Redemption. Now it urges the necessity of faith, now the use of the means of grace instituted by Christ, now the observance of the Commandments. Hence the charge given by Christ to His Apostles to teach all nations, baptizing them, and teaching them to observe all things whatsoever He had commanded (Matt. 23: 19-20).

(c) For the rest, it is but meet that man, endowed as he is with free will, should by its use attain to his end,

that is, to the full possession of the fruits of the Redemption. Therefore St. Augustine (Serm. 169 [ed. Maur.] c. 11, n. 13) says:

He Who created thee without thy doing does not justify thee without thy doing. He made thee without thy knowledge, but He will justify

thee only by thy own will.

B. Christ raised Christian marriage to the dignity of a Sacrament.

Protestants denied the sacramental character of Matrimony – but unjustly, since Christ gave it all the marks of a Sacrament.

I. He made it an outward sign of inward grace; in the first place by making it a representation of His own union with

the Church. St. Paul says: A husband is head of the wife, just as Christ is head of the Church, being Himself Savior of the body.

But just as the Church is subject to Christ, so also let wives be to their husbands in all things. Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ

also loved the Church, and delivered Himself up for Her

(Eph. 5: 22-29). Now, Matrimony could not represent the union of Christ

with the Church, and on this very ground impose special obligations on man and wife, unless it also conferred grace upon them to fulfill

these obligations. Since, therefore, Christ not only restored marriage to its original perfection, but also made it a figure of His union

with the Church, it is, like the other Sacraments, a sign instituted by God, and productive of grace. Therefore St. Paul calls it a great

Sacrament, or mystery, in Christ and in the Church

(Eph. 5: 32).

II. The Church always regarded Matrimony as a sacred sign productive of grace – as a Sacrament. St. Augustine †430

(de nupt. et concup. I c. 10) puts it on the same line with Baptism and Holy Orders. In like manner, Popes Innocent I and Leo I.

The Eastern sects also agree with the Catholic Church on this point. Finally, the Council of Trent (Sess. 24, c. 1) declares:

If anyone assert that Matrimony is not really and truly one of the seven Sacraments of the evangelical law, instituted by Christ,

but that it is of human invention; let him be anathema.

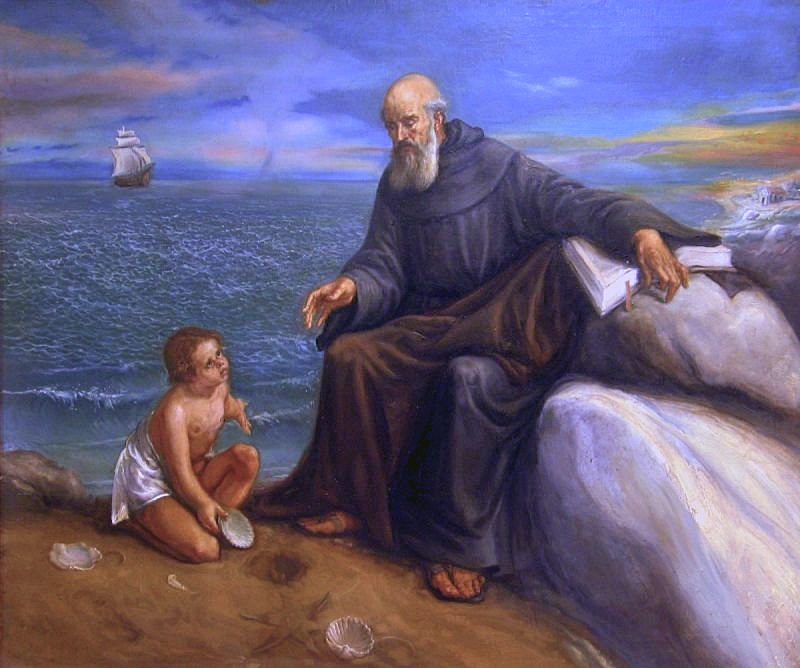

St. Augustine is said to have seen a young boy trying to empty the water of the sea into a small hole.

When he told the boy that he could not

fit that much water into the hole, the boy replied that neither could the Saint fit the Mystery of the Holy Trinity into his own mind.

Man can never fully understand Mysteries such as grace and free will.

B. Grace is a supernatural aid or gift, and may be either actual or habitual.

I. By grace, in the strict sense of the word, is understood a spiritual, supernatural aid or gift granted to us by God through the merits of Christ for our eternal salvation.

Grace (gratia), in the widest sense, means either God's benevolence (Luke 1: 30) or any gift freely bestowed by God. The gifts bestowed upon us by God's pure bounty are either natural or supernatural. By natural gifts we mean those that are given us with human nature itself, or which result from our own natural activity, or which are in some way due to nature. Supernatural, on the other hand, are those gifts which neither form part of human nature, nor result from it, nor are in any way due to it. Such is particularly our future happiness, consisting as it does in the contemplation of God face to face, and all that actually disposes and enables us to attain to that end. Such supernatural gifts are either external or internal. The Gospel, the miracles and the example of Christ are external graces. The divine influence which moves our souls, preparing them for the attainment of supernatural happiness – the supernatural enlightenment of the mind and inspiration of the will, with all the other gifts bestowed on us by God for our supernatural end – are internal graces. These internal helps or gifts are graces in a stricter sense of the word. Internal gifts may be conferred on man either for his own salvation or for that of others. Thus the inspiration of the will to do good and avoid evil is given for our salvation; the gift of miracles, prophecy, etc., is conferred for the benefit of others. The former kind is called gratia gratis faciens, because it renders the possessor pleasing to God; the latter is called gratia gratis data – gratuitously given. Only those graces which make us pleasing to God are called graces in the strictest sense. In our present fallen state, grace is given to us in view of the merits of Christ, since by His death He has reconciled us with God, and purchased for us the means of salvation.

II. Grace thus taken in its strictest sense is divided into actual or transient grace (also called helping grace) and habitual or sanctifying grace (also called the grace of justification).

(a) Actual grace consists in the supernatural enlightenment of the understanding and inspiration of the will, to shun what is evil, and to will and do what is good. It is called actual because it is not permanent or inherent, but a transient divine influence upon the soul.

Actual grace is called preventing (praeveniens), helping (adjuvans), or consequent (perficiens), according as it arouses or solicits our natural faculties to do good or avoid evil, or aids the will in its free resolve, or, finally, strengthens it in the execution of its good purpose.

(b) Habitual or sanctifying grace is an inward gift communicated by God to the soul, in virtue of which man is made holy and pleasing to God, a child of God, and an heir of Heaven.

Sanctifying grace, being an abiding quality, is called a gift (donum) in the strict sense of the word. This applies for similar reasons to all supernatural qualities or habits. Actual grace, on the other hand, consisting in a transient act, not in a permanent quality, is called a help (auxilium).

C. Grace is necessary to everything that is profitable for our eternal salvation.

Pelagius and his followers in the fifth century denied not only the state of original justice and the existence of original sin, but also of the necessity of grace. They asserted, at first, that man's natural strength was sufficient to enable him to observe all the commandments of God, to overcome temptations, and to gain everlasting life. At a later stage of the controversy, they accepted the word grace, but only in the meaning of free will. Still further pressed, they substituted for free will the teaching of the Gospel and the example of Christ, which are supernatural, indeed, but only external graces. Finally, they admitted the necessity of the enlightenment of the mind, but not of the inspiration or strengthening of the will, still maintaining that this enlightenment, which, for the rest, could be obtained by natural good works, was not necessary to enable a man simply to do good, but only to enable him to do it more easily. The Catholic Church, on the other hand, teaches that a supernatural and inward grace, influencing both the understanding and the will, is absolutely necessary for the performance of all works profitable for salvation. We call profitable for salvation, or salutary, anything in any way conducing to salvation, though it be not in itself meritorious of eternal life, like good works performed in the state of sanctifying grace.

I. According to the teaching of Holy Scripture, we are not of ourselves capable of thinking, willing, or accomplishing

anything profitable for salvation, but only by a divine and supernatural influence. St. Paul declares that we are not sufficient to think anything

of ourselves, as of ourselves; but our sufficiency is from God

(2 Cor. 3: 5). Again: It is God Who worketh in you both to will

and to accomplish, according to His good will

(Phil. 2: 13). Without Me you can do nothing

(John 15: 5).

In these passages is asserted, not only a great difficulty, but the utter impossibility of our doing anything of ourselves that is profitable for

salvation (cf. Eph. 2: 10; John 6: 14; 15: 4-5).

II. The Church's conviction of the necessity of grace is manifest from the stealthy manner in which Pelagius sought to introduce his heresy – his efforts to deceive the pastors of the Church by ambiguous words and the perversion of the meaning of orthodox expressions; by the firmness with which the Fathers; especially St. Jerome and St. Augustine, opposed his doctrine; and, finally, by the Church's explicit definitions against Pelagianism (Council of Trent, Sess. 6, can. 2, 3).

III. The necessity of grace for all that is conducive to salvation follows from the very nature of eternal salvation. Our eternal salvation is supernatural, i.e., of a higher order. Consequently, the means by which we are to attain to it must be supernatural, and belong to the same order, for the means must be proportionate to the end. We can no more attain to eternal life by purely natural means than we can hear with our eyes or see with our ears or understand with our external senses.

An external and accidental cause of the necessity of grace is the weakness of our natural powers resulting from original sin. Even in the state of pure nature we should require at least a special natural aid to overcome the difficulties of observing the natural law. Much more do we need a special assistance in our present state, as the difficulties connected with the supernatural order are still greater. But in the present order this aid must be a supernatural one, because it is a means to a supernatural end. As in our fallen state this supernatural grace heals our languid nature from the wounds of original sin, it is called in contradistinction to original justice remedial grace (gratia medicinalis).

D. Grace is also necessary for the good will to believe, and for the first desire of salvation.

In the course of the Pelagian controversy there arose in southern Gaul a numerous sect which, unlike the Pelagians, admitted the state of original justice as well as the fallen state, and the necessity of grace for salutary works, but maintained that the beginning of salvation is the result, not of grace, but of free will; that man, in virtue of his own free will, arouses within himself the good will to believe and the first desire of salvation, and thus infallibly obtains the first preventing (preceding) grace. Thus the will prevents grace, and grace the will. The followers of this doctrine were known as Semi-Pelagians, because they adopted only part of the Pelagian heresy. The Catholic Church, on the other hand, teaches that grace is not only necessary for faith, but also for the good will, or readiness, to believe, and for the first desire of salvation.

I. According to the teaching of St. Paul (2 Cor. 3: 5; see images above and below), we are not of ourselves sufficient even to have a

salutary thought – a thought that is in any way profitable for our salvation. But a thought is less than a good will or desire; for it is less closely

connected with the work of our salvation. If, therefore, a thought, which only precedes and leads the way to faith, must come from God, how much more the will

or desire to be saved. If the beginning of salvation came from ourselves, so that God had to await our good pleasure in order to confer His grace upon us,

St. Paul could not say: Who hath first given to Him [God], and recompense shall be made to him?

(Rom. 11: 35). Grace would no longer be

gratuitous, and would not be purely the work of God's goodness; it would cease to be grace, that is, a free gift of God. If the beginning of salvation

were the work of man's free will and not of preventing grace, the Apostle could not say: Who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not

received?

(1 Cor. 4: 7). Predestination to grace and salvation in that case would not be the work of God, but of man.

II. Semi-Pelagianism and Pelagianism were rejected as heresies by the Fathers, especially by St. Augustine. The decrees formulated against them by the Second Council of Orange, 529 A.D. (cf. can. 5), after being confirmed by Pope Boniface II, were accepted by the whole Church.

III. The desire of salvation and the readiness to believe, which lead to faith and conversion, are the first steps towards justification, the foundation of the supernatural structure, and, therefore, a means towards the attainment of eternal salvation. But such they can be only in the supposition that they are supernatural acts; for the means must be proportioned to the end; nor can they be supernatural without grace.

We can, therefore, neither merit nor in any way obtain grace by our own natural resources. The first grace is always unmerited,

and is altogether a free gift of God's goodness; for if by grace, it is not now by works; otherwise grace is no more grace

(Rom. 11: 6). Neither can we by merely natural works positively dispose ourselves, i.e., make ourselves worthy of the first grace;

for there is no proportion between what is natural and what is supernatural; nor does God await man's will, but He prevents (precedes) it by His grace.

Man can, however, negatively dispose himself, i.e., abstain from sin. For sin would make him not only less worthy, but also less susceptible to God's grace;

though no sin, however grievous, forms an absolute obstacle to grace. God gives sufficient grace to all, even to unbelievers.

Therefore the generally received principle, That God does not refuse His grace to those who do what lies in their power,

must be understood to mean,

that God does not refuse further graces to those who, to the best of their ability, cooperate with the graces given them.

E. The necessity of grace extends also to the observance of the natural moral order.

Pelagius, having denied the existence of original sin and its consequences, was forced to the conclusion that man in his present state, by his own natural power, is equally capable of knowing the natural truths of religion and morality, of observing the natural law, and of overcoming grievous temptations as our first parents were. We do not here speak of supernatural truths, or of an observance of the natural law or a victory over temptations which would be effectual for eternal salvation; for from what we have already said it follows that grace is absolutely necessary to that effect. We mean natural truths, an observance of the natural law and a victory over temptations based solely on natural motives. This necessity of grace results not from total depravity, but from moral weakness in man; therefore the necessity of grace for the observance of the natural law is not absolute, but only moral.

I. Man left to himself, without grace, without the aid of revelation or some equivalent, could not without error know the substance

of the truths of natural religion. (a) That man of his own nature, as at present constituted, is incapable of obtaining a sufficient knowledge

of the essential truths of religion has been shown to be the result of experience. How much less capable, then, is he of knowing the entire system

of religious truths without error? (b) We can more easily understand this incapacity, or invincible difficulty, from the darkness of man's

understanding resulting from original sin. (c) Hence Scripture says: The thoughts of mortal men are fearful, and our counsels uncertain.

For the corruptible body is a load upon the soul, and the earthly habitation presseth down the mind

(Wis. 9: 14-15).

Man can, however, by his own natural faculties, without the assistance of grace, arrive at the knowledge of the existence of God, and of some other religious truths. Nay, he cannot completely elude all knowledge of God and of the principles of morality.

II. Without the aid of grace it is impossible for man to observe the entire code of the natural law for any considerable

length of time. Man left to himself will, at some moment or other, transgress the moral law, because of the difficulties connected with its observance.

His transgression will be voluntary, and therefore sinful, because at that particular moment it was not impossible for him to observe the law,

and because God, moreover, was ready to supply by His assistance what was wanting to him. (a) What the Apostle says of himself applies to all men.

I see another law in my members fighting against the law of my mind, and captivating me in the law of sin, that is in my members.

Unhappy man that I am, who shall deliver me from the body of this death? The grace of God by Jesus Christ Our Lord

(Rom. 7: 23-25).

It is not in himself, therefore, but in God's grace that St. Paul possessed power to observe the law of the mind, the moral law.

(b) If, on the one hand, we consider the difficulty of observing the whole law, and on the other hand, the instability of man's will

resulting from original sin, we may easily perceive that man cannot of his own strength constantly fulfill all his moral duties, but that he will sooner

or later violate them in some point or other. (c) The Fathers characterize as an error irreconcilable with the Catholic Faith the assertion of

Pelagius that without grace man can fulfill the entire law (c.f. S. Aug. de haeres. c. 88).

As original sin has not altogether destroyed man's free will and effaced from his soul the natural likeness of God, he is not of himself,

without the assistance of grace, unfit to fulfill his natural duties, so long as they involve no great difficulty. Hence St. Paul says that even

the heathens do by nature those things that are of the law

(Rom. 2: 14). It is, therefore, false to assert with Baius that

all works performed by unbelievers are sinful, and the virtues of the philosophers are vices,

or that he who admits the existence of a

naturally good work, i.e., a work proceeding from merely natural faculties, is guilty of Pelagianism

(prop. dam. 25, 37).

III. Without the aid of grace man is unable from a morally good motive to overcome strong temptations. He may be able to resist the allurements of one passion by motives derived from another – for instance, lust by the motives of ambition or avarice – but without the assistance of grace motives founded on morality or a sense of duty are not sufficiently strong to secure him against violent temptations. For, (a) in consequence of original sin his intellect is too much obscured, especially in regard to suprasensible truths, and his will too weak efficaciously to struggle after that which is beyond the realm of sense. (b) Hence St. Paul (Rom. 7: 25) hoped from grace alone to obtain strength sufficient to overcome his evil inclinations. (c) The holy Fathers are wont to infer this necessity of grace from Christ's precept to watch and pray, that we may not enter into temptation (S. Aug. de bono vid. c. 17).

As man can of his own strength discharge the easier moral duties, so he can also of himself overcome the lesser temptations; for every difficulty which deters us from doing our duty is a temptation to evil, and therefore the possibility of fulfilling easier duties implies the possibility of overcoming lighter temptations.

F. The assistance of grace is necessary also for the just (1) to perform supernatural works, (2) to observe the moral law and overcome grievous temptations; while (3) final perseverance requires a special grace, and (4) the preservation from all venial sins is an extraordinary privilege.

I. The just man needs the help of grace for the performance of supernatural works, whether this aid is habitual, consisting in sanctifying grace itself with the accompanying virtues, or, what is more probable, actual grace, distinct from the grace of justification.

(a) As the branch cannot bear fruit of itself, unless it abide in the vine, so neither can you unless you abide in Me...

Without Me you can do nothing

(John 15: 4-5). These words were addressed to the disciples, who are presumed to possess the grace of

justification, and, consequently, they cannot refer to sanctifying grace; therefore actual grace is necessary also for the just.

(b) The Council of Trent (Sess. 6, can. 22) says that as the head infuses strength into the members, and the vine into

the branches, so Christ constantly infuses strength into the just, which always precedes, attends, and follows their good works, and without which they

in nowise could please God.

(c) Though the just man possesses in sanctifying grace the power to perform supernaturally good works, yet this power must be aroused and sustained; and this is done by means of actual grace.

II.The just, moreover, need actual grace to enable them to observe the entire moral law, and to overcome strong temptations. For the reasons advanced above (E) are of a general nature, and may be applied also in the case of the just man. He who is in the state of grace is still weak; for sanctifying grace does not remove the difficulties arising from our depraved nature.

III. Even the just man needs a special grace to persevere in good to the end.

Those are called ordinary graces which are given to all the just in virtue of sanctifying grace. The grace or series of graces constituting final perseverance is not necessarily connected with sanctifying grace, and is, consequently, itself an extraordinary grace.

(a) St. Paul attributes perseverance in good to the same cause as the beginning of salvation: He who hath begun a good work in you

will perfect it unto the day of Jesus Christ

(Phil. 1: 6). But the beginning is from God; therefore also the consummation.

(b) The Second Council of Orange (c. 10) teaches against the Semi-Pelagians, who attributed perseverance to man's free will,

that the regenerate and holy must also implore the help of God in order to be able to attain to a happy end or perseverance in good.

The Council of Trent (Sess. 6, can. 22) condemns the assertion that the just man can without a special assistance of God

(sine speciali auxilio) persevere in justice, or that with such assistance he is unable to persevere.

IV. The just require a very special privilege, exceptionally granted to very few, in order to avoid, not only mortal, but also venial sins during the whole or even a considerable part of life.

(a) In many things we all offend

(James 3: 2). Here the Apostle speaks generally, and addresses himself directly

to the early Christians, who are to be presumed in the state of grace.

(b) The Fathers and the Councils of the Church defend this doctrine as a Catholic truth against the Pelagians; and they expressly teach that, owing to the depravity of human nature, without God's special providence and protection man is unable to guard against all transgressions (cf. St. Aug. de civ. Dei, XIX, c. 27). True, if man sins he does so voluntarily; but certain it is that, owing to his weakness and to the difficulty of perfectly fulfilling all his duties, he will fall sooner or later.

(c) The Council of Trent (Sess. 6, can. 23), in accordance with Scripture and Tradition, condemns those who maintain that

the just man can, during his whole life, without a special divine privilege (speciali Dei privilegio), avoid all, even venial sins,

as the Church believes concerning the Blessed Virgin Mary.

G. God gives sufficient grace to all men – also to sinners and infidels.

I. God gives sufficient grace to all the just to fulfill their duties and to overcome temptations. (a) The eyes of the

Lord are upon the just, and His ears unto their prayers

(1 Peter 3: 12). This particular care of God for the just entitles us to conclude

that He will give them all the graces requisite for their salvation, at least if they ask for them. St. Paul, addressing the first Christians,

whom we may reasonably presume to be just, says: Wherefore he that thinketh himself to stand, let him take heed lest he fall... God is faithful,

Who will not suffer you to be tempted above that which you are able, but will make also with temptation issue, that you may be able to bear it

(1 Cor. 10: 11-13). God therefore, being faithful, gives to the just grace either immediately sufficient for the fulfillment of all

their duties and for the victory over all their temptations, or at least mediately sufficient – i.e., the grace of prayer, by means of which

they may obtain further graces. (b) The Council of Trent (Sess. 6, can. 18, cf. can. 14) condemns the heretics who asserted that

it is impossible even for the just and those living in the state of grace to keep all of God's commandments.

Pope Innocent X condemned as

heretical the proposition of Jansenius: Some of the commandments of God are impossible to observe for the just, considering their present powers,

despite all their good will and efforts; the grace by which they may be fulfilled is also wanting.

(c) It is inconceivable that God,

Who is full of goodness towards all, would refuse the just, who are His friends and children, the means necessary for observing His commandments

and eternal salvation.

II. God gives also to those who are in the state of sin sufficient grace to keep the commandments, consequently to avoid

further sin, and to be converted to God. (a) The sinner, as we must conclude from the many warnings addressed to him in Scripture,

is bound to keep the commandments, and to avoid sin. But such an obligation cannot exist without the grace sufficient for its fulfillment,

since man's natural strength is insufficient. The repeated exhortations to penance, moreover, suppose that conversion is possible;

but without grace it would be impossible. Therefore the Apostle says: The Lord dealeth patiently for your sake, not willing that any should perish,

but that all should return to penance

(2 Peter 3: 9). (b) Again, if God had not promised His grace to all without exception,

the Council of Trent (Sess. 6, can. 14) could not teach without restriction that those who have lost the grace of justification once

acquired may again be justified.

Therefore God never so abandons the sinner as to withdraw His grace entirely from him.

Though God has promised the supernatural means of conversion to all sinners, yet He has not assured them of the continuance of those natural conditions without which grace cannot be effectual. Thus He has not promised them the free use of their mental faculties to the end of their lives.

III. God gives even to infidels sufficient grace to enable them to believe and to save their souls. (a) The refusal to accept the teaching of the Gospel, contrary to the words of Christ (John 16: 18-19), would be no sin if those to whom it was preached did not receive grace sufficient to believe. (b) Faith is no less necessary for salvation than the keeping of the commandments; therefore it must be equally possible. But it is not possible without sufficient grace to believe. We have, in fact, the testimony of Scripture (Wis. 12) that the heathen tribes of Canaan particularly experienced the influence of grace. Hence the doctrine that pagans, Jews, heretics, and the like, receive no influence from Jesus Christ has been condemned by Pope Alexander VIII.

The heathen, who is in total ignorance of revelation, but spurns the inspirations of God, sins, of course, by resisting God's grace. However, the first solicitations of grace are not a revelation, nor the light of Faith; they are only a supernatural inspiration, whereby God would dispose the soul of the unbeliever, and bring it to the Faith.

H. Grace can be rendered inefficacious by man's free will.

Jansenius, a native of Laerdam, in Holland (born 1535) taught that in our present state internal grace can never be resisted; that, consequently, every grace is efficacious, i.e., attains its end; and that a grace which is merely sufficient – with which one can cooperate, but does not – is never given. According to Jansenius grace is a pure spiritual delectation, opposed to impure earthly concupiscence of the heart. Grace and concupiscence are to each other as the two scales of a balance. If the spiritual appetite is stronger, it outweighs the earthly, and man follows it; if the sensual appetite is stronger, it conquers the spiritual, and man's will follows concupiscence. In short, if grace preponderates so that man can cooperate with it, he will actually cooperate; if, on the other hand, he follows his sensual appetite, it is because grace weighs so little in the balance that his will cannot cooperate. This doctrine was justly declared heretical by the Holy See.

I. That man may resist grace and withhold his cooperation; that there is, consequently, grace which is barely sufficient,

but inefficacious through our own fault, may be concluded from the words of Our Lord: Jerusalem... thou that killest the prophets and stonest them

that are sent unto thee, how often would I have gathered together thy children as the hen doth gather her chickens under her wings, and

thou wouldst not

(Matt. 23:37). The judgments of God were executed on Jerusalem because it spurned the grace offered it

(cf. Matt. 11: 21 ; Acts 7:51).

II. If, as we have seen, sufficient grace is given, at least to all the just, to keep the commandments and to overcome temptations; and if, on the other hand, even the just yield to temptation and relapse into sin – it is manifest that there are graces which are sufficient, yet ineffectual through man's own fault.

III. St. Augustine, from whom Jansenius pretended to have taken his doctrine, is in perfect harmony with the Church, for he teaches that it depends upon man's free will to consent to the solicitation of grace, or to withhold his consent and render it ineffectual (de spir. et lit. c. 34).

I. The efficacy of grace does not impair the freedom of the will.

As grace consists in the enlightenment of the understanding and the inspiration of the will, every grace is efficacious in the sense

that it is productive of some activity. The first motions of grace, however, are involuntary, and not in man's power. Not until he is conscious

of them can he by the action of his free will cooperate with them or resist them. We call those graces strictly efficacious with which man

freely cooperates, which have the effect intended by God. That there are efficacious graces, which obtain their end, is as certain as it is that

there are supernaturally good actions; for every supernatural act is the effect of an efficacious grace. It is God Who worketh in you

both to will and to accomplish

(Phil. 2: 13). The so-called reformers

of the sixteenth century denied the freedom

of the human will under the influence of grace; and in this error the Jansenists substantially concurred. The freedom of the human will, however,

under the influence of grace is manifest both from Scripture and Tradition.

I. Scripture thus characterizes the just man: He that could have transgressed, and hath not transgressed,

and could do evil things, and hath not done them

(Ecclus. 31: 10). He who from a supernatural love of virtue abstains

from sin follows the inspiration of grace. But he follows the inspiration of grace voluntarily, since he could do the contrary.

And if it were not fully in our power to do good and shun evil, why should Scripture repeatedly exhort us to do so?

II. St. Augustine, to whom the adversaries of the Catholic doctrine on the efficacy of grace generally appealed, always maintained the freedom of the human will, and defended it ex professo in one of his works (de gratia et lib. arbit.) The Council of Trent (Sess. 6, can. 4) defined the Catholic doctrine against the innovators of the 16th century.

That God could direct man's will as He pleases without impairing its freedom, though we may not understand how, is manifest. For, being the almighty and absolute ruler of the universe, He can direct every creature according to its nature; consequently the will of man in accordance with its freedom. God's wisdom and power would not be infinite if man's malice could frustrate all His graces under all circumstances, and thus thwart His intent. Hence St. Augustine (ad Simplic. I. q. 6, n. 57), explaining this difficulty, appeals to God's omniscience, which foresees with what graces and under what circumstances man's free will would cooperate, so that He can give that grace with which He foresees that man would freely cooperate.

Alphabetical Index; Calendar List of Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com