A. The primitive revelation was supernatural in form and substance.

A. The primitive revelation was supernatural in form and substance. A. The primitive revelation was supernatural in form and substance.

A. The primitive revelation was supernatural in form and substance.

I. Our first parents received a revelation supernatural in form and substance; supernatural religion, therefore, reaches as far back as the creation of man.

Supernatural in substance is that revelation which communicates truths inaccessible to human reason, imposes obligations, holds out rewards and punishments depending solely upon God's free choice, or extending beyond the teachings of reason. Such were the truths, commandments, rewards, punishments contained in the religion communicated to our first parents. But if the primitive revelation was supernatural in substance, it was likewise in form; for supernatural truths can only be made known in a supernatural manner. Besides, the Sacred Writings expressly record that God conversed supernaturally with our first parents and made His will known to them by a positive revelation.

(a) Truths regarding his origin and condition were communicated to our first father which he could have learned only from revelation.

Even though he had known by the light of reason that God was his Creator, yet reason could not tell him that God had directly created his body as well as his soul;

nor could reason teach him how his body had been formed by God. But from the words: Till thou return to the earth, out of which thou was taken; for dust thou art,

and into dust thou shalt return

(Gen. 3: 19), we see that Adam was informed of both these facts. The same applies to the creation of Eve,

as may be seen from the words: This is bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh

(Gen. 2: 23). Moreover, the supernatural gift of the immortality of

his body was made known to Adam by revelation; for the threat of losing it by disobedience clearly implies its possession.

(b) A positive command is involved in the words: Of every tree of paradise thou shalt eat; but of the tree of knowledge of good and evil

thou shalt not eat.

(Gen. 2: 16-17).

II. After the fall the former supernatural state of friendship with God is restored; the conqueror of mankind himself is conquered;

and thus is again opened to man the prospect of future supernatural happiness. All this is contained in the solemn promise of a Redeemer.

I will put enmities between thee and the woman, and thy seed and her seed: she shall crush thy head, and thou shalt lie in wait for her heel

(Gen. 3: 15).

This promise, justly called the Protoevangel (first gospel), henceforth forms the germ of supernatural religion.

B. God exercised a special providence towards the preservation of the supernatural religion.

I. Though it was easy in the beginning, owing to the length of human life, to transmit to posterity the supernatural revelation once given, God nevertheless, to insure its preservation, continued His supernatural intercourse with the human race. With threats and punishments He rebuked the wayward Cain (Gen. 4); and subsequently, when moral corruption prevailed, His admonitions were conveyed through Noe to all mankind. Then followed the deluge – that great catastrophe which impressed itself indelibly upon the memory of mankind, and became to succeeding generations a striking evidence of God's retributive justice.

II. After the deluge God kept up an intimate conversation with Noe, the head of our rescued race. As to our first parents, so also to this new race

He gave a positive law:

II. After the deluge God kept up an intimate conversation with Noe, the head of our rescued race. As to our first parents, so also to this new race

He gave a positive law: Flesh with blood you shall not eat

(Gen. 9: 4). He made a new covenant with man, and chose the rainbow as its everlasting memorial.

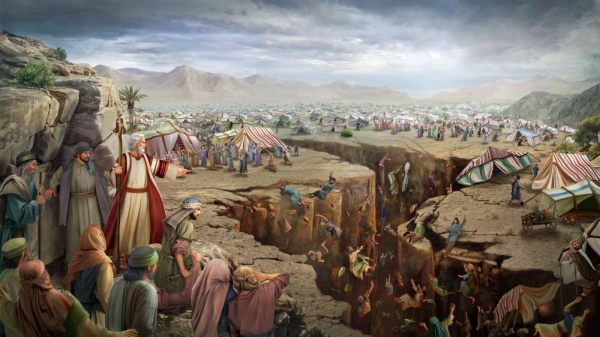

Through Noe God pronounced a blessing upon Sem and Japheth, and cursed Canaan, the son of Cham (image right).

The period from Adam to Abraham is called that of the natural law, because positive laws and supernatural revelations were not numerous during that time, and because there was as yet no proper code of laws, such as was afterwards given to God's people. At no time, however, was man exclusively under the natural law.

III. But the promise of a Redeemer made to Adam and Eve was renewed and more definitely expressed in the blessing pro-nounced by Noe on his sons, Sem and Japheth.

Blessed be the Lord God of Sem, be Canaan his servant. May God enlarge Japheth and may he dwell in the tents of Sem, and Canaan be his servant

(Gen. 9: 26-27).

Sem is especially blessed by the fact that he is chosen to be the ancestor of the Messias. Japheth is blessed, inasmuch as his descendants, who were scattered chiefly over Europe,

have reaped the blessings given to Sem. Here there is evidently a question of spiritual blessings, of spiritual goods, and of a spiritual dwelling in the tents of Sem;

for, if the descendants of Japheth had taken actual possession of the tents of Sem, or had seized on his material goods, the blessing of Japheth,

contrary to the intention of the giver, would have been a curse to Sem.

C. Yet a universal apostasy from natural as well as supernatural religion ensued under the form of paganism and idol-worship.

I. Notwithstanding the chastisement inflicted by the deluge, man soon returned to his evil ways. Once more God revealed Himself, as it were, visibly, when, by the confusion of tongues, He prevented the completion of the tower of Babel, which was the god of man's ambition and was intended to be the proud monument of his power. Yet corruption continued to increase. A second and almost universal apostasy from God ensued. Man disregarded the revealed truth and all God's commands and threats.

II. Then, as the Apostle says: God suffered all nations to walk in their own ways

(Acts 14: 15). From this time He does not, as a rule,

employ any extraordinary measures for their rescue, but leaves them partly to their religious traditions, until these became entirely disfigured; and partly to that

voice which, through God's creatures and human reason, speaks to every individual, proclaiming that there is a Lord of Heaven and earth, a supreme Law-Giver and Judge,

a Searcher of hearts. Thus God, even after men had rejected the gift of revelation, did not leave Himself without a witness

(Acts 14: 16). If there were

individuals among the heathens (by this name we distinguish those nations who did not possess the clear light of revelation) who knew and worshiped God as the Author of nature,

we may suppose that in His goodness He contrived a means to manifest Himself to them also as the Author of grace, and thus to bring them to salvation.

III. This natural testimony concerning God, however, though it could not be disregarded, was misinterpreted, and thus, to some extent, rendered ineffectual. In the place of the one true God other divinities were substituted by transferring to visible objects the original, true, though indefinite, idea of God as the sovereign Lord of all things, which is naturally developed in every man by the contemplation of the universe. Such was the origin of idolatry. The sensual nature of man, which leans towards sensible objects; servility towards the mighty of this earth; immoderate attachment to deceased friends and relatives, whose memory was perpetuated by images; finally, the evil one, who tried to rob God of the worship due to Him – such have been the immediate causes of ascribing divine attributes to natural objects, to heroes, to images, and even to demons. Thus arose various forms of idolatry.

D. By the call of Abraham and the separation of his posterity God secured the true religion among the Jewish people and thus prepared for the advent of the Redeemer.

While the nations were departing more and more from their Creator and going each its own way, God chose Abraham, a descendant of Sem,

and made him the father of a race which was to be the special object of His solicitude, the guardian of the supernatural revelation, and the herald of the promised Messias.

This race, from which the Messias was to spring, was, by its separation from other nations, and by extraordinary temporal blessings, privileged and sanctified above the rest

of mankind, and, at the same time, preserved from moral corruption. God, if He chose, could have effected this design by other supernatural means;

but, in His wisdom, He loves to give a natural groundwork to His supernatural dispensations. Abraham was ordered to leave Chaldea, his own country, and to go into Canaan.

God spoke to him: I will make of thee a great people, and bless thee

(Gen. 12: 2-3). Henceforth God continued to converse familiarly with Abraham.

As a sign of His covenant with him He chose circumcision; and herein is the first vestige of the Mosaic law.

But God gave also special and, at times, appalling evidences of a supernatural providence towards other peoples. Thus, for instance, Sodom and Gomorrha were destroyed by fire and brimstone in punishment for their unnatural crimes.

E. At the separation of the Jewish people God intended the reunion of the human race through the coming Redeemer.

The human race was not, however, to be divided by an everlasting barrier. This separation was made rather in order that the Gentiles might, by their errors,

finally recognize the vanity of human aspirations, and thus become the more susceptible for salvation; and that the Jews, on the other hand, under the special guidance of God,

might be better fitted to communicate salvation to the Gentiles. Salvation was to proceed from the Messias, to whose coming henceforth God's people eagerly looked forward.

To the blessing pronounced on Abraham God added the promise: And in thee shall all the kindreds of the earth be blessed

(Gen. 12: 3).

This promise was still more explicitly repeated in favor of Abraham's son Isaac: In him all the nations of the earth shall be blessed

(Gen. 22: 18).

It cannot here be a question of temporal blessings; for such blessings have not been given to the nations through Abraham's posterity. According to Jewish and Christian tradition,

these words refer to the spiritual blessings already promised to our first parents, which the Messias was to bring (Gal. 3: 8, 16). Jacob, the last of the patriarchs,

at his death, addressed to his son Juda, and through him to the tribe called after his name, the following words: The scepter shall not be taken away from Juda,

nor a ruler from his thigh, till He come that is to be sent, and He shall be the expectation of nations”

(Gen. 49: 10). The time of the coming of the Messias

was to be marked by the cessation of the sovereignty of the Jewish nation. At the coming of the Desired of nations, the barrier between the Gentiles and the chosen people

was to be removed.

F. The Mosaic law, as to its contents, was partly of a general nature, regarding all mankind; partly of a special character, regarding only the people of Israel.

The revelation made to the people of God through Moses is called the Law, because of the many precepts and ordinances which it contained. Its contents are partly of a general and partly of a special nature.

I. We call that part of the Mosaic law general which reveals truths or contains commandments directed to, and binding on, all mankind. Among them are chiefly those truths which make up the substance of the primitive revelation – the doctrine concerning God as our Creator and last end, and regarding the promised Redeemer. The Mosaic revelation gave great prominence to the unity of God, because this doctrine, though clearly contained in the patriarchal revelation, had been gradually lost sight of by other nations. The immortality of the soul, on the other hand, was barely hinted at, or taken for granted rather than emphasized. The natural moral law was definitely proposed in the Decalogue, which contained the immediate references from the universal moral law, and which, being based upon the natural relations of man to God, is equally binding upon all.

II. The special part of the Mosaic law consists of those ordinances which concerned only the people of Israel.

1. Among the latter are many of the more remote applications of the natural moral law, whereby certain actions are, under given circumstances, commanded, forbidden, advised, or permitted. If some things which are permitted or tolerated are not quite consistent with the perfection of the moral law, the reason is to be found in peculiar circumstances. This applies especially to polygamy. For although it is inconsistent with the perfection of marriage, yet the Israelites as formerly to the patriarchs, because the chosen people were to be multiplied, not, like the Christians, by way of aggregation (conversion), but by natural propagation. Divorce, which is likewise not in accordance with the perfection of the marriage bond, could have been permitted or tolerated to prevent greater evils (e.g., domestic strife and murder.)

2. The ceremonial law, which defined the manner of divine worship, was founded, it is true, upon a principle binding upon all men. But the special ordinances, which depended solely upon God's free choice, concerned the people of Israel only. Among them are: (a) Sacred ordinances, such as abstinence, ablutions, circumcision, the various kinds of sacrifices, etc. (b) Sacred places, vessels, etc., e.g., the temple, the tabernacle. (c) Holy seasons, viz., numerous feasts, chiefly in commemoration of divine favors. (d) Sacred persons, viz. priests and levites, with the high priest, the supreme judge in religious matters, at their head. The Prophets, who arose from time to time, were extraordinary messengers of God, whose mission it was to direct the people's attention to the coming Messias, to unfold the doctrines of faith, and to inculcate the observance of the law.

The multitude of precepts and observances was calculated to separate the chosen people from other nations, and to perpetuate the remembrance of

the true God and of His promises. Besides, the ceremonial law had also the remoter object of foreshadowing things to come

(Col. 2: 16; Heb. 10: 1),

as prefiguring Christ and the spiritual goods to be obtained through Him. The Old Testament was, in the words of St. Augustine (de Civ. Dei, xvi, 26),

the veil of the New, and the New Testament the unveiling of the Old.

Thus, the paschal lamb is not only a ceremonial of the deliverance from Egypt,

but a type of the Sacrifice of Christ on the Cross and of our deliverance from the bondage of sin.

3. The civil law regulates the mutual relations of superiors and subjects; of subjects among themselves; of the members of families to one another; and, finally, the relation of God's people to foreigners. God was properly King of the people of Israel in virtue of the covenant made with them (Exod. 19: 4-8; Deut. 26: 16-19). As such He was acknowledged by the people, and as such He manifested Himself to them (Num. 27: 21). Although this relation had been somewhat changed by the subsequent institution of kings, yet God did not thereby cease to be the King of Israel, since the visible kings were regarded only as His representatives. By means of this theocracy the people were more effectually preserved from idolatry, while all their observances, even those of the civil law, were marked by a sacred character.

G. The Mosaic law had also a twofold sanction; one temporal, or pertaining to this life; and one spiritual, or pertaining to the next.

G. The Mosaic law had also a twofold sanction; one temporal, or pertaining to this life; and one spiritual, or pertaining to the next.

As the substance of the Mosaic law was of a twofold character, so also its sanction, that is, the reward or punishment destined for those who obeyed or transgressed it.

I. Moses in the law points explicitly only to temporal prosperity as the reward for the observance of the law, and to temporal evils as the punishment for its transgression. In this sense we may say that the Mosaic law had only a temporal sanction, and, in fact, the people's attention was justly directed to this kind of sanction. For, being prompt of execution, such sanction was especially fitted to incite them to the observance of the law, and was in keeping with God's relation to them as temporal Sovereign.

II. A future spiritual recompense, however, was also held out to the observers of the law. The Israelites could not have been ignorant that some sort of reward for good and punishment for evil was to be expected in the next life, since even the pagans, particularly the Egyptians, believed in the immortality of the soul, as well as in some sort of future retribution. But the Israelites knew that reward to be a supernatural one; for such was the promise made to the patriarchs (Heb. 9 and 11), consequently also to the Israelites, on whom the natural moral law and other traditional precepts were likewise binding. It was also the general conviction of the Jews at the time of Christ that by observing the law they would possess everlasting life (Luke 18: 18). This future reward was promised not only for obedience to the moral law, but even for the observance of positive ordinances, though the Mosaic law makes no express mention of it – for these ordinances were likewise given by God's command, and were, therefore, suited to be the object of a future recompense.

Though it was possible for those who lived under the pre-Christian dispensation to obtain justification through sanctifying grace (Heb. 11), yet the Old Law, as such, could not confer it. It is true, the law prescribed those acts which lead to justification and to salvation – acts of faith, hope, and charity; but grace, which alone renders efficacious the exercise of these and similar acts, was not the property of the Old Covenant, but was peculiar to the Christian dispensation, in view of which it was conferred in the Old Law.

H. The Mosaic law was to be abolished by the Messias.

The Mosaic law, directly as well as indirectly, point to its own future abolition.

The Mosaic law, directly as well as indirectly, point to its own future abolition.

I. If the division of the human race effected by the call of Abraham was to cease on the coming of the Messias (see Section E); therefore the barrier raised by the Mosaic legislation was destined to be removed. Since the heathen world was not to be excluded from salvation; since, moreover, the Gentiles also, though less definitely, looked forward to a Redeemer, they too were to be incorporated with Him, to appropriate the blessings which He brought them; and thus He was destined to unite both Jew and Gentile in one religious communion. This, however, could not be as long as the people of Israel were cut off from all the other nations, as long as Jerusalem was the only place where the true God was to be worshiped. The promise given to the patriarchs of a Messias – a Redeemer of all mankind – and, consequently, the founder of a new religion, which was to embrace all nations, contained an indirect allusion to the future abolition of the Mosaic law.

II. Still more definitely did the promise given by God on Mount Horeb point to a new Law-Giver and, consequently, to the abolition of the Mosaic law.

When the people, fearing the voice of the Lord and His majesty, begged Him to speak to them no more, the Lord said to Moses: I will raise them up a Prophet out of the

midst of their brethren like to thee; and I will put My words in His mouth, and He shall speak to them all I shall command him

(Deut. 18: 18). God promised a

Prophet like to Moses, and a Mediator between Him and His people. This Prophet was none other than He who in the New Law is so often called the Prophet, or the great Prophet,

who was to come into the world (John 6: 14). Thus St. Peter (Acts 3: 22) and St. Stephen (Acts 7: 37) interpret the Mosaic prophecy. And, in fact,

none other among the prophets who came after Moses, nor even the whole line of prophets collectively, could fully realize that promise; for there arose no more a

prophet in Israel like unto Moses

(Deut. 34: 10). Unless we admit that God's promise has remained unfulfilled, or that it was only very partially fulfilled,

we must conclude that it referred to a Prophet who was to be, like Moses, the Founder of a new law. For it is as a law-giver that Moses chiefly distinguished himself,

and here it is with reference to the Mosaic legislation that a Prophet like unto Moses, and, consequently, a Legislator, is promised. Thus the Mosaic law itself,

by pointing to the Messias as the Founder of a new law, expressly pronounces its own future abolition.

I. Moses proved his divine mission by miracles and prophecies.

If Moses was really a divine messenger, as he professed to be, the divine origin of what he taught as such is established by this very fact. But by the same fact the primitive and patriarchal revelations are also proved to be divine, because Moses, a messenger of God, based his law upon them as upon a supernatural foundation, and thus handed it down to posterity as divine. To convince ourselves of the divine mission of Moses we might appeal to his moral character, which excludes all possibility of imposture. We might point to the sublimity of his teaching concerning God at a time when other nations were shrouded in the darkness of ignorance and superstition. But the chief evidence of his divine mission are the miracles and prophecies on which he himself grounded his authority, as we have seen in the last article.

Two things must be established in regard to these miracles and prophecies in order that they may be considered as evidence of Moses' divine mission: (1) that they were real miracles and prophecies, and (2) that Moses appealed to them as evidence of his divine mission.

I. It cannot be denied that those extraordinary actions performed by Moses, and considered by him as miracles, were really such; and that his predictions were also true prophecies.

It is certain beyond doubt that in the narration of those facts, set down as miracles, we possess historical records, and not, as rationalists pretend,

mere poetical exaggerations of every-day occurrences. Moses characterizes them as supernatural facts when he thus addresses the people: Know this day the things

that your children know not, who saw not the chastisements of the Lord your God, His great doings and strong hand and stretched out arm, the signs and works which

He did in the midst of Egypt to king Pharao and to all his land, and to all the host of the Egyptians, and to their horses and chariots; how the waters of the Red Sea

covered them, when they pursued you, and how the Lord destroyed them until this present day: and what He hath done to you in the wilderness, till you came to this place:

and to Dathan and Abiron, whom the earth, opening her mouth, swallowed up with their households and tents. Your eyes have seen all the great works of the Lord,

that He hath done

(Deut. 6: 22). But how could the people permit every-day occurrences which they themselves had witnessed to be handed down to their

descendants as signs and wonders? There can be no doubt, then, that we possess an historical record in the Mosaic narrative.

1. The supernatural character of the facts related as miracles follows:

(a) Indirectly from the conduct of Moses and the Israelites and the behavior of their adversaries. If the facts characterized as miracles were

not really such, how could Moses have dared to make them the groundwork of his law? The assurance with which he appealed to them sufficiently proves that he was

fully convinced of their supernatural character. And how could he palm off mere natural phenomena as miracles on a people so suspicious and turbulent as the Jews

are known to have been? The people, in fact, had reason carefully to inquire into the circumstances of the facts, since on them depended whether or not they

should submit to the heavy yoke of the law. Much less could national vanity have been the cause of attributing a supernatural character to the deeds of Moses;

for many of them are chastisements for the people's transgressions, and with almost every one is associated some trait of disloyalty, ingratitude, or sensuality,

the mention of which would rather wound than flatter their pride. Besides, not only the Israelites, but also the Egyptians, who were quite familiar with the

conditions of the country, and the Magi, so expert in all arts, like Pharao, recognized in those signs the finger of God

(Exod. 8: 19);

and the renown of these wondrous deeds penetrated even as far as Canaan (Jos. 2: 10).

(b) Moreover, it may be directly proved that in all those occurrences there are, at least, some circumstances which give evidence of their supernatural character. Thus the plagues of Egypt, by their sudden appearance and disappearance according to the prediction and at the command of Moses, by the rapidity of their succession, by their violent nature, and particularly by the fact that they spared the Israelites, display their supernatural character. It was not without cause that God chose facts which, under other circumstances, might appear natural in Egypt, since in these the Egyptians could more easily distinguish the miraculous than in less familiar occurrences. The passage of the Red Sea, as also the manna in the desert, owing to the accompanying circumstances, are manifestly supernatural.

The Seventh Plague.

It was in firm reliance on a miracle, which he had expressly predicted, that Moses led the Israelites in a southerly direction to the Red Sea, instead of going around it in an easterly course. Having at God's command, stretched forth his hand over the sea, the waters were divided, and a parching wind dried the ground, while the waters stood like a wall on their right and left. Again Moses stretched forth his hand towards the sea, and it closed over the Egyptian host (Exod. 14).

The manna, which fed the Israelites, fell with the dew from Heaven, while the sweet gum known by that name oozes from the branches of certain shrubs. The former fell for the first time when the Israelites entered the desert of Sin, accompanied them on their eastward journey, and fell for the last time on the plain of Jericho (Jos. 5: 12). The latter is to be found only in a small tract between the coast and the highest mountains. The former roused the astonishment of the Israelites; the latter has nothing remarkable about it. The former fell at night and early morning; the latter flows all day long. The former did not fall on the Sabbath, but a double quantity fell the day before; the latter flows regularly. The former fed the Israelites without intermission for the space of forty years; the latter lasts only for six weeks, during the great heat of summer. The former could be preserved only from the sixth to the seventh day, but putrefied if kept on other days; the latter may be kept for years. The former sufficed during forty years for the sustenance of nearly three million men; the latter is to be found only in small quantities, and some years not at all. Hence the fall of manna foretold by Moses was a supernatural occurrence (Exod. 16).

2. The same may be said of the prophecies. On his first appearance in Egypt Moses predicted the chastisements which were to visit the country (Exod. 3: 10; 10: 4); their termination (Exod. 8: 11); the fall of the manna (Exod. 16: 6). Neither the Israelites nor the Egyptians were so unacquainted with the quality of the soil or the climate as not to foresee ordinary occurrences, if there had been question of such. Besides, it is evident that Moses could only by divine communication know before-hand the events which depended, not on natural causes, but on God's free will. For instance, he could know only by divine inspiration that of all those over twenty years of age who had set out from Egypt, only Caleb and Josue would enter Palestine (Num. 26: 64).

II. From his first appearance at the court of Pharao till the end of the forty years in the desert, Moses appealed to these miracles and prophecies

as to evident proof of His divine mission (Exod. 7: 9). He foretold the death of Dathan and Abiron in these words: By this you shall know that the Lord hath

sent me to do all things that you see, and that I have not forged them of my own head: if these men die the common death of men, and if they be visited with a plague

wherewith others also are wont to be visited, the Lord did not send me; but if the Lord do a new thing, and the earth opening her mouth swallow them down,

and all things that belong to them, and they go down alive into Hell, you shall know that they have blasphemed the Lord

(Num. 16: 28-30).

Thus God repeatedly sealed the mission of Moses with divine approval, and thus established the supernatural character not only of the Mosaic but also of the patriarchal and the primitive revelations.

An historical book is authentic if it contains historic truth. Now, if the author of a given book is known to us, and if we have the certainty that the book has undergone no material change in the course of time, we may form an opinion of its authenticity, whether others bear witness to the trustworthiness of the author, or the work itself gives evidence of his knowledge and truthfulness. In order, therefore, to show the authenticity of the books written by Moses, we have to prove (1) their genuineness, (2) their integrity, and (3) the author's trustworthiness.

1. A book is genuine when it has for its author the person whose name it bears, or, if anonymous, when it is shown to have been written about the time to which it is attributed. Now, the genuineness of the Pentateuch (the five books written by Moses – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) rests on both external and internal grounds.

(a) The testimony of the Jewish people at the time of Christ represents Moses as the author of the Pentateuch: They have Moses and the prophets,

let them hear them

(Luke 16: 29). The early Christians, who received these books from the Jews; the pagan philosophers, who were equally hostile to Christianity

and to Judaism; the Greek and Roman writers, who refer to those writings, were convinced of their genuineness. The Jews bore the like testimony to the genuineness of these

books when, about three hundred years before Christ, they translated them into Greek; and again when (500 B.C.) after the Captivity, Esdras collected and ordered them.

The Pentateuch, as may be proved from records, existed one thousand years before Christ, at the time of the defection of the ten tribes; for the Samaritans received it

from the tribes of the kingdom of Israel. But after the separation they certainly would not have accepted from the tribe of Juda a spurious book even under the name of Moses.

Moreover, the public feasts, the popular customs, the divisions of the land – all refer to the Law, which derives its authority from the fact of its being written by Moses.

And the Israelites, doubtless, must have known the author of that code of laws which shaped their religious, moral, and social life. Thus the genuineness of the books of Moses

is clearly proved by external evidence.

(b) The author's style and tone, his familiarity with the manners and customs of the Egyptians and other nations – in short, all internal evidence likewise goes to prove the authorship of Moses. The author writes as an eye-witness, and as one who for years had lived among the people whose history he relates, as one who noted many of the occurrences just as they took place; and therefore he subsequently summarized, defined more exactly, and inculcated a second time the laws which he had already given.

2. We call a book entire or incorrupt which has not undergone any alteration in its essential parts. The essential parts of the Pentateuch are the teachings regarding faith and morals, and the record of those facts upon which the Jewish religion was based.

(a) That the Jews would not falsify their books may be inferred from the high esteem in which these were universally held. Had any falsification been attempted, it would have been chiefly in those passages which record and reprove the vices of the people; yet these are left intact to the present day. The different readings in trifling matters, which have been always scrupulously noticed, show the conscientiousness of the copyists.

(b) The Jews could not, if they would, falsify the books of the Law. The Scriptures were not only deposited in the Temple; they were also in the hands of many, and at all times there were zealots who would have detected and denounced any attempt at falsification. Nor do we find that the prophets, who so unsparingly rebuked all other crimes, ever accused priests or people of falsifying the Sacred Writings. A falsification of the books of Moses, after the separation of the ten tribes, was utterly impossible, owing to the jealousy with which the two kingdoms (Juda and Israel) regarded each other.

3. The trustworthiness of the author of the Pentateuch is proved by the strongest external and internal evidence.

(a) External evidence. The trustworthiness of a historian is beyond doubt if contemporaries and posterity unite in bearing witness to his veracity; for it would be only for the gravest objective reasons that all would unite in such testimony. Now, the contemporaries of Moses bear witness to his veracity by the fact that an entire people accepted a law, the binding force of which rested upon his authority. The people possessed the same proofs of the truthfulness of Moses as they did of his divine mission; for a messenger of God cannot but be truthful in his spoken and written statements concerning the religion he proclaims, since his words in this case are God's voice. Posterity bears witness to the truthfulness of Moses by the fact that it submitted to those laws and precepts which rest solely upon the facts recorded by him.

(b) With regard to internal evidence, Moses must have known without doubt (1) the truth of those occurrences which happened under his own eyes. Previous events, which he only briefly and incidentally mentions, could easily be handed down by tradition, considering the longevity of the patriarchs. The prudence displayed by him on many occasions, apart from the divine assistance, secured him against self-deception. (2) That he would not deceive we may conclude from the candor and sincerity which always characterized him. (3) Besides, if he would have intended to deceive, he could not; for the facts which he relates took place before the eyes of all, or were proved by miracles of which all were witness. This is particularly the case with the divine apparition in the burning bush. Moses proved to the people by many miracles that the Lord had spoken to him. As to the facts of past ages, they were equally well known to the people themselves, who certainly would have contradicted him if his narrative were untrue.

In like manner we might show the authenticity of the other sacred books of the Jews; for these also have the testimony of a whole nation in their favor; and their authors are either known to us as men worthy of credence, or must have been known as such at least to their contemporaries, who manifestly put implicit faith in their statements.

Alphabetical Index; Calendar List of Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com